Land Grabs, Big Business and Large-Scale Damages

The history of the world is a story of lands conquered by violence. Today, money has replaced weapons. Lands are bought. In very large quantities. The current wave of land grabbing is a phenomenon of hard conquest and a dramatic one for local populations and the environment.

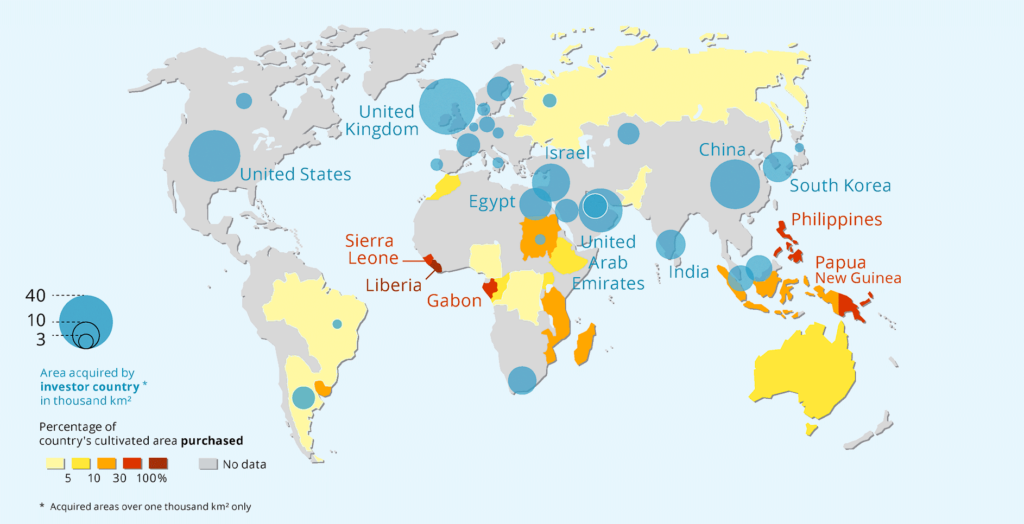

The current wave of land grabbing emerged in the second half of the 2000s in a context of increasing food prices and threats of food shortages for importing countries.

It became well-known in 2008 with the release of reports such as Seized! by the NGO Grain, and worldwide dataset such as the Land Matrix.Land grabbing has simultaneously been driven by the development of agrofuel crops and by speculative investment into agribusiness, especially after the 2008 financial crisis. A large number of large-scale land deals, involving up to dozens of thousands of hectares, were set up between “host” governments and various businesses, including agro-industrial companies, individuals, investment banks and hedge funds.

The Southeast Asian Case

In Southeast Asia, for example, to maintain their economic growth rates, China and Vietnam need land and natural resources (food, feed for livestock, wood, hydroelectricity), which they “find” at a low price in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. In exchange of land concessions, the two advanced economies provide financial resources to the three others, and, no less important, political support to the elites and the regime. At the national level, land grabs hinge on inequalities between, on the one side, power holders including the government, the army, non-governmental armed groups (in Myanmar), political factions as well as private actors connected to them, and, on the other side, ordinary populations lacking the power to assert their original land use rights or to resort to judicial systems.The imbalance of power between these two segments of population determines the magnitude of land grabs: in Vietnam, formal land tenure (long-term land use rights granted from the 1993 Land Law) has offered relative protection to small landholders from land grabs; in Myanmar, on the contrary, poorly protected land rights have led to the extreme case of hundreds of thousands Rohingyas being deprived of any recognition and expulsed from the country.

environmental Consequences

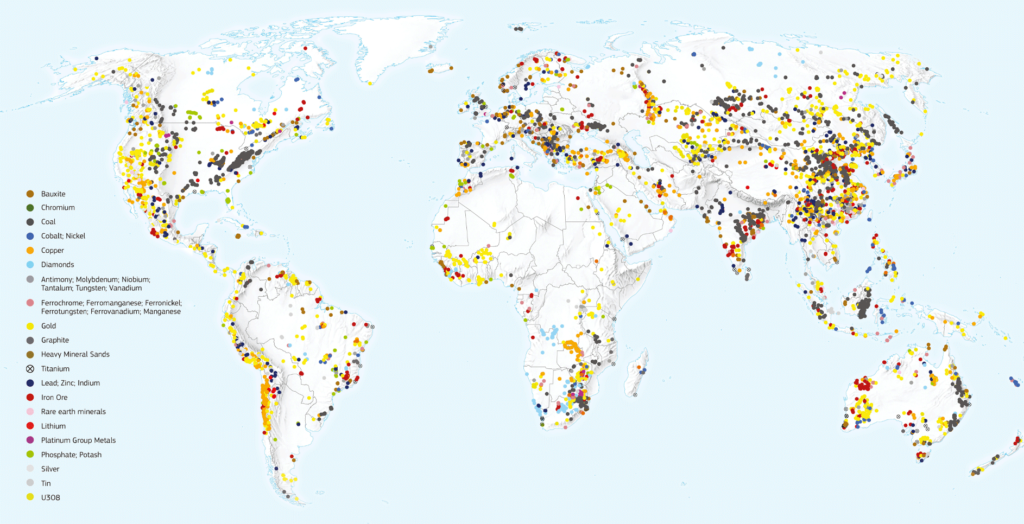

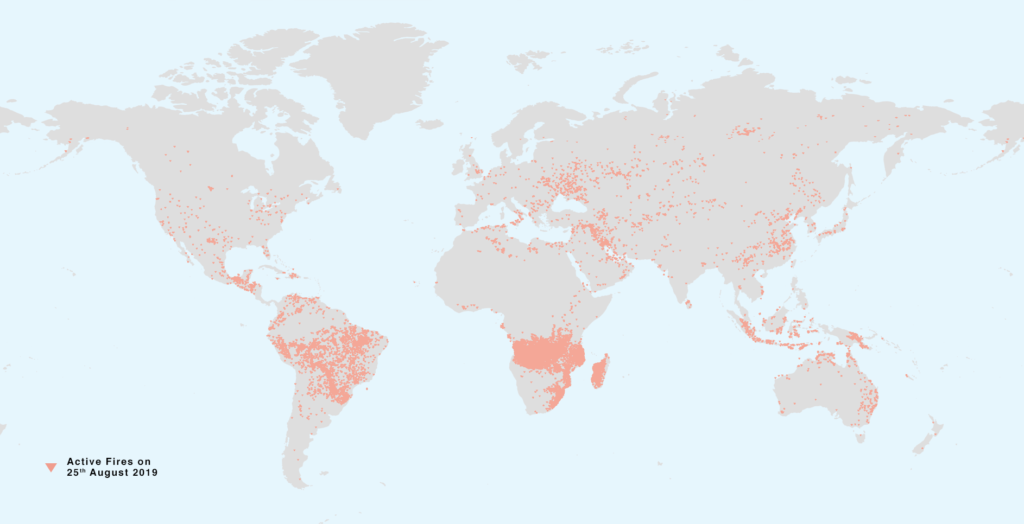

First, large-scale capital-intensive farming leads to deforestation, erosion and loss of biodiversity as forest areas and agroforestry systems are replaced by monoculture plantations. Input-intensive monoculture is also associated with chemical contamination and water pollution (Balehegn 2015). The territorial expansion of palm oil production on millions of hectares in Indonesia provides ample evidence of such detrimental environmental impact (Bissonnette 2016; see also Spieldoch and Murphy’s contribution in Kugelman and Levenstein 2009: 39–53); Daniel and Mittal 2010; Cotula 2013). Environmental degradation induced by land grabbing has impacted countries in the region differently: while Thailand and Vietnam have witnessed a slowdown in forest loss – and even reforestation in the case of Vietnam – land grabbing has led to an increase in the pace of deforestation in neighbouring Laos and Cambodia (De Koninck and Rousseau 2012: 18). Land grabs must thus be understood as “green grabs”, which is the appropriation of whole ecosystems with natural resource extraction as core rationale.

Second, land grabs force smallholders to resort to farming systems and rapid repayment strategies (or return on investment) that are unsustainable, for instance repeated cultivation of the same plant (because there is a demand) or insufficient fertilizer amendment because they do not have enough financial resource. Moreover, the productive potential of smallholders often remains unachieved, as they have to sell prematurely their harvest (lower output) or to sell it in advance sale (at a lower price).

Social Consequences

The magnitude of land grabbing and the severity of its consequences for communities vary greatly and are contingent on local power constellations. In some cases, communities lose all as they are expulsed and displaced without any compensation; in other cases, they are left with some land and time to (try to) adapt. Yet, overall, the early concerns about the threats land grabs pose to small landholders have been confirmed, including negative impacts on income, the undermining of livelihoods, the erosion of community-based social security mechanisms, and the weakening of adaptive capacity and resilience (Hak et al. 2018).

Land grabs must thus be understood as “green grabs”, which is the appropriation of whole ecosystems with natural resource extraction as core rationale. Land grabs are more than the large-scale land deals we tend to focus on. They contribute to broader land redistribution within communities, including grabs, encroachment, conflicts between socio-economic well-off elites allied to local authority and ordinary populations. They also impede pro-poor land reform. Inequalities increase as elites command the financial resources and social capital necessary to engage into new crops and crop-booms-related businesses. The majority of smallholders, on the contrary, suffers loss of farming land and access to the natural resources sustaining their livelihoods, while the new opportunities remain largely out of their reach (Gironde and Senties Portilla 2015). The outcome for many is increasing indebtedness and vulnerability vis-à-vis markets, banks and money lenders, which compels many of them to become wage workers for the better-off.

Conclusion

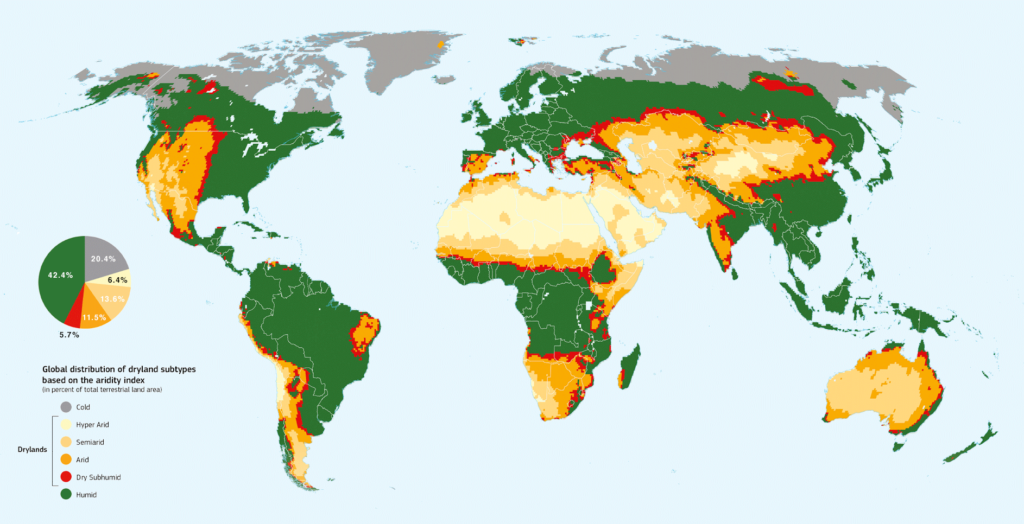

Compared to the 2000s, one can note today a slowdown of the largest land deals, but an increase of the numbers of overall transactions (Grain 2016). The international community has not done anything that really addresses land grabs and their dramatic environmental and social impacts. This trend is due to the exhaustion of available and accessible lands, the withdrawal of investors discouraged by unsatisfactory returns, the versatility of agricultural commodity markets and the resistance from communities. However, the smaller and medium-sized land deals persist at a steady pace as in-migrants, businessmen and entrepreneurs acquire lands from vulnerable smallholders – often unable to follow the requirements of commercial agriculture – and encroach on the frontiers of forests, steppes or deserts. The future of land grabbing is therefore hard to predict. Hitherto, the international community has not done anything that really addresses land grabs and their dramatic environmental and social impacts. Laconic calls for good governance and the FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Responsible Investment remain confined to the headquarters and administrations of international organisations, without inducing significant change in the powerful dynamics of land grabs.

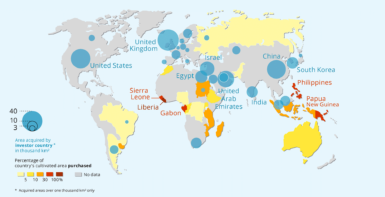

Global reported land deals, 2001–2011

Source: Oxfam, CIRAD, CDE at University of Bern, International Land Coalition.

Definition and estimates of land grabs

The term grabbing was adopted because of the lack of transparency in the set-up of land deals, their dubious legitimacy vis-à-vis communities who until then used these areas, and the dispossession the latter suffered once the deals were implemented. Estimates vary from 20 to 45 million hectares transacted between 2005 and 2010; the most recent estimates are around 30 million hectares in 78 countries. Actually, the calculation of grabbed areas has proven extremely challenging. Information is rarely disclosed given the controversial nature and the lack of legitimacy of those deals. Moreover, land grabs include not only transnational large-scale ones but also a broad range of national and local medium- and small-size land acquisitions that are hard to quantify.

Land degradation | Key terms

Like many common words, the word soil has several meanings. In its traditional meaning, soil is the natural medium for the growth of plants. Soil has also been defined as a natural body consisting of layers (soil horizons) that are composed of weathered mineral materials, organic material, air and water. Soil is the end product of the combined influence of climate, topography and organisms (flora, fauna and human) on parent materials (original rocks and minerals) over time. As a result, soil differs from its parent material in texture, structure, consistency, color, chemical, biological and physical characteristics. Soil is an essential component of land and eco-systems, which both are broader concepts encompassing vegetation, water and climate in the case of land, and in addition to those three aspects, also social and economic considerations in the case of ecosystems.

The word soil is also known as dirt, waste or earth.

Soil erosion is a common term that is often confused with soil degradation as a whole, but in fact refers only to absolute soil losses in terms of topsoil and nutrients. This is indeed the most visible effect of soil degradation, but it does not cover all of its aspects. Soil erosion is a natural process in mountainous areas, but is often made much worse by poor management practices.

Land degradation has a wider scope than both soil erosion and soil degradation in that it covers all negative changes in the capacity of the ecosystem to provide goods and services (including biological and water-related goods and services, and, in the vision of LADA – Land Degradation Assessment in Dryland – also land-related social and economic goods and services).

Desertification is another common term used for (a) land degradation in dryland areas and/or (b) the irreversible change of the land to such a state it can no longer be recovered for its original use.

Mitigation is intervention intended to reduce ongoing degradation. This comes in at a stage when degradation has already begun. The main aim is to halt further degradation and to start improving resources and their functions. Mitigation impacts tend to be noticeable in the short-to-medium term: this then provides a strong incentive for further efforts. The word mitigation is also sometimes used to describe the reductions of impacts of degradation.

Rehabilitation is required when the land is already degraded to such an extent that the original use is no longer possible and the land has become practically unproductive. Longer-term and often more costly investments are needed to show any impact.

Land degradation neutrality describes the state whereby the amount and quality of land resources, necessary to support ecosystem functions and services and enhance food security, remains stable or increases within specified temporal and spatial scales and ecosystems (source: UNCDD).

The term grabbing was adopted because of the lack of transparency in the set-up of land deals, their dubious legitimacy vis-à-vis communities who until then used these areas, and the dispossession the latter suffered once the deals were implemented. Estimates vary from 20 to 45 million hectares transacted between 2005 and 2010; the most recent estimates are around 30 million hectares in 78 countries. Actually, the calculation of grabbed areas has proven extremely challenging. Information is rarely disclosed given the controversial nature and the lack of legitimacy of those deals. Moreover, land grabs include not only transnational large-scale ones but also a broad range of national and local medium- and small-size land acquisitions that are hard to quantify.

Source (except for “land degradation neutrality” and “land grabbing”: © FAO, “FAO Soils Portal”, accessed 8 November 2019, http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/about/all-definitions/en/.

Breakdown of the Global, Ice-Free Land Surface (130 million km2)

Source: IPCC, Climate Change and Land (August 2019), 4.