Why Art? Exploring the Role of “Art and Social Science” Approaches to the Interdisciplinary Study of Multilateralism

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-j8ne-em46The Geneva Graduate Institute’s Centre for Digital Humanities and Multilateralism (CDHM) resists easy categorisation, not only due to the variety of disciplines of its contributors (computational social scientists, historians, sociologists, anthropologists, archivists, legal scholars and playwrights, to name a few), but also because it is dedicated to building a network that supports research across the humanities, as well as digital innovation and artistic creation, linked by a common source: the digitised archives of multilateralism.

Through core partnerships with the UN Library & Archives Geneva (its recently completed LONTAD project digitised the entire League of Nations archives), and a growing cadre of archivists at other International Organizations (IOs), CDHM is using digital tools to bring to a wider audience the vast social, intellectual and historical value of these archival materials, the legacy of international Geneva, and the myriad dynamics of multilateralism that include diplomacy and cultural exchange. At a time when austerity cuts have affected many of Geneva’s IOs, the Centre is directing precious resources toward pilot projects that showcase the value of “living archives” for researchers, artists and the broader public, connecting artists and researchers with archival treasure troves, and helping them do the research work that is necessary, even for artistic projects, to review and possibly reinvent the meaning and practice of multilateralism in Geneva and beyond.

The question here, “Why art?”, is, of course, as complexly layered as it is pragmatic. Maybe one of the origins for the Centre’s focus on creating cooperation between social scientists, historians and artists lay in the experience of one of its codirectors and co-founders, Grégoire Mallard, when he was invited by Bruno Latour in 2005 to visit the exhibition “Making Things Public” that the French sociologist and philosopher had organized with the artist Peter Weibel. The CDHM mission draws inspiration from Latour’s methodology to achieve multifaceted goals: to produce books and articles, but also websites, exhibitions and other participatory forums where multilateral diplomacy can be experienced in a sensory fashion. But the trademark of the CDHM is bringing together researchers from many disciplines – including the performing arts, design and cinema – to create new media for a broad range of publics; through these projects, members of the public can develop a better understanding of global affairs as they are discussed in multilateral settings. In this context, Bruno Latour himself, and his colleague Frédérique Aït-Touati, understood very well the power of performing arts as a technology creating new mediations between social scientists, environmental experts and diplomats, turning, for instance, the Earth (and the archived visualization of its fate) into an object of deliberation. But there are myriad other ways to achieve this goal, including by producing new digital supports such as visualization technologies developed by computational scientists using semantic analyses, through which the living archives of multilateralism can be turned into a “common” object of reflection and political deliberation.

The CDHM is trying to accomplish its objective not only by launching new websites where the public will be able to interact with and research multilateral debates in multiple IOs (starting with those based in Geneva), but also by turning the media itself into an object of problematization. Indeed, in order to deliver on the promise of US President Woodrow Wilson one century ago – that multilateral negotiations should be public, so that the world’s leading problems are addressed fairly – one also has to create technologies of mediation through which these “publics” from many different parts of the world can first get to know the content of negotiations, and then debate their outcomes. This is done through archival strategies that optimize accessibility and participation, but whose operations on the recorded and archived discourse itself should not be “blackboxed”, or made invisible by their own success – to use a term dear to Bruno Latour.

Twenty years after Latour experimented with exhibitions and performances – and after he created one of the CDHM’s partner institutions, the médialab at Sciences-Po Paris, where CDHM associates like Jean-Philippe Cointet are based – the CDHM is inviting artists and researchers in the field of digital humanities to study and reimagine the world of multilateral diplomacy. This comes at the right moment as multilateral diplomacy increasingly becomes an object of exploration for artists of all kinds. As curator and international policy specialist Hannah Entwisle Chapuisat writes in a report recently commissioned by the CDHM, the Centre can critically respond to the specific needs of different types of researchers, including those of artist researchers, by helping them examine archives in creative and unconventional ways; this cooperation, in turn, can contribute to broader interdisciplinary research and ultimately bring the archives’ content to the public at large. As she notes, some researchers go so far as to argue that the unprecedented complexity of global challenges necessitates artistic research that can “reveal deep, qualitative insights that would otherwise remain obscure to canonical research methodologies”. Other studies find that individual engagement with art and cultural activities prompts increased individual reflexivity and enhanced citizen engagement. Such co-operation, in which the artists’ engagement is not a mere illustration of the conceptualization of the work of academic researchers but is research in and of itself, is at the centre of what the CDHM intends to develop in the future.

The CDHM is inviting artists and researchers in the field of digital humanities to study and reimagine the world of multilateral diplomacy.To date, CDHM has developed a stream of activities engaging with the arts, including exploratory collaborations with artists working on visualizations of diplomatic history, contributions to digital exhibitions of intergovernmental archives, and public talks linking artistic methods with global policy discourse. For the 2025-2026 academic year, CDHM Visiting Fellows dramaturge Caroline Barneaud and documentary theatre artist Stefan Kaegi will lead an artistic residency project for doctoral students on subjective and multilateral approaches to researching the archives of international Geneva that they will complement with personal archives. This is not the first time the two artists have collaborated with the Institute. As part of an ongoing dialogue, the Théâtre de Vidy opened its doors to various MINT classes, in particular, students of the course on human rights and humanitarianism taught by Andrew Clapham and CDHM affiliate Julie Billaud. The students participated in a Latourian three-day performance organized by Nilüfer Koç and Jonas Staal titled New World Embassy: Kurdistan, which questioned the legacy of the Treaty of Lausanne 100 years after it was signed. As for Stefan Kaegi, he participated on 24 May 2023, along with architect Daniel Zamarbide and Anna Leander from the Graduate Institute, in a discussion chaired by Prof. Mallard on Performing Diplomacy, Making Space Public: An Interdisciplinary Discussion Between Architecture, Performing Arts and International Relations. In this talk, architects, designers, performing artists and social scientists reflected on the material infrastructures that empower the public to exchange opinions in local, national or transnational arenas, whether the latter are constructed of hard stone, like the Palais des Nations, or in ephemeral public spaces like those constructed by students of the EPFL School of Architecture near the Place des Nations.

