Arts and the Study of the International

More on my ethnography of the Tubas Cluster Plan, by Dorota Kozaczuk

My ethnographic study of the Tubas Cluster Plan dates back to 2016, when the Palestinian consultancy CEP (Center for Engineering and Planning) began developing a regional master plan for the Tubas Governorate in the northern Jordan Valley. The project covered 118,297 square kilometres, including lands within the 1940 village boundaries of Tayasir and Bardala, as well as northern sections of Area C within Tubas city limits. Nine Palestinian communities were included in the planning framework: Al Malih, Ein al Hilwa, ‘Aqqaba, Tayasir, Khirbet Tell el Himma, Ibziq, Kardala, ‘Ein el Beida, and Bardala.

At the outset, the CEP team compiled available GIS maps, updated aerial photographs, and gathered archival data from Palestinian ministries and municipal authorities. They collaborated with a Belgian NGO and UN-Habitat as part of the project “Fostering Tenure Security and Resilience of Palestinian Communities through Spatial-Economic Planning Interventions in Area C (2017–2020).” Consultations were held with village mayors and governorate representatives, following participatory planning protocols developed by GIZ and the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government.

By 2019, during my participant observation in CEP’s Ramallah offices, four planning options had been prepared. I was shown the preferred version and invited to meetings where it was presented to stakeholders.

Aesthetic Vision and Political Friction

The Tubas Cluster Plan was visually compelling. On a printed A1 sheet, the region was divided into three zones: a deep green western section for agriculture, a faint brown central zone for mountainous terrain, and a dull green eastern area for pastoral land. Seven small zones, marked in vivid orange and bordered in blue, represented planned communities in the north, west, and east. CEP staff noted that the Israeli Civil Administration had approved plans for Tayasir, ‘Ein el Beida, and Bardala, while previously rejected plans for Al ‘Aqaba, Al Malih, Al Farisyia, and Karbala had been redesigned.

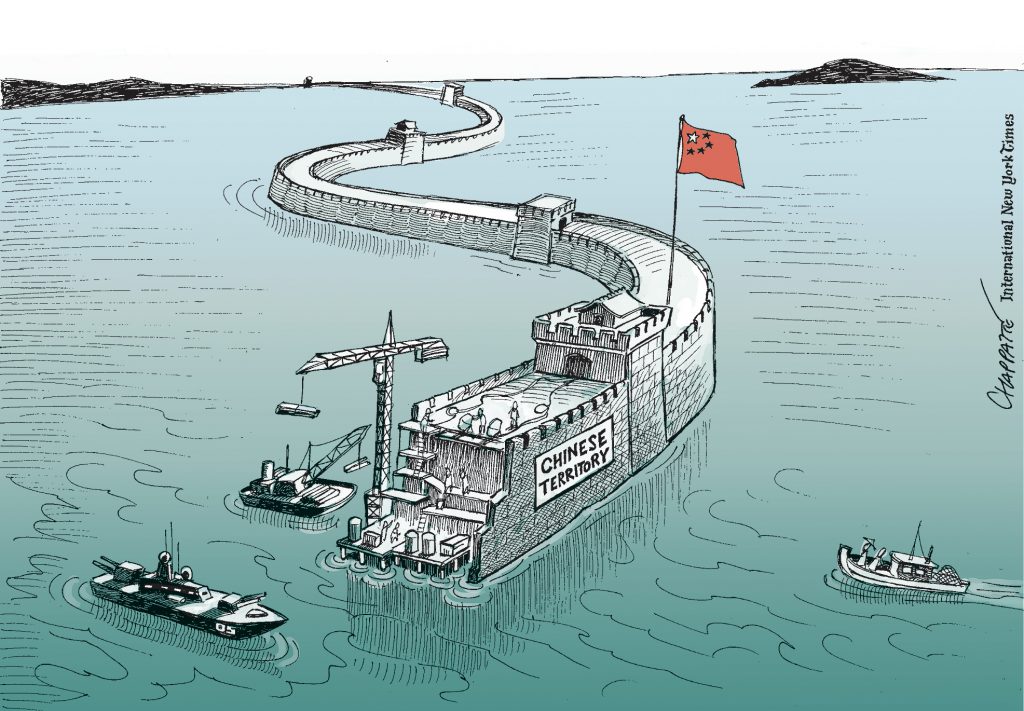

The plan proposed a road encircling the mountain range, connecting the seven communities, and included upgrades to existing roads in the west and south. Notably, it omitted Israeli settlements, the separation wall, and the military designation of much of the area. In this orthographic vision, the region functioned holistically for Palestinian life, with orchards and livestock populating the mountains and tourist routes inviting exploration. The Tubas Cluster Plan was both a misrecognition of occupation and an assertion of Palestinian reality—true to its survey methods, logically deterministic, and far from naïve.

Between Aspiration and Constraint

Shortly after my study, CEP submitted a report with four proposals to UN-Habitat, the Ministry of Local Government, and the Tubas Regional Committee. I attended the unveiling at the Palestinian Ministry of the Wall and Settlements. The meeting aimed to align institutional goals, but quickly revealed tensions. Ministers and engineers spoke of life near the Occupation Wall and recounted stories of displacement. One minister criticized the plan as disconnected from lived realities and questioned its aesthetics. A planner, however, defended the right to imagine beyond oppressive facts, arguing that the Tubas visualisation offered a glimpse of what that could look like.

The meeting ended without consensus. Ministerial support for a plan covering large swaths of Area C carried serious political implications: it risked undermining the Oslo Accords and provoking backlash from Israel and the international community. The plan’s aesthetic of misrecognition also conflicted with the prestige of “surveyed oppression,” which underpins legal and humanitarian support for Area C. In reality, Tubas remained a zone of daily survival under Israeli fire.

Weeks later, the CEP team presented the plan to the nine communities. At the Tubas Municipal Offices, the idea of a prosperous region was met with quiet resignation. It was deemed unachievable and received little attention.

By the end of the following month, CEP submitted individual village plans to the Israeli Civil Administration, aiming to expand them beyond Area B. These plans conformed to the aesthetics mandated by the ICA—complete with its loathed colour scheme and the infamous blue polygon.

By autumn 2019, CEP confirmed that the Tubas Cluster Plan had not been approved.