Naming Extermination: History of a Vocabulary

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-y3p3-zw97From the Nuremberg Trials (1945–1946) onward, and with the gradual opening of archives, historical research has traced the terminology employed by the Nazi apparatus to describe the deportation and subsequent extermination of Jews under the Third Reich. The noun phrase “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” (Endlösung der Judenfrage) became an administrative designation following the Wannsee Conference (January 1942), which systematised and coordinated its execution. Historians such as Saul Friedländer use this phrase with great caution — often in quotation marks or italics — because it belongs to a bureaucratic lexicon saturated with euphemisms and embedded in the perpetrators’ coded language, which tends to obscure both the nature and scope of the extermination project.

This raises a persistent dilemma: should one coin a neologism at the risk of essentialising the event, or instead metaphorically employ a preexisting term, while confronting the enduring difficulty of naming the unnameable?

During the war and immediately afterward, the Hebrew word hurban (hurbn in Yiddish), used notably by ghetto diarists, served to denote the destruction of European Jewry. In Jewish tradition, this term refers first to the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem (586 BCE and 70 CE), and by extension, to expulsions, persecutions, and collective massacres throughout Jewish history. Central within Ashkenazi cultural and religious circles, it has remained marginal in Western languages — partly because of its strong scriptural resonance and its association with a linear vision of Jewish history as a chain of catastrophes, but above all due to the near disappearance of Yiddish speakers after the war.

The first attempt at legal qualification occurred during the Nuremberg Trials, where the defendants were charged with conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, the latter defined in the London Charter of August 1945. In 1944, the Polish-Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin (1900–1959) coined the term “genocide” to furnish international law with an instrument capable of addressing mass crimes. The concept gained normative recognition in 1948 with the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Its universalist scope makes it a crucial analytical category; yet its typological abstraction has often struggled to convey the singularity of the annihilation of the Jews.

The term “holocaust”, used with a lowercase “h”, derives from the Greek holókaustos, originally referring to a ritual sacrifice in which an animal is entirely consumed by fire in honour of a deity. Even before World War II, the term had already been used in several European languages to describe collective massacres or massive destruction. When capitalised, its adoption to designate the Nazi persecution and extermination of Jews retains a sacrificial undertone, implying an offering or transcendent purpose, which renders it problematic. Despite such reservations, the global impact of the 1978 television miniseries Holocaust, directed by Marvin Chomsky, consolidated its dominance in the English-speaking world, where it remains the most common designation.

It was within a broader reconfiguration of memory regimes — marked notably by the emergence of the survivor figure after the Eichmann trial (1961) — that the term Shoah came to prominence. Derived from biblical Hebrew, where it denotes catastrophe, calamity, or disaster caused by God, nature, or human agency, Shoah was already used in the 1930s, notably in the Jewish press of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine). However, it had not yet acquired a fixed or general meaning as a term for the persecution and extermination of Jews. The semantic shift began during World War II and was consolidated in the early 1950s with the establishment of Yom HaShoah (“Shoah Day”) in 1951 and the creation of the Yad Vashem memorial in 1953. According to Francine Kaufmann, “the theological meaning and biblical reference are no longer perceptible in contemporary Hebrew”, allowing the term to gradually enter common language and supplant “Holocaust” in Hebrew and French usage. She adds that the word avoids both the sacrificial dimension implied by “Holocaust” and the notion of historical recurrence embedded in hurban, establishing instead a mode of naming that singularises the event and anchors it in a specific moral and historical register.

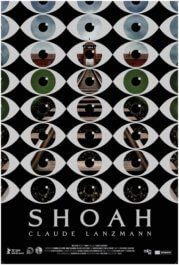

Its international diffusion — for example, its adoption by the Vatican in 1998 — accompanied the growing recognition of survival testimony as a central mode of historical knowledge. Claude Lanzmann’s monumental film Shoah (1985) played a decisive role in this transformation. By rejecting archival footage and elevating survivor voices as the foundation of the narrative, the film performed a powerful epistemic act. It inscribed the term Shoah in French public discourse and, more broadly, in the global memorial lexicon. This lexical shift mirrored an epistemological turn. Testimony, long regarded as secondary evidence for historians, came to be understood as a primary source of meaning. The survivor witness ceased to be merely a victim and became an agent of interpretation. Testimony thus became not only a vehicle of memory but a key to the intelligibility of history itself — at the intersection of lived experience, ethical authority and collective recognition. In this sense, the word Shoah acquired, beyond terminology, a performative dimension binding together memory, ethics and historical understanding.Yet “Shoah” does not displace other designations and, like them, carries political implications.

