The Modern Diplomat: Exposed, Endangered and Indispensable

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-sazw-8f79“Even the least thoughtful of diplomats must look nowadays with dismay upon the field of his professional activity.” In this way the anonymous author “H” opened an essay in the April 1937 issue of the journal Foreign Affairs. A sentiment not entirely absent among today’s diplomats as they observe sudden twists and turns in the political landscape that undermine years, if not decades, of effort to negotiate complex international treaties related to climate change or other global issues.

A century ago, diplomacy was effectively about state-to-state relations. “H” defined the purpose of diplomacy as the ability “to develop and diversify international relationships, to avoid international conflicts, to foster understanding and thereby promote confidence, tolerance and mutual esteem.” “H” believed diplomacy and diplomats had “failed and failed miserably”. A few months later Japan attacked China. A year later, in Munich, Britain and France effectively ceded parts of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany in a forlorn hope of preventing a wide European war. When Germany attacked Poland on 1 September 1939 diplomacy had clearly failed to prevent World War II.

Does this mean that diplomats were useless in the 1930s? Hardly. Their collective role at the time was instrumental to the outcomes; German diplomats were, in fact, quite successful in achieving the goals they were expected to achieve. But, as always, even the top diplomats of the 1930s walked a fine line between making and implementing policy. Their power, as that of diplomats across time and space, was curtailed by the polities they served.

The above seems straightforward. The classic role of a diplomat is, after all, to provide a service. From antiquity to the Renaissance, diplomats tended to be chosen for their closeness and loyalty to political leaders. Their tasks were sporadic: to negotiate a treaty or issue an offer of friendship or a demand of submission. It could be dangerous: in 481 BCE the ambassadors of the Persian king Xerxes were thrown into a well by the orders of the Spartan king Leonidas. Similar fates befell envoys of Genghis Khan and many others — the messenger was, indeed, often killed because the recipient did not like the message.

By the 16th century, permanent embassies began to emerge in Italy and other parts of Europe. The concept of diplomatic immunity became more widespread and diplomacy gradually emerged as a professional career. In subsequent centuries the role of diplomacy and diplomats was an essential part of the macroprocesses — imperialism and nation-building — shaping relationships across the globe. Claims for sovereignty required diplomatic recognition and the day-to-day management of affairs between sovereign states depended upon it. Yet, as became patently clear long before “H” wrote his pessimistic treatise in 1937, modern diplomats were rarely more independent actors than their predecessors in antiquity or the early modern era. They followed orders from the capital and their success was usually measured by an ability to fulfil those dictates.

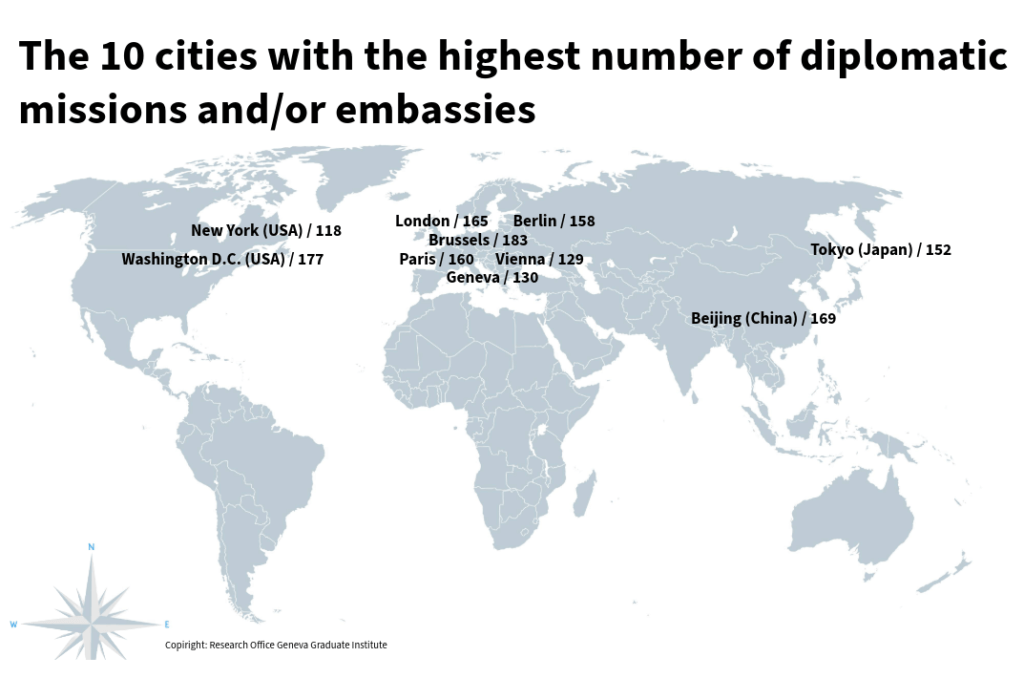

Since World War II, diplomacy has become increasingly institutionalised and professionalised. The Cold War was one cause: the Americans and the Soviets invested in building highly skilled foreign services to help safeguard their increasingly global interests. Diplomacy was, of course, instrumental in keeping the superpowers from direct military confrontation.Diplomacy was, of course, instrumental in keeping the superpowers from direct military confrontation. But the professionalisation of diplomacy also reflected the new postwar international system. The rise of international institutions prompted an increase in diplomatic representation from all countries in places like Geneva. Perhaps most importantly, there was decolonisation: newfound sovereignty and diplomatic representation were, in effect, two sides of the same coin. As the number of sovereign states effectively doubled between 1945 and 2025, the number of diplomats mushroomed.

While there are more diplomats working for more countries, there is, of course, another massive difference between the diplomats that tried to avoid World War II and those operational today. If the invention of the telegraph revolutionised communications in the 19th century, technology has further transformed the role of diplomats in the 21st. With the rise of social media, instant messaging, and 24/7 news cycles, diplomats today must navigate a fast-paced, highly public environment. Diplomats now use these tools not only to communicate with foreign governments but also to engage with the global public.

It is this that fundamentally differentiates the 21st century diplomat from their predecessors. The diplomat’s role has become far more transparent — the kind of backchannels that were still a staple of diplomacy during the Cold War era have become almost obsolete. Just observing the current quandaries of peace making in the Middle East and Ukraine, one is struck by the open discussion about peace terms, red lines, and expectations. It is difficult to imagine the kind of secrecy that, say, Henry Kissinger employed in his (not always successful) negotiations in the 1970s. Whether this difficulty of observing secrecy and utilising backchannels is entirely a positive development is debatable.

In 1937 “H” worried that diplomats would have little success going forward as “new causes of conflict between nations are being added to those which the past has accustomed us to consider as usual, if not inevitable”. In 2025, almost a century later, being a diplomat is far from straightforward. Aside from the uncertainties that have shaken international relations since Donald Trump took over the US presidency, there is so much else that makes the job of an envoy to any nation a massively complex undertaking. Much of this has to do with technology. A 300-character message on X can be far more influential than a secret memo.Just observing the current quandaries of peace making in the Middle East and Ukraine, one is struck by the open discussion about peace terms, red lines, and expectations.

Yet, it seems obvious that there is a value not only in diplomacy but in the confidentiality that diplomats have traditionally enjoyed. It is difficult to see how relations among states are best served by total transparency, with the ongoing efforts to bring about an end to war between Russia and Ukraine being a case in point. Yet, as there is no turning back the clock on technological change or the constant demand for information, it is diplomats and diplomacy that must adapt.

Electronic reference

Hanhimäki, Jussi. “The Modern Diplomat: Exposed, Endangered and Indispensable.” Global Challenges, no. 17, May 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/17/the-modern-diplomat-exposed-endangered-and-indispensable. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-sazw-8f79.Dossier produced by the Research Office of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

TABLE | The 20 Countries with the Most Diplomatic Missions in the World in 2024

| Country | Total number of posts | Embassies | Consulates | Permanent Missions | Other representations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 274 | 173 | 91 | 8 | 2 |

| USA | 271 | 168 | 83 | 11 | 8 |

| Turkey | 252 | 145 | 93 | 12 | 2 |

| Japan | 251 | 152 | 66 | 10 | 23 |

| France | 249 | 158 | 72 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | 230 | 143 | 74 | 10 | 3 |

| UK | 225 | 156 | 51 | 11 | 7 |

| Germany | 217 | 148 | 56 | 11 | 2 |

| Italy | 206 | 124 | 74 | 8 | 0 |

| Brazil | 205 | 135 | 58 | 12 | 2 |

| India | 201 | 142 | 50 | 5 | 4 |

| Spain | 190 | 114 | 65 | 10 | 1 |

| South Korea | 187 | 114 | 60 | 5 | 8 |

| Mexico | 161 | 80 | 71 | 8 | 2 |

| Canada | 157 | 98 | 38 | 11 | 10 |

| Argentina | 150 | 87 | 54 | 7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 149 | 106 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| Switzerland | 141 | 102 | 30 | 7 | 2 |

| Hungry | 140 | 87 | 43 | 7 | 3 |

| Poland | 135 | 91 | 33 | 9 | 2 |

All data taken from the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index 2024.

BOX 1 | Diplomatic Realism

Diplomatic realism, often simply referred to as realism, is a theory of international relations that emphasises the competitive and conflictual nature of relations between States. Here are some key principles of diplomatic realism:

- International anarchy: The international system is anarchic, meaning that there is no higher authority to regulate relations between States. States must therefore rely on their own means to ensure their security and interests.

- State sovereignty: States are the main actors in international relations. They are sovereign and act rationally to maximise their security and power.

- Power and national Interests: States seek to maximise their relative power in relation to other states. Power can be measured in terms of capabilities — military, economic, technological, etc. National interests, often defined in terms of security, survival and prosperity, guide the actions of States.

- Balance of power: States form alliances and adopt strategies to maintain a balance of power, thus preventing a single State or coalition of States from becoming too powerful and threatening their security.

