The Future of Universities

VIDEO: The UNESCO Chair in Comparative Education Policy, with Chanwoong Baek

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute.

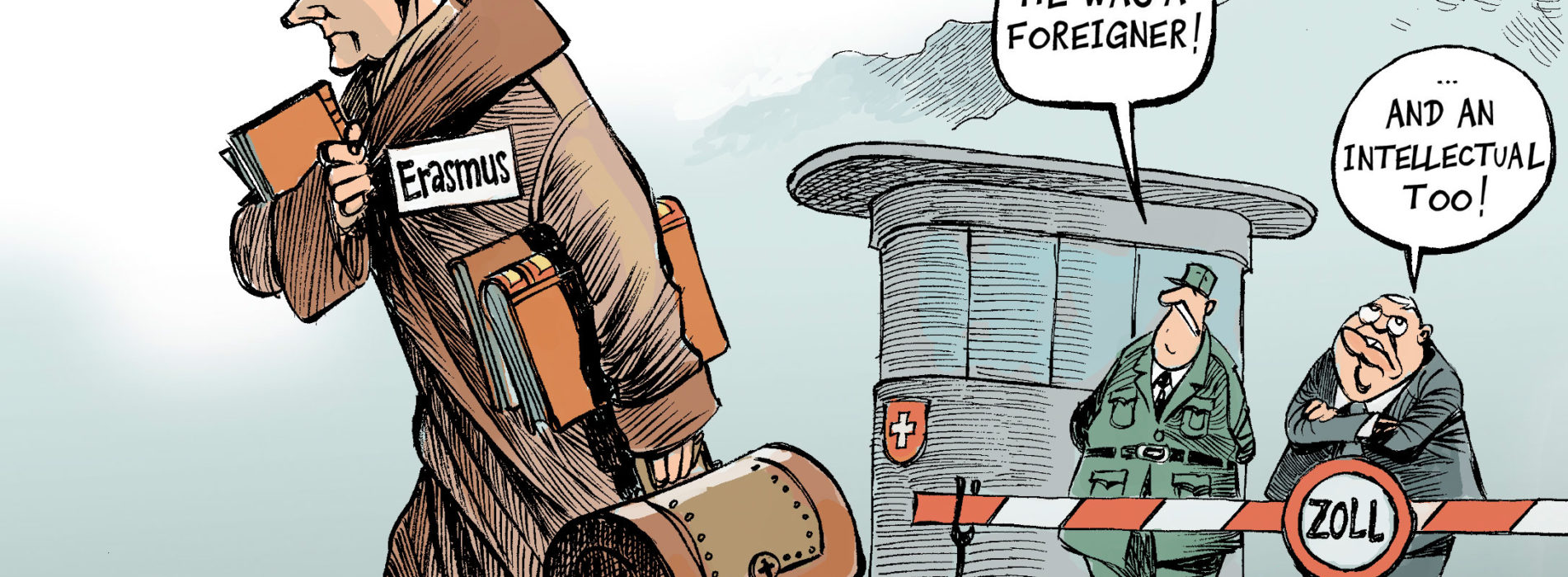

© Chappatte in Le Temps, Geneva

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute.

The multipolar world succeeding US hegemony in the early 21st century, the financial crisis of 2007 and the corollary decline of liberalism seem to have ushered in an era of economic nationalism. States are increasingly left to fend for themselves as multilateral mechanisms lose traction and international economic relations gain in toxicity. The sanctions, embargoes and retaliations arising from the war in Ukraine, but also an accelerating struggle for dwindling natural resources, have pushed these logics to new heights. This Dossier assesses ongoing geoeconomic transformations and their potentially devastating consequences.

The Dossier aims to explore new trends and expressions of violence in armed conflict in the 21st century. Taking as a starting point the changing paradigm of armed conflict – from conventional wars with clear contours towards more non-linear, fragmented and protracted types of civil and international conflict — it adopts a broad approach to portray changing forms of violence across different types of armed conflicts (including terrorism, international/civil wars or urban warfare). In the context of a fragmenting international order, with increasingly blurred lines between state and non-state, combatant and civilian, domestic and international, the number of actors involved in conflicts and concurrent strategies of violence have multiplied. In face of the ubiquity of violent conflict — despite an overall decline in interstate conflict and global number of casualties — the Dossier aims to shed light on new or changing forms of violence, their contexts, actors and victims. It explores the novelty, heterogeneity, scales and vectors of violent practices in contemporary conflicts by investigating the impact of a series of factors such as new military technologies (drones, robots), new communication tools (social media), gender, migration, or the subcontracting of security to private actors.

While the global balance of power, under the impetus of the steady rise of China, is shifting towards the Asia-Pacific, and because the future of US policy is uncertain after the election of Donald Trump, tensions in the South China Sea have once again become a major strategic concern. The South China Sea is witnessing a series of sovereignty disputes between littoral states defending rivalling claims to maritime rights and boundaries. Adding weight and urgency to the disputes are the significant natural resources found in the coveted archipelagos and sea beds as well as the rising national sentiments in many of the claimant states. The geostrategic dimension of these quarrels is largely transcending the region and the involvement of external powers such as the United States further complicates the equation. The recent legal victory of the Philippines over China can be seen as a supplementary cause for anxiety in a latent conflict that may at any time escalate into a regional or global confrontation. Henceforth the search for a negotiated solution becomes crucial as military budgets continue to soar in the region.