The New Trade of Trade Diplomacy: What Role for Trade Negotiators in a Trade World on Fire?

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-bnex-f224For much of the 20th century, trade diplomats laboured in splendid isolation. Like Geneva watchmakers, they slowly but steadily fixed the technicalities of import tariffs and customs procedures. Meeting in smoke-filled backrooms on the shores of Lac Léman, far removed from national capitals and democratic scrutiny, they prided themselves on gradually liberalising trade flows in ways that, according to economic theory, would benefit everyone.

In the 1990s, as globalisation progressed and started to show its dark side, labour unions and NGOs pushed back against this gilded trade diplomacy. They urged political leaders to take back control and address the negative social and environmental spill-over effects of trade. Trade diplomats paid lip service to these calls, adding vaguely worded and hard-to-enforce social and environmental clauses in regional trade agreements. The essence of the “trade diplomacy game”, however, remained unchanged, especially at the Geneva-based World Trade Organization (WTO) where developing countries blocked any social or environmental discussions as hidden trade protectionism. This, combined with the accession of China (2001) and other state-run economies to the WTO, stalled modernisation of the multilateral trading system. WTO reform needs consensus and as economic, technological and political diversity increased, adaptation only became harder. In the meantime, even the business community lost interest. Things simply moved too slowly, or not at all.No longer seen as an end in itself, trade is being weaponised to achieve non-economic goals

Then came the perfect storm, which eventually did revolutionise the trade of trade diplomacy. The 2008 global financial crisis may have marked “peak globalisation”. It took another decade for the dominos to really fall: Brexit, Trump 1.0, Covid-19, the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, Trump 2.0.

What does the job of a trade negotiator look like today?

Firstly, trade diplomats are no longer technical tariff nerds. Trade has become quintessentially political. No longer seen as an end in itself, trade is being weaponised to achieve non-economic goals ranging from deforestation, climate change and national security to technological dominance and territorial expansion.

Secondly, though WTO reform discussions continue like Groundhog Day, the centre of gravity has moved from multilateral talks in Geneva to bilateral posturing and deal-making in national capitals. Trade diplomats may still be posted or fly to Geneva. Yet, they no longer report Geneva results back to capital. Instead, they explain or try to explain in Geneva what is happening at home.though WTO reform discussions continue like Groundhog Day, the centre of gravity has moved from multilateral talks in Geneva to bilateral posturing and deal-making in national capitals.

Thirdly, both the form and the substance of trade agreements have changed. It used to be WTO and all-encompassing free trade agreements concluded as “forever treaties” with no time limit and only one goal: increasing liberalisation (as the Geneva saying goes: “trade liberalisation is like riding a bicycle: you can never stop doing it, because if you do you will fall off”). Today, it is mini-deals, mostly bilateral, on critical minerals, green steel, border security, digital trade or sustainable energy and investment. Deals which are far from “forever” and require regular updating. Modern trade deals are also not necessarily liberalising trade. Instead, most address side effects of trade such as environmental risks, labour standards or supply chain disruptions. Tariffs are the new normal. As President Trump declares repeatedly, “tariff is the most beautiful word in the dictionary”.

Finally, because of their increased societal and political relevance, trade diplomats can no longer work in splendid isolation. They need to engage with politicians, the business community as well as civil society, not only to be able to “sell” their trade deals at home, but also to gather expertise and evidence to make the right deal in the first place, a deal that can also subsequently be supported and implemented by those it affects.Tariffs are the new normal.

Where does this leave the trade of trade diplomacy? It has certainly become more interesting and challenging (except for those who prefer working quietly in a corner). It is fast-paced, volatile and highly political. It is increasingly based on ad hoc, power and national interest-driven bargains, more than longstanding international rules fixed in stone. Exhilarating as this may sound, the likely victims of this new trade are obvious: smaller and poorer countries, global commons as well as weaker economic operators who may be left out of the “high politics” game and for whom the uncertainty and fragmentation of global trade risks shutting them out of foreign markets and the welfare gains that come with it.

Electronic reference

Pauwelyn, Joost. “The New Trade of Trade Diplomacy: What Role for Trade Negotiators in a Trade World on Fire?” Global Challenges, no. 17, May 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/17/the-new-trade-of-trade-diplomacy-what-role-for-trade-negotiators-in-a-trade-world-on-fire. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-bnex-f224.Dossier produced by the Research Office of the Geneva Graduate Institute.

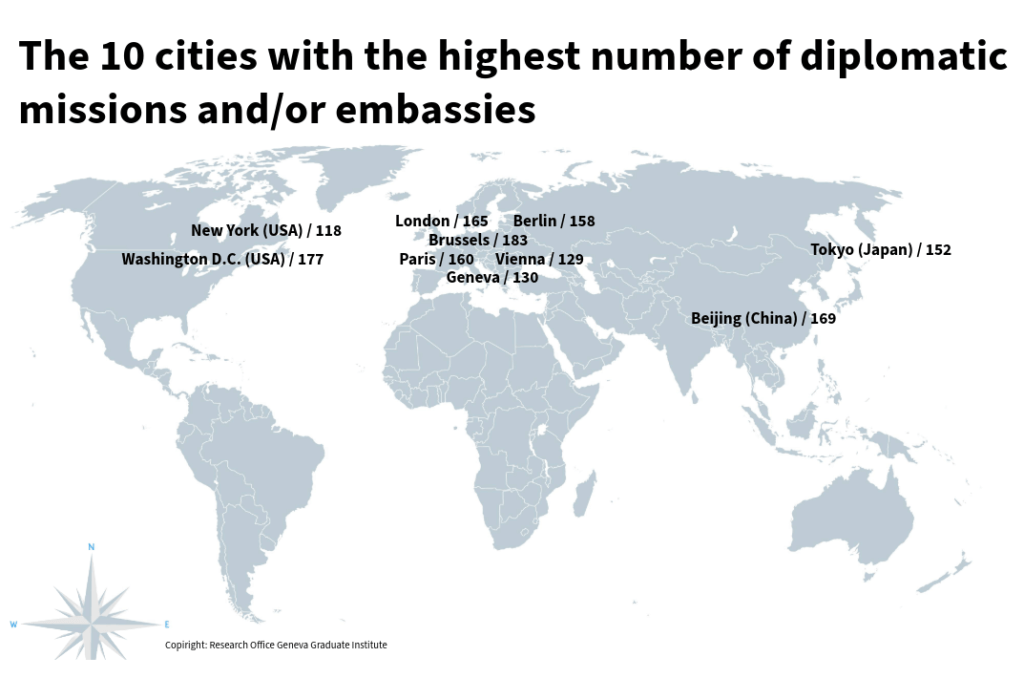

TABLE | The 20 Countries with the Most Diplomatic Missions in the World in 2024

| Country | Total number of posts | Embassies | Consulates | Permanent Missions | Other representations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 274 | 173 | 91 | 8 | 2 |

| USA | 271 | 168 | 83 | 11 | 8 |

| Turkey | 252 | 145 | 93 | 12 | 2 |

| Japan | 251 | 152 | 66 | 10 | 23 |

| France | 249 | 158 | 72 | 18 | 1 |

| Russia | 230 | 143 | 74 | 10 | 3 |

| UK | 225 | 156 | 51 | 11 | 7 |

| Germany | 217 | 148 | 56 | 11 | 2 |

| Italy | 206 | 124 | 74 | 8 | 0 |

| Brazil | 205 | 135 | 58 | 12 | 2 |

| India | 201 | 142 | 50 | 5 | 4 |

| Spain | 190 | 114 | 65 | 10 | 1 |

| South Korea | 187 | 114 | 60 | 5 | 8 |

| Mexico | 161 | 80 | 71 | 8 | 2 |

| Canada | 157 | 98 | 38 | 11 | 10 |

| Argentina | 150 | 87 | 54 | 7 | 2 |

| Netherlands | 149 | 106 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| Switzerland | 141 | 102 | 30 | 7 | 2 |

| Hungry | 140 | 87 | 43 | 7 | 3 |

| Poland | 135 | 91 | 33 | 9 | 2 |

All data taken from the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index 2024.

BOX 1 | Diplomatic Realism

Diplomatic realism, often simply referred to as realism, is a theory of international relations that emphasises the competitive and conflictual nature of relations between States. Here are some key principles of diplomatic realism:

- International anarchy: The international system is anarchic, meaning that there is no higher authority to regulate relations between States. States must therefore rely on their own means to ensure their security and interests.

- State sovereignty: States are the main actors in international relations. They are sovereign and act rationally to maximise their security and power.

- Power and national Interests: States seek to maximise their relative power in relation to other states. Power can be measured in terms of capabilities — military, economic, technological, etc. National interests, often defined in terms of security, survival and prosperity, guide the actions of States.

- Balance of power: States form alliances and adopt strategies to maintain a balance of power, thus preventing a single State or coalition of States from becoming too powerful and threatening their security.

- Inevitable conflict: Realists consider conflict to be an inevitable feature of international relations. States are in constant competition for resources, territory and influence, which can lead to conflict and war.

- Pessimism about cooperation: Realists are sceptical about the possibility of lasting international cooperation. They see international institutions and agreements as tools that States use to promote their national interests rather than as means of genuine cooperation.

Diplomatic realism has been influenced by thinkers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Hobbes, and more recently by modern theorists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz. This theory provides a framework for understanding the behaviour of States in a world where security and survival are of paramount concern. This realist theory is one of the analytical frameworks for international relations, in addition to liberalism and constructivism. They all have in common that they are rooted in Western philosophy.

Source: David Ho, “Les théories chinoises des relations internationales: une brève introduction”, La Revue d’histoire militaire, 4 April 2024.

BOX 2 | The New Diplomacy

“New diplomacy” refers to an evolution in traditional diplomatic practices, marked by the emergence of new actors, new means of communication and new issues. It is a concept that has emerged in response to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, marked by globalisation and the growing interdependence of states. It contrasts with traditional diplomacy, which is state-based, secret and bilateral, embodied by foreign ministries and embassies.

- Expansion of diplomatic actors: While traditional diplomacy was monopolised by states, new diplomacy involves multiple actors. It includes non-governmental organisations (NGOs), multinational companies, local authorities (cities, regions), international organisations (UN, WTO, EU…), citizens and social movements.

- Transformation of tools and channels: Digital tools have profoundly changed diplomatic practices. Public diplomacy and “twiplomacy” (diplomacy via X and other networks) enable direct communication between diplomats and the public.

- Broadening of themes: The new diplomacy addresses complex global issues such as climate change, global health, human rights, migration, digital governance and gender equality. For instance, the climate negotiations at COP26 involved not only states, but also NGOs, businesses, indigenous peoples and young activists such as Greta Thunberg.

- Collaborative and multi-level approaches: Diplomacy is no longer just vertical (between governments), but also horizontal, via cooperation networks between cities (e.g. C40 Cities), universities and civil society.

- More transparent and responsive diplomacy. Negotiations are increasingly subject to pressure from public opinion, the media and real-time communication dynamics. This makes diplomacy more visible, but also more vulnerable to polarisation or communication effects.

In summary, new diplomacy is a more holistic and integrated approach to international relations that recognises the complexity and interdependence of the modern world. It seeks to address global challenges through cooperation, engagement with a diversity of actors, and the use of new tools and technologies.

BOX 3 | Figures on International Geneva and Impact of US Cuts on United Nations Funding

- 43 international organisations in the Lake Geneva area (38 in Geneva, 46 in total in Switzerland)

- 183 States represented

- About 750 non-governmental organisations (NGOs)

- More than 4,000 visits per year of heads of state and government, ministers and other dignitaries

- In 2024, 36,460 people were employed in IOs, NGOs and permanent missions:

- 28,962 people employed in IOs

- 4,062 people employed in permanent missions

- 3,436 people employed in NGOs

- In 2024, the United States funded 22% of the UN regular budget, more than China (15.25%) and Japan (8.03%). But in 2025, it significantly reduced its financial contributions:

- Reduction of more than 80% for the UN regular budget, affecting more than 40 international organisations, including UNESCO and the World Health Organisation (WHO)

- Suspension of USD 377 million for UNFPA, the UN agency for reproductive health, impacting 48 programmes in crisis areas such as Gaza, Sudan and Ukraine

- Cuts of USD 160 million for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), jeopardising global efforts to monitor avian influenza

- Estimated reduction of 30% for the International Organization for Migration (IOM), affecting more than 6,000 employees worldwide.

- To prevent staff layoffs due to the US funding freeze, the Canton of Geneva has allocated CHF 10 million and the City of Geneva CHF 2 million to support local NGOs.

Sources: République et canton de Genève, “Statistiques cantonales”. République et canton de Genève, Genève internationale, “Facts and Figures”. Confédération suisse, “Facts and Figures about International Geneva”. Better World Campaign, “Proposed FY25 Spending Bill for Foreign Operations Would Gut U.S. Global Standing”, 6 April 2025. United Nations Office at Geneva, “US Funding Cuts Confirmed, Ending Lifesaving Support for Women and Girls”, 27 February 2025. Susannah Savage and Michael Peel, “American Farmers Raise Alarm As US Cuts Funds for UN Bird Flu Fight”, Financial Times, 9 May 2025. International Organization for Migration, “Update on IOM Operations amid Budget Cuts ”, 18 March 2025. US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, United Nations Issues: US Funding to the UN System, by Luisa Blanchfield, IF10354, 9 April 2024. Frédéric Julliard, “Genève souffle le chaud et le froid sur les ONG”, Le Temps, 17 February 2025. Fanny Scuderi, “La ville de Genève alloue 2 millions de francs d’aide aux ONG”, 13 March 2025.

VIDEO | Former US Representative to the UN Amb. Sheba Crocker on Her Three Years in International Geneva

U.S. Mission Geneva

VIDEO | Diplomacy Today, with Stephan Klement, EU Diplomat and Special Adviser on Iran Nuclear Issue

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | La diplomatie de la restitution des œuvres d’art avec Amb. Angelo Dan

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute