Between Security and Apartheid: Cinematic Representations of the West Bank Wall

Cinematography offers an important complement to the social sciences’ research on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict narrative as it allows to uncover new strata of popular memory and social history. Documentaries, in their different forms, provide the sensuous experience of sounds and images organised in a way that stands for something more than mere passing impressions. They express emotions and concepts in their intricate nature but in a codified and at times abstract way. Moving images – as illustrated by the three examples below – tell the daily consequences of the Israeli wall, and how these are represented and interpreted by one Israeli and two Palestinian filmmakers.

Three documentaries, all focused on the wall in the West Bank, look particularly compelling today in light of the new Israeli Organic Law adopted by the Knesset in July 2018. Conceiving the right to self-determination exclusively for its Jewish citizens, it paves the way to an official form of “ethnocracy” and risks turning Israel into an apartheid state. Encouraging the colonisation of the Occupied Palestinian Territories, the law explicitly considers the Jewish settlements as an endeavour of national value.

Wall (2004, 96 min.), by Simone Bitton, is a documentary showing the rationale and mechanisms behind imprisoning and enclosing two people on both sides of the wall. That this almost 700-kilometre-long proposed stretch of asphalt, wire, trenches and concrete recalls the Berlin Wall is just one of its many wrenching paradoxes. The wall is part of a larger matrix of control over the Palestinian population and their territory, combining different kinds of checkpoints, watchtowers and separate roads for the Jewish settlers and the Palestinian laymen. Officially justified by the Israeli need of security, the wall is a real dispositif in Foucauldian terms, aimed at breaking the people’s will to resist occupation and destroying their livelihoods. The documentary is also a powerful cinematic meditation on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by a French-Israeli film director of Jewish Moroccan origin.

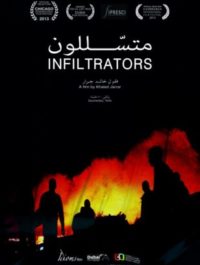

Palestinian film director, performer and photographer – but also officer in the Presidential Guard of the Palestinian Authority – Khaled Jarrar shot Infiltrators (2012, 70 min.) as a “road movie” with a handheld video camera over four years. It chronicles the daily attempts of Palestinians seeking routes through, under, around, and over a matrix of barriers erected by Israel, including the 7-metre-high concrete wall. According to the film director, between 200 and 400 workers try to sneak out of the wall each weeknight, and almost 1,000 per night on weekends. Some attempts end in failure, and others in success. It’s a cat-and- mouse game, in which failure seems to lead to more persistence.

Jordanian-Palestinian filmmaker Mohammad Alatar’s Broken (2018, 94 min.) tells the juridical debate on the wall, across three continents and through the testimonies of judges and international lawyers. Upon request of the UN General Assembly about the legality of the wall – mainly built on the Palestinian side of the 1949 “Green Line” – the International Court of Justice declared in 2004 the wall contrary to international law, and called upon Israel to desist from constructing it and to make reparations for damages caused. To date, no action has been taken by Israeli authorities.

The three movies, each in its own way, cast doubt on the official reasons advanced by Israel for building an “antiterrorist” barrier. Wall clearly exposes the policy of land grabbing separating farmers from their land and Palestinians from their places of work, healthcare and educational facilities; Infiltrators demonstrates the wall’s permeability and reveals the business between Palestinian smugglers and Israeli collaborators who bring the “illegal” workers to selected sites. Finally, Broken reassesses the illegality of the wall according to international law.

In his Introduction to Documentary (Indiana University Press, 2001), Bill Nichols reminds us that documentaries shape collective memories and historical narratives by producing photographic records and visual perspectives of more or less distant events. As such, they become one among many voices in an arena of social debate and contestation. The fact that documentaries are not a straightforward reproduction of reality but the expression of particular points of view and visions of the world makes them potent speech acts in the social and political arena.

The three movies retrospectively document the (untold) annexation plan of the West Bank pursued by Israeli authorities over the past decade. A plan that, with Trump’s America support, is materialising in spite of the dangers Israel is facing: will its label of a “democratic state” still be meaningful? The Israeli settler colonial project may finally become reality, but it will not be without a price, that of killing the dream of a peaceful coexistence with the Palestinians. More than that, it risks polarising the Jewish communities both in Israel and abroad…

Fact Sheet: The Israeli West Bank Barrier

Cost: each kilometre costs EUR 2 million, for a total cost of approximately EUR 1.4 billion.

Size: 700 km.

Origin: the barrier was built in 2002, during the Second Intifada that had begun in September 2000, and was officially justified by the Israeli need of security against the wave of violence.

Prof. Cyrus Schayegh on the Wall, Israel and History

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

Increasing Number of Walls in the World, 1945–2018

Based on Samuel Granados, Zoeann Murphy, Kevin Schaul and Anthony Faiola, “Raising Barriers: A New Age of Walls”, The Washington Post, 12 October 2016.

United States/Mexico

India/Bangladesh

Kenya/Somalia

South Korea/North Korea

Turkey/Syria

Israeli West Bank Barrier

1,120 km between California and Texas, around a third of the total border length of 3,141 km.

Origins

- In 1994, US Border Patrol installed sensors and stronger fencing in San Diego, California, and El Paso, Texas. In the fall of 2006, the Congress authorised the construction of 700 miles of fencing in rural areas in California and Arizona. In January 2017, President Trump signed an Executive Order to begin the extension of the border wall.

The fence covers 3,200 km of the 4,096.7-km-long border

Origins

- The fence finds its origin in the Assam Accord of 1985 signed between representatives of the Government of India and the leaders of the sub-national Assam Movement. The accord accommodated the claims of the Assam Movement to keep out irregular migrants. The construction of the fence started in 1993.

8 km already done of the 700-km-long project

Origins

- Following the siege of Garissa University in 2015, the Kenyan government announced the construction of the wall.

- Project stopped in January 2018 to open negotiations with the Somalian Government.

764-km-long wall

Origins

- In March 2015, Turkey closed its border with Syria.

- In August 2015, the first section of the border wall was constructed in Reyhanli.

- The wall was completed in June 2018.

The DMZ is 250 km (160 miles) long and about 4 km (2.5 miles) wide.

Origins

- In the Armistice Agreement of 27 July 1953, the DMZ was created as each side agreed to move their troops 2,000 m (2,200 yards) back from the front line, creating a 4-km-wide (2.5-mi-wide) buffer zone.

700 km.

Origins

- The barrier was built in 2002, during the Second Intifada that had begun in September 2000, and was officially justified by the Israeli need of security against the wave of violence.

Definition of “Wall”

“The English word ‘wall’ is derived from the Latin vallus meaning a ‘stake’ or ‘post’ and designated the wood-stake and earth palisade which formed the outer edge of a fortification. Walls have traditionally been built for defense, privacy, and to protect the people of a certain region from the influence or perceived danger posed by outsiders” (from Joshua J. Mark, Ancient History Encyclopedia, https://www.ancient.eu/wall/).

Walls are social constructions that are often used in a metaphorical sense, serving as canvas to cultural and/or political projections. An example in point is the 1979 album The Wall of the progressive/psychedelic rock band Pink Floyd. Physical walls are the offspring of our mental walls but physical walls, in turn, also impact our mental maps and the way we configure spatial identities and alterity.

In academic terms, walls have further been described as “an exercise in verticality” (Carl Nightingale), as “top-down controlled sluices of human movement, points of banishment, and perfect locations for tax collection” (Carl Nightingale), as “material things with symbolic meaning” (Tamar Herzog) and, finally, as “sites of negotiation and practice-making or -following” (Tamar Herzog).

All quotes from Suzanne Conklin Akbari, Tamar Herzog, Daniel Jütte, Carl Nightingale, William Rankin and Keren Weitzberg, “AHR Conversation: Walls, Borders, and Boundaries in World History”, American Historical Review 122, no. 5 (2017): 1501–1553, doi:10.1093/ahr/122.5.1501.