Uganda: Managing Democracy through Institutionalised Uncertainty

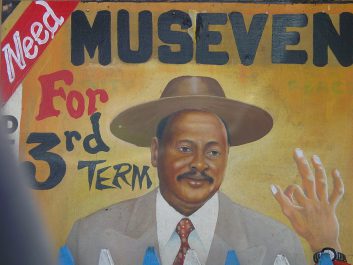

In 2016, thirty years after he violently seized power, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni was reelected to his fifth term in office. Museveni first took power in Uganda in 1986, after waging a five-year insurgency against the oppressive Obote regime. At that time, Uganda remained economically and socially devastated from years of autocratic rule, notably by the infamous dictator Idi Amin. Subsequent power struggles had further hollowed out the country’s governing institutions.

Democracy is not just the right to vote; it is the right to live in dignity.As president, Museveni made some early reforms. His implementation of decentralisation and structural adjustment policies attracted western support for a young regime. Uganda was swiftly labelled a “donor darling” on its way to democratic transition. However, in recent years, assessments of the regime have shifted. It is now seen as a hegemonic party-state that relies increasingly on patronage and violent coercion. Scholars have catalogued how decentralisation policies have actually recentralised state power and fragmented subnational power bases. The regime has used protracted civil conflict, including insurgencies across the country, to justify uneven development and a militarised state. Today, Uganda resembles other seemingly fragile African states with long-lasting regimes like Angola, Eritrea and Zimbabwe.

Such cases present a paradox. How can state fragility, a system of electoral governance, and autocratic rule coexist sustainably? An examination of how citizens experience Uganda’s illiberal regime is revealing. Unsurprisingly, the regime restricts civil liberties and maintains distributive systems that offer overwhelming structural advantage for the ruling regime. However, it also governs by instrumentalising uncertainty. This is achieved via arbitrary government use of authority, which is backed by a meaningful threat of violence. Government authorities retain discretion regarding whether they will respond to citizens’ claims, and if so, what rules they will apply. As a result, uncertainty infuses citizens’ perceptions of the state – particularly with respect to actions by state security actors but also those of politicians and state officials.

Crime preventers as electoral tools

Take the experience of Uganda’s “Crime Preventers”. So-called crime preventers are mainly underemployed young men, recruited en masse before the 2016 elections with promises of access to government loan schemes and employment in the police force. The mandate of these crime preventers was vaguely defined. Politicians on both sides of the aisle stoked fears that crime preventers would use violence to intimidate opposition voters and candidates, spy on opposition rallies and facilitate vote manipulation. However, the reality appears more mundane. At times, crime preventers were tasked with assisting the police in making arrests and detaining civilians. At other times, the police and centrally appointed officials asserted that these young men were ordinary community members, powerless except to report crime like any other citizen. Constant vacillations between promises made and broken, authority claimed and denied, contributed to a high level of uncertainty in interactions between citizens and crime preventers, and also between crime preventers and state authorities.

The government’s ability to continually redefine the role of crime preventers was made possible by a widely held perception that the ruling regime retained access to overwhelming and potentially violent force. As one municipal-level representative explained, “This government can liquidate you”. This perception is reinforced through citizens’ memories of state-sponsored violence. The ruling regime and its military have fought civil insurgencies since taking power, often sacrificing civilian life in the process. Sporadic and unpredictable state violence in everyday life further buttresses this perception. For example, the police often use teargas and live or rubber bullets to disperse rallies. More mundane instances of state coercion include security sweeps rife with intimidation and extortion.

institutionalised arbitrariness

The perception that the state could intervene anytime and deploy overwhelming force produces a particular type of subject, namely, one that is comparatively subdued and risk averse. Ordinary citizens self-police, giving wide berth to issues they imagine are sensitive.The perception that the state could intervene anytime and deploy overwhelming force to produce a subject that is comparatively subdued and risk averse. Pervasive uncertainty also erodes trust between constituents and authorities. Citizens are cognisant of the fact that politicians also face harsh sanctions for challenging the regime’s interests. Politicians who survive this system are thus assumed to be complicit in the regime, making citizens suspicious of those who claim to act in good faith. Unsubstantiated rumours further fuel this scepticism: tales of state-organised assassinations circulate when public figures die unexpectedly; allegations of bribery proliferate when politicians support the ruling party. However, producing suspicion without evidence allows politicians to maintain the possibility –however slight – that they could act in their constituents’ interests. In turn, this keeps many citizens marginally engaged with the democratic process.

