The Enduring Inequities of Racism

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-qhr8-ph95Ceaselessly breeding asymmetry, racism dwells in the intangibles of existence and experience.

Racial prejudice is quintessentially synonymous with unequal treatment. As a system, racism is predicated on the establishment of imbalanced socioeconomic relations. Perpetuated by asymmetrical political rules of interaction – often explicitly or implicitly reinforced by hampering legal structures and neutralising jurisprudence – mechanisms of bias are embedded in injustice, which they also further. Untangled in this way, racism and inequality become near-indissociable vectors of variegated and layered dispossession. With the passage of time, racial constructs and racist realities pass on generationally, problematically compounding their pernicious and lasting effects.

Linking status and opportunity, racism also moves to justify inequalities. It forcefully articulates a worldview that alternatively rationalises existing disparities in terms of racial, ethnic, cultural, economic or religious preference or seeks to translate them operationally in a political economy of otherness (extending it to all realms of communal and individual difference). Impressed this way, racial inequality should not, however, be quantified solely in economic terms or per the obvious denial of opportunities of livelihood (such as housing, employment, access to services and mobility). Racism dwells, importantly, in the intangibles of existence and social experience – intimate spaces of inequality whose violence is as acute as the one playing out at the more visible, less private surface. With consistency and endurance, bias speaks a language of inequality of being, seeing, doing – and crucially of not allowing. If racism is endemic, it is because it wields this multiplicity of calculated actions with an expected result, alignment with existing processes and neutralising of transforming possibilities.

Racism also shares an incestuous life with concealment Racism also shares an incestuous life with concealment. Though this may seem surprising given the oft-ideologised public expressions of racism, it is not completely so when the core logic of racism is seen for what it is, namely an organising device designed to produce societal imbalance. Naked, in-your-face prejudice being difficult to countenance systemically in the long run (e.g., slavery, segregation and apartheid), racism’s unwieldiness is remedied by tricks of the trade, hiding it in plain sight. These run the gamut from the “evolutionary models” or “civilisational ladders” peddled by many a “great mind” of the Enlightenment and the modern era to the hidden racialised securitisation of the early twenty-first century. All along, two traits recur in the form of instrumentalisation – of science, law and class as noted, but as well of predispositions, patterns and inclinations – and weaponisation, notably of systems, politics and, today as yesterday, imagery and discourse.

Ever rationalised, instrumentalised and weaponised thus, the replenishment of inequality is – conversely – fundamentally enabled by a deliberate distortion of the drivers of equality. The very repetitive nature of everyday status quo allows those benefiting from it to evade its questioning, painting efforts to redress variance, such as the removal of statues of slave owners, as troublesome “techniques of cancellation”. Even in the post-Black Lives Matter world, diversity is frowned upon (paid lip service to but often processed by human resources as, a decade ago, banks dragged their feet on compliance requirements). Statues of slave-owners are indeed defended in the name of a self-serving (mis)understanding of history. The tables are turned, as illustrated by accusations of reverse discrimination made to antiracists denouncing the continuity of systemic preference. The mainstreaming of such techniques – witness the efflorescence of antipolitical correctness – is primarily illustrative of agile privilege-wielding.

When it comes to racism, inequality has nine lives When it comes to racism, inequality has nine lives. The wherewithal of prejudice lodges itself too easily in the impersonal structures of institutions and the cowardice of bureaucracy, in the language of phony science and the unshakable Eurocentrism of academia, in the geographies of dangerousness and the criminalisation of “the other”, in the political immunisation of some cultures and the policing of others and in the usurping of health regimes. Each new era – as the persistence of racism is revealed, time and again – allows remixed social contexts to be skewed in alignment with misalignment. Thus, the quaint opportunities of globalisation’s “information superhighway” gave way to algorithms of oppression, and instead of disappearing, borders found new life birthing myriad new ways for racism to speak to itself across time and space only to deny the crossing of such lines.

If contemporary racism is arguably more problematic than earlier configurations, it is because it has subsumed these already-complex historical lines, synthesising them by simultaneously overtly discriminating, covertly denying, systematically targeting and systemically preventing advancement. The plethora of possibilities for inequity and iniquity to coexist continuously speaks, in the final analysis, of the historical and global weight of hierarchy and the patterns of interaction derivative from it. The issue is not reinvigorated populism, illiberal ideologies or chaotic social media but rather, more profoundly, the endemic requirements of social orders that seem to cultivate difference, nurture dichotomies and invite ranking – unable or unwilling to transcend such tropes.

