Darkness at Noon: Deforestation in the new Authoritarian Era

The dramatic Amazon fires images of August 2019 triggered a geopolitical outcry. Brazilian President Bolsonaro, however, unflinchingly continues to support his destructive model of Amazonian development. This article recalls the extent of the disaster and delves into the reasons behind such disdain for environmental concerns.

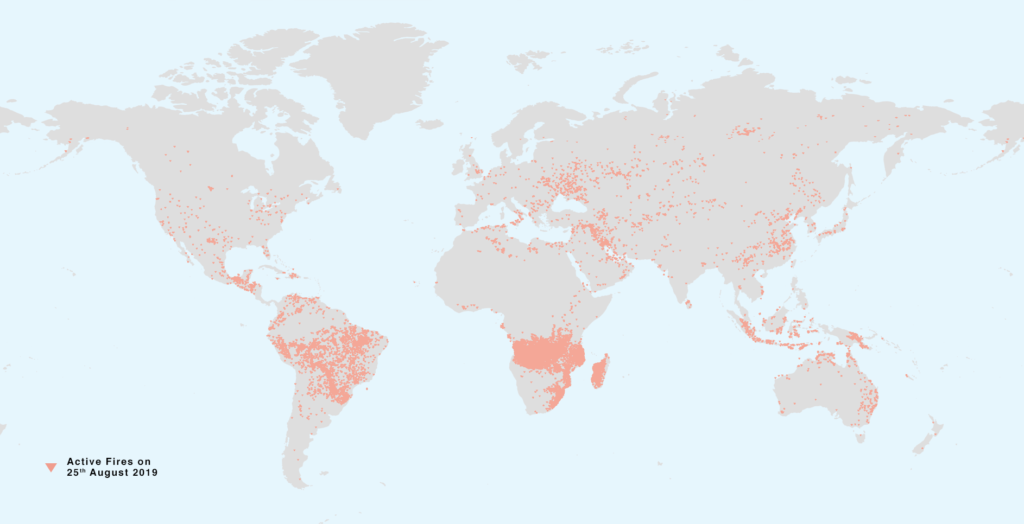

It is pretty hard to know many hectares of Amazonian forests you had to burn to shroud this hemisphere’s largest megacity, São Paulo, about 2,500 km from the Amazon, in enough smoke to completely darken its skies. But we do have some numbers on fires in Brazil (over 85,000) and Amazonia (close to 44,000). The area that burned all over Amazonia since the beginning of the year nudges up to over 1.9 million ha (Brazil) and another million in Bolivia, and it’s not done yet though heavy rains slowed the fires in Bolivia. We know that the number of fires was up 88% from the previous year thanks to Brazil’s world-class remote sensing Institute for Spatial Research (INPE) whose physicist director, Dr Ricardo Galvão, was fired for reporting this to Brazil’s right-wing president, Jair Bolsonaro. It’s a good thing that beheadings are now frowned upon, because Dr Galvão would certainly have lost his. Other major South American cities such as Santa Cruz, Bolivia, and the large soybean entrepot of Porto Velho were also wheezing through darkness at noon with the unbreathable air, the explosion in hospital visits and newly asthmatic, choking children. This will be more or less the state of things until the heavier rains come at the end of the year.

Immolated ecosystems

The dramatic Amazon fires images were coming in a year of the hottest summer ever recorded, when Paris vied with Death Valley for the hottest spot on the planet for a few days (44°C), Fairbanks, Alaska, basked in 32°C heat, and Siberian fires blazed in the Arctic while glaciers simply dissolved at unprecedented rates. The scorching heat continued in October 2019, also the hottest month on record. The images of the vast burnings – a human arson on a more or less unthinkable scale – were dramatically visible from space, from drones and from distressing ground photos which made the heat feel palpable, the apocalypse now. Forest fire smoke, CO2 and the DNA of the most complex systems on the planet became mere ash, a new kind of urban pollution. The immolated ecosystems swirled into the atmosphere to further bake more greenhouse gases into the sky, reducing its plants and animals to their constituent chemicals in the claggy dust and the charred remains of a world perhaps now gone forever.

