Orbán’s Lawfare against Liberal Democracy in Hungary

“Democratic” decision making is a means for finding and implementing the will of the majority; . . . it serves, not to encourage diversity, but to prevent it.Established with funding from the Hungarian-born US billionaire George Soros, professors of the CEU were recently reviled as “officers of an occupying army” by Péter Harrach, a former minister belonging to the ruling party. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán embodies the reactionary populist politics that is gaining ground in many parts of Europe and the world. In a well-publicised speech in 2014 he declared with pride that Hungary was an “illiberal state”. He subsequently asserted with obvious pride that the Trump revolution happened in Hungary, the country that led the global backlash against liberalism. In a bid to position himself as a leader of the European People’s Party (EPP) in the European Parliament, Orbán reinforced his antiliberal credentials by recently asserting, “Christian democratic parties in Europe have become un-Christian: we are trying to satisfy the values and cultural expectations of the liberal media and intelligentsia.” He added, “Twenty-seven years ago here in central Europe we believed that Europe was our future; today we feel that we are the future of Europe.” Extolling the virtues of the nation, church and family, Orbán has positioned himself as the defender of Christian Europe against hordes of Muslim migrants.Orbán has positioned himself as the defender of Christian Europe against hordes of Muslim migrants. With Orbán taking a leaf out of Putin’s authoritarian book, and Poland currently modelling itself on the Hungarian erosion of a separation of powers, one may well ask if illiberal democracies are there to stay in Central Europe.

This would have seemed an improbable scenario in 1989 when Hungary ruptured the Iron Curtain to set in motion the transition in Eastern and Central Europe towards democracy and a market economy. Yet by 2000 there was a discernable shift to a rhetoric of economic nationalism in Orbán’s party’s pronouncements followed by legal measures to roll back market reforms. Between 2010 and 2013 the government he led enacted some 700 laws, many of which reversed unpopular economic policies: property rights were selectively whittled away, foreign-controlled private pension funds renationalised, high taxes levied on the foreign-investment-heavy banking and energy sectors, and vast tracts of EU-subsidised agricultural land redistributed to party functionaries. The new policies, which initiated a massive recentralisation of economic and political power, were explicitly devised to benefit domestic businesses with close ties to the ruling Fidesz Party. Analysing this systematic concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small coterie of family and party officials loyal to the leader, the former Hungarian Minister of Education Bálint Magyar has termed Hungary a “mafia state”.

The legalisation of the illiberal state through lawfare

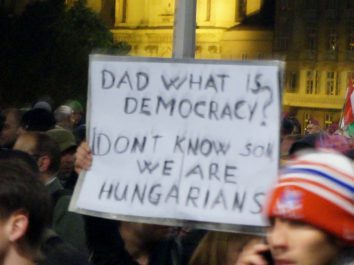

“Dad what is democracy?” Protest against the right-wing Orbán-government and its imposed internet tax in Budapest, Hungary. 28 October 2014.

“Dad what is democracy?” Protest against the right-wing Orbán-government and its imposed internet tax in Budapest, Hungary. 28 October 2014.The systematic subversion of checks and balances has followed a careful design to legalise the illiberal state through “lawfare” – passing legislation ad hoc, or in reckless piecemeal fashion without public scrutiny or legislative deliberation. First, a new constitution was enacted that weakened all checks on majoritarianism. Next, the system for nominating judges to the Constitutional Court was altered to subvert the independence of the judiciary. Then, the electoral framework was changed to make it impossible for any other party except the ruling Fidesz to win. The National Election Commission was brought under Fidesz control making it impossible for civil society to organise referenda challenging government policies. Further, by appointing only high Fidesz officials to the office of the President, Orbán ensured that presidential powers would not be used to either return a law to Parliament for revision, or send it to the Constitutional Court for review. Finally, new laws were enacted that now guarantee strong political control of all media. Manned exclusively by Fidesz loyalists, the media regulatory agency has effectively curbed freedom of expression. At their own peril can the European Union (EU) and EPP continue to turn a blind eye to this travesty of the “rule of law” that transforms it into illiberal “rule by law”.The proportion of government wins in sensitive cases after it replaced judges in Constitutional Court increased by 250% since 2010

academic freedom in jeopardy

A new law assaulting academic freedom, pushed through Parliament in unseemly haste in April 2017, threatens the very existence of the cosmopolitan CEU. The law requires the CEU to maintain a campus in New York, where it is registered, a condition almost impossible to fulfil within the period stipulated by the government. While the Hungarian president signed this discriminatory legislation immediately, the Constitutional Court has yet to review it as called for in a petition by the CEU and all the opposition parties in the Hungarian parliament. Although targeting the CEU alone, the law is of a piece with the systematic erosion of the autonomy of all universities in the country. Hungary has seen state expenditure on higher education systematically decline since 2010, with a reduction of 25% between 2010 and 2013. Since 2006, the country has spent less and less on education, both in real terms and as a percentage of the GDP. Among OECD countries only Mexico and Turkey spend less. Large funding cuts at all Hungarian state universities created serious budget deficits that paved the way for a financial state of exception tailor-made for the installation of government-nominated “chancellors” at each university. Many are former Fidesz functionaries tasked with making financial and managerial decisions, who also exert political control and determine academic appointments. There was an alarming decline in student applications and enrolment, which fell by 24% between 2010 and 2014 and by a staggering 45% in 2016 alone (from 160,000 to 110,000).

