Antagonisms in the South China Sea: The Regional Perspective

Southeast Asian nations’ protracted struggles for independence, combined with Cold War geopolitics, made maritime border delimitation a complex mix of cooperation and conflict. Great power politics remain the main drivers of tensions until this day.

By the 1990s, the scramble for ocean territories and their presumably “rich” resources came to resemble a gold rush with geopolitical undertones. Under these circumstances, none of the parties has been overly concerned with putting their claims in line with the principles of the international law of the sea. The Chinese, Taiwanese, Vietnamese and Philippine governments all use the concept of “historical waters” to assert exclusive rights to certain seas on the grounds that these have been known to, and used by, their precursors for economic, i.e. fishing and navigational references, as well as for defence purposes for centuries. These notions of “historical waters” clash with the concept of “international waters” that the United States uses to assert the “freedom of navigation”. Yet, neither of the terms makes part of the existing body of international law. What looks like mere legal quarrelling is the manifestation of the major contention, which underlies the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea: the fundamental conflict of interests between the developed and militarily strong great (naval) powers, which put utmost premium on the freedom of navigation, including for their warships, and lesser developed, weaker coastal states, which put premium on protecting their marine resources and keep the great powers’ navies at bay.

As they seemingly stabilise views of order, imagined geopolitical imperatives not only elevated the control over the South China Sea to a (de facto) “core interest” for the Chinese leadership, upholding “stability” through naval presence also became a touchstone for the credibility of US alliance commitments, and for the US role and self-conception as guarantor of the current world order more generally.upholding “stability” through naval presence also became a touchstone for the credibility of US alliance commitments, and for the US role and self-conception as guarantor of the current world order more generally. This revival of geopolitical ideas makes the resolution of maritime disputes across the dividing line between “East” and “West” – along Dean Acheson’s Cold War division of East Asia (Kimie Hara, Cold War Frontiers in the Asia Pacific, 2006) – more difficult and severely complicates efforts at tension reduction and cooperation.

Fragile Attempts at Cooperation in a Sea of Clashing National Interests

Disputes limited to either side of the geopolitical fault line are less complicated and have often been closer to resolution. Not only has the Chinese government managed to demarcate the land border with Vietnam, its most recent enemy at war; Beijing and Hanoi also successfully delimited their maritime boundary in the Gulf of Tonkin (Beibu). Despite frequent clashes in the nearby Paracel and Spratly groups, the pertaining fishery agreement works rather well, and from 2006 onwards the two sides successfully engaged in the joint exploration of the gulf. The adjudication of disputes among Southeast Asian states such as in the cases of the Pedra Branca islets between Malaysia and Singapore, and of Ligitan and Sipadan islands between Malaysia and Indonesia through the International Court of Justice, and the agreements on resource exploration between Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam are noteworthy too.

Yet, geopolitics, in conjunction with domestic power struggles, thwarted a major cooperative initiative that the Philippine, Chinese and Vietnamese national oil corporations undertook from 2003 onwards. Under the Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation had collected geological data in the Spratlys. These had been processed in Vietnam and were subsequently brought to the Philippines for interpretation – before politics trumped economics and brought the framework to a halt in 2008. Tensions with China escalated further after Vietnam and Malaysia jointly submitted their claims to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in May 2009, and when China seized Philippine-claimed Scarborough Shoal in April 2012 and blocked access to Second Thomas Shoal in May 2013. Yet, while Beijing’s reluctance to clarify the meaning of its sweeping nine-dash line and increasingly assertive stance on it put Chinese actions at the centre of attention and criticism, Vietnamese and Philippine approaches to the disputes were not static either.