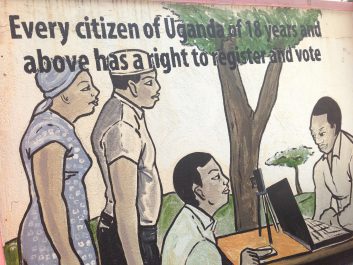

"Every citizen of Uganda has a right to register and vote" - wall mural at Electoral Commission

"Every citizen of Uganda has a right to register and vote" - wall mural at Electoral CommissionI have termed this strategy of rule “institutionalised arbitrariness”. Institutionalised arbitrariness helps explain how states maintain “hybridity” or “illiberal democracy” as the status quo. The arbitrary use of harsh discipline means that the state can permit occasional expressions of liberal politics such as democratic elections, universal suffrage, civil society, free association and a free press. It is thus difficult for citizens and international observers to decisively categorise the regime as oppressive and autocratic.

The functioning of a democracy is premised on the ability of citizens and their representatives to develop meaningful and reliable expectations of each other. Aspects of arbitrary governance – driven by rumours, fear and scepticism – have been observed in other countries. For example, Ricardo Soares de Oliveira describes state-making in the Angolan periphery, including attempts to foster the perception that the state could intervene to defend its interests anytime and anyplace, “crush[ing] its enemies” to produce “subjects rather than citizens”. David Bozzini describes how in Eritrea, harsh and uneven implementation of state laws against desertion from military service caused citizens to self-police in favour of the regime. Joost Fontein depicts Zimbabwean citizens self-policing in response to unpredictable state destruction of “illegal [housing] structures”.

The functioning of a democracy is premised on the ability of citizens and their representatives to develop meaningful and reliable expectations of each other. However, in environments marked by high uncertainty, arbitrary assertions and denials of state authority disrupt feedback loops and fragment citizen organisation. Under such circumstances, citizens in Uganda, Angola, or Eritrea cannot develop meaningful expectations, nor can they demand regime accountability. Thus, “illiberal democracies” can produce uncertainty and contingency to manipulate formally liberal governance for the pursuit of illiberal ends.

Longest-serving presidents in Africa

Definitions of Democracy

Democracy can be defined as, literally, the rule by the people. The term is derived from the Greek dēmokratiā, coined from dēmos (“people”) and kratos (“rule”) in the 5th century BCE. At heart, democracy is based on three principles: popular sovereignty, political participation and political contestation. Democracies may take on different constitutional forms (constitutional monarchy, republic) and modes of territorial organisation (unitary, federal).

The ballot box (free, fair and regular elections) defines democracy at its most basic. This minimalist or “thin” conception of democracy can be opposed to a more substantial or “thick” definition holding that in addition to elections, democracy needs to satisfy a series of further constitutional, liberal and/or social criteria.

In a direct democracy the people govern sovereignly by congregating in popular assemblies and taking decisions by popular vote (usually by show of hands, as in the Swiss cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus). There is no political representation. For thousands of years direct democracy remained the principal model of democracy as exerted in city-states or other small-scale polities.

Example: ancient Athens.

A representative or electoral democracy is a type of democracy where the people govern indirectly through elected representatives. It requires a set of political institutions different from those of direct democracy such as parliaments and regular elections. Representative democracy became prevalent in the 19th century with the emergence of large nation-states.

Liberal democracy is a subgenre of representative democracy defined not only by free and fair elections, but also by the rule of law, the separation of powers and the protection of basic civil liberties (freedom of speech, assembly and religion). Liberal democracies limit the exercise of executive power and majority rule through constitutions ensuring independent courts, the protection of minorities, and basic human rights.

Semidirect democracy is a mixed form of democracy where elected representatives govern and legislate but the citizens remain sovereign through referenda, initiatives and recalls. Even though today only Switzerland is a semi-direct democracy in the formal sense, many democracies have institutionalised elements of expression of popular will such as referenda.

Parliamentary democracy is a type of representative democracy where the executive branch of government depends on the support of the parliament, often expressed through a vote of confidence. The party that wins the largest number of congressional seats selects the prime minister, who controls the legislative process. The executive is divided into a head of government and a ceremonial head of state.

Examples: Australia, Germany, India, Spain.

Presidential democracy is a type of representative democracy where the executive branch is elected separately from the legislative branch. The parliament controls the budget, legislates, approves appointments to cabinet positions and ratifies foreign treaties. The president appoints cabinet members, commands the army and serves as the head of state and the head of government.

Examples: Argentina, Indonesia, United States, Venezuela.

Semi-presidential democracy is a type of representative democracy where a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet. It differs from the parliamentary system in that it has a popularly elected head of state, who is more than a purely ceremonial figurehead, and from the presidential system in that the cabinet, although named by the president, is responsible to the legislature, who can move a motion of no confidence.

Examples: France, Russia, Tunisia.

Participatory democracy refers to a regime where citizens participate actively in public decision-making. Instruments to broaden citizen participation include e-democracy and e-voting.

In a deliberative democracy authentic deliberation, not mere voting, is the primary source of a law’s legitimacy. Jürgen Habermas has made a fundamental contribution to deliberative democracy through his work on communicative rationality and the public sphere.

In a proportional system parties obtain seats proportionally to the votes they win. In a plurality system, candidates who win most votes in an electoral district are elected. In a majority system, candidates who win more votes than all others combined in an electoral district are elected. Proportional representation usually leads to a multiparty system whereas plurality and majority election favour bipartisanism.

United States

Russia

Uganda

Hungary

Turkey

Venezuela

This table shows the evolution of democracy in the USRussiaUgandaHungaryTurkeyVenezuela over 10 years. Arrows indicate the improvement (↗) or deterioration (↘) of a given indicator between 2006 and 2016. One arrow per 0.4 variance on a scale of 10.

| Aspects of democracy | Trend |

|---|---|

| Legislative constraints on the executive | ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘↘ ↗ |

| Judicial constraints on the executive | ↘ = ↗ ↘ ↘↘ ↘ |

| Government censorship (internet) | ↘↘ ↘ = ↗ ↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

| Government censorship (media) | ↘↘ ↗ = ↘↘ ↘↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

| Freedom of association | ↘ ↘ ↗ ↗ ↘ ↘ |

| Freedom house rule of law | ↘ = ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘ |

| Freedom of academic and cultural expression | ↘↘ ↘ ↘ ↘↘ ↘↘↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

Caricature de @Chappatte - www.chappatte.com Caricature de Beatriz Tirado

Source: Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit, EIU)

What Is Illiberal Democracy?

In his 1997 contribution to Foreign Affairs, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Fareed Zakaria defines illiberal democracies as “democratically elected regimes, often ones that have been reelected or reaffirmed through referenda, [but] are routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving their citizens of basic rights and freedoms”.

Fareed Zakaria is an Indian American journalist and author with a BA from Yale College and a PhD in Government from Harvard University. He worked as Adjunct Professor at Columbia University and as managing editor of Foreign Affairs from 1992 to 2000 (a post he was appointed to at only 28 years old). Zakaria has also been a columnist and editor for Newsweek, Time Magazine and The Atlantic. Currently he hosts Fareed Zakaria GPS – CNN’s flagship international affairs programme – and writes columns for The Washington Post. Foreign Policy named Zakaria one of its top 100 global thinkers. He is the author of five books, including The Future of Freedom (2003), The Post-American World (2008) and In Defense of a Liberal Education (2016).

- Consolidation of power in the executive

- Charismatic leader

- Erosion of the independence of the judiciary

- Weakening status of the parliament

- Recourse to direct democracy (plebiscites/referenda)

- Populist rhetoric/propaganda

- Discrimination of minorities

- Monitoring and moulding of civil society

- Media and internet censorship

- Curbs on academia and educational curricula

- Targeted repression of opponents

- Restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly

- Disregard for rule of law and human rights

- Misuse of state resources (cronyism)

- Emasculation of the electoral process

- Forging of external enemies

Illiberal democracy as a concept has been criticised for its diffuse meaning and close proximity to related, almost synonymous terms, such as: limited democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regimes, dysfunctional democracy, deconsolidating democracy, defective democracy and electoral authoritarianism. According to Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, the concept does not distinguish sharply enough democracies which have, in fact, never been truly democratic but claim to be so, from regimes that actually have successfully become or transitioned toward genuine democracy but are backsliding toward autocracy. Others, such as Jørgen Møller, have argued that electoral democracy is, if measured adequately, a better measure than illiberal democracy since truly competitive elections only take place in liberal democracies. Finally, it has also been contended that illiberal democracy is an unfortunate and potentially noxious misnomer since it offers the opportunity to populists and autocrats to promote illiberalism while preserving the veil of democracy.