Diplomatic Gambling versus New Diplomacy

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-x84k-dv11Post–Cold War diplomacy has been a diplomacy oriented toward globalisation through the expansion of multilateralism to new issues, and the extension of international cooperation to new actors and states. However, the recent questioning of globalisation and growing military tensions have seriously undermined multilateral diplomacy. What we call a “speculative” approach to diplomacy — transactional, disruptive, aggressive, and serving the sole interests of particular corporate interests — clashes with the multilateral and multistakeholder paradigm that became prevalent after the Fall of the Berlin Wall. In many ways, this form of diplomatic gambling extends to the world of diplomacy the kind of speculative behaviour related to the age of “casino capitalism”. It differentiates the kind of realist approach to diplomacy adopted by various great powers like Putin’s Russia from Trump’s United States, which is pursuing a more outright confrontational course with other powers in Europe, Asia and Africa based on such a speculative approach to power politics.

Diplomacy as an age-old trade

For a long time, the classic idea put forward by Martin Wight that the diplomatic system is the central institution of international relations, and diplomacy the art necessary for the stabilisation of relations between states, was taken for granted. From such a perspective, the mission of diplomacy is to ease tensions between states through tactful politics of experienced men learned in the same game of international politics, who engage in the long-term courting of allies, while seeking to balance national state interests and collective responsibilities.

Historically, while diplomatic relations have existed since Antiquity (see timetable), the conduct of diplomatic relations between states through official missions was institutionalised only in the 17th century, after the first permanent delegations were established, at least as far as Europe was concerned, during the Renaissance. This “traditional diplomacy” or “old diplomacy” which emerged in Europe, as reflected in the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, recognised the equal status of all sovereign states — insofar as they recognised the primacy of Christendom and its institutions — and was characterised by the central role of embassies, a formal code of conduct between European states, and a high degree of secrecy in negotiations.

In that realist world of diplomacy, multilateral institutions such as the League of Nations, the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) served a useful purpose: they were conceived as alliances of like-minded states, who gathered to consolidate their alliance around common institutions, in charge of preparing the alliance against the revival of a common threat, represented by a common enemy. Whether the latter was a defeated German Empire (as in the case of the League of Nations), or the Third Reich and the Axis powers (as in the case of the United Nations), or the Soviet Union (as in the case of NATO), all member-states sent professionally trained diplomats to these institutions to help them coordinate their state interests against one common state enemy.

While multilateral diplomacy thus has long-standing roots, its association with democratic values, limitations on the number and type of weapons to be deployed in war, and a new ethos of democratic accountability in multistakeholder negotiations may be dated back to Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the creation of the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919. The interwar era is often remembered as the failure of a collective security arrangement that was unable to prevent war in Europe or the Holocaust, but many historians have debunked the idea that there was no continuity between the League and the UN institutional architecture sustaining universal values such as the respect for human rights or gender equality. In fact, the creation of the UN eventually gave rise to more than 50 international organisations that expanded the scope of topics to be addressed through multilateral discussion and international cooperation well beyond the formation of common security pacts, and to do so, it heavily drew on organisations already established during the interwar era in Paris, Rome and, indeed, Geneva.

Of course, throughout the Cold War, the most prominent issues related to war and peace were often settled through bilateral deals following world crises between the two hegemons, which had veto power in the UN Security Council — from the Korean War to the Berlin crises and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Still, even nuclear diplomacy involved the creation of a tapestry of overlapping and complex regional rules that tied the two major nuclear powers to some form of rules-based multilateral orders, one of which was central to the creation of the EU. It was the end of the Cold War that promised a world where multilateral regionalisms would be harmonised within a truly global world system of rules, as illustrated by the transformation of the GATT into the WTO, and where the notion that a multilateral organisation should function like an institutionalised alliance against a common enemy began to fade.

The Professionalisation of New Diplomatic Elites

Still, this narrative, although not historically wrong, remains at the institutional level and does not capture the sociological changes at work in the world of diplomacy since the 1960s, which preceded the end of the Cold War and also participated in uncoupling the world of multilateralism from the notion of a security pact. From the 1960s onward, the period also saw a sea change in the actors of diplomacy, following efforts to diversify recruitment in many countries, particularly by opening up entrance examinations and recruiting new diplomatic elites in newly independent states that understood the world of diplomacy primarily through their participation in multilateral fora like the African Union or the UN. In the context of decolonisation and North-South cooperation during the Cold War, the competition to train diplomats for the newly independent countries was in full swing and two conventions organising the rules of modern diplomacy were signed in Vienna: the 1961 Convention on Diplomatic Relations and the 1963 Convention on Consular Relations. The Geneva Graduate Institute played no small role in that endeavour to professionalise the art of diplomacy and strongly anchor it in the UN multilateral system of values.