Vietnam, a Communist Party–ruled country that had embarked on an opening and reform course similar to China’s, is economically very dependent on its northern neighbour. This situation induced and enabled the two governments to compartmentalise the territorial disputes in spite of popular opposition. Large-scale anti-China protests such as those triggered by Beijing’s placement of an oil rig into disputed waters in May 2014 can for the most part be attributed to general socio-economic grievances. Philippine politicians have been preoccupied with bigger problems than maritime territorial delimitation too. Hence, the state of relations with Beijing has fluctuated depending on incumbent presidents’ inclination and their grip on power. While Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (2001–2010) had been pragmatic in dealing with Beijing, her successor, Benigno Aquino III, generally leaning toward Washington, oversaw a cooling down of ties with China. By contrast, Rodrigo Duterte, elected to president in June 2106, has shown a pragmatic stance that elicited a positive reaction from Beijing and enabled rapprochement. Despite their overlapping claims, Malaysia and China maintain a “special relationship” in which both sides deliberately refrain from irritating one another. This can be explained by the relatively smaller overlap of their claims, Malaysia’s relatively greater concerns about Indonesia, and Kuala Lumpur’s traditionally Asianist foreign policy orientation. Extending from the Natuna Islands, Indonesia’s claim slightly overlaps with the Chinese U-shaped line too. Yet, only in March 2016 Jakarta got drawn into the quagmire when Chinese and Indonesian fishermen clashed in what both parties see as their “traditional” fishing grounds.

A Ruling Further Exacerbating Tension

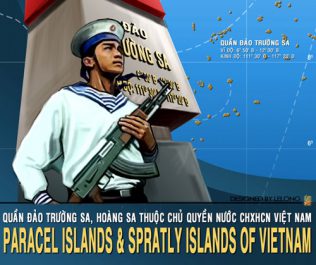

Propaganda poster for Vietnam’s maritime claim over the Paracel and Spratly Islands.

Propaganda poster for Vietnam’s maritime claim over the Paracel and Spratly Islands.The diversity of views within Southeast Asia also became visible in the official reactions to the Arbitral Tribunal's decision on the Philippine-initiated case against China. While Manila welcomed the tribunal’s support, it nevertheless called on all parties to exercise “restraint and sobriety”. Vietnam did not voice any opinion. Malaysia and Indonesia called for “restraint” and the latter, similarly to Singapore, insisted on the use of legal and diplomatic means. Taiwan, due to its identical claim with China a de facto loser too, decried the ruling as unacceptable and non-binding because it had neither been invited to take part in the case nor been consulted. In contrast, Beijing reacted strongly and rejected the proceeding of the arbitration, despite its legally grounded refusal to participate, as yet another “humiliation” by “Western” neo-imperialist powers. The fact that the US and Japanese governments insisted that China follow the ruling and used the arbitration to pressure Beijing revealed and further reinforced the perception of an “East”, represented by China, clashing with the “West”, represented by the United States and its allies. Spurred by this geopolitical rivalry, tensions in the South China Sea have over the last five years clearly increased and threatened to divide East Asia anew. To begin with, hard security interests have trumped fragile diplomatic attempts at calming the situation, for example, through the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea on which the Association of Southeast Asian Nation (ASEAN) and China had agreed in November 2002.

ASEAN’s Missed Opportunities

What is more, the historical failure of the ASEAN foreign ministers to issue a joint communiqué at the end of their 2012 meeting in Phnom Penh revealed how geopolitics undermines regional community-building efforts and threatens ASEAN’s very purpose.What is more, the historical failure of the ASEAN foreign ministers to issue a joint communiqué at the end of their 2012 meeting in Phnom Penh revealed how geopolitics undermines regional community-building efforts and threatens ASEAN’s very purpose. Aided by China’s sheer economic weight and its enhanced disbursement of official development assistance, including through the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing’s envoys so far managed to keep Southeast Asian nations from uniting against China’s gradually solidifying U-shaped maritime claim. Economic concerns have long been dividing ASEAN into the two sub-groups of the five founding members (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) and its newer Indochinese or continental members, the so-called CLMV (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam), who tend to be more dependent on China.

Yet, the reason for rising tensions must be found, above all, in the perceived geopolitical imperatives which push decision-makers in Beijing to compete with their peers in Washington over the control of what they all perceive as “strategically” important waters. Rather than prioritising stable ties, which would provide joint access to hydrocarbon resources and enable the establishment of frameworks for sustainable fishery management, governments engage in mutual finger-pointing while at the same time claiming to further “stability” and “peace”. This sharpening rhetoric could well indicate the acceleration of a trend toward the opposite.

