China and the United States: The Evolution of a Relationship

“They are one-fourth of the world’s population. They are not a military power now but 25 years from now they will be decisive.” President Nixon thus explained why he had ordered his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, to visit Beijing in July 1971. So began the process that would open a normal diplomatic relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China.

Looking forward from 1971, Nixon sounds like a prophet. By the 1990s China’s economy was racing ahead at full steam. As the twenty-first century commenced China continued to rise. For much of this period the United States has been a beneficiary, and supporter, of China’s transformation from an isolated, agricultural country to an industrial juggernaut. Lately, doubts have arisen about whether the continued rise of China and the apparent decline of the United States will inevitably lead to conflict, or whether ties and common interests are sufficient to prevent specific conflicts of interest – such as the current tensions in the South China Sea – from erupting into actual military conflict. The short answer is: we just do not know. But the historical evolution of the past half-century may provide some solace against doomsday scenarios. For in contrast to the pre-Nixon era, Sino-American relations have, in fact, blossomed. the historical evolution of the past half-century may provide some solace against doomsday scenarios. For in contrast to the pre-Nixon era, Sino-American relations have, in fact, blossomed.

United States and “Red China”

The relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) got off to a bad start. The PRC snubbed the United States as the chief global agent of capitalism and imperialism and forged an alliance with the Soviet Union. The United States retaliated by refusing to recognise the legitimacy of the new Chinese government and continuing to uphold the Republic of China (ROC) – confined to the island of Taiwan – as the sole legitimate representative of the Chinese people, denying the PRC one of the five permanent seats at the UN Security Council until 1971. Moreover, Chinese and American soldiers killed each other in the thousands during the Korean War of the early 1950s.

While the United States stubbornly stuck to its non-recognition policy, “Red China” – as Americans preferred to call it – underwent a profound transformation. By the 1960s China was in American eyes similar – if much bigger in size – to how North Korea appears today: an economic basket case led by a strong leader, relying on a massive army, closed to the outside world, monolithic in its ideology, consumed by a deep-seated anti-Americanism, and possessing nuclear weapons (as of 1964). China was a country, as Kissinger put it, “led by a group of monks – Communist monks – who have fought for 50 years and kept their revolutionary purity.”

From Strategic Partnership to the Pivot

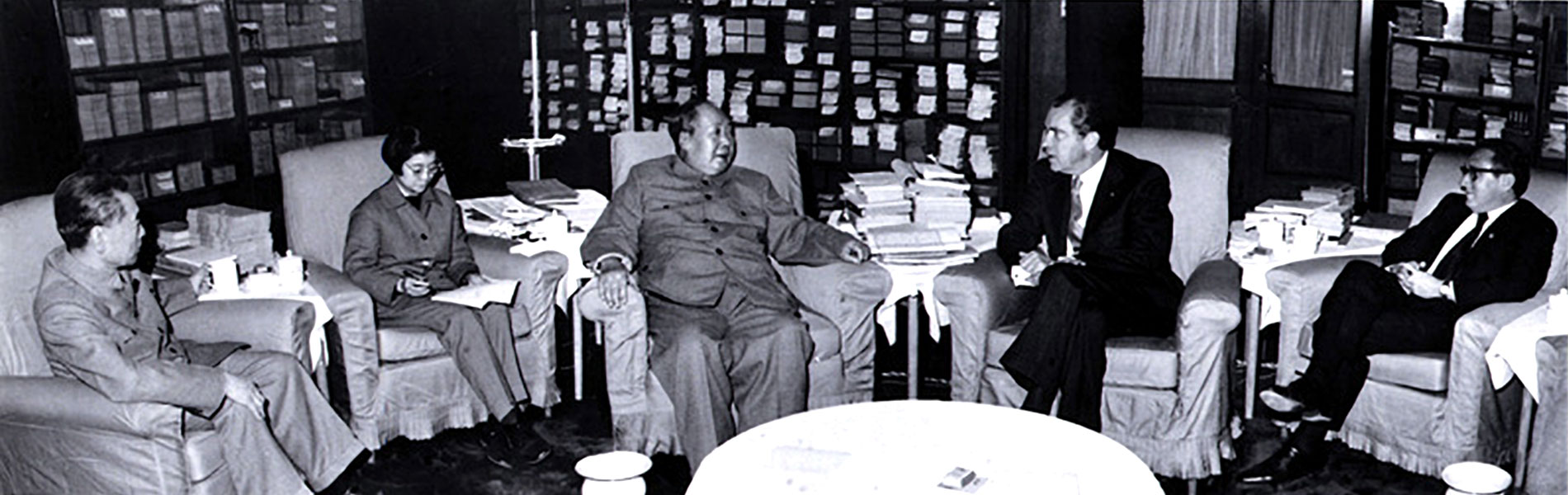

Kissinger’s secret trip to Beijing in 1971 paved the way for the biggest single transformation in US Cold War diplomacy. Nixon’s visit to China in February 1972 highlighted this initial phase of Sino-American rapprochement. Full normalisation was achieved under the Carter administration.

