Flowing with Data: Digital Humanitarianism Today

The production, dissemination and analysis of data has entered a new stage, as reflected in the sheer expansion of data-hungry tools. The notions of data flows and data “management” have become pervasive to all forms of governance and professional environments – both public and private. The pace of data production currently by far surpasses joint capacity for analysis and subverts conventional decision-making processes.

To understand the wide impact of data flows it might be useful to take a specific example – in this case, the role of data in humanitarian response and disaster relief. It is increasingly accepted that information management is critical to the future of international and humanitarian action. In many ways data has become increasingly important to the way we think and talk about conflicts and humanitarian responses. At the international level, the prioritisation of data is clear in the report of the UN High-Level Panel on the Post-2015 Development Agenda’s call for a “data revolution” which “would draw on existing and new sources of data to fully integrate statistics into decision making [and] promote open access to, and use of, data” (2013, 24). In his report for the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in 2016, Ban Ki-moon expressed the view that data might help prevent some of the most egregious violations of international humanitarian law or contribute to alleviate their effects: “The systematic collection and reporting of data on violations will help to enhance the delivery and safety of humanitarian and medical assistance” (2016, 16). The same document also envisions the collection of data as a tool for effective international accountability: “The universality of the 2030 Agenda makes it imperative that every country commit to collecting comprehensive data and analysis to better identify, prioritize and track the progress of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups towards the Sustainable Development Goals” (22).

Planification may become superior to the market economy and dictatorships superior to democracies. Those able to control data will be able to predict and satisfy individual needs.While investing much hope and credit in the transformative power of data per se, Ban Ki-moon and most of the international humanitarian community agreed that for data and joint analysis to “become the bedrock of our action” (Ban Ki-moon 2016, 31) much needed to be invested to make sense of past events and modelling future ones.

Vacillating between frantic enthusiasm and anxiety over the noxious potential of ill-channelled data flows, the World Humanitarian Summit represented an initial step in the political harnessing of a transformative agenda arising, as if technologically determined, from the bountiful mass of evidence begging to be analysed. As Stuart Garman noted, “the pervasive attitude is one of optimism, bordering on technological determinism, which champions the transformative potential of communications technology; assumes the synonymy of innovation and increased effectiveness; and urges organizations and aid workers to get on board, or get left behind” (2015, 440). Yet, data is not knowledge, nor is it capacity to analyse it Yet, data is not knowledge, nor is it capacity to analyse it. Many of the developments in digital humanitarianism seem to be driven by what is possible rather than what is needed, to the extent that, as Trevor Barnes noted with regards to the data revolution in geography, “computational techniques and the avalanche of numbers become ends in themselves, disconnected from what is important” (2013, 299). He poses an important question: are we generating useful knowledge or are we collecting “data for data’s sake” (ibid.)? Much could be said of the distance between “inactionable” and “actionable data” (Mancini and O’Reilly 2013, 3) that decision makers and humanitarian workers require. In practice, even though the volume of data grows exponentially, it is often “inactionable” data that is produced.

Information systems are political ecologies that are shaped by power, inequality and change. Unlike alternative political ecologies, the gatekeeping of data flows and the algorithms generating them is more difficult to harness and largely eludes the commonly available tools for political analysis. Being in its infancy, many outcomes of this technological turn remain unforeseen just as underlying ethical and political issues will only become prevalent and obvious in hindsight. Taking heed of Barnes’ challenge that “big data comes with big history” (2013, 298), we ought to seek a finer understanding of the politics of control and counterpower that are implicit in this revolutionary turn. We need social sciences to devote more space and critical analysis to the politics and history of data technologies. Many relevant disciplines are currently siloed – they need to become more widely shared. The pace of data production compares unfavourably with the resources devoted to make sense of it except in the most self-reinforcing fashion. Technologies have irrupted in the past but seldom have they been challenging the analytical capacity of the concerned actors so thoroughly.

In the sense that data represents a new form of globalised world order, the main challenges it presents are associated with old debates on sovereignty, control and political responsibility. Where these recent changes are blatantly most challenging is in their potential for mystification and disordered proliferation. To take control and to make data uses accountable and responsible requires investment and mental retooling.

What is Globalisation?

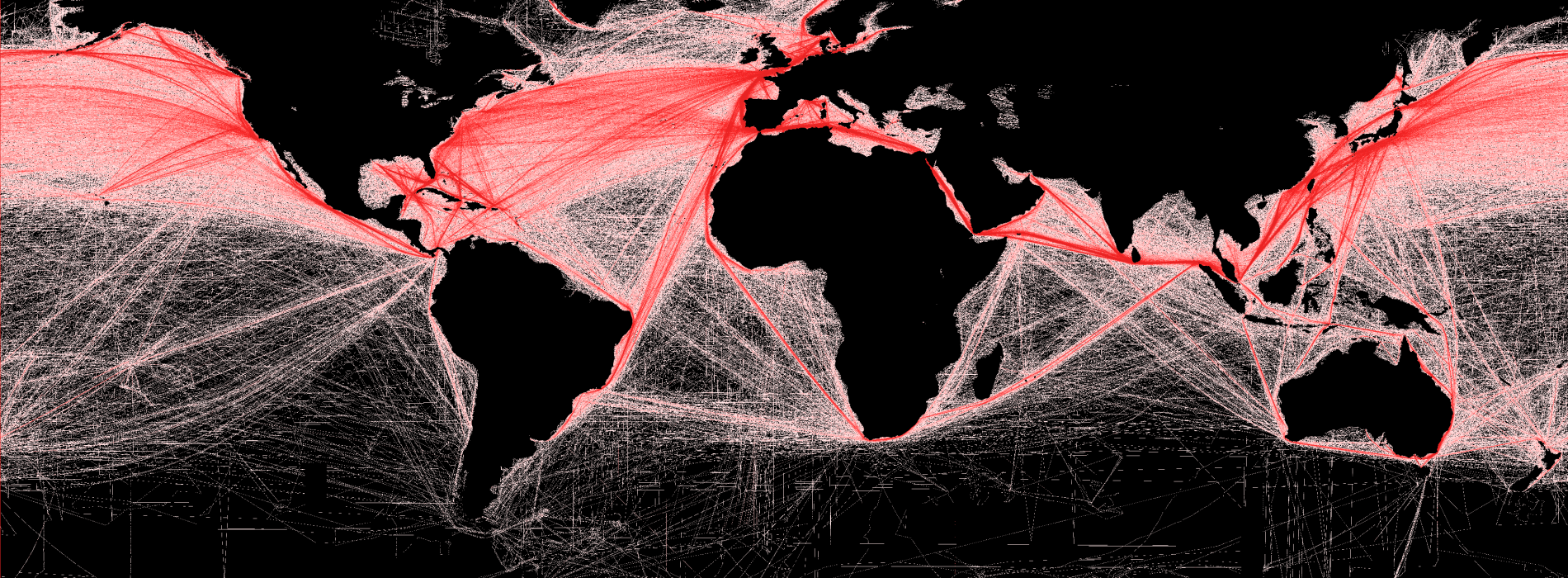

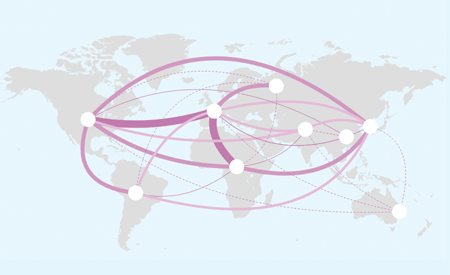

Australia (2007–2010), as "the contraction of time and space in international transactions through the platform of new technologies". Globalization depends on (infra-)structure (roads, trains, shipping, flight routes, cables, ports), geo-climatic factors (global warming), technological innovations (digitalization; green energy, logistics, ITC) and, last but not least, a framework transnational norms. It rests on the twin logic of the acceleration and increase of the volume of exchanges of goods, capital, services, people and ideas, as well as the steady densification of geographic connectedness.

The IMF identifies four basic aspects of globalization: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and movement of people and the dissemination of knowledge. Further, environmental challenges such as climate change, cross-boundary water, air pollution, and over-fishing of the ocean are linked with globalization. Globalizing processes affect and are affected by business and work organization, economics, socio-cultural resources, and the natural environment.

Proponents of globalization argue that it allows poor countries and their citizens to develop economically and raise their standards of living, while opponents of globalization claim that the creation of an unfettered international free market has benefited multinational corporations in the Western world at the expense of local enterprises, local cultures, and common people. Resistance to globalization has therefore taken shape both at a popular and at a governmental level as people and governments try to manage the flow of capital, labor, goods, and ideas that constitute the current wave of globalization.

The Expanding Network of Global Flows

Source: McKinsey Global Institute