In summary, the conflicts over a few reefs and rocks far out in the South China Sea, combined with the imaginary of so-called sea lanes of communication – that is, global shipping routes, to be nationally controlled and secured – have come to determine much of East Asia’s future. A weakening of ASEAN would mean the end of cooperative regional projects and lead to the problematic isolation of China, a China facing a “Western” military alliance and in need of allies of its own. Meanwhile, the real problems such as environmental degradation and income inequality, which populations throughout the region are facing day by day, remain unaddressed.

Political regimes in the region

| Countries | Political regime |

|---|---|

| China | Socialist republic |

| Indonesia | Republic |

| Malaysia | Constitutional monarchy |

| Philippines | Republic |

| Taiwan | Socialist republic |

| Thailand | Constitutional monarchy |

| Vietnam | Communist state |

Source: Asia Economic Institute.

Fisheries data: TOTAL CATCHES IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA, 2005–2010

Source: Allison Witter et al., “Taking Stock and Projecting the Future of South China Sea Fisheries”, Working Paper 2015-99, Fisheries Centre, University of BritishColumbia, Vancouver, 2015.

Estimated Proved and Probable Oil and Gas Reserves in the South China Sea

| Countries | Crude oil and liquid reserves (billion barrels) | Natural gas reserves (trillion cubic feet) |

|---|---|---|

| Brunei | 1.5 | 15 |

| China | 1.3 | 15 |

| Indonesia | 0.3 | 80 |

| Malaysia | 5 | 4 |

| Philippines | 0.2 | - |

| Taiwan | - | - |

| Thailand | - | 1 |

| Vietnam | 3 | 20 |

Source: US Energy Information Administration, 2013.

South China Sea: Elementary Data

East Asia

3.5 million km²

Brunei, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam.

Petroleum, natural gas and fisheries products.

Each year, USD 5.3 trillion of trade passes through the South China Sea; US trade accounts for USD 1.2 trillion of this total.

The South China Sea contains over 250 small islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs and sandbars, most of which have no indigenous people, many of which are naturally under water at high tide, and some of which are permanently submerged.

Source: by Galvin and whybe.ch.

The Disputed Islands

The Spratly Islands are a disputed group of 14 islands, islets and cays and more than 100 reefs, sometimes grouped in submerged old atolls. The archipelago lies off the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia and southern Vietnam. The islands have no indigenous inhabitants, but offer rich fishing grounds and may contain significant oil and natural gas reserves. Some of the islands have civilian settlements, but of the approximately 45 islands, cays, reefs and shoals that are occupied, all contain structures that are occupied by military forces from Malaysia, Taiwan, China, the Philippines and Vietnam. Additionally, Brunei has claimed an exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

The Paracel Islands are a group of islands, reefs, banks and other maritime features. They are controlled (and occupied) by China, and also claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam. The archipelago is surrounded by productive fishing grounds and a seabed with potential, but as yet unexplored, oil and gas reserves.

Scarborough Shoal is a disputed territory claimed by China, Taiwan and the Philippines. Since the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff, access to the shoal has been restricted by China. Scarborough Shoal forms a triangle-shaped chain of reefs and rocks with a perimeter of 46 km. It covers an area, including an inner lagoon, of 150 km2. The shoal’s highest point, South Rock, measures 1.8 m above water during high tide.

The Pratas Islands are an atoll in the north of the South China Sea consisting of three islets about 340 km southeast of Hong Kong. Excluding their associated EEZ and territorial waters, the islets comprise about 240 ha, including 64 ha of lagoon area. China claims the islands, but Taiwan controls them and has declared them a national park. The main island of the group, Pratas Island, is the largest of the South China Sea islands.

Macclesfield Bank is an elongated sunken atoll of underwater reefs and shoals. It lies east of the Paracel Islands, southwest of the Pratas Islands and north of the Spratly Islands. Its length exceeds 130 km southwest-northeast, with a maximal width of more than 70 km. With an ocean area of 6,448 km2 within the outer rim of the reef, although completely submerged without any emergent cays or islets, it is one of the largest atolls of the world. Macclesfield Bank is claimed, in whole or in part, by China and Taiwan.