In fact, prior to Kissinger’s trip Beijing had established a complex web of diplomatic relations with countries around the world. In Europe, Switzerland and Sweden had been the first non-Soviet bloc countries to open relations with China in 1950. From the mid-1950s onwards China established diplomatic relations with numerous newly independent countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. In 1964, to the dismay of the United States, France and China exchanged ambassadors. In October 1970, Canada’s flamboyant Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau announced that Canada was following in France’s footsteps. The Sino-American opening may have been the most publicised of its kind – its global impact was surely the most consequential – but the United States was a latecomer to this particular diplomatic game.

The Sino-American relationship that emerged was, for the remainder of the Cold War, mainly a strategic partnership aimed at containing the Soviet Union. Sino-Soviet relations had been strained because of ideological differences and competition over influence in important strategic hotspots (e.g. Indochina). Meanwhile, the United States still saw the Soviet Union as its main adversary but in the aftermath of the disastrous Vietnam War and amidst one of its repeated moments of relative economic decline, it found its ability to use force severely restricted. Reliance on strong regional allies and diplomacy replaced military interventionism. China presented Americans an opportunity to play triangular diplomacy and undermine the Soviet Union’s influence, whereas the United States provided Beijing a degree of assurance vis-à-vis potential Soviet aggression. In practice this translated to sharing intelligence information and, as Soviet-American relations worsened in the early 1980s, to US military sales to China.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, however, weakened the rationale behind the Sino-American strategic partnership.The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, however, weakened the rationale behind the Sino-American strategic partnership. Meanwhile, between 1996 and 2015 China’s military budget grew by an annual average of 11%. Modernising the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into a force capable of projecting Chinese power in the Far Eastern region, Chinese leaders, as of 2004, have made reference to the PLA’s “new historic missions”. Many regard such statements – backed up by the world’s second most powerful military machine – with alarm and speculate on possible Chinese military takeovers of contested areas, most notably in the South China Sea.

In short, as China’s military power and assertiveness have grown, the Sino-American strategic partnership has suffered.In short, as China’s military power and assertiveness have grown, the Sino-American strategic partnership has suffered. The Obama administration has tried to reassure its long-standing allies in the region – Japan, the Philippines, South Korea among others – by militarily “pivoting” towards Asia. But little has come out of this idea, in part because the American focus has, for decades, been on other regions, most notably the Middle East. The United States has also resisted painting the Sino-American relationship as an antagonistic one, preferring diplomacy and cooperation to confrontation.

Rise and Decline in the Shadow of Globalisation

In 1971, Kissinger was certain that China’s interest in forging a relationship was “100% political”. In 1972, Sino-American trade amounted to a mere USD 4 million. However, by the late 1980s the annual value of Sino-American trade was over USD 20 billion. While American companies undoubtedly benefited, the gains were far more obvious for China, whose GDP annual growth rates averaged over 10% in the 1980s.

In the 1970s Americans still enjoyed a small trade surplus but since 1985 that balance has reversed. Already in 1989 Chinese sales to the United States were more than twice as high as US sales to China. This may not have meant much to the American economy at the time: China was the United States’ 14th largest trading partner.

Fast forward to 2016, however, and things look very different. At 15% China is America’s second largest trading partner behind Canada. At almost USD 350 billion the United States’ largest trading deficit, by a wide margin, is with China.At 15% China is America’s second largest trading partner behind Canada. At almost USD 350 billion the United States’ largest trading deficit, by a wide margin, is with China. China’s share of the world economy had grown exponentially to 13.4% by 2014 (the US share was 22.3%). And China continues to grow at 7% per year compared to the relatively anaemic 2.6% of the United States (in 2015). Consequently, a popular theme of analysts and pundits has now become America’s decline and China’s rise.

Waves of anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States have been clearly on display during the 2016 presidential election. Even as China’s growth shows signs of slowing down, the political implications of the country’s rapid transformation are huge.

The Long Shadow of Tiananmen

In June 1989, the strategic cooperation between the United States and China was further called into question when PLA tanks crushed pro-democracy demonstrations. The crackdown was a brutal reminder of the limits of China’s liberalisation and highlighted human rights as a perpetual and sensitive issue in Sino-American relations.

A few selected periods of sanctions excluded, however, the United States has not challenged China in a major way since 1989. For example, Washington firmly supported China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. In contrast to the Russian-American relationship, Sino-American economic relations have blossomed.