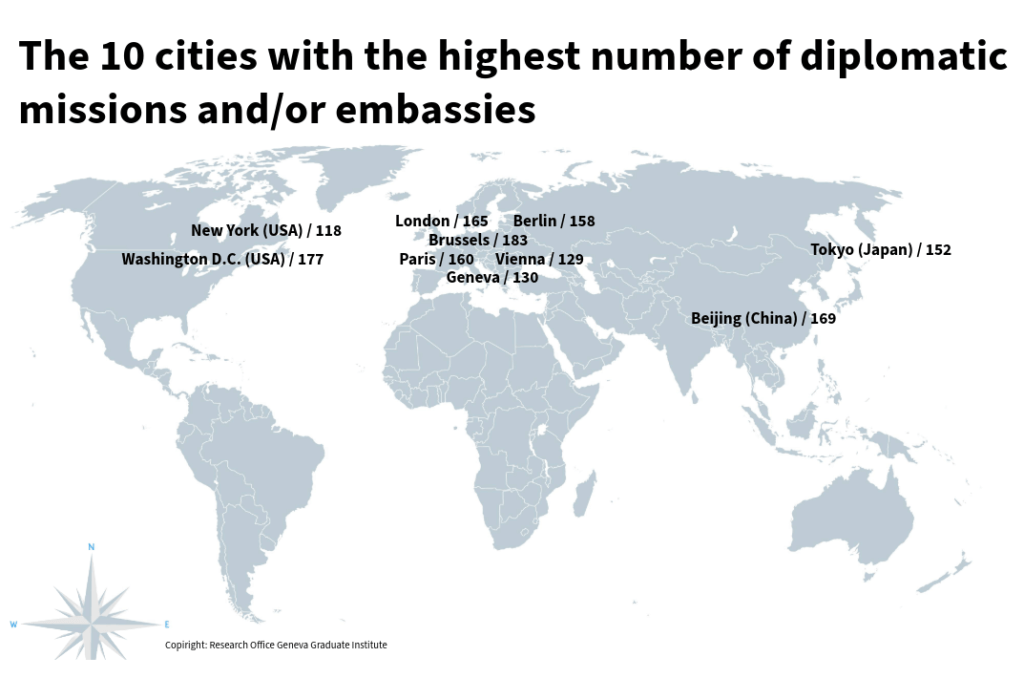

Extrapolating from data of the Lowy Institute — which has been providing a global snapshot of state diplomacy through its Global Diplomacy Index since 2016 —, there are around 50,000 diplomats in the world today, whether they are posted to foreign ministries, embassies in national capitals or the headquarters of international organisations in New York (UN headquarters), Geneva (headquarters of numerous UN agencies), Brussels (headquarters of the European Union) and Washington DC (capital of the United States).

The 66 most diplomatically active countries count an average of 120 representations abroad. The United States and China top the list, while many European cities rank in the top 10 positions. India and Turkey have opened most new embassies over the past two years, reflecting their increased ambitions on the world stage, while other ascending powers such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia are positioning themselves as alternative hubs for global negotiations.

The multistakeholder paradigm

While traditional realist diplomacy prioritised the management of territorial, military or political conflicts, which it clearly distinguished from the defence of rule of law, democracy and human rights — relegated to domestic issues —, multilateral diplomacy after the end of the Cold War increasingly had to deal with interconnected global issues such as climate change, global health (e.g. COVID-19), human rights, migratory flows and humanitarian crises, in which no state had a common enemy, but all participated in finding solutions to collective problems.

At the turn of the 21st century, multilateral diplomacy became more open to new actors, and new collaborative and multistakeholder approaches gradually complemented, challenged or, at times, superseded traditional bilateral diplomacy diplomacy and/or multilateral diplomacy conceived as a collective security pact. In many ways, diplomacy ceased to be the sole prerogative of the states and their chancelleries, now frequently including civil servants from other ministries (economy, culture) and civil society representatives (NGOs, cities, trade unions, companies), and new types of partnerships (e.g. public-private) emerged. While bilateral diplomacy did not lose its importance during that period, it became increasingly entangled with multilateral diplomacy or what is often called “multilevel diplomacy” or “transnational governance”, which is characterised by the creation of a wide range of frequently informal networks and alliances and a high level of permeability to the corporate sector.

Driven by digital innovation and the demands for greater public accountability, the democratisation of such transnational forms of governance has sometimes been associated with corporate capture of public negotiations, but it has led to greater inclusiveness, transparency and openness in diplomacy. Concurrently, diplomats have learnt to engage with larger audiences — including those abroad — and to mobilise them in their own interests. The growing importance of Southern actors has further contributed to broaden the thematic and geographic coverage of diplomatic affairs. As an increased number of actors partake in the negotiations of global standards and policies, diplomacy has moved from the hushed salons of embassies and grand hotels to the convention rooms of international congregations such as Conferences of the Parties (COP), privately organised events such as the WEF or highly publicised summits such as the G7 or G20 with their cohorts of experts and “sherpas”.

Multilateral diplomacy in the ropes

The current multilateral order, however, is wavering. It has long been facing criticism by a wide range of actors, notably from the Global South, for being Eurocentric, unjust and neo-imperial. Today, the diversion of the collective interest in favour of state interests, underpinned by a global rise of authoritarianism, is leading to the “rolling back of multilateralism” and to increased tensions, fragmentation, and uncertainty in the international system. Such strategic selfishness is illustrated by the behaviour of old powers (for instance, the European powers still generally hold the presidency of the IMF while the US keeps that of the World Bank), but also by that of new major powers, such as China, which equally seeks to control key positions in international organisations or to substitute them with its own creations.

Other great powers tend to view the new understanding of multilateral diplomacy that emerged since the end of the Cold War with suspicion. When it can, Russia bluntly abuses mechanisms such as the Security Council to further its expansionist schemes and block any decision condemning its acts of aggression. To justify its action, Putin’s Russia criticises the idea that multilateral institutions (especially NATO) no longer serve as collective security pacts against a common enemy (Russia, in this case) and that they serve the interests of all states in the 21st century (for example by fighting transnational terrorist organisations, as NATO was supposed to do after 9/11 when it invaded Afghanistan).International affairs are witnessing the rise of a more aggressive style of diplomacy For Putin, the Cold War has not ended; it has just morphed into a new shape. The United States, for its part, openly seek to weaken organisations that do not defend its interests, for instance by delaying the appointment of judges to the WTO Dispute Settlement Body or by suspending its financial support to the World Health Organization, which it criticizes for being captured by Chinese views.

The potential for shared common understanding of how bilateral and multilateral diplomacy could help solve common problems thus seems to be dwindling, as international affairs are witnessing the rise of a more aggressive style of diplomacy upholding the sacrosanctity of state sovereignty and relegating all questions related to human rights, humanitarian law, gender equality and antiracism to issues that are, at best, a matter of domestic choice and, at worst, “ideologies” to be countered through transnational campaigns in favour of “traditional family” values and anti-immigration rhetoric.As polarisation is growing and hegemonic strategies to spread counter-Enlightenment discourses are taking the front of the scene, the multilateral order of the early 21st century seems to be disintegrating at the very moment when there is an unprecedented need for common solutions.<br /> As polarisation is growing and hegemonic strategies to spread counter-Enlightenment discourses are taking the front of the scene, the multilateral order of the early 21st century seems to be disintegrating at the very moment when there is an unprecedented need for common solutions to pressing transnational issues. The challenge for the future of world diplomacy therefore lies in the reinvention of multilateralism, as the normative apparatus underpinning international cooperation has lost its traction and the US, its historical cornerstone, are no longer upholding it.

Speculative Diplomacy in Mar al Lago

Trump’s return to the White House has further aggravated this crisis. Recklessly promoting certain “American” corporate interests over the sanctity of territorial state boundaries of its enemies and allies alike (even threatening territorial expansion through force in the case of Greenland or Canada), Trump’s diplomatic style constitutes a novel type, which, we claim, has little to do with Putin’s realist diplomacy, but which translates into the diplomatic field some practices coming from the world of gambling and speculation, thus disconcerting many commentators.