These measures are part of deliberate policies intended to block avenues of social mobility within Hungary as well as to restrict opportunities for students to study abroad by changing rules for access to the Bologna system in the state universities. The government is committed instead to a nationalisation of science under its own political control. To this end, it founded and generously endowed the National University of Public Service, a training ground for the new cadres of the regime. The governor of the Hungarian National Bank has, tellingly, received permission to utilise the Bank’s public resources to establish a new economics university in his hometown, whose curriculum includes his own theories. All these developments have not only resulted in some 600,000 of the better-educated citizens to exit the country in the past four years, but also given them little incentive to return. Their votes are absent in Hungarian elections just as their voice is now missing from domestic political debate. Encouraging emigration can thus become an avenue to eliminate unwelcome critics.Encouraging emigration can thus become an avenue to eliminate unwelcome critics. But liberal democracy cannot survive in the absence of a diversity of opinions, free public debate and spaces of dissent, which autonomous universities provide. It also needs to be bolstered by the existence of strong, financially independent counter-majoritarian institutions, which can advocate even unpopular positions, free of political stranglehold. The 70,000 demonstrators marching through Budapest in support of the CEU last April clearly recognised this as they chanted “Free country, free university”, while the state television ignored the protest completely, broadcasting instead a programme praising fishing in Hungary.

The responsibility of the European Union and the European People’s Party

Democratisation is evidently not the linear, teleological process that modernisation theory, and its reincarnation, the postcommunist transition paradigm, would have us believe. Nor is democracy inevitably coupled with liberalism. The EU may be in no position to influence the course of illiberal, majoritarian, elected regimes in Russia, India, Venezuela, or the United States. But whether illiberal democracies take root in Europe will depend in large measure on whether the EU and the EPP continue to tolerate with impunity Viktor Orbán’s calling into question fundamental values of the EU such as human rights and freedom of thought while undermining civil and political liberties in Hungary. Reactionary ideologies and authoritarian practices often take root as much due to their popular appeal in times of crises as to the opportunism and hypocrisy of their liberal opponents.

Constitutional Court : Consensus vs. Gov-Nominated Judges

Source: democracy-reporting.org (September 2017)

Definitions of Democracy

Democracy can be defined as, literally, the rule by the people. The term is derived from the Greek dēmokratiā, coined from dēmos (“people”) and kratos (“rule”) in the 5th century BCE. At heart, democracy is based on three principles: popular sovereignty, political participation and political contestation. Democracies may take on different constitutional forms (constitutional monarchy, republic) and modes of territorial organisation (unitary, federal).

The ballot box (free, fair and regular elections) defines democracy at its most basic. This minimalist or “thin” conception of democracy can be opposed to a more substantial or “thick” definition holding that in addition to elections, democracy needs to satisfy a series of further constitutional, liberal and/or social criteria.

In a direct democracy the people govern sovereignly by congregating in popular assemblies and taking decisions by popular vote (usually by show of hands, as in the Swiss cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus). There is no political representation. For thousands of years direct democracy remained the principal model of democracy as exerted in city-states or other small-scale polities.

Example: ancient Athens.

A representative or electoral democracy is a type of democracy where the people govern indirectly through elected representatives. It requires a set of political institutions different from those of direct democracy such as parliaments and regular elections. Representative democracy became prevalent in the 19th century with the emergence of large nation-states.

Liberal democracy is a subgenre of representative democracy defined not only by free and fair elections, but also by the rule of law, the separation of powers and the protection of basic civil liberties (freedom of speech, assembly and religion). Liberal democracies limit the exercise of executive power and majority rule through constitutions ensuring independent courts, the protection of minorities, and basic human rights.

Semidirect democracy is a mixed form of democracy where elected representatives govern and legislate but the citizens remain sovereign through referenda, initiatives and recalls. Even though today only Switzerland is a semi-direct democracy in the formal sense, many democracies have institutionalised elements of expression of popular will such as referenda.

Parliamentary democracy is a type of representative democracy where the executive branch of government depends on the support of the parliament, often expressed through a vote of confidence. The party that wins the largest number of congressional seats selects the prime minister, who controls the legislative process. The executive is divided into a head of government and a ceremonial head of state.

Examples: Australia, Germany, India, Spain.

Presidential democracy is a type of representative democracy where the executive branch is elected separately from the legislative branch. The parliament controls the budget, legislates, approves appointments to cabinet positions and ratifies foreign treaties. The president appoints cabinet members, commands the army and serves as the head of state and the head of government.

