Historical Foundations of Human Rights and Contemporary Crises

BOX: Human Rights across and beyond Cold War Divisions

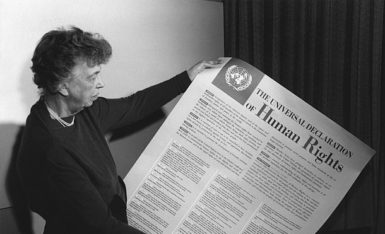

Eleanor Roosevelt holding poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in English), Lake Success, New York. November 1949.

Eleanor Roosevelt holding poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in English), Lake Success, New York. November 1949.In the post-1945 period, different understandings of human rights arose, were advocated, and often blatantly violated, across and beyond Cold War divisions in complex and unexpected ways. A standard version of human rights history portrays Western countries as strong supporters of civil and political rights and the Soviet bloc as staunchly defending social, economic and cultural rights. This dichotomy is correct only if we conceive of it as a matter of emphasis, rather than essence. True, in the late 1940s, many Western governments were sceptical of the justiciability of social and economic rights. By contrast, the Soviet Union branded social rights as an ideological weapon to denounce the inequalities inherent in capitalist societies. Yet, one should not forget that the years between 1945 and 1975 were the “golden age” of the welfare state. Hence, although, broadly speaking, in the West social and economic rights were seen as more aspirational than civil and political rights, there was strong consensus that they had to be included in key documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the two later human rights covenants (although doubts about justiciability resurfaced in the negotiations for the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, which eventually excluded them). A matter that divided much more strongly East and West in the late 1940s was the inclusion of collective rights, notably minority rights, in the UDHR. Most Western delegations defended an individualist (and assimilationist) understanding of human rights, arguing that non-discrimination clauses would be sufficient to protect minorities. Communist countries, by contrast, strongly advocated the inclusion of an article on the cultural and linguistic rights of minorities.

These disagreements notwithstanding, in the late 1940s, the US and the USSR did agree that any serious step towards implementation had to be put off for the foreseeable future. In the following two decades, they defended their respective emphasis on individual or collective rights, wielding their own understanding as an ideological weapon to denounce violations in the opposite bloc, but doing little to advance enforcement. Within this confrontation, in the 1960s, postcolonial countries emerged as a key human rights player. Shifting the focus over matters of racial discrimination and self-determination, they reenergised the human rights agenda at the UN, as witnessed by the adoption of the first legally binding human rights treaties: the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), in 1965, and the two International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), in 1966 – the 1948 Genocide Convention was not generally considered as a human rights treaty in the late 1940s as it is today. Postcolonial human rights advocacy at the UN in the 1960s challenges claims that human rights are simply a Western invention imposed on the Global South. Yet, by the early 1970s, the “honey moon” between human rights and postcolonial states was over. The spread of authoritarian regimes committing serious human rights violations and a heavier concern with North-South economic redistribution reduced Global South’s interest in advancing human rights at the UN. Hopes that the Global South could lead a human rights revolution were dashed.

It is within this general mood of disillusion that the “human rights breakthrough” of the second half of the 1970s occurred. The international human rights movement that arose then portrayed itself as apolitical, as appealing to a “higher morality” escaping the polarised logic of the Cold War. Not surprisingly, one of Amnesty International most successful campaigns consisted in choosing three political prisoners, one each from the First, Second, and Third World (in then language). As Andrei Sakharov made clear, “what we need is the systematic defence of human rights and ideals and not a political struggle” (Sakharov Speaks, Alfred A. Knopf, 1974, p. 44). Contemporary understandings of human rights have much to do with a commitment to protecting human lives from harm as with scepticism about grand ideological projects of political and social transformation. Whether human rights can legitimately claim to be a minimal ideology based purely on morality is however debatable, as recent criticism of its supposed universality suggests.

Emmanuel Dalle Mulle

Research Associate at the Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Postdoctoral Researcher, Complutense University of Madrid