Trump’s diplomatic style constitutes a novel type, which, we claim, has little to do with Putin’s realist diplomacy, but which translates into the diplomatic field some practices coming from the world of gambling and speculation. The new style of US diplomacy is based on transactional relations of opportunity and targeted trade wars and is radically calling into question multilateral collaboration, including in traditional security fields, by blurring the line between enemy and friend (the sacrosanct boundary of all realist discourse). As President Trump repeatedly stated, allies are only allies to the extent they pay what the US President believe they owe financially to US military corporate interests: all allies and enemies are targets of suspicion, and possible extorsion for more financial resources. Trumps’ exorbitant tariffs are a case in point, as they seem designed less to implement a protectionist grand scheme than to maximise bargaining clout to make gains on other fronts. It is a highly risky gambling strategy, played like a poker game, when realists advise building alliances to contain enemies, as Go players do.

Some have also described Trump’s approach to diplomacy as “deal-omacy”, in reference to his book Trump: The Art of the Deal. Curiously, this diplomacy of the one-time deal and its penchant for risky transactions and gambling have been little theorised. Analysts have stressed the prevalence of economic interests and objectives in Trump’s foreign policy as well as the strong personalisation of his negotiation practices, which may be anchored in the real estate business, where he made a long career before turning to politics and, indeed, diplomacy. Conducting diplomacy like a private business, multiplying one-shot transactions (as happens when one sells a building or flat, in contrast to the diplomatic game of repeated transactions), Trump’s administration constantly mingles national with private interests, ultimately betraying a oligarchic agenda serving the corporate elites that support it. This manner of conducting foreign policy is quite foreign to the “realist” tradition, which emphasises the importance of lasting relations, to be constructed over successive rounds of transactions by professionals well versed in the art of identifying state (not corporate) interests.

At last, President Trump’s diplomacy is characterised by an obsession of the instantaneous and public character of its actions (as reflected in his tweet-diplomacy), a dramatic shrinking of the decision-making horizon and a chronic short-sightedness that prevents any long-term planning. The dismantling of USAID, to be followed by an equally strong attack on diplomatic professionals, as announced by budget cuts at the State Department as well as in Ivy League schools and universities (Harvard, Princeton, etc.) where diplomatic professionals are traditionally trained, is antithetical to the realist creed in professionalism and vocational secrecy. If Trump’s diplomacy may have the appearance of the classical realist tenet, with its focus on power and national corporate interests, as embodied by Putin’s diplomacy, it thus deviates from realism in important ways. His love for prominent and public unilateral declarations through social media and a confrontational tit-for-tat approach depart from the secret diplomacy favoured by realists.

Trump’s disruptive diplomatic hyper-realism goes beyond the classic realist doctrine, displaying, in many ways, unconventional or even outright eccentric characteristics. It may be construed as an original blend of deal-making, bullying and showmanship, or what has also been described as “megaphone” or “circus” diplomacy. Trump’s diplomacy is further marked by an extreme versatility, the absence of any pretension to rationality and the total disrespect for rules, conventions and protocols, as illustrated by his surreal humiliation of Zelenskyy on 28 February 2025 during a diplomatic meeting set up as a mock-reality TV show.

Towards a “new” diplomacy?

Thus, the turmoil accompanying the current change in the geopolitical landscape seems to be restoring the visibility of state diplomacy on the surface, but it may in fact weaken the professionalised diplomacy of the postcolonisation era. Paradoxically, however, the looming collapse of the multilateral order could serve as a catalyst for the revival of a broader coalition defending a new diplomacy aspiring to a revamped, more progressive approach to multilateralism. The diplomacy of tomorrow could increasingly be characterised by fragmentation, instability and the prevalence of “hybrid”, “ad hoc”, corporate-driven approaches to agenda-setting that are purely speculative in the sense that they seek private short-term gains. Paradoxically, however, the looming collapse of the multilateral order could serve as a catalyst for the revival of a broader coalition defending a new diplomacy aspiring to a revamped, more progressive approach to multilateralism.

Many actors are indeed calling for a new diplomacy that would be more inclusive, interconnected, professional and tech-savvy, involving a multitude of actors and experts as well as the private sector — provided that the latter agrees to serve the collective interest by participating in the identification of solutions that states or other public actors (cities, etc.) cannot reach alone. Such a new diplomacy would also integrate the perspectives and contributions of marginalised groups, including women, racialised minorities, young people and local communities, in stark contrast with the oligarchic and masculinist approach of many autocratic leaders who are in power today. Inter-state dialogue, international cooperation between various levels of governance (from city councils to supranational organisations) and the participation of civil societies, indeed, seem more necessary than ever to deal with today’s complex global challenges, and professionalised diplomacy remains the principal substitute to the use of force to deal with problems.

Beyond a holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world, this new diplomacy aspires to a response that is commensurate with the gravity of the crisis facing multilateralism. In the words of Peter Maurer and Mohamed Mahmoud Mohamedou, diplomacy should be a multi-level “integrator of international interaction” between expertise, science, technology and civic action, and ultimately constitute a “fluid and plural activity”.

-

1

Diplomacy in International Geneva: Beyond Business as Usual

Diplomacy in International Geneva: Beyond Business as UsualScepticism about the scope for international cooperation is a reality of today’s geopolitical environment. For Marie-Laure Salles and Achim Wennmann, this difficult climate nonetheless offers a window of opportunity: if negotiators can move beyond the zero-sum game, it could be the moment for a new, more fluid diplomacy where diplomats act as “policy entrepreneurs”, building alliances and negotiating innovative solutions to key global issues.

-

2

The Modern Diplomat: Exposed, Endangered and Indispensable

The Modern Diplomat: Exposed, Endangered and IndispensableIn a world of 24-hour news cycles, diplomats must react quickly to the latest political developments, often communicating directly with the global public via social media. In this 21st century context, writes Jussi Hanhimäki, the most significant change to diplomacy is that the diplomat’s role — for better or for worse — has become much more transparent than it was in the past.

-

3

The New Trade of Trade Diplomacy: What Role for Trade Negotiators in a Trade World on Fire?

The New Trade of Trade Diplomacy: What Role for Trade Negotiators in a Trade World on Fire?In a context where the US President can declare tariffs “the most beautiful word in the dictionary”, trade negotiators have their work cut out for them. Examining the job of a trade negotiator today, Joost Pauwelyn situates present-day trade negotiations in a world where global trade is often weaponised and where multilateral negotiations are increasingly losing ground to bilateral posturing.

-

4

Diplomacy and Decolonisation

Diplomacy and DecolonisationDecolonisation was not a straightforward affair as colonial powers used every political, military, and diplomatic trick to keep former colonies under their thumb. Yet newly independent countries were quick to shake up the diplomatic stage. How did this come about? Gopalan Balachandran explains.

-

5

Rethinking United Nations Mediation

Rethinking United Nations MediationThe UN’s mediation efforts are challenged by geopolitical deadlock within the Security Council and state mediators prioritising short-term deal-making over peace-making. Sara Hellmüller explores how the UN can retain its relevance in addressing armed conflicts by bridging divisions within the Security Council, fostering coalitions among elected members, and adapting its mediation role to complement other peace efforts while upholding its core principles of inclusive, sustainable conflict resolution.

-

6

Diplomatic Relations, Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Threats

Diplomatic Relations, Artificial Intelligence and Cyber ThreatsToday’s diplomats frequently post on social media, shaping the discourse on key foreign policy issues in real time. Analysing the prevalence of emerging technologies, including AI, and the importance of cooperation with big tech companies, Daryna Abbakumova surveys the rapidly changing technological environment in which diplomats are now required to operate.

-

7

The G7: From Global Governance to Geoeconomics

The G7: From Global Governance to GeoeconomicsWhen created in the 1970s, the G7 intended to foster closer transatlantic ties by facilitating economic cooperation and reaffirming Western unity. Tracing the G7’s historical evolution, Mattia Ravano situates this informal forum in today’s geopolitical context and investigates the particular challenges faced by an informal diplomatic arrangement of this kind.

-

8

Women’s Organisations of Diplomats: A New Era for Diplomacy?

Women’s Organisations of Diplomats: A New Era for Diplomacy?As increasing numbers of women have taken on the role of representing the state, a number of informal collectives have been set up around the world to mobilise for gender equality in diplomacy. Amena Martins Yassine examines the development of these women’s organisations of diplomats, and their potential to change the way diplomats operate.

-

9

Evolving Paradigms in Science and Tech Diplomacy

Evolving Paradigms in Science and Tech DiplomacyIn today’s fractured world, science is no longer confined to laboratories. From pandemics to climate change and AI, Stéphanie Balme shows that researchers, diplomats, and tech giants now play central roles in international relations. As global challenges grow more complex, science and technology diplomacy emerges as a key tool for cooperation — and confrontation.

-

10

The Geneva Graduate Institute and the Training of Diplomats in the Context of Decolonisation

The Geneva Graduate Institute and the Training of Diplomats in the Context of DecolonisationAs the US and the Soviet Union competed during the Cold War to recruit students from newly independent countries, so, too, did Switzerland seek to attract such students to its universities. Surveying the historical role of Switzerland in educating future leaders from the Global South, Charlotte Roy and Nicolas Hafner investigate the diplomatic potential of further education during the Cold War years.

-

O

Publications of the Geneva Graduate Institute in the Field of Diplomacy

Publications of the Geneva Graduate Institute in the Field of DiplomacyThis selection of resources aims to complement the articles above.

Electronic reference

Mallard, Grégoire, Dominic Eggel, and Marc Galvin. “Diplomatic Gambling versus New Diplomacy.” Global Challenges, no. 17, May 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/17/diplomatic-gambling-versus-new-diplomacy. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-x84k-dv11.Dossier produced by the Research Office of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

TABLE | The 20 Countries with the Most Diplomatic Missions in the World in 2024

| Country | Total number of posts | Embassies | Consulates | Permanent Missions | Other representations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 274 | 173 | 91 | 8 | 2 |

| USA | 271 | 168 | 83 | 11 | 8 |

| Turkey | 252 | 145 | 93 | 12 | 2 |

| Japan | 251 | 152 | 66 | 10 | 23 |

| France | 249 | 158 | 72 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | 230 | 143 | 74 | 10 | 3 |

| UK | 225 | 156 | 51 | 11 | 7 |

| Germany | 217 | 148 | 56 | 11 | 2 |

| Italy | 206 | 124 | 74 | 8 | 0 |

| Brazil | 205 | 135 | 58 | 12 | 2 |

| India | 201 | 142 | 50 | 5 | 4 |

| Spain | 190 | 114 | 65 | 10 | 1 |

| South Korea | 187 | 114 | 60 | 5 | 8 |

| Mexico | 161 | 80 | 71 | 8 | 2 |

| Canada | 157 | 98 | 38 | 11 | 10 |

| Argentina | 150 | 87 | 54 | 7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 149 | 106 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| Switzerland | 141 | 102 | 30 | 7 | 2 |

| Hungry | 140 | 87 | 43 | 7 | 3 |

| Poland | 135 | 91 | 33 | 9 | 2 |

All data taken from the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index 2024.

BOX 1 | Diplomatic Realism

Diplomatic realism, often simply referred to as realism, is a theory of international relations that emphasises the competitive and conflictual nature of relations between States. Here are some key principles of diplomatic realism:

- International anarchy: The international system is anarchic, meaning that there is no higher authority to regulate relations between States. States must therefore rely on their own means to ensure their security and interests.

- State sovereignty: States are the main actors in international relations. They are sovereign and act rationally to maximise their security and power.

- Power and national Interests: States seek to maximise their relative power in relation to other states. Power can be measured in terms of capabilities — military, economic, technological, etc. National interests, often defined in terms of security, survival and prosperity, guide the actions of States.

- Balance of power: States form alliances and adopt strategies to maintain a balance of power, thus preventing a single State or coalition of States from becoming too powerful and threatening their security.

- Inevitable conflict: Realists consider conflict to be an inevitable feature of international relations. States are in constant competition for resources, territory and influence, which can lead to conflict and war.

- Pessimism about cooperation: Realists are sceptical about the possibility of lasting international cooperation. They see international institutions and agreements as tools that States use to promote their national interests rather than as means of genuine cooperation.

Diplomatic realism has been influenced by thinkers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and more recently by modern theorists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. This theory provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of States in a world where security and survival are of paramount concern. This realist theory is one of the analytical frameworks for international relations, in addition to liberalism and constructivism. They all have in common that they are rooted in Western philosophy.

Source: David Ho, “Les théories chinoises des relations internationales: une brève introduction”, La Revue d’histoire militaire, 4 April 2024.

BOX 2 | The New Diplomacy

“New diplomacy” refers to an evolution in traditional diplomatic practices, marked by the emergence of new actors, new means of communication and new issues. It is a concept that has emerged in response to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, marked by globalisation and the growing interdependence of states. It contrasts with traditional diplomacy, which is state-based, secret and bilateral, embodied by foreign ministries and embassies.

- Expansion of diplomatic actors: While traditional diplomacy was monopolised by states, new diplomacy involves multiple actors. It includes non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies, local authorities (cities, regions), international organisations (UN, WTO, EU…), citizens and social movements.

- Transformation of tools and channels: Digital tools have profoundly changed diplomatic practices. Public diplomacy and “twiplomacy” (diplomacy via X and other networks) enable direct communication between diplomats and the public.

- Broadening of themes: The new diplomacy addresses complex global issues such as climate change, global health, human rights, migration, digital governance and gender equality. For instance, the climate negotiations at COP26 involved not only states, but also NGOs, businesses, indigenous peoples and young activists such as Greta Thunberg.

- Collaborative and multi-level approaches: Diplomacy is no longer just vertical (between governments), but also horizontal, via cooperation networks between cities (e.g. C40 Cities), universities and civil society.

- More transparent and responsive diplomacy. Negotiations are increasingly subject to pressure from public opinion, the media and real-time communication dynamics. This makes diplomacy more visible, but also more vulnerable to polarisation or communication effects.

In summary, new diplomacy is a more holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world. It seeks to address global challenges through cooperation, engagement with a diversity of actors, and the use of new tools and technologies.

BOX 3 | Figures on International Geneva and Impact of US Cuts on United Nations Funding

- 43 international organisations in the Lake Geneva area (38 in Geneva, 46 in total in Switzerland)

- 183 States represented

- About 750 non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- More than 4,000 visits per year of heads of state and government, ministers and other dignitaries

- In 2024, 36,460 people were employed in IOs, NGOs and permanent missions:

- 28,962 people employed in IOs

- 4,062 people employed in permanent missions

- 3,436 people employed in NGOs

- In 2024, the United States funded 22% of the UN regular budget, more than China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). But in 2025, it significantly reduced its financial contributions:

- Reduction of more than 80% for the UN regular budget, affecting more than 40 international organisations, including UNESCO and the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Suspension of USD 377 million for UNFPA, the UN agency for reproductive health, impacting 48 programmes in crisis areas such as Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine

- Cuts of USD 160 million for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), jeopardising global efforts to monitor avian influenza

- Estimated reduction of 30% for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), affecting more than 6,000 employees worldwide.

- To prevent staff layoffs due to the US funding freeze, the Canton of Geneva has allocated CHF 10 million and the City of Geneva CHF 2 million to support local NGOs.

Sources: République et canton de Genève, “Statistiques cantonales”. République et canton de Genève, Genève internationale, “Facts and Figures”. Confédération suisse, “Facts and Figures about International Geneva”. Better World Campaign, “Proposed FY25 Spending Bill for Foreign Operations Would Gut U.S. Global Standing”, 6 April 2025. United Nations Office at Geneva, “US Funding Cuts Confirmed, Ending Lifesaving Support for Women and Girls”, 27 February 2025. Susannah Savage and Michael Peel, “American Farmers Raise Alarm As US Cuts Funds for UN Bird Flu Fight”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025. International Organization for Migration, “Update on IOM Operations amid Budget Cuts ”, 18 March 2025. US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, United Nations Issues: US Funding to the UN System, by Luisa Blanchfield, IF10354, 9 April 2024. Frédéric Julliard, “Genève souffle le chaud et le froid sur les ONG”, Le Temps, 17 February 2025. Fanny Scuderi, “La ville de Genève alloue 2 millions de francs d’aide aux ONG”, 13 March 2025.

VIDEO | Former US Representative to the UN Amb. Sheba Crocker on Her Three Years in International Geneva

U.S. Mission Geneva

VIDEO | Diplomacy Today, with Stephan Klement, EU Diplomat and Special Adviser on Iran Nuclear Issue

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | La diplomatie de la restitution des œuvres d’art avec Amb. Angelo Dan

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute