Aerial Occupation and Aerial Forensics in Gaza

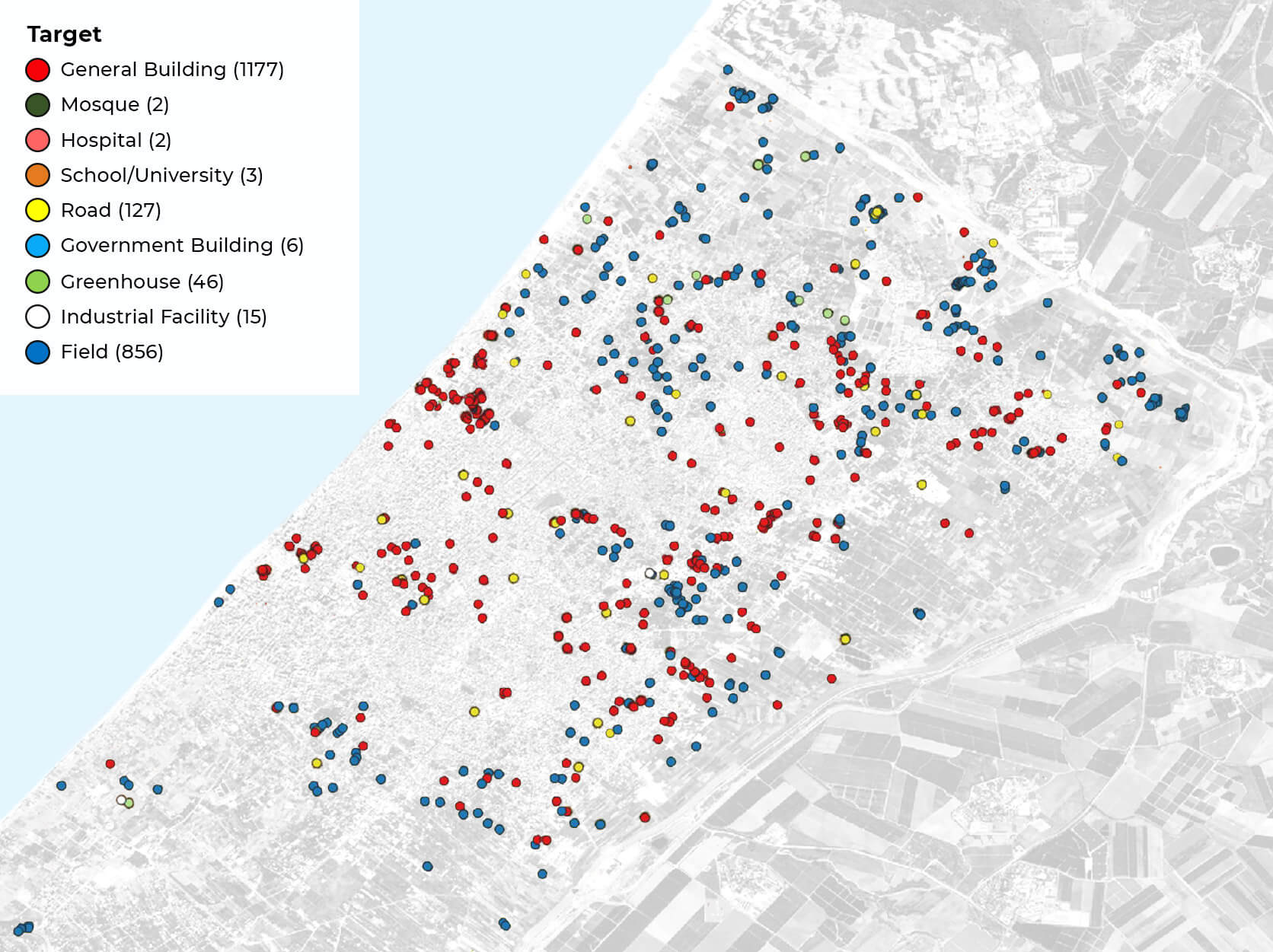

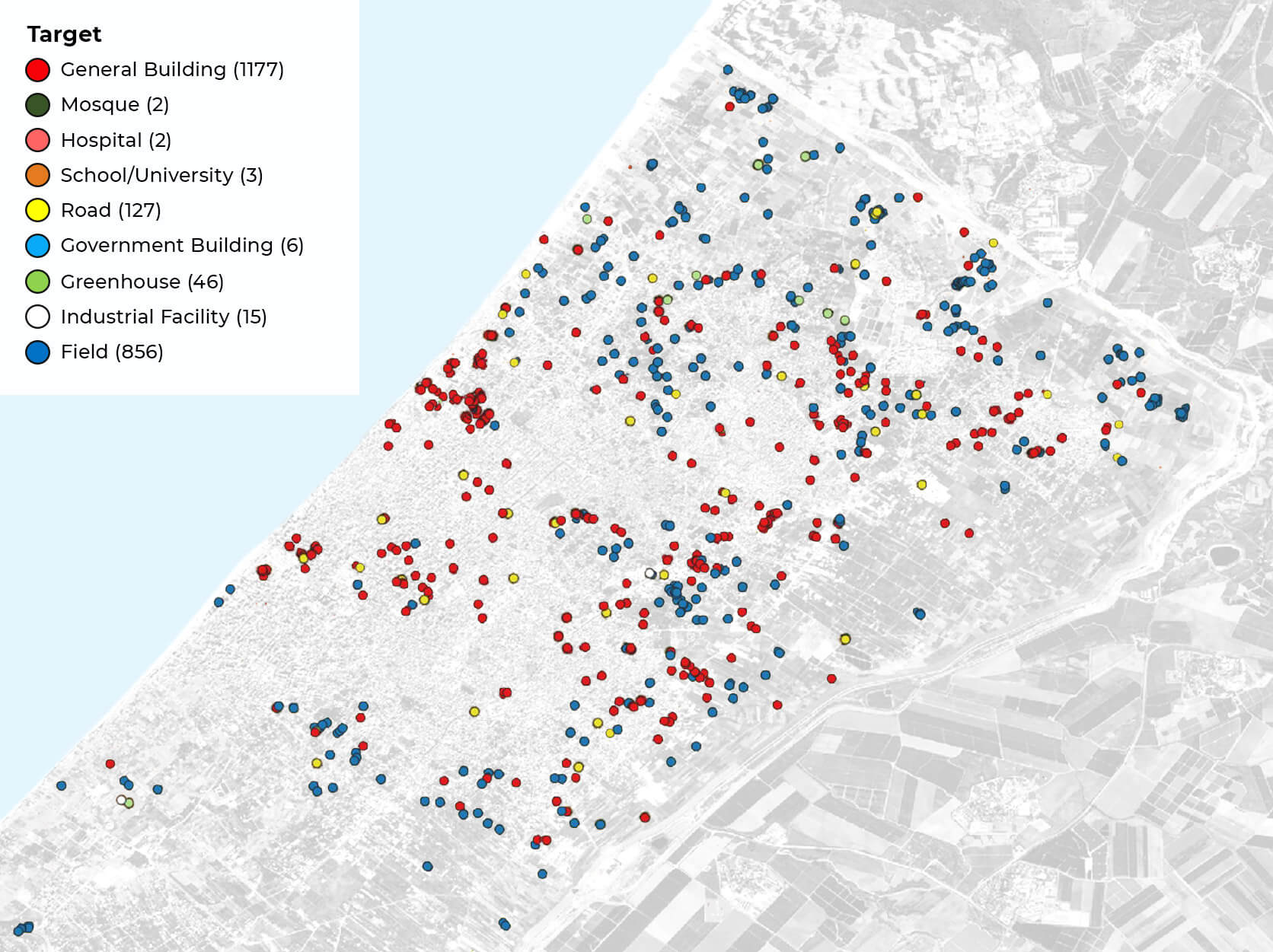

Figure 2 : Visualization of UNOSAT damage assessment in Northern Gaza from May 20 and 28, 20 21 on Sentinel II imagery

ESA, 2023; UNOSAT, 05.06.2021

ESA, 2023; UNOSAT, 05.06.2021

While the 20th century has been characterised by the generalisation of democratisation processes, the 21st century seems to have started with the reverse trend. An authoritarian-populist nexus is threatening liberal democracy on a global scale, including in its American and European heartlands. Charismatic leaders – thriving on electoral majorities and popular referenda – methodically undermine the rule of law and constitutional safeguards in order to consolidate their own power basis. Coupling inflammatory rhetoric with modern communication technologies, they short-circuit traditional elites and refuse to abide by international norms. Agitating contemporary scourges such as insecurity, loss of identity, mass migration and corrupt elites, they put in place new laws and mechanisms to harness civil society and political opponents. In order to better understand the novelty, permanence and global reach of “illiberal democracy”, this second issue of Global Challenges proposes seven case studies (Russia, Hungary, Turkey, the Middle East, Uganda, Venezuela and the United States) complemented by a series of expert interviews, maps and infographics.

Has globalisation reached its apex after centuries of growth as suggested by the latest figures of the WTO? In the affirmative, does this imply that we are ushering into a new era of degrowth? Or are we witnessing the reorganisation of the very architecture of globalisation, which remains based on the twin logic of the acceleration and continuous increase of the volume of exchanges, as well as the steady densification of geographic connectedness. Are global exchanges restructuring concomitantly to the fourth technological revolution and the expansion of the digital economy? The present Dossier proposes to approach this question by observing the nature and the evolution of the principal flows that characterise globalisation.

Today, we observe a renewed interest in the theme of decolonisation in three interrelated fields: in the academic world which opens new areas of research and teaching (e.g. decolonisation studies; decolonising the curriculum), in the practice of professionals and international actors who are revisiting their way of working, as well as in the vocabulary and activism of civil society targeting the remnants of colonial times such as street names, statues or museum objects. The renewed focus on decolonisation brings forth underlying issues such as the lingering of Eurocentrism, continued oppression of indigenous people, cultural relativism, the ongoing materiality of colonialism, the guilt of the West or, more generally, “the darker side of Western modernity”. While decolonisation has had a lasting impact on the political scene (with the decolonisation movements of the 1960s) and theoretically in the realm of academia, it lags behind in practice as processes, mentalities and epistemes are still permeated by “coloniality”. The present issue puts therefore decolonisation into historical perspective and provides fresh analytical perspectives on its epistemologies and methodologies as well as its practical application and consequences in various fields.

This issue has been coproduced by the Graduate Institute’s Department of International History and Politics and the Research Office. It also includes contributions from other research centres and departments of the Institute.