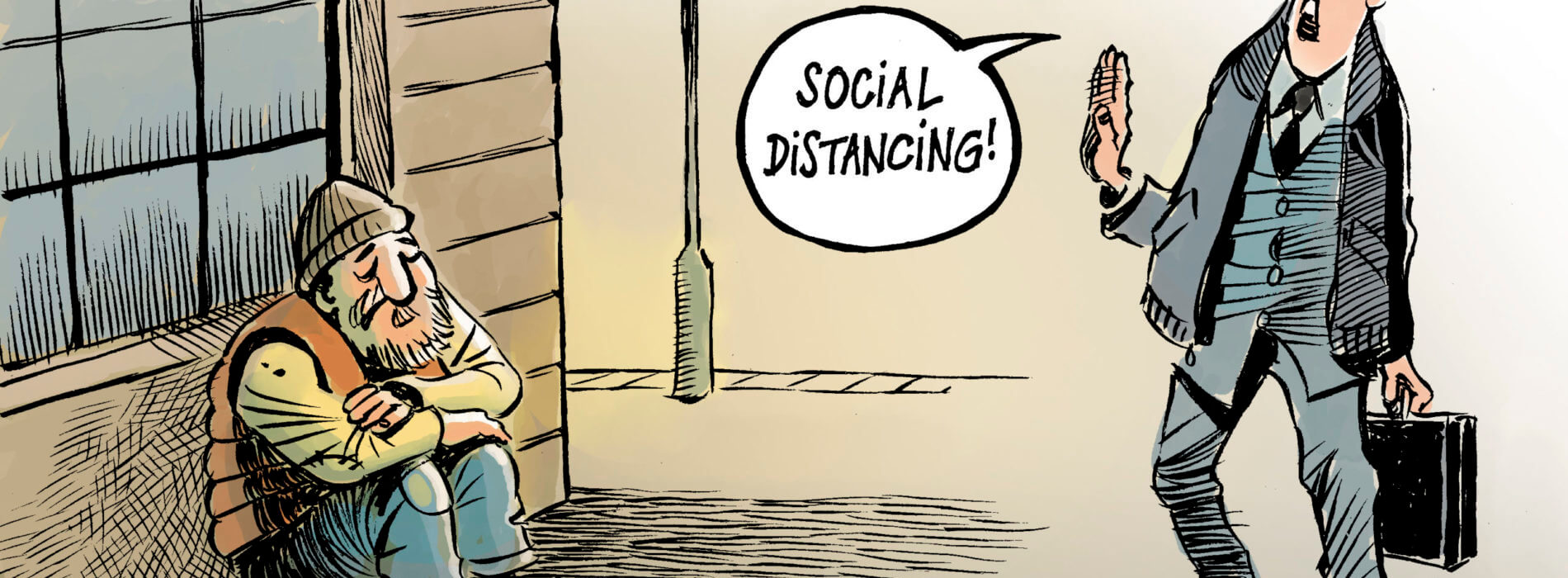

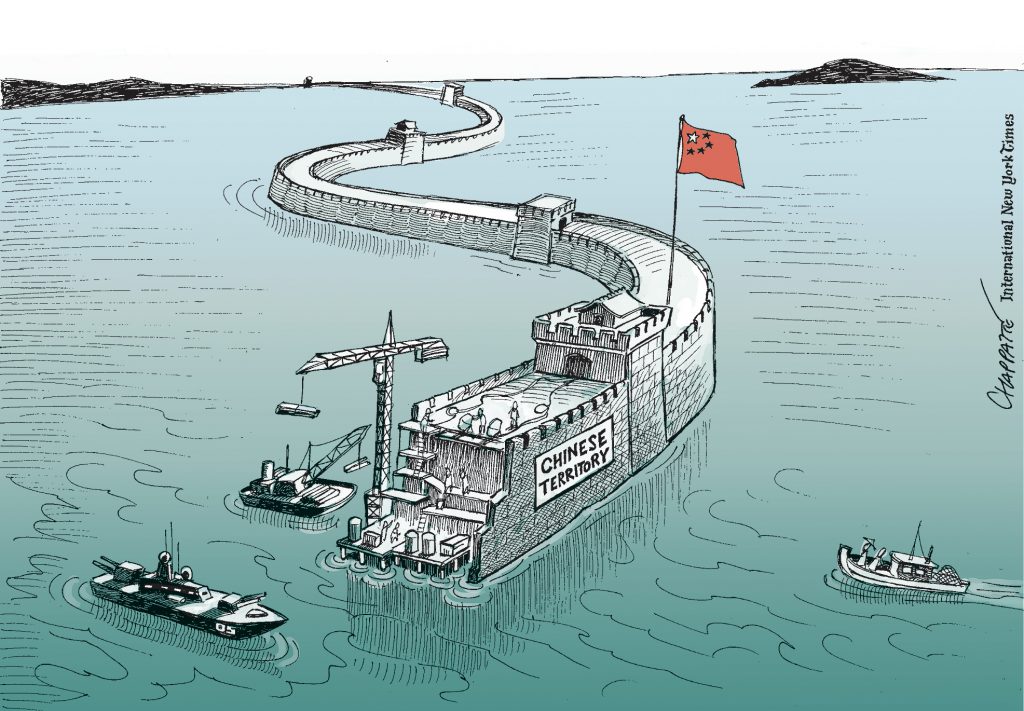

The Moving Fault Lines of Inequality

Debate on Inequality and the Social Contract

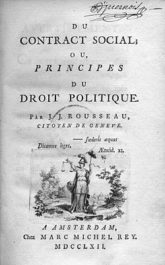

Liberty and equality entertain an uneasy and fraught relationship. How to reconcile the two has been one of political theory’s central quandaries. Proponents of radical approaches to political equality such as Rousseau have argued that equality may only come at the prize of providing a narrow – or positive – definition of freedom. An approach that has also been applied by the French revolutionaries who, most notably during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), applied a strict definition of what it meant to be free under republican conditions. Liberal proponents, on the other hand, have preferred a negative approach to freedom – privileging being free over being equal – by confining equality to law and reserving freedom to the private realm of individual expression. The radical impetus of equating being free to being equal may thus be opposed to the liberal impetus of equating being free to being different.

Political philosophers have further debated on whether inequality stems from history – or, as Rousseau suggests in his Second Discourse, from civilisation – and thus depends on human intervention or whether it is an inalterable anthropological constant. Liberals have argued the former, insisting that while inequality remains the norm in nature, it is mankind’s role to tame it through policies and laws (e.g., social contracts). Sociologists such as Gaetano Mosca and Robert Michels have come to the more sobering conclusion that elites are a quasi-permanent fixture of human societies and that, eventually, a minority of actors would come to dominate all political systems, even democracies. John Rawls, finally, proposed an elaborate theory of social justice arguing that the social contract needs to guarantee at once fundamental rights to individuals, equality in terms of opportunities, and that economic inequality is justified only to the extent that it serves to improve the lives of the worst off through redistributive mechanisms.

For further reading:

Jeff Manza, “Political Inequality”, in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, ed. Robert Scott and Stephen Kosslyn (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015): 1–17.