The Morphology of Urban Conflict

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-gady-hk84During the Cold War, civil conflict had a rural bent, which research mirrored1. Urban environments were traditionally viewed as undermining identifications that provide an impetus for fighting2, too well protected as the home bases of elites and even prohibitive to rebel operations3. As the world population grows and increasingly clusters in urban spaces4, we argue that conflict will be redirected – whether purposefully or unintentionally – to cities. Results from several recent studies provide substantial support for a nascent urban propensity towards conflict – an emerging “urban shift”5.

One may attribute the shift to a number of factors. Cities are natural targets because of their political, economic, symbolic and logistical significance, which ensures that they are vital nodes to control in relation to trade, transportation and communications6.

Accelerated social and economic changes in cities cause political instability, inequality and unemployment, resulting in alienation, dislocation and the articulation of demands that previously would have been unthinkable. Crime is another major factor contributing to human insecurity in cities. It is contingent on opportunities for predation combined with low risk of incarceration8, and is often perceived as having become “the raison d’être of the new wars”9. Urban areas with high population densities also heighten the likelihood of geographically concentrated groups which are more prone to conflict than dispersed ones10. Part of the explanation is that proximity tends to enhance the opportunity and ability to mobilise, organise, and act collectively11, drawing on a bigger pool of recruits12. And groups can exploit state incapacity, large concentrations of disaffected youth and others with grievances, together with the physical features of urban areas13. The extreme cases are “feral cities”, i.e., sprawling metropolises with ineffective local government and negligible social services, where corruption, greed, and violence prevail and people have no way of escape14. It follows that cities are frequently the repositories of organised and unorganised violence by non-state actors as well as the state15.

The Lens of Urban Morphology

As armed conflict and violence shift to urban areas where a majority and growing share of the world’s population resides – a trend we expect to be more pronounced in the coming decade – the very nature of conflict is undergoing a transformation. The specific lens of urban morphology employed here accentuates the evolving interactions among the dimensions of structure, identity, control and conflict that alter the circumstances and influence the outcomes of urban conflicts, and affect one another in an endogenous manner.

- Structure. Essential to structure is the physical and demographic landscape. Cities vary in terms of size, scale and shape, reflecting different levels of accessibility or local/global integration, as well as different spatial signatures or “city fingerprints”16. In a related vein, residential settlement patterns in cities span the continuum from unified to partitioned17, with groups segregated by a single barrier to more exclusionary patterns of separation characterised by travel bans, unequal access, segregated roads, checkpoints, and nested enclaves.

- Identity. The concept of identity and its implications for conflict has come to occupy centre stage across the social, behavioural, and to a lesser extent, physical sciences18. While considering identity in the study of conflict and violence is widely accepted by now, determining which dimensions matter and how they assume salience is still very much a work in progress. Today’s conflicts are characterised by multiple groups, shifting allegiances, and resulting changes in group boundaries and balances. Identity complexity is further amplified in cities, where individuals navigate multiple dimensions of their identities in close proximity to a myriad of others, and where the distinction between civilian and combatant is increasingly blurred.

- Control. Complete territorial control is difficult to attain in urban areas. A monopoly of violence is necessary for control, as is support from civilian populations and the associated ability to identify and punish defectors. Regardless of whether rival political actors have short or long shadows of the future19, society effectively becomes a battlefield in the quest for control in cities – one whose contours are continually shaped and re-shaped by the number of rival actors, demographic profiles and residential settlement patterns, group allegiances, and the built environment.

- Conflict. In urban settings, multiple conflicts and forms of violence – spanning the gamut from crime to terror, protests, riots, and pogroms, to outright rebellion and warfare – can coexist. This “profile” can shift with changes in the urban landscape or be (re)framed to suit prevailing agendas, making interrelated events of this nature inherently difficult to record, let alone forecast with precision and reliability. As a consequence, the violence that exists in urban areas also varies, from selective to indiscriminate targeting, and includes extortion, kidnapping, sexual violence and homicide.