Examples: Argentina, Indonesia, United States, Venezuela.

Semi-presidential democracy is a type of representative democracy where a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet. It differs from the parliamentary system in that it has a popularly elected head of state, who is more than a purely ceremonial figurehead, and from the presidential system in that the cabinet, although named by the president, is responsible to the legislature, who can move a motion of no confidence.

Examples: France, Russia, Tunisia.

Participatory democracy refers to a regime where citizens participate actively in public decision-making. Instruments to broaden citizen participation include e-democracy and e-voting.

In a deliberative democracy authentic deliberation, not mere voting, is the primary source of a law’s legitimacy. Jürgen Habermas has made a fundamental contribution to deliberative democracy through his work on communicative rationality and the public sphere.

In a proportional system parties obtain seats proportionally to the votes they win. In a plurality system, candidates who win most votes in an electoral district are elected. In a majority system, candidates who win more votes than all others combined in an electoral district are elected. Proportional representation usually leads to a multiparty system whereas plurality and majority election favour bipartisanism.

United States

Russia

Uganda

Hungary

Turkey

Venezuela

This table shows the evolution of democracy in the USRussiaUgandaHungaryTurkeyVenezuela over 10 years. Arrows indicate the improvement (↗) or deterioration (↘) of a given indicator between 2006 and 2016. One arrow per 0.4 variance on a scale of 10.

| Aspects of democracy | Trend |

|---|---|

| Legislative constraints on the executive | ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘↘ ↗ |

| Judicial constraints on the executive | ↘ = ↗ ↘ ↘↘ ↘ |

| Government censorship (internet) | ↘↘ ↘ = ↗ ↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

| Government censorship (media) | ↘↘ ↗ = ↘↘ ↘↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

| Freedom of association | ↘ ↘ ↗ ↗ ↘ ↘ |

| Freedom house rule of law | ↘ = ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘ |

| Freedom of academic and cultural expression | ↘↘ ↘ ↘ ↘↘ ↘↘↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

Caricature de @Chappatte - www.chappatte.com Caricature de Beatriz Tirado

Source: Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit, EIU)

What Is Illiberal Democracy?

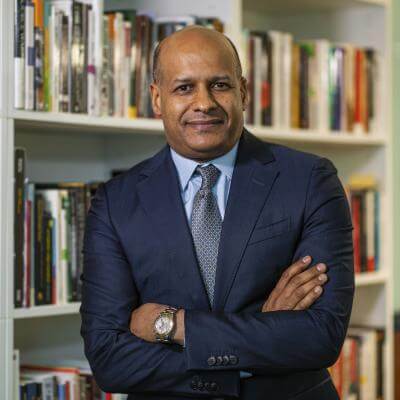

In his 1997 contribution to Foreign Affairs, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Fareed Zakaria defines illiberal democracies as “democratically elected regimes, often ones that have been reelected or reaffirmed through referenda, [but] are routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving their citizens of basic rights and freedoms”.

Fareed Zakaria is an Indian American journalist and author with a BA from Yale College and a PhD in Government from Harvard University. He worked as Adjunct Professor at Columbia University and as managing editor of Foreign Affairs from 1992 to 2000 (a post he was appointed to at only 28 years old). Zakaria has also been a columnist and editor for Newsweek, Time Magazine and The Atlantic. Currently he hosts Fareed Zakaria GPS – CNN’s flagship international affairs programme – and writes columns for The Washington Post. Foreign Policy named Zakaria one of its top 100 global thinkers. He is the author of five books, including The Future of Freedom (2003), The Post-American World (2008) and In Defense of a Liberal Education (2016).

- Consolidation of power in the executive

- Charismatic leader

- Erosion of the independence of the judiciary

- Weakening status of the parliament

- Recourse to direct democracy (plebiscites/referenda)

- Populist rhetoric/propaganda

- Discrimination of minorities

- Monitoring and moulding of civil society

- Media and internet censorship

- Curbs on academia and educational curricula

- Targeted repression of opponents

- Restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly

- Disregard for rule of law and human rights

- Misuse of state resources (cronyism)

- Emasculation of the electoral process

- Forging of external enemies

Illiberal democracy as a concept has been criticised for its diffuse meaning and close proximity to related, almost synonymous terms, such as: limited democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regimes, dysfunctional democracy, deconsolidating democracy, defective democracy and electoral authoritarianism. According to Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, the concept does not distinguish sharply enough democracies which have, in fact, never been truly democratic but claim to be so, from regimes that actually have successfully become or transitioned toward genuine democracy but are backsliding toward autocracy. Others, such as Jørgen Møller, have argued that electoral democracy is, if measured adequately, a better measure than illiberal democracy since truly competitive elections only take place in liberal democracies. Finally, it has also been contended that illiberal democracy is an unfortunate and potentially noxious misnomer since it offers the opportunity to populists and autocrats to promote illiberalism while preserving the veil of democracy.