Yet Shoah does not displace other designations and, like them, carries political implications. Without replacing the legal category of genocide, it emphasises the existential and memorial dimensions of the event. Whereas international law seeks universality, the term Shoah affirms the event’s incommensurability and foregrounds a mode of naming rooted in the victims’ experience. More than a historical designation, Shoah constitutes a symbolic space of recognition and transcends the normative framework of genocide. In this sense, it crystallises a collective endeavour to name what defies language and elevates survivor testimony as a major hermeneutic key to understanding the extermination of the Jews.

Electronic reference

Neury, Laurent. “Naming Extermination: History of a Vocabulary.” Global Challenges, no. 18, December 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/18/naming-extermination-history-of-a-vocabulary. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-y3p3-zw97.Dossier produced by the Geneva Graduate Institute’s Research Office.

BOX 1 | Definition of the Concept of Genocide

The concept of genocide was defined legally for the first time in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948. According to Article II of this Convention, genocide means

“any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

a) Killing members of the group;

b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

To be noted: “Measures intended to prevent births’”, such as forced sterilisation, can therefore be legally considered an act constituting genocide — provided that the deliberate intention to destroy a targeted group can be proven. It is this dimension of genocidal intent that makes it difficult to legally recognise forced sterilisation as genocide, even if it technically meets the criteria defined by the Convention (Case Matrix Network)

Source: United Nations, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

GRAND ENTRETIEN | Genocide, with Paola Gaeta

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | Past, Present and Future of Genocide. Annyssa Bellal

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | Logiques néocoloniales, responsabilité française et génocide rwandais. J.-F. Bayart

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST | Israel’s Weaponisation of Water in Gaza

BOX 2 | Genocides: UN Recognition and Historical Consensus

- The Holocaust (Shoah) (1941–1945), recognised via UN General Assembly Resolution 96 (I) in 1946, which led to the 1948 Genocide Convention

- Genocide against the Tutsi (Rwanda, 1994), recognised by UN Security Council Resolutions 955 and 978 (1994); International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) established

- Srebrenica Genocide (Bosnia, 1995), recognised by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice (2007 ruling)

- Herero and Nama Genocide (German Southwest Africa, 1904–1908), recognised by Germany (2021)

- Assyrian and Pontic Greek Genocides (1914–1923), recognised by some national parliaments

- Armenian Genocide (1915–1917), recognised by many national parliaments (France, Germany, Canada, etc.)

- Holodomor (Ukraine famine) (1932–1933), recognised by Ukraine and several other countries

- Cambodian Genocide (1975–1979), recognised by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC)

- Anfal Campaign against Kurds (Iraq, 1988), recognised by several national courts

- Darfur Genocide (Sudan, 2003–present), prosecuted by the International Criminal Court; UN uses “crimes against humanity”

- Destruction of Indigenous Peoples of the Americas (16th–20th centuries), considered genocidal by many historians

- Cultural genocide of Indigenous Peoples (Canada, Australia, etc.), recognised as “cultural genocide” or “systemic assimilation”, not as genocide in the UN’s legal sense

- Massacre of the Aché People (Paraguay, 1960s–1970s), documented by NGOs and historians

- Gaza / Occupied Palestinian Territories, UN experts describe acts as “genocidal”

- Rohingya in Myanmar, UN Independent Investigative Mechanism; case before the International Court of Justice

- Tigray (Ethiopia), joint UN–Ethiopian Human Rights Commission investigations

- Ukraine, UN Commission of Inquiry examining possible incitement to genocide

- Uyghurs in China (Xinjiang), ongoing UN human rights investigations

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChapGPT, CoPilot, UN (United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 96 (I), “The Crime of Genocide”, 11 December 1946, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/209873; Resolution A/RES/60/7, “Holocaust Remembrance”, 21 November 2005, https://docs.un.org/a/res/60/7; Resolution A/RES/78/282, “International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica”, 23 May 2024, https://docs.un.org/A/Res/78/282; “UN Resolutions Relevant to Genocide Prevention”, https://www.un.org/en/genocide-prevention/SA-prevention-genocide/UN-resolutions; “UN General Assembly Adopts Resolution on Srebrenica Genocide, Designating International Day of Reflection, Commemoration”, press release, 23 May 2024, https://press.un.org/en/2024/ga12601.doc.htm).

BOX 3 | Complaints for Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity

Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity are among the most serious international crimes, as defined by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948), the Geneva Conventions (1949) and their Protocols, and the Rome Statute (1998), which established the International Criminal Court (ICC). They are considered non-prescriptible: complaints can be filed even decades later.

Where can complaints be filed?

– Before the International Criminal Court (ICC)

The ICC can try cases of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of aggression. Cases can be referred to it in three ways: by a state party to the Rome Statute (123 states today), by the ICC Prosecutor, who can take up a case on his own initiative after authorisation by the judges, or by the UN Security Council (even for non-member states, e.g. Darfur, Libya).

Can an individual file a complaint? Yes, but in the form of a communication to the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP). The ICC is not a direct complaint jurisdiction like a national court: an individual can submit a case, but only the Prosecutor decides whether to open an investigation.

There are significant limitations to the ICC. It only tries individuals, not states. It only has jurisdiction if the crime took place on the territory of a state party, if the perpetrator is a national of a state party, or if the Security Council refers the case. Finally, some geopolitically important states do not recognise the ICC (the United States, Russia, China, Israel, etc.).

– Before a national court

Many states now allow complaints for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, even if the crimes were committed abroad and by foreigners. This is known as universal jurisdiction. Examples of countries that regularly use it include France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Canada (partially) and Spain (more limited since 2014). The specific conditions vary from country to country, but generally require the presence of the suspect on the territory, a complaint from victims or NGOs, and national prosecutors who open investigations themselves. This mechanism is being used increasingly frequently (trials of Syrian torturers, Rwandan soldiers, etc.).

– Before the International Court of Justice (ICJ)

The ICJ does not judge individuals, but can be called upon in disputes between states, particularly for accusations of genocide (e.g. Gambia v. Myanmar; South Africa v. Israel), violations of the Geneva Conventions, and disputes over the interpretation of international treaties. It is important to note that private individuals cannot bring cases before the ICJ. Only states can do so.

The courts for Rwanda and Kosovo

Complaints cannot be brought before these courts by individuals. They are ad hoc international criminal tribunals with jurisdiction to try individuals responsible for serious crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes).

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established in 1994 by the UN Security Council to try those responsible for the genocide of the Tutsis and crimes against humanity committed in Rwanda.

The Special Tribunal for Kosovo (Kosovo Specialist Chambers) was established in 2015, based in The Hague, to try crimes committed by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) between 1998 and 2000.

There may be indirect interactions with the ICJ, for example when the ICJ examines the responsibility of a state for acts that also constitute crimes tried by a criminal tribunal (e.g. the Bosnia v. Serbia case on the Srebrenica genocide).

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChapGPT, CoPilot, UN.

BOX 4 | The Obligation to Act in the Face of Genocide

The 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention imposes a legal obligation on all signatory states to prevent and punish genocide. This obligation is known as erga omnes, which means that it is owed to the entire international community and not only to the state where the crime is taking place. Thus, even a country not directly involved must intervene to the extent of its capabilities, in particular through diplomatic, economic, legal or humanitarian means. In concrete terms, this may take the form of economic sanctions, diplomatic pressure, suspension of arms sales, humanitarian aid, cooperation with the courts, or speaking out at the UN.

This obligation applies to all states parties (153 today), regardless of their geography or political interests. It does not depend on the filing of a complaint with the International Court of Justice (ICJ): the complaint is simply one legal mechanism among others, but the obligation to act exists outside of any proceedings.

Finally, it is an obligation of means, not of results: powerful states must do more, while less influential states may limit themselves to actions proportionate to their capabilities.

NB. A State may only intervene militarily to stop genocide if it has authorisation from the Security Council or a recognised collective mandate. No State may invoke genocide to justify a military attack on its own. For example, Russia attempted to justify its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 by invoking the prevention of genocide, but the ICJ rejected this argument.

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChatGPT, CoPilot, UN.

BOX 5 | Is the Holodomor Recognised as a Genocide?

The legal status of the Holodomor — the Ukrainian famine of 1932–33 — as a genocide remains a matter of international debate. According to the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention, genocide refers to acts committed “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”.

Scholars and the Ukrainian state argue that the famine fits this definition, citing Soviet policies that intentionally targeted the Ukrainian peasantry, culture, and political autonomy. Evidence includes:

- Forced grain requisitions far beyond subsistence levels

- Border closures preventing peasants from fleeing famine zones

- Suppression of Ukrainian language, institutions, and elites

- A disproportionate death toll among Ukrainians compared to other Soviet republics

As of 2025, more than 30 countries — including Canada, Ukraine, Poland, the Baltic states, and recently Germany — officially recognise the Holodomor as a genocide. However, neither the United Nations nor the International Criminal Court has issued a binding legal ruling on the matter, and Russia maintains that the famine was a broader Soviet tragedy, not a targeted ethnic crime.

Sources: Marc Galvin, Wikipedia, ChapGPT, CoPilot, UN.