But what if, or more likely when, the Chinese model experiences a hiccup? What happens if the Chinese state fails to deliver improved living standards to meet its people’s continuously rising expectations? The lack of political rights is a potentially toxic element that may well undermine China’s continued “rise” by calling into question the legitimacy of its political system. Unlikely? Perhaps. Impossible? Hardly. The lack of political rights is a potentially toxic element that may well undermine China’s continued “rise” by calling into question the legitimacy of its political system. Unlikely? Perhaps. Impossible? Hardly.

Too Big to Fail?

The evolution of Sino-American relations over the past 50 years or so is a tale of successes and paradoxes. In the 1970s the two countries entered into a strategic partnership to contain the Soviet Union. As of the 1980s the relationship has gradually morphed into a rapidly growing economic interdependence. Today, the relationship between China and the United States is, undoubtedly, the most important bilateral relationship on the globe. But, much as in Nixon’s day, it is also a relationship that is filled with issues on which the two countries agree to disagree. Respect for human rights is but one thorny problem that Beijing and Washington are unlikely, under the present situation, to discuss seriously.

Nothing lasts forever. A change in the pattern of Sino-American relations could arise from two sources. Although unlikely, it is possible that military action involving US allies in the South China Sea could prompt the United States to enact severe measures vis-à-vis China. These would probably not remain unchallenged. An action-reaction cycle might result in potentially catastrophic consequences.

A more likely “game-changer” would emerge as a consequence of domestic pressures on both sides. An anti-globalisation/neo-isolationist shift in the United States could prompt policies aimed at clamping down on China’s “unfair” trade policies by raising tariff barriers against Chinese products. Such policies would find support among human rights advocates willing to press China towards political reform. In China, an economic downturn could stroke the flames of nationalism and place the many historical grievances – real and invented ones – to the forefront of the government’s effort to shift attention from domestic problems to foreign threats.

In conclusion, today, there is little to indicate that either scenario is probable, let alone inevitable. More likely is the continuation of competitive coexistence between the world’s two largest economies that have little to gain from direct conflict with each other.

US TRADE IN GOODS WITH CHINA, 1992–2015 (IN USD MILLION)

Source: US Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with China”.

South China Sea: Elementary Data

East Asia

3.5 million km²

Brunei, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam.

Petroleum, natural gas and fisheries products.

Each year, USD 5.3 trillion of trade passes through the South China Sea; US trade accounts for USD 1.2 trillion of this total.

The South China Sea contains over 250 small islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs and sandbars, most of which have no indigenous people, many of which are naturally under water at high tide, and some of which are permanently submerged.

Source: by Galvin and whybe.ch.

The Disputed Islands

The Spratly Islands are a disputed group of 14 islands, islets and cays and more than 100 reefs, sometimes grouped in submerged old atolls. The archipelago lies off the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia and southern Vietnam. The islands have no indigenous inhabitants, but offer rich fishing grounds and may contain significant oil and natural gas reserves. Some of the islands have civilian settlements, but of the approximately 45 islands, cays, reefs and shoals that are occupied, all contain structures that are occupied by military forces from Malaysia, Taiwan, China, the Philippines and Vietnam. Additionally, Brunei has claimed an exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

The Paracel Islands are a group of islands, reefs, banks and other maritime features. They are controlled (and occupied) by China, and also claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam. The archipelago is surrounded by productive fishing grounds and a seabed with potential, but as yet unexplored, oil and gas reserves.

Scarborough Shoal is a disputed territory claimed by China, Taiwan and the Philippines. Since the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, access to the shoal has been restricted by China. Scarborough Shoal forms a triangle-shaped chain of reefs and rocks with a perimeter of 46 km. It covers an area, including an inner lagoon, of 150 km2. The shoal’s highest point, South Rock, measures 1.8 m above water during high tide.

The Pratas Islands are an atoll in the north of the South China Sea consisting of three islets about 340 km southeast of Hong Kong. Excluding their associated EEZ and territorial waters, the islets comprise about 240 ha, including 64 ha of lagoon area. China claims the islands, but Taiwan controls them and has declared them a national park. The main island of the group, Pratas Island, is the largest of the South China Sea islands.

Macclesfield Bank is an elongated sunken atoll of underwater reefs and shoals. It lies east of the Paracel Islands, southwest of the Pratas Islands and north of the Spratly Islands. Its length exceeds 130 km southwest-northeast, with a maximal width of more than 70 km. With an ocean area of 6,448 km2 within the outer rim of the reef, although completely submerged without any emergent cays or islets, it is one of the largest atolls of the world. Macclesfield Bank is claimed, in whole or in part, by China and Taiwan.