The Geneva Graduate Institute and the Training of Diplomats in the Context of Decolonisation

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-2bmn-q911In July 1969, the Central African diplomat Emmanuel Bongopassi thanked the Institut universitaire d’études du développement (IUED) — then known as the Institut africain de Genève — “for the training of men with enormous responsibilities and whose future is not yet defined”. Bongopassi had spent 11 months in Geneva and followed courses at the IUED as a Carnegie Fellow. “Your courses”, he wrote, “have instilled some of my colleagues with confidence in themselves and in the future.”

Letter from Emmanuel Bongopassi to Pierre Bungener, Director of the Institut africain de Genève. 14 July 1969. Geneva Graduate Institute Archives, “IUED 2/17. Conseil de fondation de l’Institut Africain de Genève. Séance du 19 février 1969”.

Letter from Emmanuel Bongopassi to Pierre Bungener, Director of the Institut africain de Genève. 14 July 1969. Geneva Graduate Institute Archives, “IUED 2/17. Conseil de fondation de l’Institut Africain de Genève. Séance du 19 février 1969”.Like Bongopassi, thousands of mostly male students and interns from recently independent countries went abroad during the 1960s and 1970s for further education. In what follows, we discuss Switzerland’s and particularly Geneva’s role in what we could term the Cold War of education. For this, we turn to the history of the Geneva Graduate Institute’s predecessors, the Institut universitaire de hautes études internationales (the IUHEI, founded in 1927) and the IUED (founded in 1961).

With formal independence, governments across Africa and Asia faced the task of building up and restructuring their administrations and hiring local staff, including in the fields of diplomacy and foreign affairs. Since the colonial system had in most cases neglected the training of subject populations and invested little in education, these governments urgently needed qualified personnel. In this context, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in an educational Cold War, hoping to win recently independent countries and their students over to their respective causes. The two superpowers used all sorts of educational tools to this end, such as scholarships, the dispatch of teachers, university exchanges, and the set-up of local academic institutions. Other countries followed and created their own offers, including Switzerland.

In the early 1950s, Switzerland was internationally isolated. It voluntarily abstained from joining international organisations, particularly the United Nations. It was also a time when Switzerland was reproached for its interpretation of neutrality during World War II, in particular for having allowed collaboration with the Axis powers. To restore its image, Switzerland sought to redefine its neutrality by adding the component of “solidarity”. Development assistance was one way of demonstrating this solidarity. It was carried out by the Service pour l’assistance technique, established in 1960 and the predecessor of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). SDC officials deemed Switzerland particularly suited to educating students from former colonies, because Switzerland had had no colonies of its own and, thanks to its neutrality, stood between the two blocs in the Cold War. This, it was hoped, would attract students suspicious of the two superpowers’ educational offers.

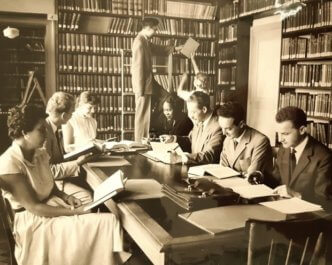

Students in the library in the villa Barton. Geneva Graduate Institute Archives, “HEI 2521/6 Photos diverses Institut 1951-1968”.

Students in the library in the villa Barton. Geneva Graduate Institute Archives, “HEI 2521/6 Photos diverses Institut 1951-1968”.

Throughout the 1960s, the IUHEI became a major academic partner of the SDC. Its director, Jacques Freymond, skilfully positioned his institution as a privileged place for the training of elites. He was convinced that science had an important role to play in the affirmation of Western values. The elites of the Third World — “impregnated” with Marxism — had now to be “reconquered”. With the support of US American philanthropic foundations, the IUHEI established a diplomatic training programme for students from the Third World. The aim was to familiarise diplomats from decolonised countries with their Western counterparts and to contribute to the creation of an international diplomatic elite that shared the same values and practices. The SDC also mandated the IUHEI to set up a school of diplomacy in Trinidad and Tobago after Eric Williams, head of the Trinidadian government and leader of the independence movement, had called on Switzerland to train his diplomats. In the framework of this cooperation, the IUHEI drafted the new institution’s statutes, defined processes of admission, elaborated curricula and even sent some of its professors to Trinidad and Tobago to teach. In the 1970s, the IUHEI would establish other schools of diplomacy in Cameroon and Kenya. In Switzerland, Jacques Freymond lobbied for the establishment of a specialised institution for the training of African elites, which led to the creation of the IUED in 1961.