Electronic reference

Ould Mohamedou, Mohammad-Mahmoud. “The Enduring Inequities of Racism.” Global Challenges, no. 9, March 2021. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/9/the-enduring-inequities-of-racism. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-qhr8-ph95.PODCAST: Inégalités, anthropologie et développement – Gilbert Rist

Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST: Inequalities and Humans Rights – Irene Khan

Graduate Institute, Geneva

RESEARCH DOCUMENTARY: Inequality and Conflict – Beyond Us and Them

Realised and financed by the the FNS, and strongly supported by the Gender Centre (Graduate Institute, Geneva), this research documentary film is the result of a participatory filmmaking process and presents three projects conducted in Guatemala, Nigeria, Sri Lanka and Indonesia within the Social Conflicts module of the Swiss Programme for Research on Global Issues for Development (r4d programme). It features the research context and findings of the Gender Centre’s project “The Gender Dimensions of Social Conflicts, Armed Violence and Peacebuilding”.

TV NEWS: Hustlers vs Dynasties: Experts Warn Kenyans against the Narrative

The Youtube NTV Kenya channel

Thomas Piketty and the Inequality Economists

Thomas Piketty at the reading for Capital in the Twenty-First Century on 18 April 2014 at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

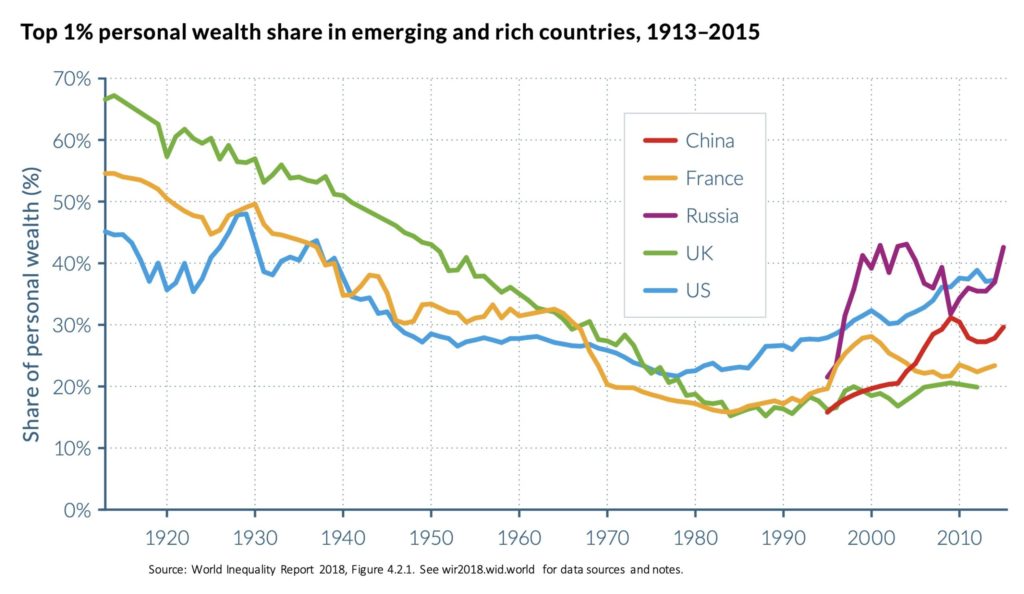

Thomas Piketty at the reading for Capital in the Twenty-First Century on 18 April 2014 at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge, Massachusetts.Over the last decade, a vivid scholarly debate over the issue of inequality and its drivers has taken place among economists and attracted a lot of public attention. It includes, most prominently, Thomas Piketty and other French economists such François Bourguignon, Thomas Philippon, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman but also Anglo-Saxon scholars such as Anthony Atkinson, Joseph Stieglitz and Branko Milanovic. Piketty landed an Amazon’s best-seller with his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014), in which he argues that welfare states and social policies are the exception in history while the general tendency under capitalist conditions is for inequality to rise as the returns to capital are greater than the general rate of economic growth. Piketty therefore opposed previous theories, such as Simon Kuznets’ U-shape model assuming that under capitalism inequality first rises to subsequently decline with the apparition of redistributive mechanisms and policies. From Piketty’s perspective, the “egalitarian” decades from the 1930s to the 1970s, while constituting an exception, also prove that economic inequality is not predetermined but may be acted upon through political and social measures. Others such as Branko Milanovic have argued for more cyclical approaches to inequality, suggesting that it is sporadically checked by wars, plagues and demographic disruptions that are exogenous to the market.

Further readings:

- Robert H. Wade, “The Piketty Phenomenon and the Future of Inequality”, real-world economics review, no. 69 (7 Oct. 2014): 2–17.

- Mike Savage, “An Interview with Thomas Piketty, Paris 8th July 2015”, Working Paper no. 1, International Inequalities Institute, LSE, September 2015.

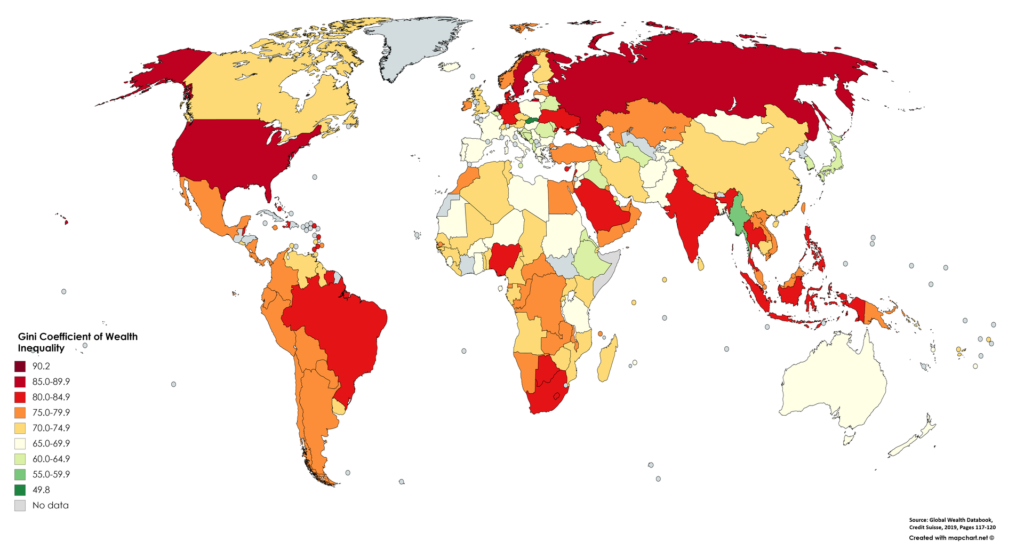

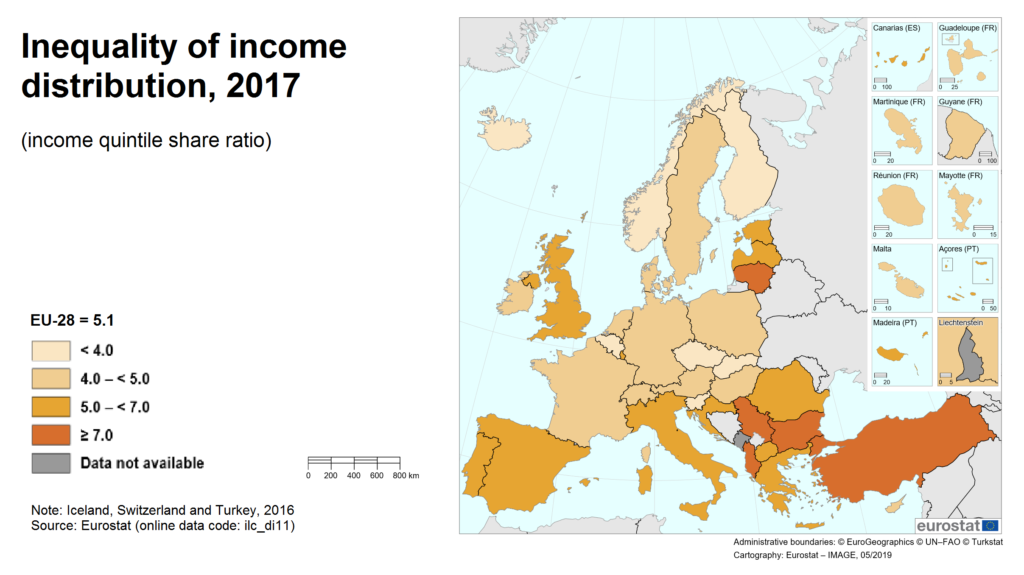

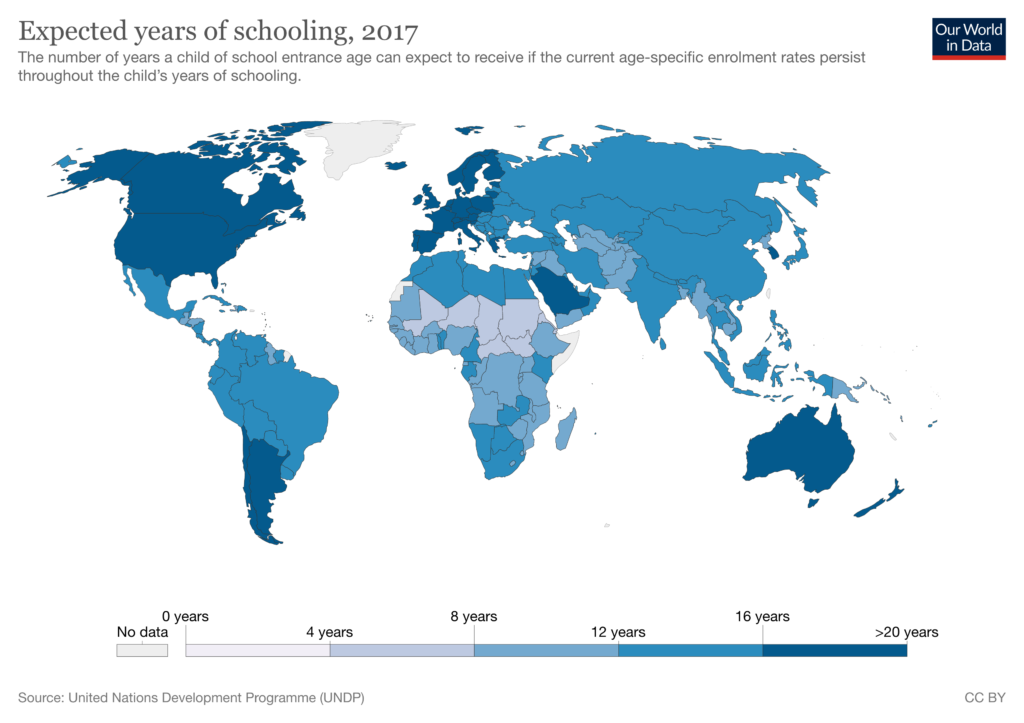

Measuring Inequality

Inequality measurement can take many forms. Depending on what kind of inequality is being measured (economic, health, education, etc.), different types of indicators will be used (revenue, wealth, average years of schooling, life expectancy…). Measuring inequality further depends on the units of measurements (individuals, households, tax-paying units, etc.) and the types of entities/groups that are being compared. Measuring inequality across country or regions thus differs from measuring inequality within a given society (e.g., between specific segments of a given population) or between citizens globally.

Gini Index

The most common index to measure economic inequalities in terms of revenue or wealth is the Gini coefficient. It measures the extent to which the distribution of income across a society deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. It is based on the Lorenz curve, which represents the cumulative proportion of the population on the horizontal axis and the cumulative proportion of income on the vertical axis. If one person earned all income (maximum inequality) the Gini coefficient would be equal to 1. If income was shared equally between all, the Gini coefficient would equal 0.

Palma Index (or Ratio Measures)

Ratio measures compare how much revenue or wealth is held by a specific segment of the population as compared to another. They allow to adjust for the Gini index’s oversensitivity to changes in the middle of the distribution. The Palma ratio, for instance, measures the share of national income of the top 10% compared to that hold by the lower 40%. In more equal societies this ratio will be 1 or below but in very unequal societies it might go up to 7.

Theil Index

Theil indexes, finally, measure inequality in terms of how wealth or revenue is spread among different regions (e.g. urban and rural).

For further reading:

- UNDESA, Inequality Measurement, Development Issues no 2, 21 October 2015

- GSDRC, “Measuring Inequality”

Debate on Inequality and the Social Contract

Liberty and equality entertain an uneasy and fraught relationship. How to reconcile the two has been one of political theory’s central quandaries. Proponents of radical approaches to political equality such as Rousseau have argued that equality may only come at the prize of providing a narrow – or positive – definition of freedom. An approach that has also been applied by the French revolutionaries who, most notably during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), applied a strict definition of what it meant to be free under republican conditions. Liberal proponents, on the other hand, have preferred a negative approach to freedom – privileging being free over being equal – by confining equality to law and reserving freedom to the private realm of individual expression. The radical impetus of equating being free to being equal may thus be opposed to the liberal impetus of equating being free to being different.

Political philosophers have further debated on whether inequality stems from history – or, as Rousseau suggests in his Second Discourse, from civilisation – and thus depends on human intervention or whether it is an inalterable anthropological constant. Liberals have argued the former, insisting that while inequality remains the norm in nature, it is mankind’s role to tame it through policies and laws (e.g., social contracts). Sociologists such as Gaetano Mosca and Robert Michels have come to the more sobering conclusion that elites are a quasi-permanent fixture of human societies and that, eventually, a minority of actors would come to dominate all political systems, even democracies. John Rawls, finally, proposed an elaborate theory of social justice arguing that the social contract needs to guarantee at once fundamental rights to individuals, equality in terms of opportunities, and that economic inequality is justified only to the extent that it serves to improve the lives of the worst off through redistributive mechanisms.

For further reading:

Jeff Manza, “Political Inequality”, in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, ed. Robert Scott and Stephen Kosslyn (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015): 1–17.