Rethinking United Nations Mediation

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-zyaw-p135UN mediation is in crisis: in Gaza and Ukraine, the option to appoint a UN Special Envoy isn’t even on the table. In Syria and Yemen, existing Special Envoys have often been sidelined. Meanwhile, in Sudan and Iraq, UN political missions tasked with mediation have either been forced to withdraw or are on the verge of doing so.

What is driving this crisis? The answer lies in a combination of internal and external challenges to UN mediation efforts.

Internally, geopolitical competition has paralysed the UN Security Council (UNSC) on conflicts involving its permanent five members (the P5), such as Ukraine, Gaza, or Syria.On Ukraine, despite nearly a hundred meetings, the UNSC was unable for three years to adopt a single resolution. On Ukraine, despite nearly a hundred meetings, the UNSC was unable for three years to adopt a single resolution. In November 2024, within the span of a single week, Russia vetoed a resolution on Sudan, and the United States vetoed a resolution on Gaza. And between 2011 and 2023, 18 resolutions on Syria were vetoed in the UNSC. This inability to address some of the most atrocious conflicts of our time has tarnished the reputation of the UNSC — in principle, the main UN organ responsible for maintaining international peace and security — and has led to accusations of double standards, fuelling a broader legitimacy crisis. More specifically, the UNSC’s deadlock makes the job of UN Special Envoys — if they are appointed at all — more difficult, because they lack the leverage gained from a united UNSC.

External factors are also challenging UN mediation efforts. New actors have entered the mediation field, which is not inherently problematic, as mediation has long been a “crowded field”. The challenge, however, lies in the fact that the core principles of mediation that the UN upholds are increasingly being called into question. The UN’s approach to mediation emphasises conflict resolution, with the long-term aim of achieving sustainable peace through impartial and inclusive processes, even if the immediate goal may simply be to halt the violence. This approach is outlined in the United Nations Guidance for Effective Mediation adopted in 2012 and was long regarded as a standard for mediation. However, a shift toward conflict containment has recently emerged, prioritising violence reduction through exclusive and transactional deal-making rather than peace-making. This approach is often driven by states that leverage peace processes to advance their own geopolitical interests, rather than fostering long-term stability. a shift toward conflict containment has recently emerged, prioritising violence reduction through exclusive and transactional deal-making rather than peace-making. This is also because the deal-makers tend to be militarily involved in the conflict themselves, such as Russia in Syria or the US in Gaza. Because conflict parties have alternatives to turn to if they want to engage in a peace process and because they frequently depend politically or militarily on the deal-makers, their consent to UN-facilitated mediation processes is often weakened.

Due to these challenges, both internal and external, UN diplomats have seen their political influence in conflict contexts wane. They have lost the leverage of a legitimised and united UNSC and their approach to mediation has likewise been challenged by alternative actors that prioritise short-term deals over long-term peace. While this may seem bleak, we have not crossed a point of no return, but the way forward needs adaptation, strategy, and innovation.

Internally, bridge-building amongst the P5 and avoiding UNSC paralysis are more important than ever. One vital bridge is international law, as states have — at least in principle — once agreed on it. To maintain the legitimacy of the UN and avoid accusations of double standards, it is crucial for those states who are still committed to the rules-based order to put all their efforts into taking international law as a yardstick for decisions. Another strategy is coalition-building. A notable example is the March 2024 resolution on a ceasefire in Gaza. For the first time in history, all ten elected members (E10) of the UNSC jointly brought forward a resolution, successfully avoiding a US veto. This initiative demonstrates the power of coalitions among the E10, and highlights their ability to influence outcomes despite P5 divisions.

Externally, it is crucial to recognise that the diversity of mediation approaches can be a strength if harnessed effectively. This requires a case-by-case assessment to determine which actor is best positioned to lead a political effort. While the UN may not always take the lead, it plays a vital role in fostering unity of purpose among various peacemakers and leveraging its unique expertise on different aspects of mediation, such as ceasefire monitoring, confidence-building measures, and inclusion. At the same time, it is essential to maintain an approach to mediation that extends beyond merely containing violence. The fall of Bashar al-Assad in Syria in December 2024 serves as a stark reminder that military victories do not always hold in the long term and that political solutions are indispensable to address armed conflicts sustainably. It is therefore important for the UN to continue to champion longer-term, impartial, and inclusive approaches. Even when other actors — particularly states — broker agreements, the UN can still play an indispensable role by overseeing the implementation of these deals and by supporting the transition toward a more peaceful future. However, this requires the UN to be prepared and equipped to step in when needed, ensuring that its contributions remain impactful and relevant.

In the end, it is time to rethink mediation no longer in terms of high-level peace processes with the UN generally in the lead, but as a method that can be used in different, interlinked processes at various levels. This broader understanding allows for a more flexible, collaborative approach, where the UN can complement other efforts while leveraging its own unique strength: to garner the legitimacy of its universal membership to address conflicts in a sustainable way.

Electronic reference

Hellmüller, Sara. “Rethinking United Nations Mediation.” Global Challenges, no. 17, May 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/17/rethinking-united-nations-mediation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-zyaw-p135.Dossier produced by the Research Office of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

TABLE | The 20 Countries with the Most Diplomatic Missions in the World in 2024

| Country | Total number of posts | Embassies | Consulates | Permanent Missions | Other representations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 274 | 173 | 91 | 8 | 2 |

| USA | 271 | 168 | 83 | 11 | 8 |

| Turkey | 252 | 145 | 93 | 12 | 2 |

| Japan | 251 | 152 | 66 | 10 | 23 |

| France | 249 | 158 | 72 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | 230 | 143 | 74 | 10 | 3 |

| UK | 225 | 156 | 51 | 11 | 7 |

| Germany | 217 | 148 | 56 | 11 | 2 |

| Italy | 206 | 124 | 74 | 8 | 0 |

| Brazil | 205 | 135 | 58 | 12 | 2 |

| India | 201 | 142 | 50 | 5 | 4 |

| Spain | 190 | 114 | 65 | 10 | 1 |

| South Korea | 187 | 114 | 60 | 5 | 8 |

| Mexico | 161 | 80 | 71 | 8 | 2 |

| Canada | 157 | 98 | 38 | 11 | 10 |

| Argentina | 150 | 87 | 54 | 7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 149 | 106 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| Switzerland | 141 | 102 | 30 | 7 | 2 |

| Hungry | 140 | 87 | 43 | 7 | 3 |

| Poland | 135 | 91 | 33 | 9 | 2 |

All data taken from the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index 2024.

BOX 1 | Diplomatic Realism

Diplomatic realism, often simply referred to as realism, is a theory of international relations that emphasises the competitive and conflictual nature of relations between States. Here are some key principles of diplomatic realism:

- International anarchy: The international system is anarchic, meaning that there is no higher authority to regulate relations between States. States must therefore rely on their own means to ensure their security and interests.

- State sovereignty: States are the main actors in international relations. They are sovereign and act rationally to maximise their security and power.

- Power and national Interests: States seek to maximise their relative power in relation to other states. Power can be measured in terms of capabilities — military, economic, technological, etc. National interests, often defined in terms of security, survival and prosperity, guide the actions of States.

- Balance of power: States form alliances and adopt strategies to maintain a balance of power, thus preventing a single State or coalition of States from becoming too powerful and threatening their security.

- Inevitable conflict: Realists consider conflict to be an inevitable feature of international relations. States are in constant competition for resources, territory and influence, which can lead to conflict and war.

- Pessimism about cooperation: Realists are sceptical about the possibility of lasting international cooperation. They see international institutions and agreements as tools that States use to promote their national interests rather than as means of genuine cooperation.

Diplomatic realism has been influenced by thinkers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and more recently by modern theorists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. This theory provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of States in a world where security and survival are of paramount concern. This realist theory is one of the analytical frameworks for international relations, in addition to liberalism and constructivism. They all have in common that they are rooted in Western philosophy.

Source: David Ho, “Les théories chinoises des relations internationales: une brève introduction”, La Revue d’histoire militaire, 4 April 2024.

BOX 2 | The New Diplomacy

“New diplomacy” refers to an evolution in traditional diplomatic practices, marked by the emergence of new actors, new means of communication and new issues. It is a concept that has emerged in response to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, marked by globalisation and the growing interdependence of states. It contrasts with traditional diplomacy, which is state-based, secret and bilateral, embodied by foreign ministries and embassies.

- Expansion of diplomatic actors: While traditional diplomacy was monopolised by states, new diplomacy involves multiple actors. It includes non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies, local authorities (cities, regions), international organisations (UN, WTO, EU…), citizens and social movements.

- Transformation of tools and channels: Digital tools have profoundly changed diplomatic practices. Public diplomacy and “twiplomacy” (diplomacy via X and other networks) enable direct communication between diplomats and the public.

- Broadening of themes: The new diplomacy addresses complex global issues such as climate change, global health, human rights, migration, digital governance and gender equality. For instance, the climate negotiations at COP26 involved not only states, but also NGOs, businesses, indigenous peoples and young activists such as Greta Thunberg.

- Collaborative and multi-level approaches: Diplomacy is no longer just vertical (between governments), but also horizontal, via cooperation networks between cities (e.g. C40 Cities), universities and civil society.

- More transparent and responsive diplomacy. Negotiations are increasingly subject to pressure from public opinion, the media and real-time communication dynamics. This makes diplomacy more visible, but also more vulnerable to polarisation or communication effects.

In summary, new diplomacy is a more holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world. It seeks to address global challenges through cooperation, engagement with a diversity of actors, and the use of new tools and technologies.

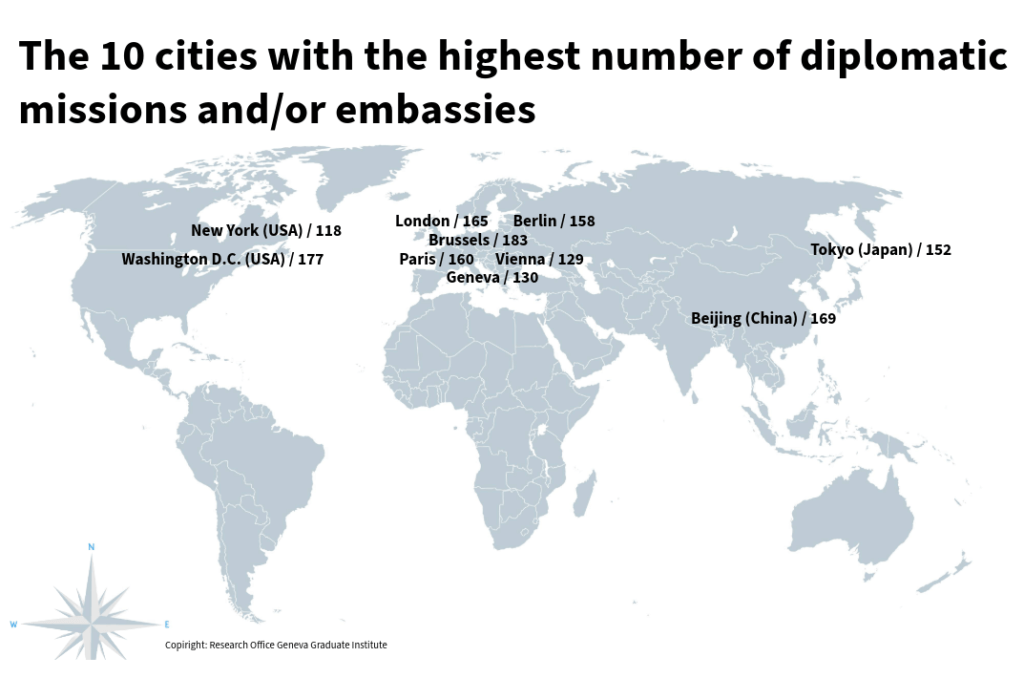

BOX 3 | Figures on International Geneva and Impact of US Cuts on United Nations Funding

- 43 international organisations in the Lake Geneva area (38 in Geneva, 46 in total in Switzerland)

- 183 States represented

- About 750 non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- More than 4,000 visits per year of heads of state and government, ministers and other dignitaries

- In 2024, 36,460 people were employed in IOs, NGOs and permanent missions:

- 28,962 people employed in IOs

- 4,062 people employed in permanent missions

- 3,436 people employed in NGOs

- In 2024, the United States funded 22% of the UN regular budget, more than China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). But in 2025, it significantly reduced its financial contributions:

- Reduction of more than 80% for the UN regular budget, affecting more than 40 international organisations, including UNESCO and the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Suspension of USD 377 million for UNFPA, the UN agency for reproductive health, impacting 48 programmes in crisis areas such as Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine

- Cuts of USD 160 million for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), jeopardising global efforts to monitor avian influenza

- Estimated reduction of 30% for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), affecting more than 6,000 employees worldwide.

- To prevent staff layoffs due to the US funding freeze, the Canton of Geneva has allocated CHF 10 million and the City of Geneva CHF 2 million to support local NGOs.

Sources: République et canton de Genève, “Statistiques cantonales”. République et canton de Genève, Genève internationale, “Facts and Figures”. Confédération suisse, “Facts and Figures about International Geneva”. Better World Campaign, “Proposed FY25 Spending Bill for Foreign Operations Would Gut U.S. Global Standing”, 6 April 2025. United Nations Office at Geneva, “US Funding Cuts Confirmed, Ending Lifesaving Support for Women and Girls”, 27 February 2025. Susannah Savage and Michael Peel, “American Farmers Raise Alarm As US Cuts Funds for UN Bird Flu Fight”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025. International Organization for Migration, “Update on IOM Operations amid Budget Cuts ”, 18 March 2025. US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, United Nations Issues: US Funding to the UN System, by Luisa Blanchfield, IF10354, 9 April 2024. Frédéric Julliard, “Genève souffle le chaud et le froid sur les ONG”, Le Temps, 17 February 2025. Fanny Scuderi, “La ville de Genève alloue 2 millions de francs d’aide aux ONG”, 13 March 2025.

VIDEO | Former US Representative to the UN Amb. Sheba Crocker on Her Three Years in International Geneva

U.S. Mission Geneva

VIDEO | Diplomacy Today, with Stephan Klement, EU Diplomat and Special Adviser on Iran Nuclear Issue

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | La diplomatie de la restitution des œuvres d’art avec Amb. Angelo Dan

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute