Diplomatic Relations, Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Threats

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-193x-nx93Diplomatic relations in the 21st century are very different from those in the 17th century, when diplomacy in its modern form began to emerge. Back then, envoys of kings and queens travelled the world to deliver important documents or convey important news to the ruler of another state, at the same time discussing the relationship between the two countries. Nowadays, heads of state do not even need to leave their office to convey their thoughts or intentions — this can be done through a speech to the media or a single post on social media. And the whole world will immediately know the intentions of a particular state in its foreign policy. A striking example is Twitter diplomacy, or “Twiplomacy”, which was particularly popular and widespread before Twitter became known as X and diplomats faced a difficult dilemma of whether or not to continue their presence there.

Nevertheless, diplomatic relations have not lost their relevance today, it is only their form that has changed and improved. Although many professions are beginning to disappear due to the emergence of artificial intelligence, displacing people from the labour market, AI is unlikely to significantly affect diplomats. They are still important intermediaries in relations between states.

At the same time, the development of new technologies has brought changes to the way diplomatic missions operate and the issues they deal with. The Vienna Conventions of 1961 and 1963 regulate diplomatic and consular relations exclusively between states. At the time of their adoption, no one thought that new diplomatic actors such as the European Union (EU) would come to play such a dominant role or that diplomatic representatives would be assigned to technology companies in Silicon Valley. But times are changing rapidly and what used to seem unreal has now become a reality, such as the introduction of the position of a Tech Ambassador in Denmark or the positions of Cyber Ambassadors in Australia, Estonia, the USA and other countries. Even the EU has recently opened an office in Silicon Valley to have access to large technology companies. The United Nations (UN) has also not been left behind and introduced the position of the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology in 2022 and, from 1 January 2025, the UN Office for Digital and Emerging Technologies.

Many states consider it necessary to conduct a direct dialogue with large technology corporations such as Google, Microsoft, Meta, Apple and many others. And this is not surprising, because more and more power, money and information are concentrated in the hands of these corporations. The legendary phrase of the British banker Nathan Mayer Rothschild “He who owns the information, owns the world” seems very relevant today, as these companies store an incredibly large amount of information on their servers. States are establishing ties with big tech companies in the Silicon Valley, because their influence has already gone far beyond that of ordinary private companies. In fact, cooperation with technology companies has become a separate area of activity for foreign affairs ministries and, accordingly, a vector of diplomatic relations.

The activities of diplomatic institutions themselves are also being influenced by new technologies, especially artificial intelligence. For example, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced a few years ago that it would use artificial intelligence to improve its work on analysing and making diplomatic decisions. And, oddly enough, it was the Chinese company DeepSeek that made a lot of noise in January 2025 when it released the first reasoning model that can not only give direct answers to questions but can also “think”, generating a “chain of thought” before delivering the answer to a query and argue its decision. Now OpenAI with its ChatGPT has a competitor in another part of the world.

Today, many states are trying to develop their own AI-based tools for optimising the work of their diplomatic missions and modelling certain international situations.Today, many states are trying to develop their own AI-based tools for optimising the work of their diplomatic missions Of course, AI cannot make decisions instead of diplomats: we all know that AI makes a lot of mistakes and generates inaccuracies, and that we shouldn’t rely on AI alone to solve problems of global importance. Foreign ministries, too, are well aware of this and that diplomats should carefully check all data generated by AI before making a final decision. At the same time, AI is a powerful new tool in the sense that it can create new opportunities for diplomacy: analysing large amounts of information in a short period of time, creating reports or summaries of meetings, and performing other routine paper-based diplomatic tasks.

A striking example of AI being used by diplomatic and consular institutions is the visa issuance process. In recent years, this process has become so automated that it allows consular officers to save significant time previously spent analysing thousands of applications and thus to focus on more important issues. AI is already actively used by the Schengen countries to control European borders, not only for biometric data processing but also for emotion recognition and risk assessment. It allows not only for exchanging information between the visa systems of member states but also for joint approaches to solving common problems.

While using the latest technologies, diplomats should not forget about the growing number of cyber threats. Cyberattacks on state bodies, including diplomatic and consular missions, have already become commonplace and, unfortunately, their number will only increase.Cyberattacks on state bodies, including diplomatic and consular missions, have already become commonplace In this situation of constant technological challenges, states should pay special attention to hiring IT specialists who will not only deploy AI and monitor cybersecurity, but also help diplomats understand the new technologies and the nuances of their application. This is now a necessity that will strengthen a state’s position both in the international arena and in its diplomatic relations.

Electronic reference

Abbakumova, Daryna. “Diplomatic Relations, Artificial Intelligence and Cyber Threats.” Global Challenges, no. 17, May 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/17/diplomatic-relations-artificial-intelligence-and-cyber-threats. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-193x-nx93.Dossier produced by the Research Office of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

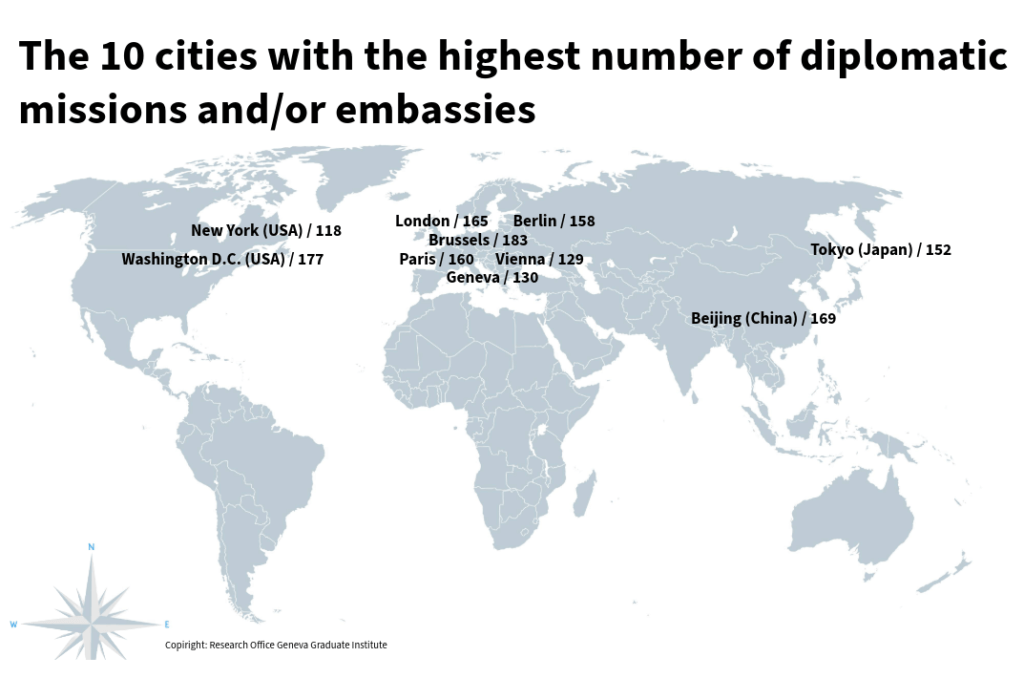

TABLE | The 20 Countries with the Most Diplomatic Missions in the World in 2024

| Country | Total number of posts | Embassies | Consulates | Permanent Missions | Other representations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 274 | 173 | 91 | 8 | 2 |

| USA | 271 | 168 | 83 | 11 | 8 |

| Turkey | 252 | 145 | 93 | 12 | 2 |

| Japan | 251 | 152 | 66 | 10 | 23 |

| France | 249 | 158 | 72 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | 230 | 143 | 74 | 10 | 3 |

| UK | 225 | 156 | 51 | 11 | 7 |

| Germany | 217 | 148 | 56 | 11 | 2 |

| Italy | 206 | 124 | 74 | 8 | 0 |

| Brazil | 205 | 135 | 58 | 12 | 2 |

| India | 201 | 142 | 50 | 5 | 4 |

| Spain | 190 | 114 | 65 | 10 | 1 |

| South Korea | 187 | 114 | 60 | 5 | 8 |

| Mexico | 161 | 80 | 71 | 8 | 2 |

| Canada | 157 | 98 | 38 | 11 | 10 |

| Argentina | 150 | 87 | 54 | 7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 149 | 106 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| Switzerland | 141 | 102 | 30 | 7 | 2 |

| Hungry | 140 | 87 | 43 | 7 | 3 |

| Poland | 135 | 91 | 33 | 9 | 2 |

All data taken from the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index 2024.

BOX 1 | Diplomatic Realism

Diplomatic realism, often simply referred to as realism, is a theory of international relations that emphasises the competitive and conflictual nature of relations between States. Here are some key principles of diplomatic realism:

- International anarchy: The international system is anarchic, meaning that there is no higher authority to regulate relations between States. States must therefore rely on their own means to ensure their security and interests.

- State sovereignty: States are the main actors in international relations. They are sovereign and act rationally to maximise their security and power.

- Power and national Interests: States seek to maximise their relative power in relation to other states. Power can be measured in terms of capabilities — military, economic, technological, etc. National interests, often defined in terms of security, survival and prosperity, guide the actions of States.

- Balance of power: States form alliances and adopt strategies to maintain a balance of power, thus preventing a single State or coalition of States from becoming too powerful and threatening their security.

- Inevitable conflict: Realists consider conflict to be an inevitable feature of international relations. States are in constant competition for resources, territory and influence, which can lead to conflict and war.

- Pessimism about cooperation: Realists are sceptical about the possibility of lasting international cooperation. They see international institutions and agreements as tools that States use to promote their national interests rather than as means of genuine cooperation.

Diplomatic realism has been influenced by thinkers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and more recently by modern theorists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. This theory provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of States in a world where security and survival are of paramount concern. This realist theory is one of the analytical frameworks for international relations, in addition to liberalism and constructivism. They all have in common that they are rooted in Western philosophy.

Source: David Ho, “Les théories chinoises des relations internationales: une brève introduction”, La Revue d’histoire militaire, 4 April 2024.

BOX 2 | The New Diplomacy

“New diplomacy” refers to an evolution in traditional diplomatic practices, marked by the emergence of new actors, new means of communication and new issues. It is a concept that has emerged in response to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, marked by globalisation and the growing interdependence of states. It contrasts with traditional diplomacy, which is state-based, secret and bilateral, embodied by foreign ministries and embassies.

- Expansion of diplomatic actors: While traditional diplomacy was monopolised by states, new diplomacy involves multiple actors. It includes non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies, local authorities (cities, regions), international organisations (UN, WTO, EU…), citizens and social movements.

- Transformation of tools and channels: Digital tools have profoundly changed diplomatic practices. Public diplomacy and “twiplomacy” (diplomacy via X and other networks) enable direct communication between diplomats and the public.

- Broadening of themes: The new diplomacy addresses complex global issues such as climate change, global health, human rights, migration, digital governance and gender equality. For instance, the climate negotiations at COP26 involved not only states, but also NGOs, businesses, indigenous peoples and young activists such as Greta Thunberg.

- Collaborative and multi-level approaches: Diplomacy is no longer just vertical (between governments), but also horizontal, via cooperation networks between cities (e.g. C40 Cities), universities and civil society.

- More transparent and responsive diplomacy. Negotiations are increasingly subject to pressure from public opinion, the media and real-time communication dynamics. This makes diplomacy more visible, but also more vulnerable to polarisation or communication effects.

In summary, new diplomacy is a more holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world. It seeks to address global challenges through cooperation, engagement with a diversity of actors, and the use of new tools and technologies.

BOX 3 | Figures on International Geneva and Impact of US Cuts on United Nations Funding

- 43 international organisations in the Lake Geneva area (38 in Geneva, 46 in total in Switzerland)

- 183 States represented

- About 750 non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- More than 4,000 visits per year of heads of state and government, ministers and other dignitaries

- In 2024, 36,460 people were employed in IOs, NGOs and permanent missions:

- 28,962 people employed in IOs

- 4,062 people employed in permanent missions

- 3,436 people employed in NGOs

- In 2024, the United States funded 22% of the UN regular budget, more than China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). But in 2025, it significantly reduced its financial contributions:

- Reduction of more than 80% for the UN regular budget, affecting more than 40 international organisations, including UNESCO and the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Suspension of USD 377 million for UNFPA, the UN agency for reproductive health, impacting 48 programmes in crisis areas such as Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine

- Cuts of USD 160 million for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), jeopardising global efforts to monitor avian influenza

- Estimated reduction of 30% for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), affecting more than 6,000 employees worldwide.

- To prevent staff layoffs due to the US funding freeze, the Canton of Geneva has allocated CHF 10 million and the City of Geneva CHF 2 million to support local NGOs.

Sources: République et canton de Genève, “Statistiques cantonales”. République et canton de Genève, Genève internationale, “Facts and Figures”. Confédération suisse, “Facts and Figures about International Geneva”. Better World Campaign, “Proposed FY25 Spending Bill for Foreign Operations Would Gut U.S. Global Standing”, 6 April 2025. United Nations Office at Geneva, “US Funding Cuts Confirmed, Ending Lifesaving Support for Women and Girls”, 27 February 2025. Susannah Savage and Michael Peel, “American Farmers Raise Alarm As US Cuts Funds for UN Bird Flu Fight”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025. International Organization for Migration, “Update on IOM Operations amid Budget Cuts ”, 18 March 2025. US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, United Nations Issues: US Funding to the UN System, by Luisa Blanchfield, IF10354, 9 April 2024. Frédéric Julliard, “Genève souffle le chaud et le froid sur les ONG”, Le Temps, 17 February 2025. Fanny Scuderi, “La ville de Genève alloue 2 millions de francs d’aide aux ONG”, 13 March 2025.

VIDEO | Former US Representative to the UN Amb. Sheba Crocker on Her Three Years in International Geneva

U.S. Mission Geneva

VIDEO | Diplomacy Today, with Stephan Klement, EU Diplomat and Special Adviser on Iran Nuclear Issue

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | La diplomatie de la restitution des œuvres d’art avec Amb. Angelo Dan

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute