“A Perverse Version of the Nobel Prize”: The Symbolic Power of the Label of “Genocide”

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-phr4-z506Mahmood Mamdani once described the term “genocide” as “a perverse version of the Nobel Prize”, by which he meant that “genocide has become a label to be stuck on your worst enemy”. Comparing genocide with the Nobel prize — even with the perverse version of the latter — may not seem a felicitous move. But it has the merit of stressing some key questions that are often overlooked in public discussions. What difference does it make to call a mass crime a genocide? Why do accusations of genocide typically trigger intense contestations of the kind that are not seen in the case of other mass crimes? Why does genocide receive a special treatment in international legal discourse, often being described as “the crime of crimes”, “the crime of all crimes” or “an odious scourge”, even though international law does not rank mass crimes according to their level of atrocity or otherwise distinguish them in terms of gravity?

It is sometimes argued that the response lies in the doctrine of “the responsibility to protect”. The alleged culprit and its possible allies among powerful countries are said to be allergic to the label of genocide because of the latter’s potential to trigger the mechanisms of the responsibility to protect. But the doctrine of the responsibility to protect is not limited to genocide (its official articulation refers to “the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity”) and it is a largely toothless doctrine adding nothing meaningful to the mechanisms already existing under the Charter of the United Nations. Genocide is also not distinguishable from war crimes and crimes against humanity as a ground for universal jurisdiction, which gives every country the possibility of criminal prosecution even in the absence of territorial or nationality-related connections.

A more plausible explanation can be found in the symbolic power of the label of genocide. One can even ask, as the philosopher Paul Boghossian does, “whether it’s true that targeting a particular group really is morally worse than simply killing large numbers of people”. But where this symbolic power comes from is not immediately obvious. According to the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, “genocide” means a series of specifically enumerated harmful acts “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”. It is not clear why only a national, ethnical, racial or religious group can be the victim of a genocide and not, for instance, a political or cultural group.One can even ask, as the philosopher Paul Boghossian does, “whether it’s true that targeting a particular group really is morally worse than simply killing large numbers of people”.

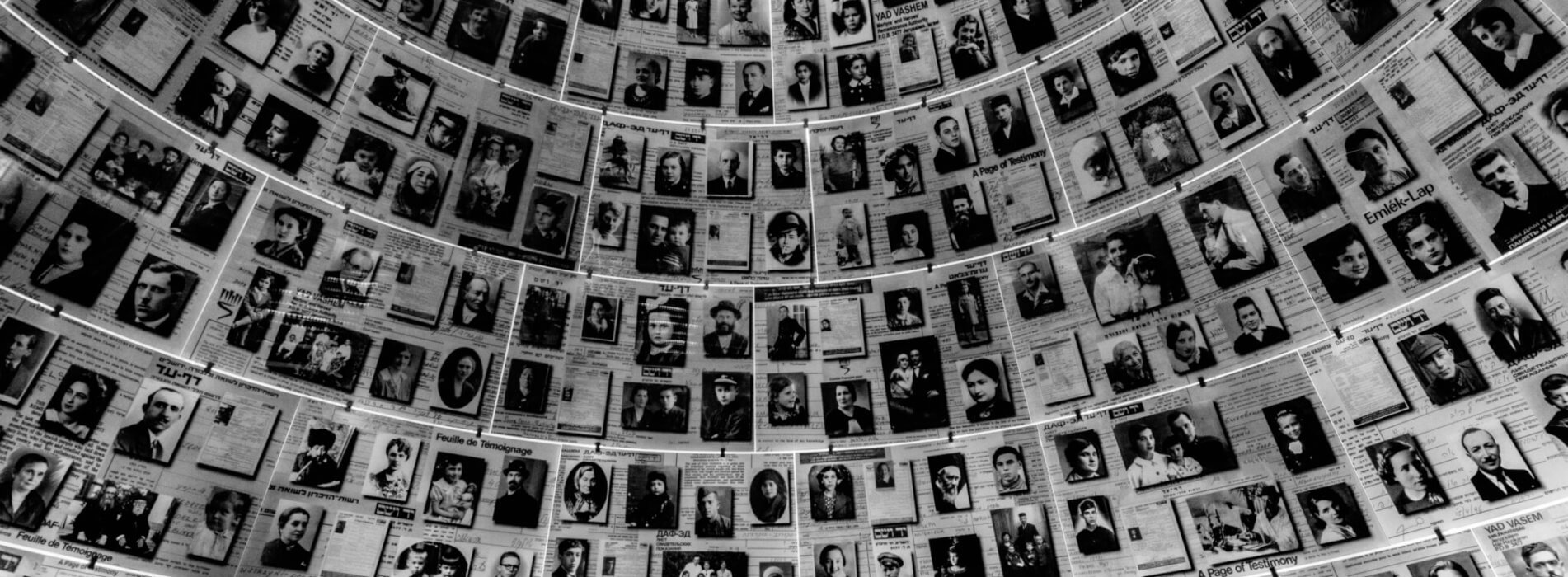

Much of the symbolic power of the label of genocide most probably lies in what could be described (in George Lakoff’s words) as the “idealised cognitive model” that we typically associate with genocide. For most of us, that model is the Holocaust; not because, as a lawyer acting as a council for a government appearing before the International Court of Justice recently stated rather inelegantly, any group has trademark rights over the label of “genocide”, but simply because the very concept of genocide emerged in response to the Holocaust. It is true that, as Jean-Paul Sartre pointed out, unlike the word “genocide”, “the thing itself is as old as humanity”. The United Nations Genocide Convention acknowledges this in its preamble, stating that “at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity”. But the concept did not exist until the Polish jurist Raphael Lemkin coined it in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe published in 1944.

The Holocaust is also arguably the most widely known genocide. It would be hard today to come across any decently educated person who has not read a book or has not seen a film about the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany against the Jews. The magnitude of the horrors that the Holocaust represents — starting with the sheer number of its victims in a single ethnoreligious group (six million) — defies imagination and stands for quintessential representation of human evil. It is thus no wonder that any serious accusation of genocide carries with it a serious potential for stigmatisation, at the very least in global public opinion.

It is also the symbolic power of “genocide” that explains the reluctance of many — not only in Israel, but in the official circles of numerous Western countries as well — to even consider the possibility that Israel — a country whose origin and history are so inextricably linked with genocide — has committed genocide in Gaza with its indiscriminate killing and starvation inflicted upon the population of Gaza, as the UN-mandated Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory has recently concluded. The then French Foreign Affairs Minister probably spoke for many Western countries when infamously stating in January 2024 that “to accuse the Jewish state of genocide is to cross a moral threshold”.

The growing consensus that many Israeli actions in Gaza amount to a genocide shows that when the credibility gap between a symbol and the facts is too big, the facts have the last word. But although they exercise a powerful hold over our imagination, symbols do not have the power to erase reality. The growing consensus that many Israeli actions in Gaza amount to a genocide shows that when the credibility gap between a symbol and the facts is too big, the facts have the last word.

Electronic reference

Zarbiyev, Fuad. “‘A Perverse Version of the Nobel Prize’: The Symbolic Power of the Label of ‘Genocide’.” Global Challenges, no. 18, December 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/18/a-perverse-version-of-the-nobel-prize-the-symbolic-power-of-the-label-of-genocide. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-phr4-z506.Dossier produced by the Geneva Graduate Institute’s Research Office.

BOX 1 | Definition of the Concept of Genocide

The concept of genocide was defined legally for the first time in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948. According to Article II of this Convention, genocide means

“any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

a) Killing members of the group;

b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

To be noted: “Measures intended to prevent births’”, such as forced sterilisation, can therefore be legally considered an act constituting genocide — provided that the deliberate intention to destroy a targeted group can be proven. It is this dimension of genocidal intent that makes it difficult to legally recognise forced sterilisation as genocide, even if it technically meets the criteria defined by the Convention (Case Matrix Network)

Source: United Nations, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

GRAND ENTRETIEN | Genocide, with Paola Gaeta

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | Past, Present and Future of Genocide. Annyssa Bellal

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | Logiques néocoloniales, responsabilité française et génocide rwandais. J.-F. Bayart

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | Israel’s Weaponisation of Water in Gaza

BOX 2 | Genocides: UN Recognition and Historical Consensus

- The Holocaust (Shoah) (1941–1945), recognised via UN General Assembly Resolution 96 (I) in 1946, which led to the 1948 Genocide Convention

- Genocide against the Tutsi (Rwanda, 1994), recognised by UN Security Council Resolutions 955 and 978 (1994); International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) established

- Srebrenica Genocide (Bosnia, 1995), recognised by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice (2007 ruling)

- Herero and Nama Genocide (German Southwest Africa, 1904–1908), recognised by Germany (2021)

- Assyrian and Pontic Greek Genocides (1914–1923), recognised by some national parliaments

- Armenian Genocide (1915–1917), recognised by many national parliaments (France, Germany, Canada, etc.)

- Holodomor (Ukraine famine) (1932–1933), recognised by Ukraine and several other countries

- Cambodian Genocide (1975–1979), recognised by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC)

- Anfal Campaign against Kurds (Iraq, 1988), recognised by several national courts

- Darfur Genocide (Sudan, 2003–present), prosecuted by the International Criminal Court; UN uses “crimes against humanity”

- Destruction of Indigenous Peoples of the Americas (16th–20th centuries), considered genocidal by many historians

- Cultural genocide of Indigenous Peoples (Canada, Australia, etc.), recognised as “cultural genocide” or “systemic assimilation”, not as genocide in the UN’s legal sense

- Massacre of the Aché People (Paraguay, 1960s–1970s), documented by NGOs and historians

- Gaza / Occupied Palestinian Territories, UN experts describe acts as “genocidal”

- Rohingya in Myanmar, UN Independent Investigative Mechanism; case before the International Court of Justice

- Tigray (Ethiopia), joint UN–Ethiopian Human Rights Commission investigations

- Ukraine, UN Commission of Inquiry examining possible incitement to genocide

- Uyghurs in China (Xinjiang), ongoing UN human rights investigations

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChapGPT, CoPilot, UN (United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 96 (I), “The Crime of Genocide”, 11 December 1946, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/209873; Resolution A/RES/60/7, “Holocaust Remembrance”, 21 November 2005, https://docs.un.org/a/res/60/7; Resolution A/RES/78/282, “International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica”, 23 May 2024, https://docs.un.org/A/Res/78/282; “UN Resolutions Relevant to Genocide Prevention”, https://www.un.org/en/genocide-prevention/SA-prevention-genocide/UN-resolutions; “UN General Assembly Adopts Resolution on Srebrenica Genocide, Designating International Day of Reflection, Commemoration”, press release, 23 May 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2024/ga12601.doc.htm).

BOX 3 | Complaints for Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity

Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity are among the most serious international crimes, as defined by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948), the Geneva Conventions (1949) and their Protocols, and the Rome Statute (1998), which established the International Criminal Court (ICC). They are considered non-prescriptible: complaints can be filed even decades later.

Where can complaints be filed?

– Before the International Criminal Court (ICC)

The ICC can try cases of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of aggression. Cases can be referred to it in three ways: by a state party to the Rome Statute (123 states today), by the ICC Prosecutor, who can take up a case on his own initiative after authorisation by the judges, or by the UN Security Council (even for non-member states, e.g. Darfur, Libya).

Can an individual file a complaint? Yes, but in the form of a communication to the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP). The ICC is not a direct complaint jurisdiction like a national court: an individual can submit a case, but only the Prosecutor decides whether to open an investigation.