Cities as Sites of Conflict in the Syrian Civil War

The primacy of cities in the Syrian civil war is evident, with battles fought amongst a shifting constellation of armed organisations in Aleppo, Damascus, Idlib, Kobane, and Raqqa, as well as along key arteries connecting these centres to rural areas. Narratives of the conflict typically feature the Syrian Government, opposition, Kurdish forces and ISIS as the major armed actors, reflecting the conflict’s dominant political cleavages20. Yet, while the armed groups associated with each of these factions cooperate, at times forming organisations with routinised command and control structures, such alliances can be fragile21.

In urban centres like Aleppo, where numerous armed organisations such as the Free Syrian Army, Syrian Democratic Forces, ISIS, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Ahrar al-Sham, and the Syrian Government have vied for control of the city (Figure 2), civilians must cope with disconsonant governance regimes, while structural impediments make movement across zones of control difficult for inhabitants and humanitarian workers alike. Given the spectrum of ideological positions and variation in organisational capacity of these groups, small shifts in control over densely populated areas have disproportionately large consequences. Where armed actors attempt to establish political order, militants may not enforce these systems consistently, spreading uncertainty and terror among civilians. Competing groups may also use violence to prevent rivals from building sustainable governance structures. And dissent by civilians elicits a range of responses from the punishment of rule-violators to rewards that include the provision of public services.

The numerous armed groups competing for territory and civilian support has resulted in fragmented zones of control and violence in cities across Syria. Changes in group control have implications for settlement patterns, allegiances, and the spatial distribution of the conflict itself, as do changes in the built environment, which in turn re-shape patterns of control. It comes as no surprise, then, that over the past two years in Syria, civilians made up over 30% of total conflict fatalities, while 71% of civilian fatalities from remote violence occurred in populated areas22.

The Future of Armed Conflict in Cities

As cities emerge as the dominant sites for civil conflict, international organisations and governments are faced with situations that differ markedly from rural locales. For one, the humanitarian situation for civilians is likely to be dire23. The structure of densely populated cities makes collective punishment more probable as armed actors vie for control – inflicting casualties, disrupting rival attempts at governance, and destroying civilian-occupied buildings, enclaves, and infrastructure in the process. The inter-connectedness of urban services exacerbates the problem24. As the number of independent actors vying for control in an urban area increases, humanitarian access to these areas becomes decidedly more complicated, with emergency service provision often hinging on negotiations with competing factions or de facto recognition of violent political orders.

And even in cities where armed actors revive economic life and public services, it is difficult to distinguish between voluntary civilian support and forced compliance for fear of punishment. Where military authority over relatively unpopulated areas offers few opportunities for dissenters to act collectively, cities facilitate the emergence of micro-political orders, partially controlled by civilian actors. Moving forward, complete military, economic and social control over densely populated urban areas appears less and less feasible, even in the aftermath of civil conflict.

The heterogeneity of factors associated with urban conflict, including complex patterns of causation and interdependence, requires us to move beyond narrow categorisations and conceptualisations. In such systems, a single factor may change, but the intricate links between causal factors make the eradication of violence extremely difficult. In order to study the micro-dynamics of urban conflict, fine-grained data from multiple sources, including geo-coded, social media, and survey data, is required, as are methods to explore the interplay between structure, identity, control and conflict – the lens of urban morphology proposed here.

Notes

- Walter Laqueur, The Guerrilla Reader: A Historical Anthology (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1977).

- Monica Duffy Toft, The Geography of Ethnic Violence: Identity, Interests, and the Indivisibility of Territory (Princeton University Press, 2005).

- John Ellis, A Short History of Guerrilla Warfare (Ian Allan Publishing, 1975).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision,” ST/ESA/SER A/366, 2015, https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-report.pdf.

- Clionadh Raleigh and Håvard Hegre, “Population Size, Concentration, and Civil War: A Geographically Disaggregated Analysis,” Political Geography 28, no. 4 (2009): 224–38;

Robert Muggah, “Researching the Urban Dilemma: Urbanization, Poverty and Violence” IDRC, 2012), https://www.idrc.ca/sites/default/files/sp/Images/Researching-the-Urban-Dilemma-Baseline-study.pdf;

Margarita Konaev and John Spencer, “The Era of Urban Warfare Is Already Here,” FPRI’s (Foreign Policy Research Institute) E-Notes, 21 March 2018, https://www.fpri.org/article/2018/03/the-era-of-urban-warfare-is-already-here/. - Patrick O’Sullivan and Jesse W. Miller, The Geography of Warfare (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1983);

Gregory J. Ashworth, War and the City (London: Routledge, 1991);

Patricia O. Daley, Gender and Genocide in Burundi: The Search for Spaces of Peace in the Great Lakes Region (Indiana University Press, 2008). - Ralph Sundberg and Erik Melander, “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013): 523–32;

Croicu Mihai and Ralph Sundberg, “UCDP GED Codebook Version 17.1” (Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, 2017);

Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University, “Documentation for the Global Rural-Urban Mapping Project, Version 1 (GRUMPv1): Urban Extent Polygons, Revision 01” (Palisades: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC), 2017). - Keith Krause, Robert Muggah, and Elisabeth Gilgen, Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011: Lethal Encounters (Cambridge University Press, 2011);

Samuel P. Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968). - Derek Gregory, “War and Peace,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 35, no. 2 (2010): 154–86.

- Monica Duffy Toft, The Geography of Ethnic Violence: Identity, Interests, and the Indivisibility of Territory (Princeton University Press, 2005);

David D. Laitin, “Ethnic Unmixing and Civil War,” Security Studies 13, no. 4 (2004): 350–65;

Clionadh Raleigh and Håvard Hegre, “Population Size, Concentration, and Civil War: A Geographically Disaggregated Analysis,” Political Geography 28, no. 4 (2009): 224–38. - Nils B. Weidmann, “Geography as Motivation and Opportunity: Group Concentration and Ethnic Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53, no. 4 (2009): 526–43;

Paul Staniland, “Cities on Fire: Social Mobilization, State Policy, and Urban Insurgency,” Comparative Political Studies 43, no. 12 (2010): 1623–49. - Clionadh Raleigh and Håvard Hegre, “Population Size, Concentration, and Civil War: A Geographically Disaggregated Analysis,” Political Geography 28, no. 4 (2009): 224–38.

- Jennifer M. Taw and Bruce Hoffman, The Urbanization of Insurgency: The Potential Challenge to Us Army Operations (Minnesota Historical Society, 1994);

Gregory J. Ashworth, War and the City (London: Routledge, 1991);

Russell W. Glenn, Combat in Hell: A Consideration of Constrained Urban Warfare (Santa Monica: Rand Publishing, 1996);

C. Christine Fair, Urban Battle Fields of South Asia: Lessons Learned from Sri Lanka, India, and Pakistan (Rand Corporation, 2005);

Stathis N. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006);

Paul Brooker, Modern Stateless Warfare (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). - Richard J. Norton, “Feral Cities,” Naval War College Review 56, no. 4 (2003): 97–106.

- Stephen Graham, Introduction: Cities, Warfare, and States of Emergency (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004).

- Michael Batty, “The Size, Scale, and Shape of Cities,” Science 319, no. 5864 (2008): 769–71;

Bill Hillier, Alan Penn, Julienne Hanson, Tadeusz Grajewski, and Jianming Xu, “Natural Movement: Or, Configuration and Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement,” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 20, no. 1 (1993): 29–66;

Rémi Louf and Marc Barthelemy, “A Typology of Street Patterns,” Journal of The Royal Society Interface 11, no. 101 (2014): 20140924. - Ron Johnston, Michael Poulsen, and James Forrest, “The Geography of Ethnic Residential Segregation: A Comparative Study of Five Countries,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 97, no. 4 (2007): 713–38.

- Rawi Abdelal, Yoshiko M. Herrera, Alastair Iain Johnston, and Rose McDermott, “Identity as a Variable,” Perspectives on Politics 4, no. 4 (2006): 695–711;

Kristin M. Bakke, Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, and Lee J. M. Seymour, “A Plague of Initials: Fragmentation, Cohesion, and Infighting in Civil Wars,” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 2 (2012): 265–83;

Mart Bax, “Warlords, Priests and the Politics of Ethnic Cleansing: A Case Study from Rural Bosnia Herzegovina,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 23, no. 1 (2000): 16–36;

Ross A. Hammond and Robert Axelrod, “The Evolution of Ethnocentrism,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 50, no. 6 (2006): 926–36;

Stathis N. Kalyvas, “The Ontology of ‘Political Violence’: Action and Identity in Civil Wars,” Perspectives on Politics 1, no. 3 (2003): 475–94;

Stathis N. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006);

Kanchan Chandra, ed., Constructivist Theories of Ethnic Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). - Mancur Olson, “Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development,” American Political Science Review 87, no. 3 (1993): 567–76.

- Ben Hubbard and Jugal K. Patel, “Why Is the Syrian Civil War Still Raging?” New York Times, 8 February 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/02/08/world/middleeast/war-in-syria-maps.html.

- Fotini Christia, Alliance Formation in Civil Wars (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Clionadh Raleigh, Andrew M. Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen, “Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data,” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651–60;

Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University, “Documentation for the Global Rural-Urban Mapping Project, Version 1 (GRUMPv1): Urban Extent Polygons, Revision 01” (Palisades: NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC), 2017). - International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), “‘I Saw My City Die’: Voices from the Front Lines of Urban Conflict in Iraq, Syria and Yemen” (2017), https://www.icrc.org/en/download/file/46689/4312_002_urban-warfare_web_new_en.pdf;

Jennifer Dathan and James Kearney, “The Burden of Harm: Monitoring Explosive Violence in 2017” (2017), https://aoav.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Explosive-Violence-Monitor-2017-v6.pdf. - International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), “Urban Services during Protracted Armed Conflict: A Call for a Better Approach to Assisting Affected People” (Geneva, 2017), http://www.livelihoodscentre.org/documents/20720/25507/EN_2_1_1%20Urban%20Services%20in%20Proracted%20Armed%20Conflicts%20ICRC.pdf/a95e2d1c-b720-489c-9aac-75a06ae5f695.

———, “‘I Saw My City Die’: Voices from the Front Lines of Urban Conflict in Iraq, Syria and Yemen” (2017), https://www.icrc.org/en/download/file/46689/4312_002_urban-warfare_web_new_en.pdf.

Electronic reference

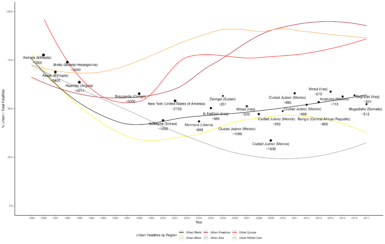

Reul, Mirko, and Ravi Bhavnani. “The Morphology of Urban Conflict.” Global Challenges, no. 5, April 2019. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/5/the-morphology-of-urban-conflict. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-gady-hk84.Map based on the data produced by the Small Arm Survey, and enriched by the Graduate Institute’s Research Office in Geneva, in collaboration with whybe.ch.

Migration, Violence and War, with Charles Heller

Graduate Institute – Research Office

State-Based Conflict since 1946

© ourworldindata.org / CC – Creative Commons

Source: Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)

Variable description: Ongoing conflicts are represented in each year in which more than 25 deaths occurred.

Violence, Killer Robots and Regulation, with Paola Gaeta

Graduate Institute – Research Office

Terminology Related to Violence and Conflict

The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.

The World Health Organization (WHO)

Derived from the Latin word conflictus, which means collision or clash. This term is understood as a disagreement between two or more parties through which the parties involved perceive a threat to their needs, interests or concerns. Source

A dispute involving the use of armed force between two or more parties, often referred to as war. Source

Militarised armed conflict between two or more states. Source

A conflict between a government and one or several non-governmental parties, often with interference or support from foreign actors.

The intentional use of illegitimate force (actual or threatened) with arms or explosives, against a person, group, community, or state that undermines people-centred security and/or sustainable development. Source

Violence that is directed against a person on the basis of gender or sex. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental, or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, or other deprivations of liberty. While women, men, boys and girls can be victims of gender-based violence, because of their subordinate status, women and girls are the primary victims. Source

IHL distinguishes between Non-international armed conflict defined as “A conflict in which government forces are fighting with armed insurgents, or armed groups are fighting amongst themselves” and International armed conflict defined as “A war involving two or more States, regardless of whether a declaration of war has been made or whether the parties recognize that there is a state of war. Source

A criminal act or acts intended to inflict dramatic and deadly injury on civilians and to create an atmosphere of fear, generally in furtherance of a political or ideological (whether secular or religious) purpose. Terrorism is most often carried out by sub-national or transnational groups, but it has also been known to be practiced by rulers as an instrument of control. Source

Research Office