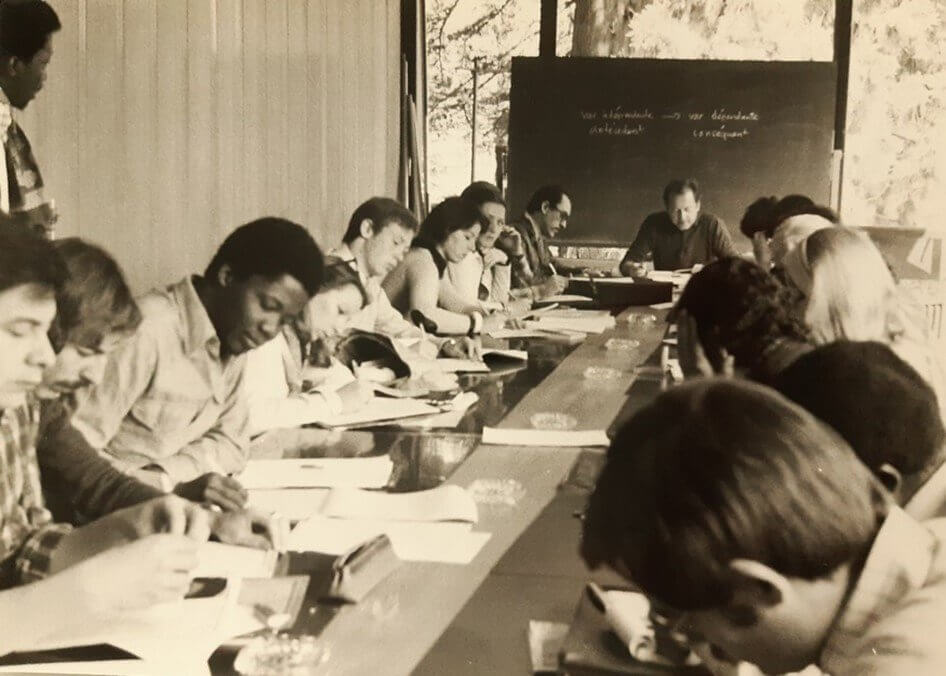

The first decade of the IUED’s existence was difficult because of the diverging and sometimes contradictory interests and expectations of the parties involved in its establishment. Its main funder, the canton of Geneva, took a hands-off approach; the IUHEI considered it a complement to its own offers; the University of Geneva feared competition and sabotaged the conferral of university degrees; while SDC officials viewed the IUED with suspicion due to it being out of their control. To prove its usefulness to the SDC, the IUED organised two six-month training courses for groups of ten Nigerian diplomats in 1963 and 1965, funded by the SDC. The IUED meticulously planned the diplomats’ stay: they received training in international law by teachers from the IUHEI, followed intensive French courses and did visits all over Switzerland. However, the training of diplomats never became a priority for the IUED. Over the course of the 1960s, it reoriented its focus from African studies to development studies, forming an emerging class of development “experts”, who — at least in the case of Switzerland — would often work closely together with their diplomatic counterparts.

In conclusion, both the IUHEI and the IUED seized the opportunity to train diplomats from recently independent countries, so as to obtain funding from government and philanthropic actors and to prove their relevance to the public. Whereas the IUHEI continued this mission beyond the high period of decolonisation, the IUED focussed its activities on the development sector, viewing its older sibling as part of the system that much of its faculty criticised. Whereas the IUHEI continued this mission beyond the high period of decolonisation, the IUED focussed its activities on the development sector, viewing its older sibling as part of the system that much of its faculty criticised. As for the students themselves, we only have fragmentary evidence regarding their experiences in Geneva. Emmanuel Bongopassi, over the course of his career, rose to the rank of ambassador. When he wrote his letter to the IUED in 1969, he quoted Marx to affirm the place of African nations in the world.

Electronic reference

Roy, Charlotte, and Nicolas Hafner. “The Geneva Graduate Institute and the Training of Diplomats in the Context of Decolonisation.” Global Challenges, no. 17, May 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/17/the-geneva-graduate-institute-and-the-training-of-diplomats-in-the-context-of-decolonisation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-2bmn-q911.Dossier produced by the Research Office of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

TABLE | The 20 Countries with the Most Diplomatic Missions in the World in 2024

| Country | Total number of posts | Embassies | Consulates | Permanent Missions | Other representations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 274 | 173 | 91 | 8 | 2 |

| USA | 271 | 168 | 83 | 11 | 8 |

| Turkey | 252 | 145 | 93 | 12 | 2 |

| Japan | 251 | 152 | 66 | 10 | 23 |

| France | 249 | 158 | 72 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | 230 | 143 | 74 | 10 | 3 |

| UK | 225 | 156 | 51 | 11 | 7 |

| Germany | 217 | 148 | 56 | 11 | 2 |

| Italy | 206 | 124 | 74 | 8 | 0 |

| Brazil | 205 | 135 | 58 | 12 | 2 |

| India | 201 | 142 | 50 | 5 | 4 |

| Spain | 190 | 114 | 65 | 10 | 1 |

| South Korea | 187 | 114 | 60 | 5 | 8 |

| Mexico | 161 | 80 | 71 | 8 | 2 |

| Canada | 157 | 98 | 38 | 11 | 10 |

| Argentina | 150 | 87 | 54 | 7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 149 | 106 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| Switzerland | 141 | 102 | 30 | 7 | 2 |

| Hungry | 140 | 87 | 43 | 7 | 3 |

| Poland | 135 | 91 | 33 | 9 | 2 |

All data taken from the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index 2024.

BOX 1 | Diplomatic Realism

Diplomatic realism, often simply referred to as realism, is a theory of international relations that emphasises the competitive and conflictual nature of relations between States. Here are some key principles of diplomatic realism:

- International anarchy: The international system is anarchic, meaning that there is no higher authority to regulate relations between States. States must therefore rely on their own means to ensure their security and interests.

- State sovereignty: States are the main actors in international relations. They are sovereign and act rationally to maximise their security and power.

- Power and national Interests: States seek to maximise their relative power in relation to other states. Power can be measured in terms of capabilities — military, economic, technological, etc. National interests, often defined in terms of security, survival and prosperity, guide the actions of States.

- Balance of power: States form alliances and adopt strategies to maintain a balance of power, thus preventing a single State or coalition of States from becoming too powerful and threatening their security.

- Inevitable conflict: Realists consider conflict to be an inevitable feature of international relations. States are in constant competition for resources, territory and influence, which can lead to conflict and war.

- Pessimism about cooperation: Realists are sceptical about the possibility of lasting international cooperation. They see international institutions and agreements as tools that States use to promote their national interests rather than as means of genuine cooperation.

Diplomatic realism has been influenced by thinkers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and more recently by modern theorists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. This theory provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of States in a world where security and survival are of paramount concern. This realist theory is one of the analytical frameworks for international relations, in addition to liberalism and constructivism. They all have in common that they are rooted in Western philosophy.

Source: David Ho, “Les théories chinoises des relations internationales: une brève introduction”, La Revue d’histoire militaire, 4 April 2024.

BOX 2 | The New Diplomacy

“New diplomacy” refers to an evolution in traditional diplomatic practices, marked by the emergence of new actors, new means of communication and new issues. It is a concept that has emerged in response to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, marked by globalisation and the growing interdependence of states. It contrasts with traditional diplomacy, which is state-based, secret and bilateral, embodied by foreign ministries and embassies.