Along these lines, CDHM is also in active discussions with the Geneva University of Art and Design (HEAD-Genève) and the Valais School of Art (EDHEA), inviting their students to “think with” the archives of multilateralism by exploring IO architecture and the archives of architectural realizations in Geneva and beyond – including, for instance, modernist projects like the creation of ECLAC’s headquarters, which the CDHM is currently digitizing along with the archives of its first Director, Raúl Prebisch. Similarly, a team of web designers is working with historians and CDHM affiliates like Pierre-Etienne Bourneuf and Sohnee Harshey to catalogue the locations of IOs, NGOs and permanent missions in Geneva over time, and identify archives that relate not only to funders, donors and city authorities, but also to social protests, as well architects’ involvements in the debates about what multilateralism should look like. It is hoped that this initial conversation will produce various research proposals; here, researchers in the Institute’s more traditional disciplines have an important role to play as experts in identifying archival treasures as the basis for groundbreaking analyses of international politics. But these researchers may also have to be re-trained to think about ways to make their archival work a “common”: a treasure shared with the public rather than buried deep inside the footnotes of their monographs and scientific articles.

Expanding such disciplinary dialogues further, the CDHM will this autumn welcome Swiss film director and screenwriter Jean-Stéphane Bron as a visiting artist-researcher. Creator of documentaries such as Cleveland Versus Wall Street and Le Génie helvétique, Bron recently directed the RTS TV series The Deal, set at a fictional negotiation in Geneva on the Iranian nuclear programme, for which Prof. Mallard served as a scientific advisor for part of production. Working with the CDHM and its partners, Bron now plans a filmed oral history as an exploratory basis for an archive-based film project that will be commensurate in research value to partner IOs and academics in interdisciplinary fields, with opportunities for public dissemination. This material will constitute the preliminary research phase of his new directorial project of fiction on multilateralism, bringing these archival materials to a wide TV audience. To launch this project, the CDHM will host a public masterclass with Bron on 21 November 2025 distinguishing the different modes that unite documentary and fiction, and others that separate them, followed by a screening of The Deal and a panel discussion with Prof. Mallard and journalist Serge Michel.

By engaging with novelists, poets and performers, the CDHM’s founders hope to forge relationships that go beyond established academic disciplines. By engaging with novelists, poets and performers, the CDHM’s founders hope to forge relationships that go beyond established academic disciplines, and to raise new resources from donors to deepen the dialogue necessary to reinvent the multilateralism of the future. To meet the challenges of encouraging peace, developing respect for human rights and protecting the planet itself, the traditional disciplines of the Institute will need to reach out toward new forms of co-operation, including via the archival resources of Geneva, which constitute a long-forgotten cultural treasure that no other city of multilateralism can claim for itself. In so doing, the CDHM hopes to turn Geneva into a primary global destination for scholars in the humanities as well as for journalists, novelists and artists.

Electronic reference

Mallard, Grégoire, Davide Rodogno, and Lauren Riggs. “Why Art? Exploring the Role of ‘Art and Social Science’ Approaches to the Interdisciplinary Study of Multilateralism.” Global Challenges, Special Issue no. 3, October 2025. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/special_3/why-art-exploring-the-role-of-art-and-social-science-approaches-to-the-interdisciplinary-study-of-multilateralism. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-j8ne-em46.This bilingual special issue of Global Challenges has been jointly produced by the Geneva Graduate Institute’s Research Office and the Centre for International Studies (CERI – Sciences Po – CNRS). Coordination was provided by Miriam Périer for CERI and Marc Galvin for the Geneva Graduate Institute.

VIDEO: Alexandra Grimal (2020)

Domaine de Chambord

An inauspicious day from the get-go

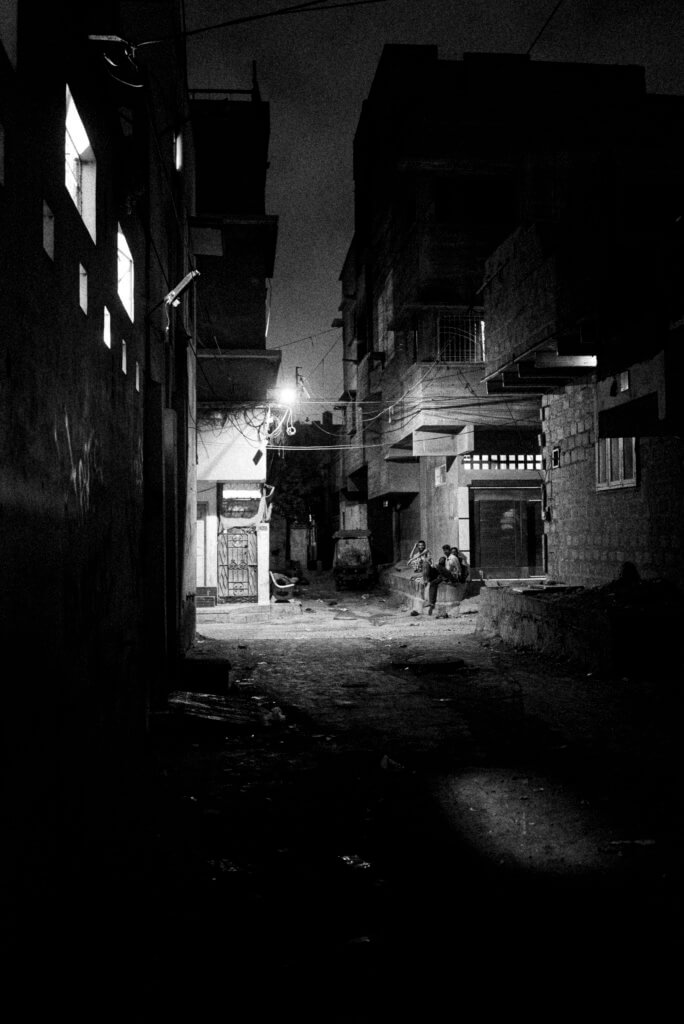

My poetry has always been influenced by other artistic media, including contemporary dance, music, and audiovisuals. ‘An inauspicious day from the get-go’ is a poem with direct roots in cinema. It is affected by the simple, striking, abrupt, and contradictory visual elements in the films of two avant-garde Palestinian directors: Hany Abu-Assad’s Rana’s Wedding and Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention and The Time that Remains. Similar to these films, the poem explores the indifferent, banal, and haphazard genocidal violence inflicted by, and inherent in, settler colonialism; so that regular, daily acts of the colonized, like talking on a phone, or looking out a window, become extremely dangerous actions.

