Populism 4.0 and Decent Digiwork

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-1kdk-ca84With the need for global cooperation and technocratic expert-driven responses, all in response to an unprecedented health crisis, several analyses were quick to conclude that Covid-19 would “kill” populism. But it may be premature to assume that this crisis will eradicate populism altogether, as many speculate. A number of key developments in the post-Covid-19 digital era may indeed point to a strong “comeback scenario” for populism to which we need to be alert.

THE GIG ECONOMY DIVIDE

As a result of the pandemic, companies will become increasingly eager to lower labour costs by outsourcing work to flexi-digiworkers in the gig economy As a result of the pandemic, companies will become increasingly eager to lower labour costs by outsourcing work to flexi-digiworkers in the gig economy. This development may further accelerate a divide which already existed before the pandemic – that between well-paid, high-end freelance workers (e.g. digital marketing specialists or management consultants) and lower-paid flexi-digiworkers often linked to digital platforms, such as ride-hailing and food delivery. Those low-paid gig economy workers have been hugely affected by the Covid-19 crisis worldwide and the “anaemic” coverage of social protection. Addressing the gig economy divide is crucial, as it can potentially intensify grievances which may generate anger and political discontent. It is no accident that people that work at the margins of the new gig economy are those that vote for choices supported by populist forces.

LOCKDOWN WINNERS AND LOSERS

According to the latest ILO data, nearly half of the global workforce is at risk of losing livelihoods and more than 436 million enterprises face serious disruption following the “lockdown”. That translates into the loss of 305 million jobs.

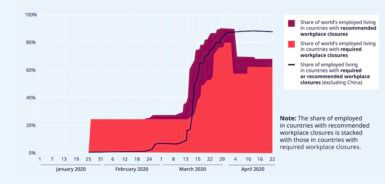

Figure 1. Impacts of recommended and required workplace closures on employment in countries applying such closures (as of 22 April 2020)

Figure 1. Impacts of recommended and required workplace closures on employment in countries applying such closures (as of 22 April 2020)These impacts are uneven as lockdowns have generated new socio-economic divides in a whole series of countries and regions: between workers “Inside and With” (in safe jobs, with the ability to telework during the lockdowns and the main recipients of governments’ recent financial aid packages) and those “Outside and Without” (non-standard, informal and atypical workers including the low-paid flexi-digiworkers in the gig economy, who during the lockdowns lost their jobs and income and were left without adequate protection).

the pandemic has intensified many of the failures of the “old normal” of the previous global crisis Those “Outside and Without” have found themselves heavily impacted, as the pandemic has intensified many of the failures of the “old normal” of the previous global crisis. Inequality has been growing since then, affecting more than two-thirds of the globe and reaching unprecedented levels. As the crisis unfolds, only one in five unemployed people globally can count on unemployment benefits, while a striking 55 percent of the world’s population have no social protection coverage whatsoever.

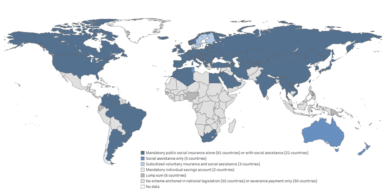

Figure 2. Unemployment protection schemes, by type of scheme.

Figure 2. Unemployment protection schemes, by type of scheme.The persistence of lockdown divides and inequalities will strongly depend on the impact of countries’ rising debt burdens in the recovery phase, in conjunction with the impact of labour market disruptions defined by the “Fourth Industrial Revolution”. Predictions show that even if automation and digitalisation will not permanently destroy jobs, certain groups of workers will still face serious dislocation and transitions of unemployment as they will need to move to new occupations and sometimes new geographical locations.

POPULISM ON THE DAY AFTER

The degree of tolerance of coronavirus-induced disparities in the post-Covid-19 digital world will be critical.The degree of tolerance of coronavirus-induced disparities in the post-Covid-19 digital world will be critical Albert Hirschman uses the analogy of a traffic jam in a two-lane tunnel to explain how people respond to inequality: people stuck in the left-lane will feel better once they see that a car in the right lane starts to move. This initial gratification is known as the “tunnel effect”. Yet, such gratification will fade rapidly if it becomes apparent that only the cars in the right lane are moving. According to Hirschman, those left out in the process of economic growth may better tolerate increasing inequality if they anticipate that their lot is likely to improve soon. Otherwise, their frustration may breed social unrest.

Hirschman’s analogy provides valuable insights for understanding what may happen in our post-pandemic digital economies the day after, once the tunnel effect is over. If inequalities are not addressed, populists are likely to benefit from the frustration generated by the unequal future of work. A new brand of populism, Populism 4.0, would thrive on the persistent failure to address the vulnerabilities created by the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the added economic inequity generated by the Covid-19 crisis.

The rise of populists in recent years has been driven by a narrative of communities and groups of people permanently left behind by economic and social dislocations. Populism 4.0 could take various forms and shapes. It could link softer or harder anti-tech rhetoric to the various “anti-” narratives that dominated the pre-pandemic era, turning debates on the future of work into emotionally charged battlefields. For instance, drawing linkages with climate change, populist arguments could brand the digital revolution as an elitist hoax, blaming global and national elites for “hyper-digitalisation” and demonising all sorts of technological progress. In Europe, populism 4.0 could evolve differently depending on domestic contexts, but its potential interplay with the complex dynamics of “democracy-demography” could constitute a major challenge. As illustrated by a recent survey, 53 percent of young Europeans (aged 16–29) doubt democracy’s capacity to deliver change (e.g. address climate change), placing greater trust in authoritarian states. This finding is alarming as it coincides with bleak employment prospects for young people in Europe, but also worldwide, that could fuel social unrest: more than one in six young people has been forced to stop working since the Covid-19 crisis began, while more than three-quarters of those in employment were in informal jobs including in the digital gig economy.

These developments send an important message: the complex dynamics of demography, technology and populism unfolding in the post-pandemic era will prove crucial for the future of our democracies. Rather than allowing the future of work to become part of the 2020s populist playbook, we need reforms – now.

WILL WE BUILD A BETTER WORLD AFTER THE PANDEMIC?

In shaping the post-Covid-19 future of work, we must not allow our labour market structures and social policies to weigh unfairly on the most vulnerable citizens. If the structures and policies remain unaffected, there is a very real risk that populists will gain additional strength, mobilising their usual strategies of dividing societies and denigrating opposition voices if they do not conform to their preferred narrative of the “future of work”.

In fighting the pandemic, governments have so far “followed the experts”. However, technical knowledge alone will not resolve the complex issues outlined above; we need both: data and transformative vision. Technical but also “emancipatory” knowledge – in a Habermasian sense, this means self-reflection and critical questioning of the social systems within which we live.

As I write in a recent article, decent digiwork is a vision of full participation in a digital-work future which affords self-respect and dignity, security and equal opportunity, representation and voice. It is about refitting our labour markets, social-protection and welfare systems and making sure everyone has the ability to realise the human right to social security. If the unprecedented fiscal interventions recently announced by governments worldwide are used to close social protection gaps beyond the crisis, and make the vulnerable less vulnerable, we could set the world on a considerably different longer-term trajectory.

Above all, we need to bring social dialogue within the scope of the digital economy and work. The examples of collective and other agreements signed so far by digital platforms and labour unions in several countries in Europe, setting hourly minimum wages, protection in case of dismissal and social security provisions, not only show that social dialogue is flexible enough to accommodate the challenges of tomorrow, but also that innovation is not incompatible with employment protection.

For the digital age, a return to a pre-Covid-19 “normal” is not an option For the digital age, a return to a pre-Covid-19 “normal” is not an option. Only a fairer future of work can make our societies less fragmented and our democracies more resilient, rather than vulnerable, to populism rebranded.

Electronic reference

Mexi, Maria. “Populism 4.0 and Decent Digiwork.” Global Challenges, Special Issue no. 1, June 2020. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/special_1/populism-4-0-and-decent-digiwork. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-1kdk-ca84.The issue has been produced by the Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy in collaboration with the Graduate Institute’s Research Office. It includes contributions from all of the Institute’s research centres and departments.

Confederation billions to save the Swiss economy | PODCAST with Cédric Tille

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Peut-on comparer la grippe espagnole et le Covid-19? VIDÉO avec Davide Rodogno

Graduate Institute, Geneva et Heidi.news

What hope for the environment? PODCAST with Joëlle Noailly

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

PODCAST | The violent consequences of the Covid crisis in India, with Rahul Mehrotra

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

New technological tools: a plus for democracy? PODCAST with Jérome Duberry

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Latin America and the Covid-19 crisis | PODCAST with Yanina Welp

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

An Indonesian democracy at risk | PODCAST with Jean-Luc Maurer

Research Office, Graduate Institute, Geneva

Democracy in coronavirus times | VIDEO with Shalini Randeria and Ivan Krastev

The Graduate Institute, Geneva (Excerpt of the podcast series “In Conversation With“)