There are significant limitations to the ICC. It only tries individuals, not states. It only has jurisdiction if the crime took place on the territory of a state party, if the perpetrator is a national of a state party, or if the Security Council refers the case. Finally, some geopolitically important states do not recognise the ICC (the United States, Russia, China, Israel, etc.).

– Before a national court

Many states now allow complaints for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, even if the crimes were committed abroad and by foreigners. This is known as universal jurisdiction. Examples of countries that regularly use it include France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Canada (partially) and Spain (more limited since 2014). The specific conditions vary from country to country, but generally require the presence of the suspect on the territory, a complaint from victims or NGOs, and national prosecutors who open investigations themselves. This mechanism is being used increasingly frequently (trials of Syrian torturers, Rwandan soldiers, etc.).

– Before the International Court of Justice (ICJ)

The ICJ does not judge individuals, but can be called upon in disputes between states, particularly for accusations of genocide (e.g. Gambia v. Myanmar; South Africa v. Israel), violations of the Geneva Conventions, and disputes over the interpretation of international treaties. It is important to note that private individuals cannot bring cases before the ICJ. Only states can do so.

The courts for Rwanda and Kosovo

Complaints cannot be brought before these courts by individuals. They are ad hoc international criminal tribunals with jurisdiction to try individuals responsible for serious crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes).

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established in 1994 by the UN Security Council to try those responsible for the genocide of the Tutsis and crimes against humanity committed in Rwanda.

The Special Tribunal for Kosovo (Kosovo Specialist Chambers) was established in 2015, based in The Hague, to try crimes committed by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) between 1998 and 2000.

There may be indirect interactions with the ICJ, for example when the ICJ examines the responsibility of a state for acts that also constitute crimes tried by a criminal tribunal (e.g. the Bosnia v. Serbia case on the Srebrenica genocide).

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChapGPT, CoPilot, UN.

BOX 4 | The Obligation to Act in the Face of Genocide

The 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention imposes a legal obligation on all signatory states to prevent and punish genocide. This obligation is known as erga omnes, which means that it is owed to the entire international community and not only to the state where the crime is taking place. Thus, even a country not directly involved must intervene to the extent of its capabilities, in particular through diplomatic, economic, legal or humanitarian means. In concrete terms, this may take the form of economic sanctions, diplomatic pressure, suspension of arms sales, humanitarian aid, cooperation with the courts, or speaking out at the UN.

This obligation applies to all states parties (153 today), regardless of their geography or political interests. It does not depend on the filing of a complaint with the International Court of Justice (ICJ): the complaint is simply one legal mechanism among others, but the obligation to act exists outside of any proceedings.

Finally, it is an obligation of means, not of results: powerful states must do more, while less influential states may limit themselves to actions proportionate to their capabilities.

NB. A State may only intervene militarily to stop genocide if it has authorisation from the Security Council or a recognised collective mandate. No State may invoke genocide to justify a military attack on its own. For example, Russia attempted to justify its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 by invoking the prevention of genocide, but the ICJ rejected this argument.

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChatGPT, CoPilot, UN.

BOX 5 | Is the Holodomor Recognised as a Genocide?

The legal status of the Holodomor — the Ukrainian famine of 1932–33 — as a genocide remains a matter of international debate. According to the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention, genocide refers to acts committed “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”.

Scholars and the Ukrainian state argue that the famine fits this definition, citing Soviet policies that intentionally targeted the Ukrainian peasantry, culture, and political autonomy. Evidence includes:

- Forced grain requisitions far beyond subsistence levels

- Border closures preventing peasants from fleeing famine zones

- Suppression of Ukrainian language, institutions, and elites

- A disproportionate death toll among Ukrainians compared to other Soviet republics

As of 2025, more than 30 countries — including Canada, Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic states, and recently Germany — officially recognise the Holodomor as a genocide. However, neither the United Nations nor the International Criminal Court has issued a binding legal ruling on the matter, and Russia maintains that the famine was a broader Soviet tragedy, not a targeted ethnic crime.

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChapGPT, CoPilot, UN.