Through the ‘colonial encounter,’ such simple acts transform into areas within which the colonized struggle to maintain their continuity, existence, and life, as contrasted with the colonizer’s core endeavor[s] of disruption, annihilation, death. This poem touches on these contrasts of ordinary, day-to-day living, examining how colonialism obliterates them to a point of no return.

An inauspicious day from the get-go

Some damn thing made her mom start talking to her about her fiancé yet again. “He’s just not cast from the same clay we are,” she said, “and I don’t think he’s really got it in him to make it a home.”

And as always happens at such times, the young woman shouted and swore, then she hurtled—like a metal water tank hoisted half-way up towards the roof slipping its trusses to crash back down—out of the house.

In the moment between her opening the front door and slamming it behind her, a tank passed; the sound of its tracks the crushing of little children’s bones, the smell of its exhaust charred corpses.

As she crossed over to the opposite sidewalk a sniper behind her shot a young man at the end of the street, of whom nothing had appeared in the machine gun’s sights except the hair on the back of his head.

Before she raised her hand to her friend’s doorbell a bulldozer had extended its metal claw towards the walls of the next-door building, so that it crumbled into pieces on the ground.

Under the rubble a doll with disheveled hair and dusty clothes was playing some music out of her belly, next to her a notebook in which the boy had drawn what he imagined of a bulldozer destroying a house that he imagined as his own.

The boy sits silent while the woman at his side (his mother) hits herself on the head, his father having preceded him to prison. The boy will grow up one day and will love a girl who has grown up also, and then he will be betrothed to her.

The boy who got engaged to the girl—after they grew up, and he got out of prison—had been saying goodbye to her at the end of the street, and stayed there watching her walk away until she entered her house. Then he slowly walked along the street from one end to the other, passing in front of the sniper, who eventually took the decision to put a bullet in the back of the boy’s head, after the tank had gone down the street, and he’d heard the sound of a door slamming and a girl had dashed by from one sidewalk to the other, all of which he took to be evil omens, and were.

Copyright © 2025 by Hisham Bustani. Originally published in A Poem-a-Day on January 27, 2025, by the Academy of American Poets.

Translated from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie.

VIDEO: Medical placement in the Solomon Islands

Bond University

Presentation of Destiny/Destination and reading of selected poems by Darius Kethari

Geneva Graduate Institute

VIDEO The Monkey in the abstract garden, Alexandra Grimal

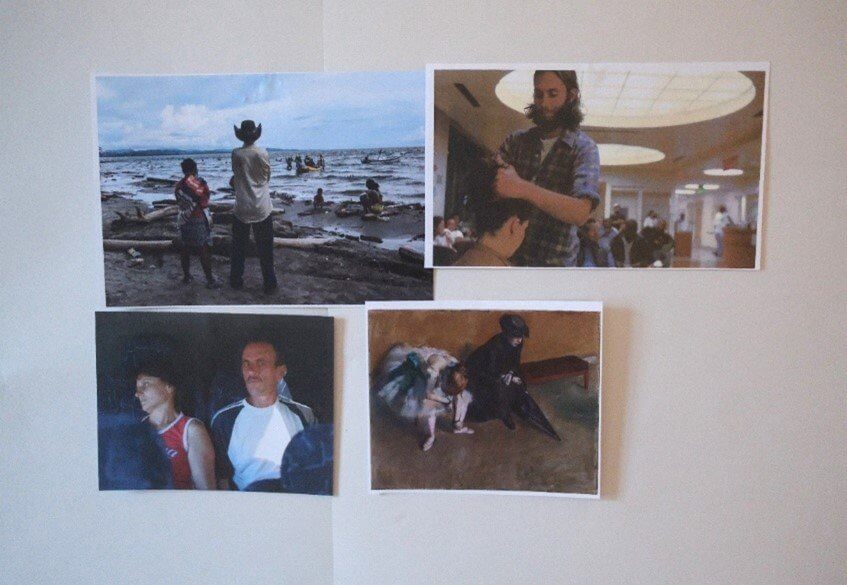

Montage 1: Waiting with, differentiated temporalities in shared waiting

It is unsurprising that waiting has a collective aspect, fostering interaction and potential solidarity. Yet, juxtaposing images like this film still from Peter Nicks’ The Waiting Room (a woman awaiting a consultation alongside her partner) and Edgar Degas’ painting L’Attente (a young dancer accompanied by a possible chaperone) raises questions about differentiated temporalities in shared waiting. How does the presence of accompanying individuals who share the waiting experience, even though they are not directly waiting for anything, alter the dynamic of waiting?

Nora Doukkali Elamajidi

Artistic collaborations with Carlo Vidoni (Destiny/Destination) and Loris Agosto (Homo Itinerans)

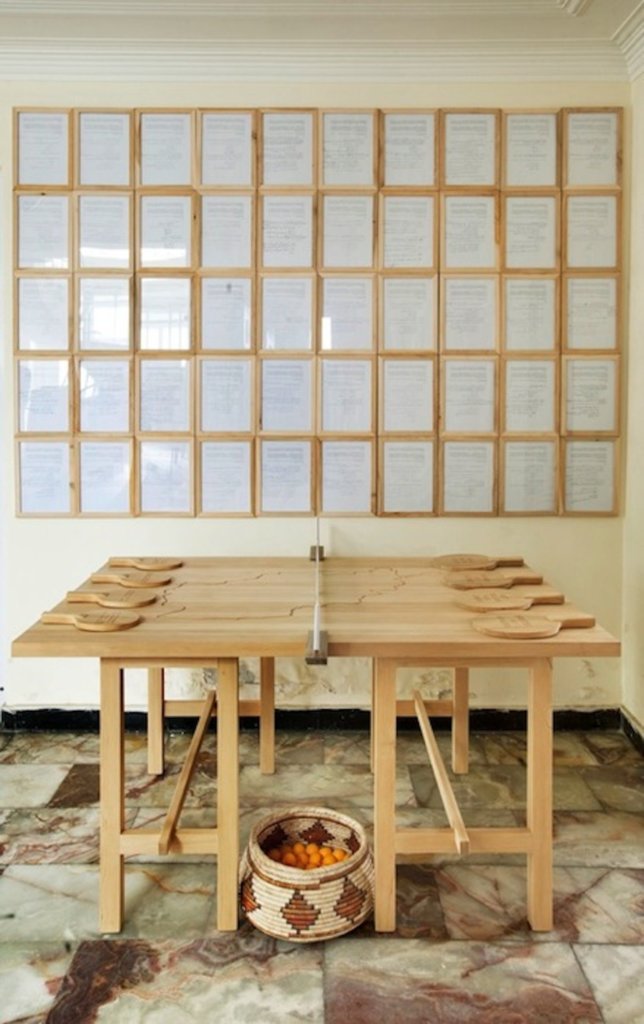

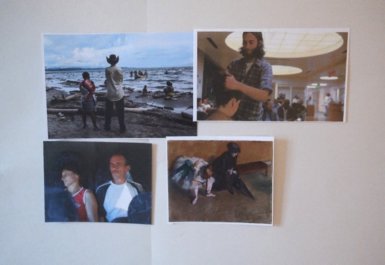

It was almost by chance that I began collaborating with two artists I knew from before. I first worked with Carlo Vidoni to design an exhibition entitled Destiny/Destination, which resulted in a polyphonic book bringing together interviews with migrants and poetic evocations, drawings and photographs (Monsutti & Vidoni 2023). The words we collected uncovered the vacuity of certain predefined categories: for example, the labels “economic migrants,” “asylum seekers” and “refugees” flatten a much more complex and diverse landscape. Our interlocutors spoke of their migration trajectory in terms of a tension between attachment to the places where they grew up and curiosity about the world that exists beyond the walls of their homes. These polymorphous conversations were translated into an open language that crossed the boundaries between social anthropology and visual art, between creators and the public, to reach people who could relate to the migration narratives and enrich them with their own experience. The lines on the palm of the hand were our visual and discursive starting point. They tell stories, they convey a message of singularity and, at the same time, of shared humanity, of idiosyncrasy and universality.

I Am From Where I Am Going, Geneva, March 2024 (A. Monsutti).

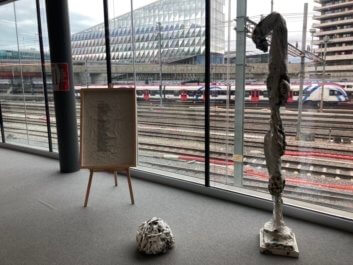

I Am From Where I Am Going, Geneva, March 2024 (A. Monsutti).Another artist, Loris Agosto, was struck by a sentence that an old man told me during my fieldwork in the mountains of central Afghanistan. I used this sentence to open the book Homo Itinerans (Monsutti 2020): “I come from where I am going!” An apparently paradoxical sentence, it is more than just a formula, it is an invitation to change our perspective and take a fresh look at human mobility. Here, social sciences inspired art through the production of sculptures in which human faces can be distinguished, without it being clear whether they are being born or being swallowed up by mud. The work was complemented by figurative texts I wrote to evoke migrants’ conditions of living and itinerancy as a way of being in the world (see more).

Alessandro Monsutti

The Garden of the (In)visible

The Garden of the (In)visible, Geneva, November 2024. © Alessandro Monsutti

The Garden of the (In)visible, Geneva, November 2024. © Alessandro MonsuttiIn line with Danto’s and Latour’s invitation to see art as a way of being and acting in the world, the installation The Garden of the (In)visible, co-created with my colleagues Roberta Altin, Giuseppe Grimaldi and Katja Hrobat Virloget, staged artefacts collected along the so-called Balkan Route, at the borders between Croatia, Slovenia and Italy. Here, objects are clearly social agents: they render visible people who were largely invisibilised. The installation was presented in public spaces and even on the streets, drawing attention to a socially sensitive situation, intentionally inviting polemic among people who might disagree in a way that participants in an academic conference would not. The process was participatory at each of its various stages: First, collecting the artefacts involved local authorities and activists, students and professors from the various universities of the region. Then, the installation was accompanied by events that brought together migrants who had taken the Balkan Route, people living near the various borders, and all those who joined the collect.

In this project, the differences between social sciences and art, but also between investigator and investigated, between curator and visitor, fade. It was not about communicating the work of social scientists to a broader audience but rather creating – beyond the narrow circle of university professors and students – a new epistemic and political community. We were modestly following Latour’s footsteps, making public debate more accessible and challenging taken-for-granted assumptions, but, more importantly, we hoped above all to open up new possibilities for action and coexistence.

Alessandro Monsutti

Hannah Entwisle Chapuisat’s current research explores how art…

My current research explores how art’s critical capacity to engage affect, the senses, and the imaginary might influence international norm evolution in intergovernmental venues, drawing on constructivist scholars Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink’s 1998 norm “life cycle” model that recognizes the role of “[a]ffect, empathy, and principled or moral beliefs” in international norm dynamics. I have found that when art is integrated within collective efforts to develop norms, it can increase global policymakers’ awareness and understanding, inspire ideational commitment, and generate creative thinking, which can all influence norm evolution processes. For example, in the context of a programme such as the UN80 Initiative – an initiative launched in March 2025 to make the United Nations more effective – art-based projects may stimulate more expansive and innovative reflection about the future of multilateralism. Rather than restricting the debate to what is financially and politically viable, art has the capacity to propose or test radical solutions that may embolden global policymakers to think bigger and perhaps arrive at more innovative visions.

Screening of Mati Diop’s 2024 film Dahomey at the CDHM (February 2025)

In February 2025, the CDHM hosted a screening of Mati Diop’s 2024 film Dahomey, a documentary following 26 objects from the former Kingdom of Dahomey as they leave Paris and are returned to present-day Benin. The screening was followed by a panel discussion on the “Diplomacy of Restitution: Issues of Knowledge and Powers”. Participants included leading academics, diplomats, curators and writers active in both Benin and Europe. Co-chaired by Doreen Mende, Director of Research of the State Art Collections in Dresden and Prof. Mallard, the discussion explored issues around how stolen art treasures can be received in a country which has reinvented itself in their absence. The panel covered themes ranging from the making of the film and panellists’ personal experiences of restituting archives to methods of postcolonial digitisation and digital archiving. Leading up to the event was a seminar for students at HEAD – Genève on collaborative projects on provenance research between African and Western researchers. A special session, “Within me resonates infinity”, based on the film, was held at the Museum of Ethnography Geneva (MEG) for students of HEAD – Genève and IHEID. Through the organization such multi-facetted events with a diversity of actors from different backgrounds, the CDHM hopes to break disciplinary and institutional boundaries, placing the Institute at the forefront of pedagogy on multilateralism.

Grégoire Mallard

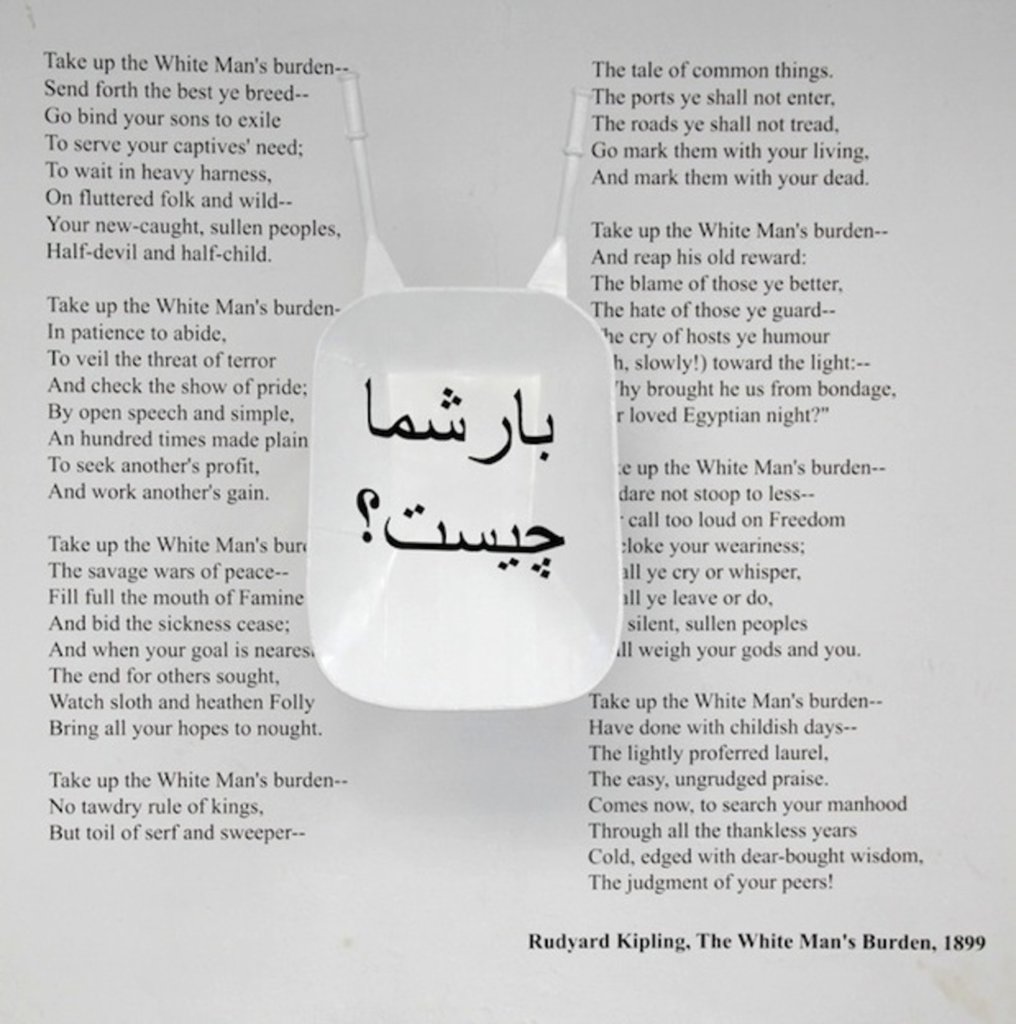

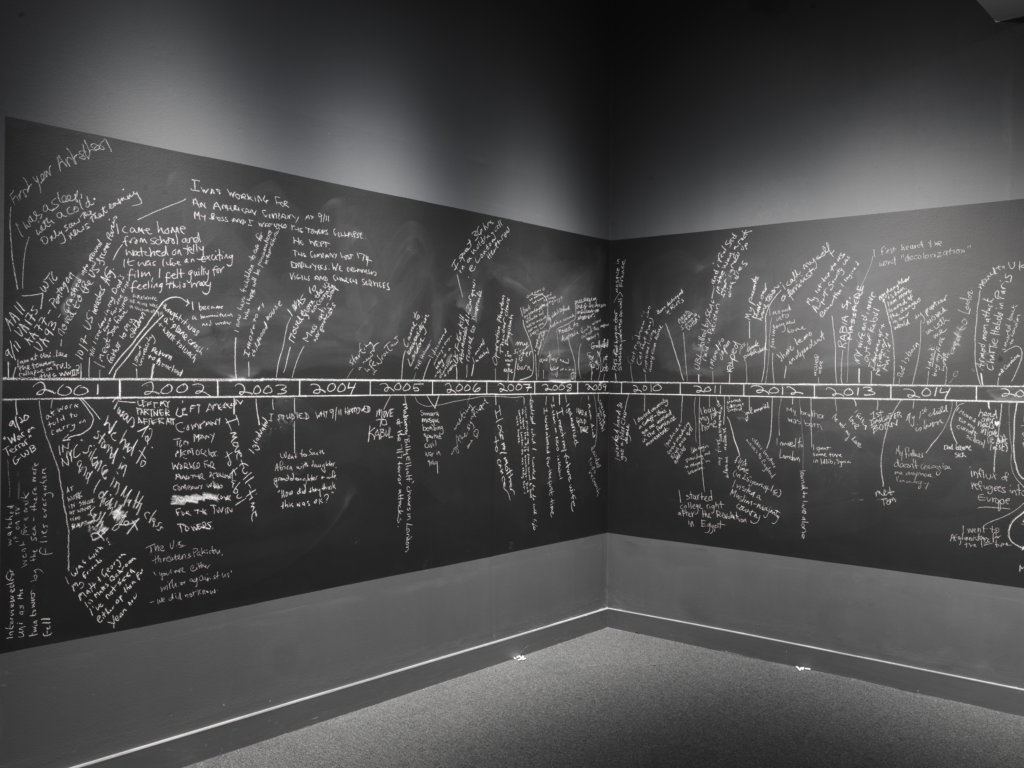

“Image wars”, a forthcoming project by Nataliya Tchermalykh

The first exhibition organized by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel in 2002, Iconoclash, examined the: the various attempts to destroy, prohibit or indeed protect religious as well as scientific and artistic images of God, nature and man. This theme of image wars will be further developed by Nataliya Tchermalykh, a CDHM affiliate researcher in a forthcoming project. The second exhibition produced by Latour and Weibel, Making Things Public, addressed what the organisers called the “atmospheres of democracy”, pairing an impressive range of philosophers, historians and sociologists, from Europe and the United States, with visual artists. Their task: to explore the variety of media via which citizens in modern democracies voice their political claims.

Gregoire Mallard

PODCAST: Makenzy Orcel. Le sensible, la raison et la compréhension du monde

Research Office – Geneva Graduate Institute

VIDEO Member State, UN and public engagement with artwork during negotiations

Youtube / VonWong

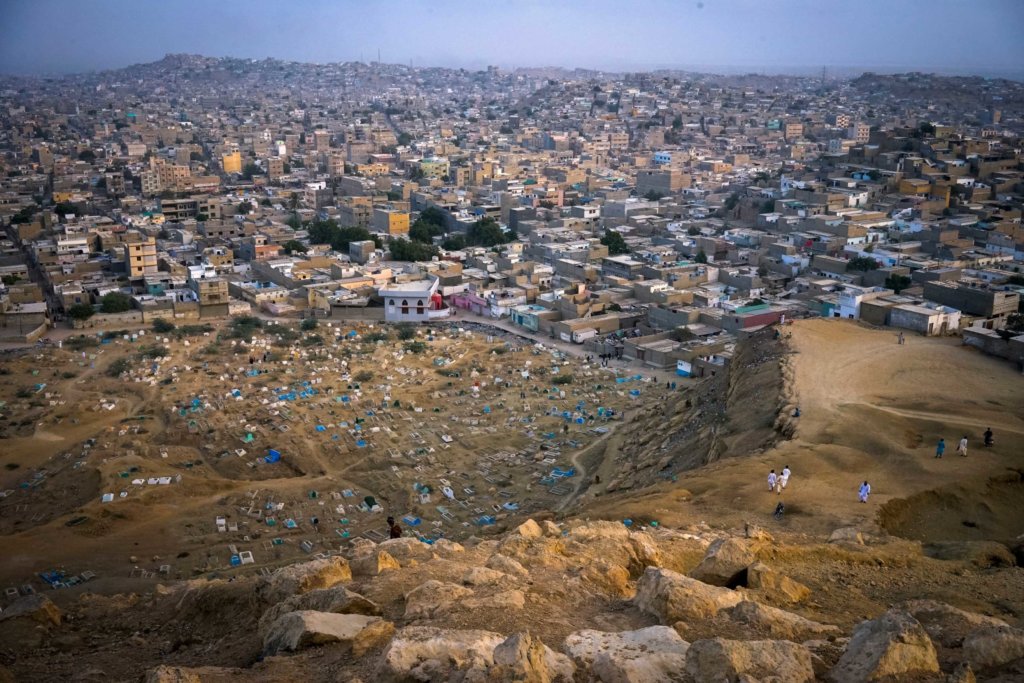

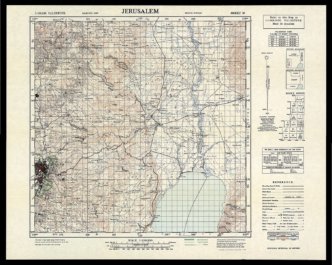

More on my ethnography of the Tubas Cluster Plan, by Dorota Kozaczuk

My ethnographic study of the Tubas Cluster Plan dates back to 2016, when the Palestinian consultancy CEP (Center for Engineering and Planning) began developing a regional master plan for the Tubas Governorate in the northern Jordan Valley. The project covered 118,297 square kilometres, including lands within the 1940 village boundaries of Tayasir and Bardala, as well as northern sections of Area C within Tubas city limits. Nine Palestinian communities were included in the planning framework: Al Malih, Ein al Hilwa, ‘Aqqaba, Tayasir, Khirbet Tell el Himma, Ibziq, Kardala, ‘Ein el Beida, and Bardala.

At the outset, the CEP team compiled available GIS maps, updated aerial photographs, and gathered archival data from Palestinian ministries and municipal authorities. They collaborated with a Belgian NGO and UN-Habitat as part of the project “Fostering Tenure Security and Resilience of Palestinian Communities through Spatial-Economic Planning Interventions in Area C (2017–2020).” Consultations were held with village mayors and governorate representatives, following participatory planning protocols developed by GIZ and the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government.

By 2019, during my participant observation in CEP’s Ramallah offices, four planning options had been prepared. I was shown the preferred version and invited to meetings where it was presented to stakeholders.

Aesthetic Vision and Political Friction

The Tubas Cluster Plan was visually compelling. On a printed A1 sheet, the region was divided into three zones: a deep green western section for agriculture, a faint brown central zone for mountainous terrain, and a dull green eastern area for pastoral land. Seven small zones, marked in vivid orange and bordered in blue, represented planned communities in the north, west, and east. CEP staff noted that the Israeli Civil Administration had approved plans for Tayasir, ‘Ein el Beida, and Bardala, while previously rejected plans for Al ‘Aqaba, Al Malih, Al Farisyia, and Karbala had been redesigned.

The plan proposed a road encircling the mountain range, connecting the seven communities, and included upgrades to existing roads in the west and south. Notably, it omitted Israeli settlements, the separation wall, and the military designation of much of the area. In this orthographic vision, the region functioned holistically for Palestinian life, with orchards and livestock populating the mountains and tourist routes inviting exploration. The Tubas Cluster Plan was both a misrecognition of occupation and an assertion of Palestinian reality—true to its survey methods, logically deterministic, and far from naïve.

Between Aspiration and Constraint

Shortly after my study, CEP submitted a report with four proposals to UN-Habitat, the Ministry of Local Government, and the Tubas Regional Committee. I attended the unveiling at the Palestinian Ministry of the Wall and Settlements. The meeting aimed to align institutional goals, but quickly revealed tensions. Ministers and engineers spoke of life near the Occupation Wall and recounted stories of displacement. One minister criticized the plan as disconnected from lived realities and questioned its aesthetics. A planner, however, defended the right to imagine beyond oppressive facts, arguing that the Tubas visualisation offered a glimpse of what that could look like.

The meeting ended without consensus. Ministerial support for a plan covering large swaths of Area C carried serious political implications: it risked undermining the Oslo Accords and provoking backlash from Israel and the international community. The plan’s aesthetic of misrecognition also conflicted with the prestige of “surveyed oppression,” which underpins legal and humanitarian support for Area C. In reality, Tubas remained a zone of daily survival under Israeli fire.

Weeks later, the CEP team presented the plan to the nine communities. At the Tubas Municipal Offices, the idea of a prosperous region was met with quiet resignation. It was deemed unachievable and received little attention.

By the end of the following month, CEP submitted individual village plans to the Israeli Civil Administration, aiming to expand them beyond Area B. These plans conformed to the aesthetics mandated by the ICA—complete with its loathed colour scheme and the infamous blue polygon.

By autumn 2019, CEP confirmed that the Tubas Cluster Plan had not been approved.

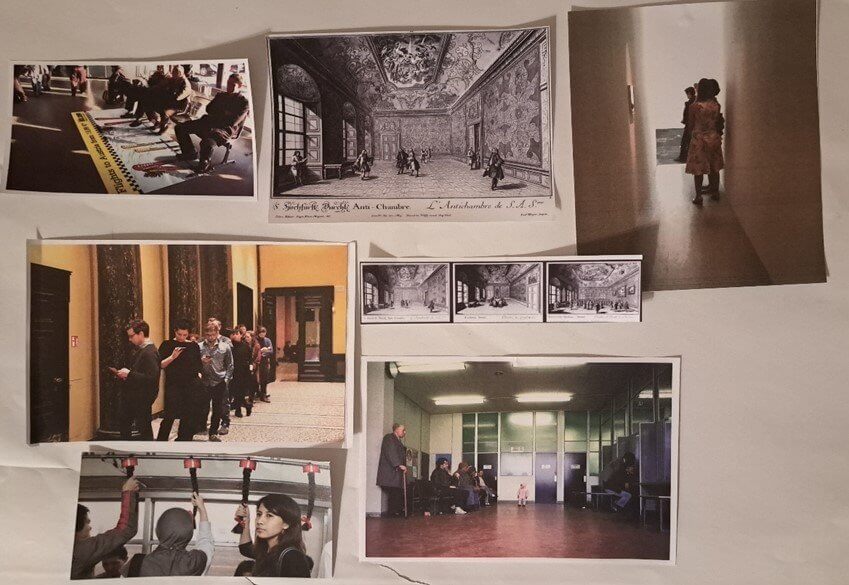

Montage 2: Spatialization of hope and frustration in public waiting spaces

When positioned in proximity to one another, images of public waiting spaces prompt reflection on how their architecture contributes to the experience of waiting. Several scholars have explored waiting as a tool of power. In this context, montages can help foster a closer engagement with how the materiality of spaces and objects configures waiting, embeds power relations and makes waiting individuals aware of their position relative to spaces whose thresholds they have crossed

Montage 3: Domestic waiting, gender and digital mediations

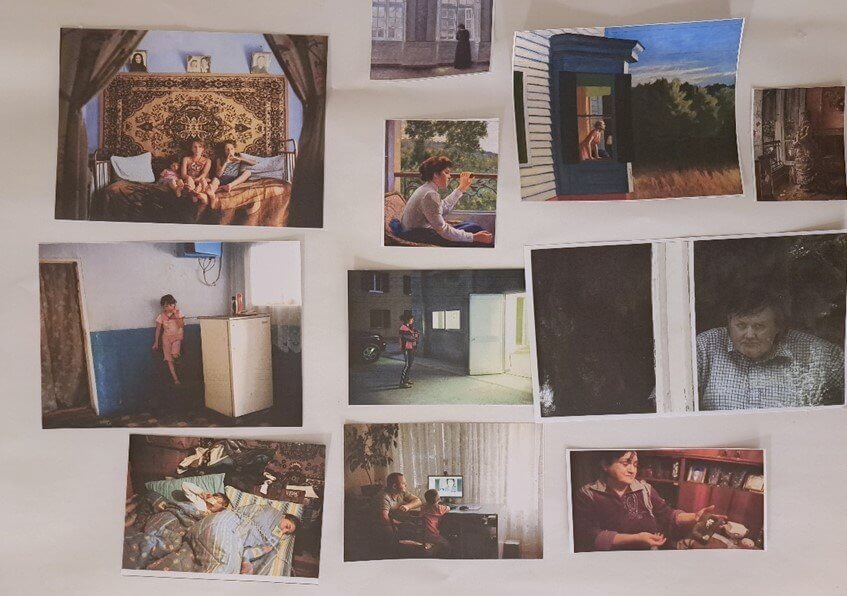

The third montage questions gendered narratives of waiting and domesticity. Some images depict women as passive figures, gazing through windows that symbolize thresholds between interiors as sites of non-events and external action. When these are arranged together with Andrea Diefenbach’s photos from the series Country Without Parents, showing Moldovan children waiting by phones or computers for news from their parents who work in Italy, they offer new avenues for reflection.

History of Palestinian Planning with maps and images

The Military Orders

Map No. 3243 Rev 4, Territories Occupied by Israel Since June 1967, United Nations, June 1997

Map No. 3243 Rev 4, Territories Occupied by Israel Since June 1967, United Nations, June 1997

On 1 June 1967, the Israeli military issued its first Military Order, declaring the Gaza Strip and the West Bank as closed military areas. Military Order No. 2 imposed martial law on the West Bank and transferred all legislative, executive, and administrative powers of the Jordanian government to successive Israeli military commanders. Under strict adherence to the Fourth Hague Convention, existing laws could not be altered.

Survey of Palestine 1944, 1:250,000 Sheet 2 (partial crop).

Survey of Palestine 1944, 1:250,000 Sheet 2 (partial crop).Survey of Palestine 1944, 1:250,000 Sheet 2 (partial crop).[/caption]As the occupying power, Israel inherited maps, plans, land laws, and regulations from the Ottoman, Jordanian, Egyptian, and British Mandate periods, spanning over 150 years. Israel immediately began enforcing a stringent military regulatory regime that referenced—but never overruled—existing legal frameworks. Within the first decade of occupation, two parallel strategies emerged: the adoption of most existing laws through Military Orders (MOs), and the centralization of administrative authority under the Area Commander. Palestinians were swiftly stripped of legal and civil rights previously guaranteed under British and Jordanian administrations.

Survey of Palestine 1942–1958, 1:100,000 maps, Survey Department of Palestine Israel enacted Military Order No. 418, titled Order Concerning the [Jordanian] Law for Town, Village, and Building Planning (1966).

Survey of Palestine 1942–1958, 1:100,000 maps, Survey Department of Palestine Israel enacted Military Order No. 418, titled Order Concerning the [Jordanian] Law for Town, Village, and Building Planning (1966).

Institutional Arrangements of the Israeli Physical Planning System in the West Bank, Abdel Rahman Abdel Hadi Mahrok (1995, p.126, Fig. 8.2)

Institutional Arrangements of the Israeli Physical Planning System in the West Bank, Abdel Rahman Abdel Hadi Mahrok (1995, p.126, Fig. 8.2)

Through MO 418, Israel effectively excluded Palestinians from planning processes. Over the following decade, Israel issued additional military orders—albeit more slowly—that restricted spatial planning practices to Israeli military personnel only.

Research Office

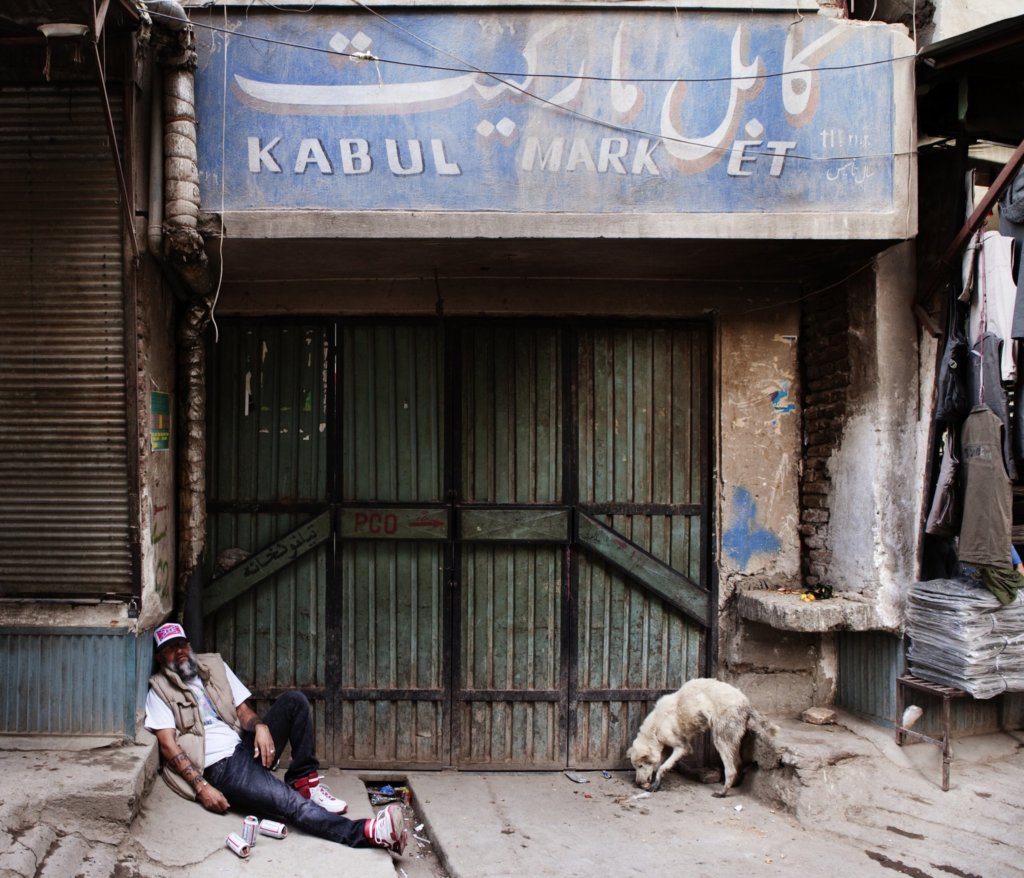

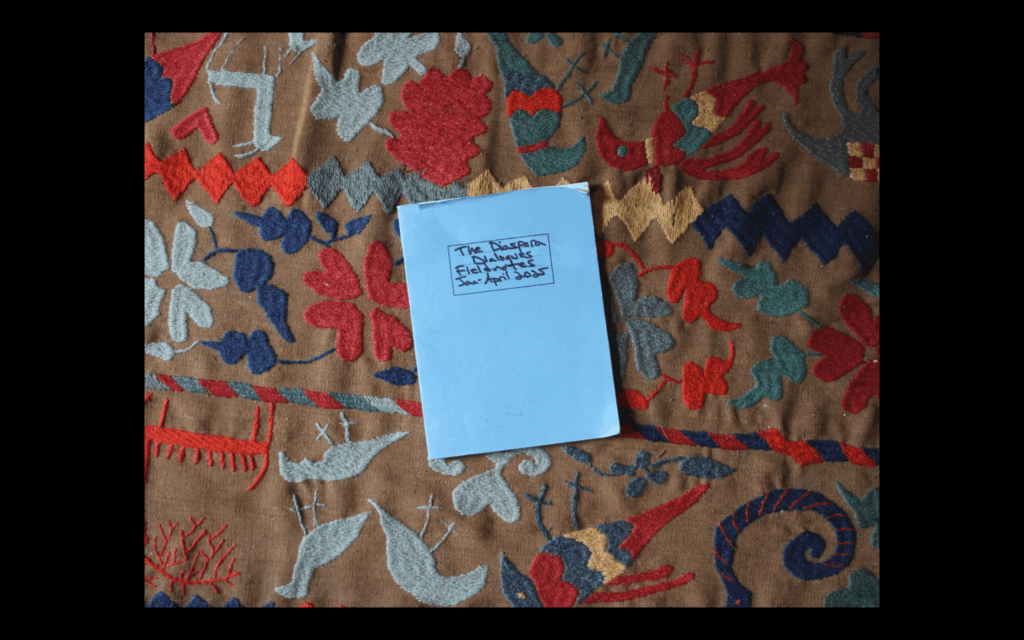

Me, Amanullah Mojadidi. Who I am…

I received a BA in the late 1990s and an MA in the early 2000s, both in cultural anthropology. I subsequently spent the next 20 years working both as a conceptual artist and a development worker in support of contemporary artistic initiatives in Afghanistan, before returning to academia to pursue a PhD, once again in cultural anthropology. My approach in using anthropology to make art has been to listen to local communities to understand what issues are important to them and then to work with them on defining not only what to represent, but how to represent it. This approach can be seen as falling within what George Marcus has termed “para-ethnographic”, a process in which the ethnographer (or the artist) is “allied with the subject as intellectual partner in coming to terms with the understanding of a shared common object of curiosity” (Holmes and Marcus 2020:29).

Research Office. Geneva Graduate Institute