The Presidential Response

The ghastly images soon triggered a geopolitical outcry. Jair Bolsonaro and his minister for the exterior, Ernesto Araújo, are both climate “sceptics” while his environmental minister, Roberto Salles, widely despised by Brazil’s environmental community, views climate as a “secondary issue”. US President Donald Trump, his Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and many of his other appointees are also climate change deniers whose policies can be summed up in the US withdrawal from the Paris climate accord. They all suddenly found that at the G7 meeting in France, Amazon burning and its climate implications had leapt, irritatingly, into an agenda item. Bolsonaro vaulted into action with his usual rebarbative comments. First, he refused the monies offered by the European Union (22 million euros – actually a risible sum given the scale of the burning) because he felt that French President Emmanuel Macron had insulted him. Bolsonaro was, however, willing to take funds from Boris Johnson’s United Kingdom, and happy to send in 44,000 troops in a symbolic display of his Amazonian affection and military bona fides. Mr Trump struck a special note of solidarity by opening up US rainforest, the Tongass forest of Alaska, to unregulated cutting. A bit later, Araujo and Pompeo agreed on a 100-million-dollar deal to “protect biodiversity” by the private sector and to create business opportunities in the most remote and inaccessible areas of Amazonia, for which read mining and timber plunder in protected areas and indigenous reserves.

The Bolsonaro faction began almost at once a “blame” campaign. The playbook deployed some of the usual tropes. Bolsonaro reproached the international press for the reputational hit on Brazil’s global standing following biased reporting that misrepresented the process of deforestation as destruction rather than the gloss of Brazilian development. Next, with laser-like focus, many varieties of international conspiracy were invoked. There were the subversive international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) who were setting the fires and then filming the ensuing holocaust in order to make the Bolsonaro regime look bad. Environmental NGOs, especially Greenpeace and World Wildlife Fund, were targeted as villains and could very soon be banned from Brazil. Other environmental and indigenous NGOs that received funding from government agencies saw their budgets evaporate.

Brazil’s agroelites have been perfectly willing to burn up more than 40,000 species of plants to make a habitat for just one – soy. “Amazonia is ours”, bellowed Bolsonaro while articulating a view popular in military circles that environmentalists use indigenous people as stooges to threaten Brazilian sovereignty and the Christian Brazilian way of life by asserting indigenous autonomy. “They [Indians] don’t have lobbyists and don’t even speak Portuguese. How is it that indigenous people have ended up with so much of our land?”, he asked (see this article in Campo Grande News). The idea is that with autonomy, which is inscribed in the 1988 constitution, these native “nations” could become platforms for a kind of internal invasion, a sort of ecofoco to update the revolutionary terminology of Che Guevara.

This was the starting point for several other rants by Bolsonaro and his allies, about how inhibiting Amazonian deforestation masked a panoply of more sinister geopolitical strategies, including a desire to limit the import of cheap Brazilian agricultural goods into Europe by backing out of the free trade agreement MERCOSUR on specious environmental grounds. In a more ominous register (and a zombie nostrum revived from the earlier military time), inhibiting deforestation was meant to forever condemn Brazil to underdevelopment by thwarting its agroindustrial ranchers and soy farmers from taking their rightful position as Amazonian territorial masters.

The reasons behind the disdain for environmental concerns

High resolution satellite image of slash-and-burn fires and smoke clouds in the Amazon rain forest in August 2019, Amazon basin, Mato Grosso, Brazil, contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data [2019]

High resolution satellite image of slash-and-burn fires and smoke clouds in the Amazon rain forest in August 2019, Amazon basin, Mato Grosso, Brazil, contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data [2019]But what was, in fact, triggering deforestation? During his election campaign, Bolsonaro advocated amnesty for deforesters and timber thieves, and this is a promise he has kept. He vowed to open up indigenous and traditional peoples’ lands to mining and to curtail their rights over the land. He vowed that not one more centimetre of indigenous lands or Kilombo (runaway slave communities) territories would be demarcated or legalised, and so far that is the case.

Bolsonaro would also shut down Brazil’s environmental ministry, relax environmental law enforcement and licensing, and back out of the Paris climate accord. He has not been able to do exactly that, but his environmental minister, Ricardo Salles, shortly after taking the reins, attacked the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural resources (IBAMA). He dismissed 27 of its 29 regional agency heads, replacing them with military men, slashed its budget by more than 24% and fired many of its field people. Even as IBAMA′s trucks and office were going up in flames, and their ability to carry out any enforcement was made impossible through Salles′s draconian cuts, Bolsanaro continued to derogate and insult the institution and its workers.

As an expression of further pique and disdain for environmental advocacy, responsibility, and Brazil’s scientific community, Bolsonaro completely defunded the Brazilian equivalent of the Swiss National Science Foundation. Although the scholarship funds were reinstated in early November after massive international and national pressure, Brazil’s world-class universities and laboratories, not to mention its distinguished scientists and its research across multiple disciplines, faced a precarious future. Accustomed to a science-inflected development policy for Amazonia – indeed that has been its hallmark for the last 30 years – its academic analysts found themselves largely shut out of decisions, and the few meetings they attended crammed with obedient military men. Meanwhile, the new military coterie inhabiting the climate negotiations staff had to be informed that Brazil was due to host a climate summit, COP25. Brazil later cancelled this commitment, and COP 25 will unfold in Madrid. This episode was emblematic of the degree of cluelessness among the inheritors of what had been one of the jewels in the crown of Brazilian diplomacy – and of the indifference to the climate process itself.

WhatBolsonaro has de facto decriminalised land grabbing on an unprecedented level. is the meaning or value of stewardship if you believe in the end times, as do Brazil’s Evangelical influencers (Bolsonaro is one), who have risen to the top policy strata? The general slogan that integrates the president’s constituents, “Bibles, beef and bullets”, more or less sums up his coalitions: fundamentalist Christians, agroindustry and the military. Bolsonaro has de facto decriminalised land grabbing on an unprecedented level, encouraging clearing as a means of claiming – the tried and true method of land capture by fraud and force. After valuable timber is hauled out, there are enormous speculative gains to be made by selling land. The famously unproductive cattle system, which is now applied in about 80% of Amazon cleared areas, serves more as a means of “place holding” in the creation of an asset by privatising public resources, taking advantage of the initial nutrient flush in the ashes of the burnt forests, and then selling out. Laundering money gained from illegal gold, timber and drugs also features in this process.

The clearing process is attended by a great deal of violence, because these forests are inhabited. Amazonian deforestation in many areas has been outsourced to “forest mafias” – an innovation in the agroindustrial complex. In a manner similar to farm management services, landowners can contract these mafias for “social cleansing” (limpieza is the Portuguese word for running out local farmers and natives off the land), haul out the timber, cut and burn what remains. The rather old-fashioned means of simply hiring a gunman is still popular, but the new system is a more “full-service” one in that the entire transformation of the land from expulsion to deforestation and then geolocating the new area on the rural land cadastre (CAR) – which does not confer title, but confusingly seems to – comprises this innovation in “one-stop shopping”.

Indeed, Brazil’s agroelites have been perfectly willing to burn up more than 40,000 species of plants to make a habitat for just one – soy – and to immolate a world of more than 100,000 different kinds of animals (an underestimate) to make space for only another species – the cow. This would move our world from the Anthropocene – the age of Man – to what biologist E. O. Wilson has called the Eremocene – the Age of Loneliness – as we preside over the sixth biodiversity extinction and a loss of more than a million species.

The old aphorism has it that we will see the end of the world before we will see the end of capitalism. What we are certainly seeing in Amazonia is what is called locally “capitalism selvagem” (“untamed” or “jungle capitalism“), and for many, their worlds have already gone, the epitaph written in smoke.

Land degradation | Key terms

Like many common words, the word soil has several meanings. In its traditional meaning, soil is the natural medium for the growth of plants. Soil has also been defined as a natural body consisting of layers (soil horizons) that are composed of weathered mineral materials, organic material, air and water. Soil is the end product of the combined influence of climate, topography and organisms (flora, fauna and human) on parent materials (original rocks and minerals) over time. As a result, soil differs from its parent material in texture, structure, consistency, color, chemical, biological and physical characteristics. Soil is an essential component of land and eco-systems, which both are broader concepts encompassing vegetation, water and climate in the case of land, and in addition to those three aspects, also social and economic considerations in the case of ecosystems.

The word soil is also known as dirt, waste or earth.

Soil erosion is a common term that is often confused with soil degradation as a whole, but in fact refers only to absolute soil losses in terms of topsoil and nutrients. This is indeed the most visible effect of soil degradation, but it does not cover all of its aspects. Soil erosion is a natural process in mountainous areas, but is often made much worse by poor management practices.

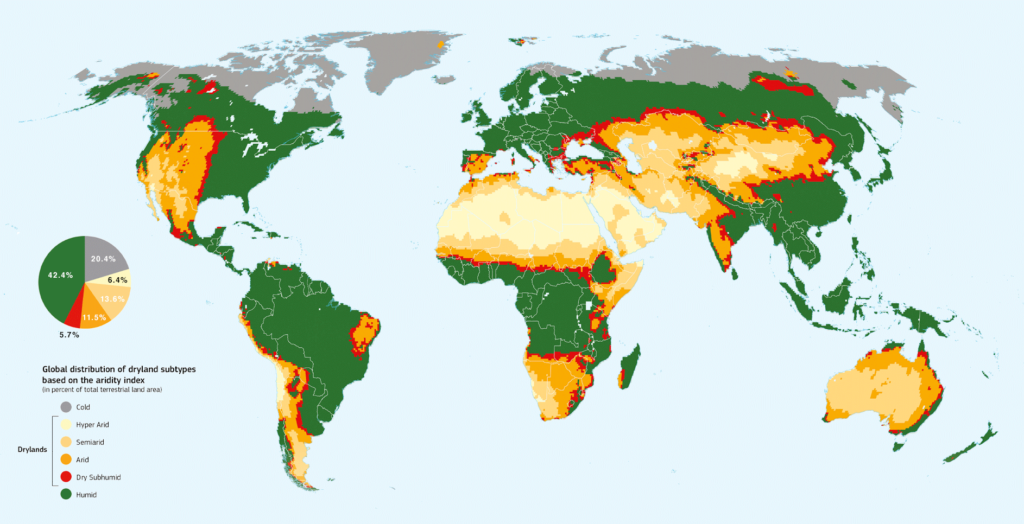

Land degradation has a wider scope than both soil erosion and soil degradation in that it covers all negative changes in the capacity of the ecosystem to provide goods and services (including biological and water-related goods and services, and, in the vision of LADA – Land Degradation Assessment in Dryland – also land-related social and economic goods and services).

Desertification is another common term used for (a) land degradation in dryland areas and/or (b) the irreversible change of the land to such a state it can no longer be recovered for its original use.

Mitigation is intervention intended to reduce ongoing degradation. This comes in at a stage when degradation has already begun. The main aim is to halt further degradation and to start improving resources and their functions. Mitigation impacts tend to be noticeable in the short-to-medium term: this then provides a strong incentive for further efforts. The word mitigation is also sometimes used to describe the reductions of impacts of degradation.

Rehabilitation is required when the land is already degraded to such an extent that the original use is no longer possible and the land has become practically unproductive. Longer-term and often more costly investments are needed to show any impact.

Land degradation neutrality describes the state whereby the amount and quality of land resources, necessary to support ecosystem functions and services and enhance food security, remains stable or increases within specified temporal and spatial scales and ecosystems (source: UNCDD).

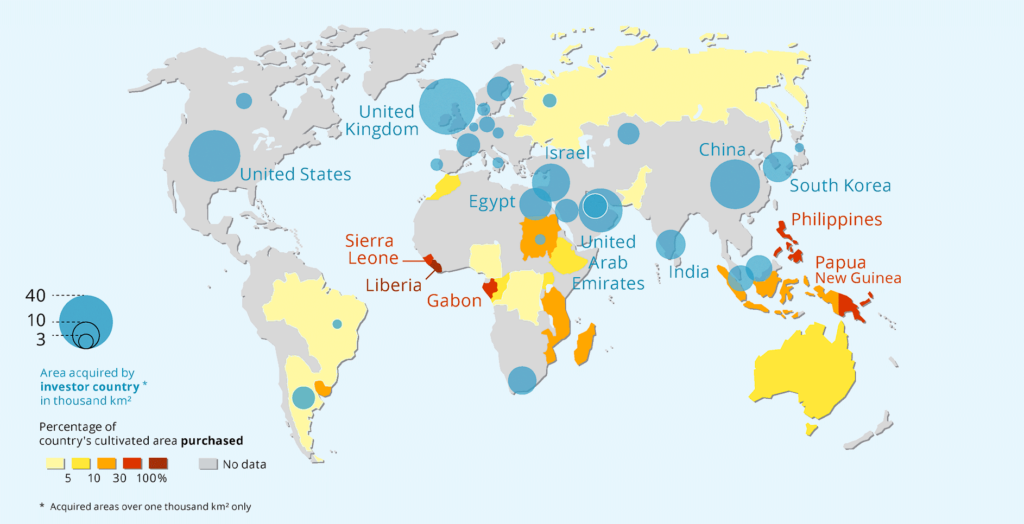

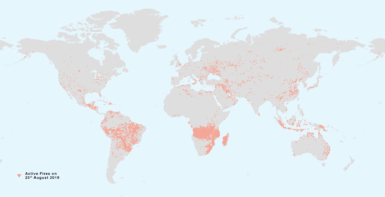

The term grabbing was adopted because of the lack of transparency in the set-up of land deals, their dubious legitimacy vis-à-vis communities who until then used these areas, and the dispossession the latter suffered once the deals were implemented. Estimates vary from 20 to 45 million hectares transacted between 2005 and 2010; the most recent estimates are around 30 million hectares in 78 countries. Actually, the calculation of grabbed areas has proven extremely challenging. Information is rarely disclosed given the controversial nature and the lack of legitimacy of those deals. Moreover, land grabs include not only transnational large-scale ones but also a broad range of national and local medium- and small-size land acquisitions that are hard to quantify.

Source (except for “land degradation neutrality” and “land grabbing”: © FAO, “FAO Soils Portal”, accessed 8 November 2019, http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/about/all-definitions/en/.

Breakdown of the Global, Ice-Free Land Surface (130 million km2)

Source: IPCC, Climate Change and Land (August 2019), 4.