The United States and the Trajectory of Democracy

In the wake of Trump’s election the United States’ traditional role as beacon of global democracy seems in jeopardy. The country’s long-standing democratic tradition and the capacity of its civil society to mobilise may, however, play a crucial role in counterbalancing the president’s illiberal agenda.

Perhaps the most worrisome dimension of the democratic recession has been the decline of democratic efficacy, energy, and self-confidence in the West, including the United States.

Almost 200 years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville published De la démocratie en Amérique, putting the intellectual seal of approval on the idea of US-style democracy as a model for other parts of the world. Tocqueville’s analysis went far beyond formal institutions and laws to the normative underpinnings of participation, equality, and voluntary association. Arguably, it is these norms which, in spite of the numerous evils in American history – from slavery and the destruction of the indigenous population to plutocracy, support for foreign dictators, and the tyranny of the majority mentioned by Tocqueville himself – served as a cynosure for people and countries around the world.

US democracy as a source of inspiration

10 décembre 2016.

The normative power of US democracy was that it was an ideal which, somehow, had been concretised. That this had occurred in the situation of what Louis Hartz called a “new society”, one without an hereditary aristocracy, with vast fertile lands only thinly settled by peoples who could easily be swept aside, and with oceans and distracted great powers protecting it from invasion, was mostly elided by those who drew inspiration from the democratic norms they saw flourishing in the United States. Indeed, even the most scathing political critics of the US found themselves having at least to quote, perhaps to finesse, or, horrors, to adopt outright, features of what they imagined to be American democracy. From attempts at extending the franchise through to legislation modeled on the Freedom of Information Act, US democratic norms continued to serve as a model.

At first, this influence stemmed from the obvious contrast between the US experience and that of Europe. In the 20th century, other factors were added: economic and military power, language, universities, popular culture, and the sheer omnipresence of the mass media. These in turn led to a sort of path dependence, in which elites in other countries acquired the habit of looking to the United States for ideas about participation and transparency, not to mention the details of certain types of legislation, administrative arrangements within organisations, the setting up of advisory bodies, and, of course, many other facets of US society unrelated to democratic norms. The fact that many of those elites in other countries had themselves been educated in the United States, understood English, and had grown up consuming US popular culture, further reinforced this habit. Thus, even if many US political ideas, such as its 18th-century constitution or its insistence on first-past-the-post voting rules, were no longer imitated, the habit of looking to the United States, perhaps copying certain of its practices, but in any case using those practices as an argument for certain policies, remained alive and well. Not even the presidency of George W. Bush, with its hanging chads, invasion of Iraq, and heartbreaking incompetence on Hurricane Katrina, could stamp out that habit: numerous US expatriates can attest to being congratulated by complete strangers after the election of Barack Obama in 2009.

THE INternational impact of trump’s illiberal agenda

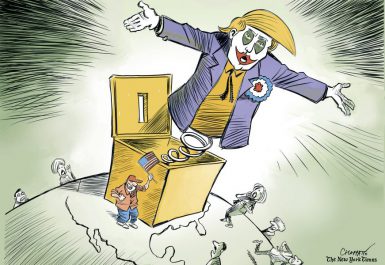

One would like to imagine that this changed after Trump assumed the presidency in 2017. To some degree it did, as elites lowered their expectations for US policy and focused instead on short-term coordination with their American counterparts. But this is to ignore the enormous boost that Trump’s talking points, and the aides he appointed, gave to xenophobic and authoritarian forces around the world. It is no accident that European advocates of immigration restrictions and crackdowns on the press, the judiciary, and dissenting voices lauded Trump, even before election night; by the same token, there is clear mutual admiration between Trump and various autocratic leaders. In effect, the United States is still a model, albeit an antidemocratic one.

This, however, is not the end of the story, or even of the current episode. We would do well to recall that the United States was a democratic inspiration not only, or even primarily, because of its constitution, its relatively broad electorate, its legislative arrangements, or its free press, but also because of its protest movements.The United States was a democratic inspiration not only because of its constitution, its relatively broad electorate, its legislative arrangements, or its free press, but also because of its protest movements. The story of Gandhi being inspired by Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience is well-known, but this is only the tip of the American iceberg. For example, trade union struggles (which resulted, among other things, in the choice of 1 May as International Workers’ Day), antiwar protests, and the multiple strands of protests for civil rights (most famously the Civil Rights Movement against racial injustices) each had a marked influence on analogous activities in numerous countries. The point is not that protest movements in the United States served as models elsewhere: some did, but in other cases, influence ran in the other direction. Rather, the fact that protests did occur in the United States, in the face of well-known antidemocratic barriers, was itself significant to activists in other countries. As one South African campaigner put it, “When the sit-ins started in the USA, I felt I was there. We read the news eagerly and identified unconditionally with those who were demanding their basic rights.”

Thus, the jury is still out on whether or not the United States, under Trump, will become an antidemocratic model. In the end, what matters is not so much what Trump does as what his fellow citizens do in response.

Changes in Democratic Attitudes in the United States (ages 18–25)

Source: AmericasBarometer by LAPOP.

Definitions of Democracy

Democracy can be defined as, literally, the rule by the people. The term is derived from the Greek dēmokratiā, coined from dēmos (“people”) and kratos (“rule”) in the 5th century BCE. At heart, democracy is based on three principles: popular sovereignty, political participation and political contestation. Democracies may take on different constitutional forms (constitutional monarchy, republic) and modes of territorial organisation (unitary, federal).

The ballot box (free, fair and regular elections) defines democracy at its most basic. This minimalist or “thin” conception of democracy can be opposed to a more substantial or “thick” definition holding that in addition to elections, democracy needs to satisfy a series of further constitutional, liberal and/or social criteria.

In a direct democracy the people govern sovereignly by congregating in popular assemblies and taking decisions by popular vote (usually by show of hands, as in the Swiss cantons of Appenzell Innerrhoden and Glarus). There is no political representation. For thousands of years direct democracy remained the principal model of democracy as exerted in city-states or other small-scale polities.

Example: ancient Athens.

A representative or electoral democracy is a type of democracy where the people govern indirectly through elected representatives. It requires a set of political institutions different from those of direct democracy such as parliaments and regular elections. Representative democracy became prevalent in the 19th century with the emergence of large nation-states.

Liberal democracy is a subgenre of representative democracy defined not only by free and fair elections, but also by the rule of law, the separation of powers and the protection of basic civil liberties (freedom of speech, assembly and religion). Liberal democracies limit the exercise of executive power and majority rule through constitutions ensuring independent courts, the protection of minorities, and basic human rights.

Semidirect democracy is a mixed form of democracy where elected representatives govern and legislate but the citizens remain sovereign through referenda, initiatives and recalls. Even though today only Switzerland is a semi-direct democracy in the formal sense, many democracies have institutionalised elements of expression of popular will such as referenda.

Parliamentary democracy is a type of representative democracy where the executive branch of government depends on the support of the parliament, often expressed through a vote of confidence. The party that wins the largest number of congressional seats selects the prime minister, who controls the legislative process. The executive is divided into a head of government and a ceremonial head of state.

Examples: Australia, Germany, India, Spain.

Presidential democracy is a type of representative democracy where the executive branch is elected separately from the legislative branch. The parliament controls the budget, legislates, approves appointments to cabinet positions and ratifies foreign treaties. The president appoints cabinet members, commands the army and serves as the head of state and the head of government.

Examples: Argentina, Indonesia, United States, Venezuela.

Semi-presidential democracy is a type of representative democracy where a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet. It differs from the parliamentary system in that it has a popularly elected head of state, who is more than a purely ceremonial figurehead, and from the presidential system in that the cabinet, although named by the president, is responsible to the legislature, who can move a motion of no confidence.

Examples: France, Russia, Tunisia.

Participatory democracy refers to a regime where citizens participate actively in public decision-making. Instruments to broaden citizen participation include e-democracy and e-voting.

In a deliberative democracy authentic deliberation, not mere voting, is the primary source of a law’s legitimacy. Jürgen Habermas has made a fundamental contribution to deliberative democracy through his work on communicative rationality and the public sphere.

In a proportional system parties obtain seats proportionally to the votes they win. In a plurality system, candidates who win most votes in an electoral district are elected. In a majority system, candidates who win more votes than all others combined in an electoral district are elected. Proportional representation usually leads to a multiparty system whereas plurality and majority election favour bipartisanism.

United States

Russia

Uganda

Hungary

Turkey

Venezuela

This table shows the evolution of democracy in the USRussiaUgandaHungaryTurkeyVenezuela over 10 years. Arrows indicate the improvement (↗) or deterioration (↘) of a given indicator between 2006 and 2016. One arrow per 0.4 variance on a scale of 10.

| Aspects of democracy | Trend |

|---|---|

| Legislative constraints on the executive | ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘↘ ↗ |

| Judicial constraints on the executive | ↘ = ↗ ↘ ↘↘ ↘ |

| Government censorship (internet) | ↘↘ ↘ = ↗ ↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

| Government censorship (media) | ↘↘ ↗ = ↘↘ ↘↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

| Freedom of association | ↘ ↘ ↗ ↗ ↘ ↘ |

| Freedom house rule of law | ↘ = ↘ ↘ ↘ ↘ |

| Freedom of academic and cultural expression | ↘↘ ↘ ↘ ↘↘ ↘↘↘↘↘↘ ↘↘ |

Caricature de @Chappatte - www.chappatte.com Caricature de Beatriz Tirado

Source: Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit, EIU)

What Is Illiberal Democracy?

In his 1997 contribution to Foreign Affairs, “The Rise of Illiberal Democracy”, Fareed Zakaria defines illiberal democracies as “democratically elected regimes, often ones that have been reelected or reaffirmed through referenda, [but] are routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving their citizens of basic rights and freedoms”.

Fareed Zakaria is an Indian American journalist and author with a BA from Yale College and a PhD in Government from Harvard University. He worked as Adjunct Professor at Columbia University and as managing editor of Foreign Affairs from 1992 to 2000 (a post he was appointed to at only 28 years old). Zakaria has also been a columnist and editor for Newsweek, Time Magazine and The Atlantic. Currently he hosts Fareed Zakaria GPS – CNN’s flagship international affairs programme – and writes columns for The Washington Post. Foreign Policy named Zakaria one of its top 100 global thinkers. He is the author of five books, including The Future of Freedom (2003), The Post-American World (2008) and In Defense of a Liberal Education (2016).

- Consolidation of power in the executive

- Charismatic leader

- Erosion of the independence of the judiciary

- Weakening status of the parliament

- Recourse to direct democracy (plebiscites/referenda)

- Populist rhetoric/propaganda

- Discrimination of minorities

- Monitoring and moulding of civil society

- Media and internet censorship

- Curbs on academia and educational curricula

- Targeted repression of opponents

- Restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly

- Disregard for rule of law and human rights

- Misuse of state resources (cronyism)

- Emasculation of the electoral process

- Forging of external enemies

Illiberal democracy as a concept has been criticised for its diffuse meaning and close proximity to related, almost synonymous terms, such as: limited democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regimes, dysfunctional democracy, deconsolidating democracy, defective democracy and electoral authoritarianism. According to Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, the concept does not distinguish sharply enough democracies which have, in fact, never been truly democratic but claim to be so, from regimes that actually have successfully become or transitioned toward genuine democracy but are backsliding toward autocracy. Others, such as Jørgen Møller, have argued that electoral democracy is, if measured adequately, a better measure than illiberal democracy since truly competitive elections only take place in liberal democracies. Finally, it has also been contended that illiberal democracy is an unfortunate and potentially noxious misnomer since it offers the opportunity to populists and autocrats to promote illiberalism while preserving the veil of democracy.