- Inevitable conflict: Realists consider conflict to be an inevitable feature of international relations. States are in constant competition for resources, territory and influence, which can lead to conflict and war.

- Pessimism about cooperation: Realists are sceptical about the possibility of lasting international cooperation. They see international institutions and agreements as tools that States use to promote their national interests rather than as means of genuine cooperation.

Diplomatic realism has been influenced by thinkers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and more recently by modern theorists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. This theory provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of States in a world where security and survival are of paramount concern. This realist theory is one of the analytical frameworks for international relations, in addition to liberalism and constructivism. They all have in common that they are rooted in Western philosophy.

Source: David Ho, “Les théories chinoises des relations internationales: une brève introduction”, La Revue d’histoire militaire, 4 April 2024.

BOX 2 | The New Diplomacy

“New diplomacy” refers to an evolution in traditional diplomatic practices, marked by the emergence of new actors, new means of communication and new issues. It is a concept that has emerged in response to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, marked by globalisation and the growing interdependence of states. It contrasts with traditional diplomacy, which is state-based, secret and bilateral, embodied by foreign ministries and embassies.

- Expansion of diplomatic actors: While traditional diplomacy was monopolised by states, new diplomacy involves multiple actors. It includes non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies, local authorities (cities, regions), international organisations (UN, WTO, EU…), citizens and social movements.

- Transformation of tools and channels: Digital tools have profoundly changed diplomatic practices. Public diplomacy and “twiplomacy” (diplomacy via X and other networks) enable direct communication between diplomats and the public.

- Broadening of themes: The new diplomacy addresses complex global issues such as climate change, global health, human rights, migration, digital governance and gender equality. For instance, the climate negotiations at COP26 involved not only states, but also NGOs, businesses, indigenous peoples and young activists such as Greta Thunberg.

- Collaborative and multi-level approaches: Diplomacy is no longer just vertical (between governments), but also horizontal, via cooperation networks between cities (e.g. C40 Cities), universities and civil society.

- More transparent and responsive diplomacy. Negotiations are increasingly subject to pressure from public opinion, the media and real-time communication dynamics. This makes diplomacy more visible, but also more vulnerable to polarisation or communication effects.

In summary, new diplomacy is a more holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world. It seeks to address global challenges through cooperation, engagement with a diversity of actors, and the use of new tools and technologies.

BOX 3 | Figures on International Geneva and Impact of US Cuts on United Nations Funding

- 43 international organisations in the Lake Geneva area (38 in Geneva, 46 in total in Switzerland)

- 183 States represented

- About 750 non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- More than 4,000 visits per year of heads of state and government, ministers and other dignitaries

- In 2024, 36,460 people were employed in IOs, NGOs and permanent missions:

- 28,962 people employed in IOs

- 4,062 people employed in permanent missions

- 3,436 people employed in NGOs

- In 2024, the United States funded 22% of the UN regular budget, more than China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). But in 2025, it significantly reduced its financial contributions:

- Reduction of more than 80% for the UN regular budget, affecting more than 40 international organisations, including UNESCO and the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Suspension of USD 377 million for UNFPA, the UN agency for reproductive health, impacting 48 programmes in crisis areas such as Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine

- Cuts of USD 160 million for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), jeopardising global efforts to monitor avian influenza

- Estimated reduction of 30% for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), affecting more than 6,000 employees worldwide.

- To prevent staff layoffs due to the US funding freeze, the Canton of Geneva has allocated CHF 10 million and the City of Geneva CHF 2 million to support local NGOs.

Sources: République et canton de Genève, “Statistiques cantonales”. République et canton de Genève, Genève internationale, “Facts and Figures”. Confédération suisse, “Facts and Figures about International Geneva”. Better World Campaign, “Proposed FY25 Spending Bill for Foreign Operations Would Gut U.S. Global Standing”, 6 April 2025. United Nations Office at Geneva, “US Funding Cuts Confirmed, Ending Lifesaving Support for Women and Girls”, 27 February 2025. Susannah Savage and Michael Peel, “American Farmers Raise Alarm As US Cuts Funds for UN Bird Flu Fight”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025. International Organization for Migration, “Update on IOM Operations amid Budget Cuts ”, 18 March 2025. US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, United Nations Issues: US Funding to the UN System, by Luisa Blanchfield, IF10354, 9 April 2024. Frédéric Julliard, “Genève souffle le chaud et le froid sur les ONG”, Le Temps, 17 February 2025. Fanny Scuderi, “La ville de Genève alloue 2 millions de francs d’aide aux ONG”, 13 March 2025.

VIDEO | Former US Representative to the UN Amb. Sheba Crocker on Her Three Years in International Geneva

U.S. Mission Geneva

VIDEO | Diplomacy Today, with Stephan Klement, EU Diplomat and Special Adviser on Iran Nuclear Issue

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | La diplomatie de la restitution des œuvres d’art avec Amb. Angelo Dan

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute