Humanitarians as Targets of Violence?

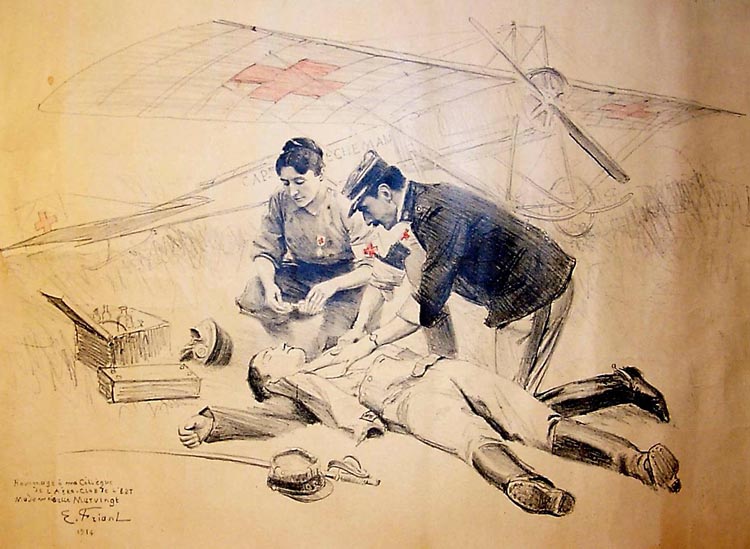

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-bfjt-3343The quote “In internationalized conflicts, such as in Afghanistan and Syria, Western aid workers have become targets, kidnapped by militants angling for a hefty ransom or killed in an attempt to send a message to the West.”reproduced on the right reflects a prevailing narrative that portrays humanitarian workers as increasingly targeted by deliberate attacks. It comes from an article released on 30 October 2018 by Voice of America under the title Humanitarian Groups Seek Ways to Reduce Attacks on Aid Workers. Historical evidence, however, tells us that there has never been a golden age in which humanitarians were immune from such attacks.

The Aid Worker Security Database (AWSD), which records major incidents of violence against aid workers since 1997, reports that the total number of security incidents dramatically increased since the turn of the millennium: from 29 in 2001 to 265 in 2013, affecting 475 aid workers that year. Since then, the number of security incidents has gone down to 158 in 2017, hitting 313 aid workers. Of those, 90% were national staff and 10% international staff, which does not support the argument that attacks would target first and foremost Western aid workers. Out of the 313 people hit in 2017, 139 were killed, 102 wounded and 72 kidnapped.

Over the same period, the humanitarian market has boomed and the number of aid workers operating in war-torn countries has soared as well. Yet, without accurate data on the number of humanitarians operating in the field, the question of the relative increase in security incidents remains open: we do not know the extent to which the probability of an individual aid worker suffering a security incident has increased at the global level. Besides, the situation varies greatly depending on the organisation and the context. Over the past ten years, the majority of security incidents took place in a few countries with a record 422 incidents in Afghanistan, followed by 211 in South Sudan, 173 in Somalia and 159 in Syria.

The reasons of security incidents

What are some of the reasons behind the surge in the absolute number of security incidents since 2001? The multiplication of humanitarian organisations on the ground – and hence greater risk exposure – together with enhanced media coverage of security incidents and better reporting are part of the explanation. But the evolving nature of warfare is also key. The Aid Worker Security Report 2017 argues that while states were responsible for the highest number of aid worker fatalities, most incidents were attributed to the proliferation of decentralised non-state armed groups (NSAGs), including targeted attacks by globalised NSAGs such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State. The increasing fragmentation of such groups, coupled with rapidly shifting alliances, makes it harder for humanitarian organisations to obtain and maintain solid security guarantees. A 2018 study by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reports that nearly half of armed conflicts involve between 3 and 9 opposing forces while 22% of them have more than 10. In the Libyan city of Misrata, over 230 armed groups were registered by October 2011.

The rise in security incidents is also linked to the blurring of lines between politically and economically motivated violence Urban warfare intensified in recent years. The use of heavy weapons and explosives in densely populated areas (e.g. Mosul, Aleppo) – combined with targeted attacks on healthcare facilities – has increased the risk of civilians and aid workers being injured or killed. This is the result of disregard for the protection of civilians and the medical mission, which can be compounded by greater difficulty in abiding by the principles of precaution and proportionality when hostilities rage in urban environments.

The rise in security incidents is also linked to the blurring of lines between politically and economically motivated violence. The number of recorded kidnappings rose from 7 in 2003 to 66 in 2013, often with demands ranging from monetary ransoms to political concessions such as the release of prisoners, or a commitment to refrain from attacking specific locations over a given timespan.

What can be done about it?

What can be done about it? Staff security must of course be a top priority all the way from field offices to headquarters, at all levels. The protection of healthcare workers and facilities is being promoted through advocacy campaigns and diplomatic efforts. The capacity of humanitarian workers to conduct frontline negotiations is being strengthened. Each serious security incident has to be carefully analysed in order to identify the specific underlying causes and the lessons to be drawn and shared. There is also a concern to build and nurture a solid security culture within humanitarian organisations as a key element of a broader security policy. Every aid worker operating in the field has a stake in security management. An inappropriate act or misbehaviour can affect the security of other colleagues within an organisation.

For an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian organisation like the ICRC, it is critical to be accepted by all actors with influence on staff security, and to ensure adequate security guarantees from the parties to the conflict. Maintaining close physical proximity to the affected population – which can increasingly be complemented with “digital proximity” – is essential to securing broad acceptance, not only of the type of humanitarian action undertaken, but also of its actors and purposes. Often, this entails making sure that humanitarian action is understood to be aimed at saving lives, alleviating suffering and protecting human dignity – not at transforming societies and polities or winning the hearts and minds of specific groups for a political agenda.

Maintaining close physical proximity to the affected population is essential to securing broad acceptance of the type of humanitarian action undertaken, but also of its actors and purposes. The presence of criminal groups in war is nothing new, and conflict financing is as old as war itself. Yet the blurring of lines between political and economic agendas in war raises the question of how feasible it is to get security guarantees from armed groups primarily driven by the pursuit of profits from the war economy, or of how far it is necessary to avoid encounters with them altogether (e.g. moving by air rather than by road to limit kidnapping and extortion risks).

In specific circumstances, resorting to exceptional measures such as armed escorts or armoured vehicles may be required. This can offer temporary options for delivering assistance and seeking to protect people in war, but should never be the default nor long-term solution. “Bunkerising” humanitarian action reduces proximity, may feed distrust and reduce acceptance: a vicious circle to be avoided whenever and wherever possible. Digital proximity with people affected by armed conflict offers an additional option to keep interacting and maintain two-way communication even as insecurity temporarily prevents presence in the field.

Electronic reference

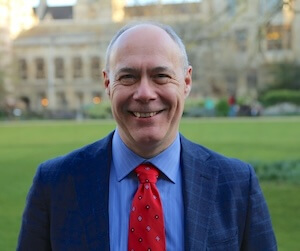

Carbonnier, Gilles. “Humanitarians as Targets of Violence?” Global Challenges, no. 5, April 2019. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/5/humanitarians-as-targets-of-violence. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-bfjt-3343.Map based on the data produced by the Small Arm Survey, and enriched by the Graduate Institute’s Research Office in Geneva, in collaboration with whybe.ch.

Migration, Violence and War, with Charles Heller

Graduate Institute – Research Office

State-Based Conflict since 1946

© ourworldindata.org / CC – Creative Commons

Source: Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)

Variable description: Ongoing conflicts are represented in each year in which more than 25 deaths occurred.

Violence, Killer Robots and Regulation, with Paola Gaeta

Graduate Institute – Research Office

Terminology Related to Violence and Conflict

The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.

The World Health Organization (WHO)

Derived from the Latin word conflictus, which means collision or clash. This term is understood as a disagreement between two or more parties through which the parties involved perceive a threat to their needs, interests or concerns. Source

A dispute involving the use of armed force between two or more parties, often referred to as war. Source

Militarised armed conflict between two or more states. Source

A conflict between a government and one or several non-governmental parties, often with interference or support from foreign actors.

The intentional use of illegitimate force (actual or threatened) with arms or explosives, against a person, group, community, or state that undermines people-centred security and/or sustainable development. Source

Violence that is directed against a person on the basis of gender or sex. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental, or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, or other deprivations of liberty. While women, men, boys and girls can be victims of gender-based violence, because of their subordinate status, women and girls are the primary victims. Source

IHL distinguishes between Non-international armed conflict defined as “A conflict in which government forces are fighting with armed insurgents, or armed groups are fighting amongst themselves” and International armed conflict defined as “A war involving two or more States, regardless of whether a declaration of war has been made or whether the parties recognize that there is a state of war. Source

A criminal act or acts intended to inflict dramatic and deadly injury on civilians and to create an atmosphere of fear, generally in furtherance of a political or ideological (whether secular or religious) purpose. Terrorism is most often carried out by sub-national or transnational groups, but it has also been known to be practiced by rulers as an instrument of control. Source

Research Office