“Dezinformatsiya” and Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference

On 16 March 2022, President Putin gave a long speech in which he made verbal attacks and strong accusations against the “neo-Nazis” in Kiev. This was not the first time that the Russian authorities had referred to Ukraine and the West in these terms. During commemorations of the Siege of Leningrad on 18 January 2023 and the Battle of Stalingrad on 2 February 2023, President Putin stated that “many European countries took part in the Siege of Leningrad” and “practically all countries of subjugated Europe fought at Stalingrad”. “Today, again German [Western] tanks are on the way to fight Russians.” In this new version of history, the Soviet Union and the Western Allies did not fight together from 1941 to defeat Hitler.

Russian disinformation campaigns are part of a long tradition of foreign influence manipulation influence (FIMI) operations, in which states and their proxies conduct and coordinate information-based influence operations inside and outside their territory. Already after World War II, Joseph Stalin began to label those he considered a threat as “Nazi collaborators” and to remove them from the scene.. Already after World War II, Joseph Stalin began to label those he considered a threat as “Nazi collaborators” and to remove them from the scene. For more clarity in analysing such operations, Camille François and James Pamment propose the unbundling of FIMI incidents in terms of their actors, behaviours, content, degree and impact.

The Russian disinformation ecosystem consists of five pillars: official government communications; Russian state-funded media (e.g., RT and Sputnik) and sociocultural foundations; proxy sources, including Russia-aligned media outlets and proliferators of Russian narratives; the weaponisation of social media; and cyber-enabled disinformation. The editor-in-chief of RT, Margarita Simonyan, has defined RT’s mission in military terms, declaring its ability to wage an information war against the entire Western world using the weapon of information. The Wagner Group, a private Russian military contractor, began operating in Ukraine in 2013 by creating local media to spread disinformation and civil unrest.

Map showing countries’ official stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as of March 3, 2022.

Map showing countries’ official stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as of March 3, 2022.In 2012, President Putin and Maj. Gen. Sergei Kuralenko – then Chief of Military Art at the Academy of the General Staff – described information technology as a new tool for the military. They stated that “the development of information technologies has caused significant changes in the ways wars are fought and led to a build-up of cyber-troops”.

Online platforms have enabled a reality where every war zone becomes a global battlefield.Online platforms have enabled a reality where every war zone becomes a global battlefield. Online disinformation is mostly spread through (1) bots – computer programmes that automate content distribution; (2) paid, organised, and monitored trolls – human operators who falsify their true identities to spread discord; and (3) cyborgs – accounts managed by humans but sometimes taken over by bots or exhibiting bot-like or malicious behaviour.

In the context of the war in Ukraine, the most common narratives spread through the Russian disinformation ecosystem are: the West is the aggressor and is profiting from the war; Ukraine committed atrocities and provoked the war; sanctions against Russia are backfiring, with particular emphasis on the food and energy crisis and inflation; the West is hypocritical, corrupt, colonialist and Russophobic; and Ukraine is a Nazi and terrorist state. Most disinformation content is spread in the form of fabricated images and videos, as well as through the impersonation of media outlets and officials. For instance, some video content ascribed to reputable media claimed that Ukrainian football fans were detained over “Nazi symbols” in Doha during the World Cup,Some video content ascribed to reputable media claimed that Ukrainian football fans were detained over “Nazi symbols” in Doha during the World Cup. and that people could pay a German auction house to destroy Russian art. The online campaign #StopKillingDonbass draws attention to alleged crimes by the Ukrainian army against local populations. Graphic images and videos of corpses of minors and injured individuals, and videos to call populations to take to the street and protest flourish on social media platforms such as Telegram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and TikTok, as well as on Russia-aligned media outlets.

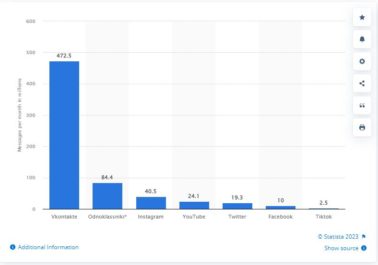

Most used social media in Russia in 2023

Most used social media in Russia in 2023Fabricated content is disseminated across multiple media and online platforms, including political news and entertainment channels. The Russian disinformation ecosystem is characterised by the close relationship between the government, official media outlets (including RT and Sputnik) and broader criminal networks,The Russian disinformation ecosystem is characterised by the close relationship between the government, official media outlets (including “RT” and “Sputnik”) and broader criminal networks. such as the Russian Business Network, and the degree of immunity they enjoy. Disinformation narratives are further amplified through formal diplomatic channels. The ban on Russian state-funded media in the EU may explain the reason for the increased use of diplomatic social media accounts.

Combined, these techniques aim to deceive populations and decision-makers by artificially supporting what seems like a trend, a consensus, a hashtag, a public figure, a piece of news, a view of the truth. As some scholars have recently pointed out, “[d]isinformation campaigns thereby overwhelm the ‘signal’ of actual news with ‘noise’, eroding the trust in news necessary for democracy to work”, one piece of false news at a time. And to quote General Ion Mihai Pacepa, who in 1978 was one of the highest-ranking officials to leave the Communist bloc, on the impact of dezinformatsiya: “a drop makes a hole in a stone not by force, but by constant dripping”.

PODCAST: The Right of Freedom in Armed Conflicts: A View from the United Nations, with Paige Morrow

RO Geneva Graduate Institute.

PODCAST: The link between political message and social context, with Michelle Weitzel

RO, Geneva Graduate Institute

DEFINITIONS | Some terms in the world of disinformation

An unfair practice of propaganda and manipulation used in the media and particularly on the internet, consisting of giving the impression of a mass phenomenon that emerges spontaneously when in reality it has been created from scratch to influence public opinion. (Source: Wiktionnaire, s.v. “astroturfing”.)

Computational propaganda involves the “use of algorithms, automation, and human curation to purposefully distribute misleading information over social media networks” (Woolley & Howard 2018). While propaganda has existed throughout human history, the rise of digital technologies and social media platforms have brought new dimensions to this practice (Source: Programme on Democracy & Technology of the Oxford Internet Institute, “What Is Computational Propaganda?”.)

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy by powerful and sinister groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable. The term generally has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice, emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence. A conspiracy theory is distinct from a conspiracy; it refers to a hypothesised conspiracy with specific characteristics, including, but not limited to, opposition to the mainstream consensus among those who are qualified to evaluate its accuracy, such as scientists or historians. (Source: Wikipedia, “Conspiracy Theory”.)

Black propaganda is intended to create the impression that it comes from those it is supposed to discredit. Black propaganda contrasts with grey propaganda, which does not identify its source, as well as white propaganda, which does not disguise its origins at all. It is typically used to vilify or embarrass the enemy through misrepresentation. The major characteristic of black propaganda is that the audience are not aware that someone is influencing them, and do not feel that they are being pushed in a certain direction. This type of propaganda is associated with covert psychological operations. Black propaganda is the “big lie”, including all types of creative deceit. Black propaganda relies on the willingness of the receiver to accept the credibility of the source. (Wikipedia, “Black Propaganda”.)

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but not deliberately so. Disinformation is presented in the form of fake news. Disinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix dis- to information, to create the meaning “reversal or removal of information”. Disinformation attacks involve the intentional dissemination of false information, with an end goal of misleading, confusing, or manipulating an audience. They may be executed by political, economic or individual actors to influence state or non-state entities and domestic or foreign populations. These attacks are commonly employed to reshape attitudes and beliefs, drive a particular agenda, or elicit certain actions from a target audience. Tactics include the presentation of incorrect or misleading information, the creation of uncertainty, and the undermining of both correct information and the credibility of information sources. (Sources: Wikipedia, “Disinformation” and “Disinformation Attack”.)

Fake news

Fake news is false or misleading information presented as news. Fake news often has the aim of damaging the reputation of a person or entity, or making money through advertising revenue. Although false news has always been spread throughout history, the term fake news was first used in the 1890s when sensational reports in newspapers were common. Nevertheless, the term does not have a fixed definition and has been applied broadly to any type of false information. It has is also been used by high-profile people to apply to any news unfavourable to them. In some definitions, fake news includes satirical articles misinterpreted as genuine, and articles that employ sensationalist or clickbait headlines that are not supported in the text. Because of this diversity of types of false news, researchers are beginning to favour information disorder as a more neutral and informative term. (Source: Wikipedia, “Fake News”.)

IMT is a theory of deceptive discourse production, arguing that, rather than communicators producing “truths” and “lies”, the vast majority of everyday deceptive discourse involves complicated combinations of elements that fall somewhere in between these polar opposites; with the most common form of deception being the editing-out of contextually problematic information (i.e., messages commonly known as “white lies”). More specifically, individuals have available to them four different ways of misleading others: playing with the amount of relevant information that is shared, including false information, presenting irrelevant information, and/or presenting information in an overly vague fashion. (Source: Wikipedia, “Information Manipulation Theory”.)

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. It differs from disinformation, which is deliberately deceptive. Misinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix mis- to information, to create the meaning “wrong of false information”. Rumours, by contrast, are information not attributed to any particular source, and so are unreliable and often unverified, but can turn out to be either true or false. Even if later retracted, misinformation can continue to influence actions and memory. People may be more prone to believe misinformation if they are emotionally connected to what they are listening to or are reading (Source: Wikipedia, “Misinformation”.)

Mute news is a pernicious form of information in which a key issue that often underlies the concerns of the public and the body politic is obscured from media attention. (Source: Lê Nguyên Hoang and Sacha Altay, “Disinformation: Emergency or False Problem?”, Polytechnique Insights, 6 September 2022.)

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is being presented. In the 20th century, propaganda was often associated with a manipulative approach, but historically, propaganda has been a neutral descriptive term of any material that promotes certain opinions or ideologies. (Source: Wikipedia, “Propaganda”.)

Typosquatting, also called URL hijacking, a sting site or a fake URL, is a form of cybersquatting, and possibly brandjacking, which relies on mistakes such as typos made by Internet users when inputting a website address into a web browser. Should a user accidentally enter an incorrect website address, they may be led to any URL (including an alternative website owned by a cybersquatter). (Source: Wikipedia, “Typosquatting”.)

PODCAST: The Difference between Russian and Ukrainian propaganda, Svitlana Ovcharenko

Research Office. Geneva Graduate Institute.

PODCAST: (Dis)Information as a tool of warfare, with Jean-Marc Rickli

Research office. Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST: Mobilization from below to face the control in authoritarian states, with G. O. and V. Neeraj

Research Office. Geneva Graduate Institute.