International Migration: A Canary in the Coalmine of Globalisation

International migration is inextricably linked with globalisation. On one hand, processes of globalisation drive international migration, including through disparities in development, demography and democracy; the global jobs crisis; the segmentation of global labour markets; revolutions in communications and transportation; and transnational social networks. On the other hand, international migration itself generates processes of globalisation, including the global transfer of money and goods; the emergence of global cities; and growing social and cultural diversity.

In comparison with trade and capital, however, the global movement of labour remains restricted. This is because international migration strikes at the heart of issues that are paramount to sovereignty, including national identity, economic competitiveness, and security. Hence the paradox that while most industrialised countries require more migrants to fill labour market gaps and address demographic trends, most are nevertheless restricting migration in response to political and populist pressures.

In comparison with trade and capital, however, the global movement of labour remains restricted In this way, international migration can be considered a canary in the coalmine of globalisation: it will either flourish as the forces of globalisation overcome nationalism, or its reduction may be an indication that globalisation has peaked and is retreating.

According to United Nations data, in 2015 244 million people had lived outside their country for more than one year (a figure that excludes people who move for shorter periods, for example as students, tourists or seasonal workers, and, of course, the many more who move inside their own country). This total includes about 20 million refugees – on one hand an historical high of people forced from their countries, on the other still a relatively small proportion of the totality of migration.

Canary in a Coal mine… wear a mask!

Canary in a Coal mine… wear a mask!International migrants comprised about 2.8% of the world’s population in 2000, and 3.3% of a significantly larger world population by 2015. Most projections suggest that the proportion of migrants in a continually expanding world population will continue to grow over the next century, in particular as a result of steepening demographic gradients, and the effects of climate change. The Fourth Industrial Revolution is likely to further boost and complexify international migration, notably by altering the ratios between irregular to regular and unskilled to high-skilled migrants as well as improving the gender balance.

However, while such indicators suggest that international migration will likely continue to expand, they may not necessarily indicate the amplification of globalisation. First, international migration is not really global international migration is not really global. While about 10% of the population in Europe, North America and Oceania are international migrants, only about 2% are so in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Most migrants move within their own region. Second, it is likely that a growing proportion of international migrants may be moving without authorisation, responding to global pull and push factors but in increasing contravention of national laws, policies and interests. Third, in many countries international migration is increasingly (and usually inaccurately) viewed as a threat, fuelling anti-globalisation sentiments.

There is one final arena where international migration has an uneasy relationship with globalisation, and that is global governance. Until the International Organization for Migration (IOM) became an associated agency of the UN in 2016, it had often been pointed out that international migration was one of the few truly global issues without a dedicated UN agency. Even now the integration of IOM in the UN system remains contested. It is still true that there is no single legal or normative framework that applies to all migrants – the rights of irregular migrants remain especially contested.

At the same time, the international community has rallied behind a new Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, the zero draft of which has recently been published, and which will now be negotiated by states before its launch at the end of 2018. While the draft does not make bold propositions on global governance, it does identify a series of guiding principles – including the potential contradiction between “international cooperation” and “national sovereignty” – and 22 objectives – including the ambition to minimise the structural factors that compel people to leave their country of origin – that may promote more coherence in international responses to migration.

International migration is just one indicator for the future of globalisation, albeit an important one. Projections for the future of migration perhaps indicate a new era of reluctant globalisation. The global forces that drive migration will expand, but there will be increasing efforts to harness its patterns and outcomes. The canary will live, but may not sing.

The future treaty on the free movement of persons in Africa

The Graduate Institute Geneva

What is Globalisation?

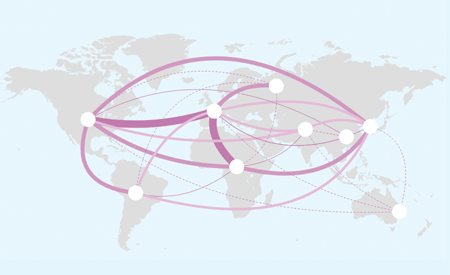

Australia (2007–2010), as “the contraction of time and space in international transactions through the platform of new technologies”. Globalization depends on (infra-)structure (roads, trains, shipping, flight routes, cables, ports), geo-climatic factors (global warming), technological innovations (digitalization; green energy, logistics, ITC) and, last but not least, a framework transnational norms. It rests on the twin logic of the acceleration and increase of the volume of exchanges of goods, capital, services, people and ideas, as well as the steady densification of geographic connectedness.

The IMF identifies four basic aspects of globalization: trade and transactions, capital and investment movements, migration and movement of people and the dissemination of knowledge. Further, environmental challenges such as climate change, cross-boundary water, air pollution, and over-fishing of the ocean are linked with globalization. Globalizing processes affect and are affected by business and work organization, economics, socio-cultural resources, and the natural environment.

Proponents of globalization argue that it allows poor countries and their citizens to develop economically and raise their standards of living, while opponents of globalization claim that the creation of an unfettered international free market has benefited multinational corporations in the Western world at the expense of local enterprises, local cultures, and common people. Resistance to globalization has therefore taken shape both at a popular and at a governmental level as people and governments try to manage the flow of capital, labor, goods, and ideas that constitute the current wave of globalization.

The Expanding Network of Global Flows

Source: McKinsey Global Institute