- Expansion of diplomatic actors: While traditional diplomacy was monopolised by states, new diplomacy involves multiple actors. It includes non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies, local authorities (cities, regions), international organisations (UN, WTO, EU…), citizens and social movements.

- Transformation of tools and channels: Digital tools have profoundly changed diplomatic practices. Public diplomacy and “twiplomacy” (diplomacy via X and other networks) enable direct communication between diplomats and the public.

- Broadening of themes: The new diplomacy addresses complex global issues such as climate change, global health, human rights, migration, digital governance and gender equality. For instance, the climate negotiations at COP26 involved not only states, but also NGOs, businesses, indigenous peoples and young activists such as Greta Thunberg.

- Collaborative and multi-level approaches: Diplomacy is no longer just vertical (between governments), but also horizontal, via cooperation networks between cities (e.g. C40 Cities), universities and civil society.

- More transparent and responsive diplomacy. Negotiations are increasingly subject to pressure from public opinion, the media and real-time communication dynamics. This makes diplomacy more visible, but also more vulnerable to polarisation or communication effects.

In summary, new diplomacy is a more holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world. It seeks to address global challenges through cooperation, engagement with a diversity of actors, and the use of new tools and technologies.

BOX 3 | Figures on International Geneva and Impact of US Cuts on United Nations Funding

- 43 international organisations in the Lake Geneva area (38 in Geneva, 46 in total in Switzerland)

- 183 States represented

- About 750 non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- More than 4,000 visits per year of heads of state and government, ministers and other dignitaries

- In 2024, 36,460 people were employed in IOs, NGOs and permanent missions:

- 28,962 people employed in IOs

- 4,062 people employed in permanent missions

- 3,436 people employed in NGOs

- In 2024, the United States funded 22% of the UN regular budget, more than China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). But in 2025, it significantly reduced its financial contributions:

- Reduction of more than 80% for the UN regular budget, affecting more than 40 international organisations, including UNESCO and the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Suspension of USD 377 million for UNFPA, the UN agency for reproductive health, impacting 48 programmes in crisis areas such as Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine

- Cuts of USD 160 million for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), jeopardising global efforts to monitor avian influenza

- Estimated reduction of 30% for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), affecting more than 6,000 employees worldwide.

- To prevent staff layoffs due to the US funding freeze, the Canton of Geneva has allocated CHF 10 million and the City of Geneva CHF 2 million to support local NGOs.

Sources: République et canton de Genève, “Statistiques cantonales”. République et canton de Genève, Genève internationale, “Facts and Figures”. Confédération suisse, “Facts and Figures about International Geneva”. Better World Campaign, “Proposed FY25 Spending Bill for Foreign Operations Would Gut U.S. Global Standing”, 6 April 2025. United Nations Office at Geneva, “US Funding Cuts Confirmed, Ending Lifesaving Support for Women and Girls”, 27 February 2025. Susannah Savage and Michael Peel, “American Farmers Raise Alarm As US Cuts Funds for UN Bird Flu Fight”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025. International Organization for Migration, “Update on IOM Operations amid Budget Cuts ”, 18 March 2025. US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, United Nations Issues: US Funding to the UN System, by Luisa Blanchfield, IF10354, 9 April 2024. Frédéric Julliard, “Genève souffle le chaud et le froid sur les ONG”, Le Temps, 17 February 2025. Fanny Scuderi, “La ville de Genève alloue 2 millions de francs d’aide aux ONG”, 13 March 2025.

VIDEO | Former US Representative to the UN Amb. Sheba Crocker on Her Three Years in International Geneva

U.S. Mission Geneva

VIDEO | Diplomacy Today, with Stephan Klement, EU Diplomat and Special Adviser on Iran Nuclear Issue

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | La diplomatie de la restitution des œuvres d’art avec Amb. Angelo Dan

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute