Vulgar Vibes: The Atmospheres of the Global Disinformation Order

In his speech at the celebrations of the bicentenary of the Brazilian Republic, President Bolsonaro explained to the crowd that had gathered for the solemn occasion that men should get themselves women to stop being unhappy. After demonstratively turning to kiss the First Lady, Michelle, the President declared that he was “imbrochável” – Brazilian slang for having a lasting hard-on. He started chanting “imbrochável, imbrochável, imbrochável…”. The people who had gathered joined in. The video of the event quickly spread on social media and into the mainstream news. The vulgarity of the chanting was striking and provocative. It scandalised the prude, broke with the conventions of the celebration, and debased all/any sensibility towards gender. This scene also directs our attention to the importance of the atmospheres underpinning the Global Disinformation Order and to the urgent and challenging question of how this order might be engaged, including through regulatory politics.

Let us pause to consider why Bolsonaro’s chanting attracted attention. Clearly, the quality and truth of the information were not the core points. Zealous journalists dutifully proceeded to interview the First Lady, asking her if it was really true that the President was “imbrochável”. She assured them it was. That exchange, however, appeared rather absurd and out of touch. No one really cared about the truthfulness of Bolsonaro’s affirmation. Preoccupying were the vulgar vibes of the performance and the way they infused the political atmosphere. They enshrined and fuelled the polarised and often violent identity politics of race, indignity, sexual orientation, class, education, religion and more that occupies a central place in Brazil and beyond.They also perpetuated a form of politics where moods rather than arguments matter They also perpetuated a form of politics where moods rather than arguments matter. Bolsonaro and the enthusiastic crowd chanting with him were not deliberating or reasoning about identity politics. They were setting the tone for it. Vibes, tone, mode, atmospheres. We are far away not only from the conventional vocabulary of politics but also from the terms usually associated with the Global Disinformation Order. Considering that Bolsonaro’s “imbrochável” chanting is but one of innumerable instances of performances generating masculinist/sexist resonances and, given the all-pervasive character of atmospheric politics, the conclusion is that we need to rethink the terms on which we think about and get involved with disinformation. We need to focus more on atmospheres.

This shift towards a focus on atmospheres is no abstract exercise for academics alone. It is fundamentally important for engaging the Global Disinformation Order. The vibes of vulgarity enshrined in Bolsonaro’s chanting not only accentuate polarisation but contribute to a political atmosphere where statements about “having a lasting hard-on” or “grabbing pussies” or posting sexually charged images of yourself (make your own choice from a disturbingly rich repertoire inspired by Salvini, Trump and Putin among many others) have become commonplace. More than setting the tone, the vibes create an environment where debasing images and claims occupy centre stage. Images intimating the rape of former President Dilma as well as rumours about the Labour Party imposing homosexuality on the school curriculum or promoting a baby bottle shaped as a penis are examples from Bolsonaro’s 2018 campaign. In this atmosphere, disinformation is not an aberration. It is a logical and crucial part of politics. Wild rumours and conspiracy theories such as those related to Democrats in the US running a child sex-ring in the basement of a pizzeria (“Pizzagate”) make sense as contributing to the creation of affective political communities. They feed the flow of vibes infusing the atmospheres sustaining these communities.

Online atmospheres can be – and are − strategically manipulated. Bolsonaro relied on specialised agencies and a range of activists in his 2018 campaign. They ensured that his messages reached the intended audiences. Other politicians, organisations and researchers do likewise.If we want to come to terms with this order, we therefore need to shift attention from issues of information veracity, deep fakes, bots, trolls or the debasing vulgarity of individual statements to the atmospheres in which these emerge and prosper. The “Cambridge Analytica scandal”, where a company was systematically manipulating personal data to help those wishing to target specific audiences (potential voters or consumers), has come to epitomise such manipulation. It underscores that the manipulation of atmospheres is not exclusively about infusing them with masculinist/sexist vibes, of course. Rather, it is a widespread manipulation of moods that feed and reinforce a Global Disinformation Order sustained by the perpetuation of the atmospheres on which it thrives. If we want to come to terms with this order, we therefore need to shift attention from issues of information veracity, deep fakes, bots, trolls or the debasing vulgarity of individual statements to the atmospheres in which these emerge and prosper.

So what exactly does this amount to? Working with the atmospheres, redesigning them in order to cut out the vulgar vibes infusing them, including those generated by chanting “imbrochável” at the bicentenary of the Republic. This is obviously a complex task that requires rethinking the operations of the digital infrastructures and their technological affordances. Awareness of the need for such work is extensive.

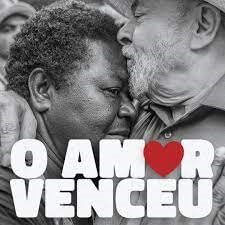

In politics, those resisting polarisation are trying to shift the atmospheres, working with digital infrastructures. Current President Lula made “love” core to his 2022 electoral campaign and its associated paraphernalia, which were replete with references to “amor” (love in Portuguese). When Lula acknowledged victory on election night, his televised speech opened with references to love. “Love will win” became “Love has won” on his official website:

Analogously, many organisations, spanning the full range from the large platforms – the GAFAM – to public institutions, are developing ideas for how to redesign digital infrastructures so as to reduce polarisation and violence. The Brazilian Superior Electoral Court has established a “Permanent Program on Countering Disinformation”. In collaboration with a range of actors including online service providers, civil society organisations and political parties, the program adopted a strategic plan with actions discouraging disinformation, inscribing them in the digital infrastructures. These actions include central reporting systems and fact-checking services. They also include a range of measures ensuring “a healthier information environment during elections”.

The Brazilian programme for countering disinformation will certainly evolve and require revisions. It is no more a panacea than is Lula’s focus on love. However, they are examples of how the Global Challenges of engaging with the atmospheres of the Global Disinformation Order are being tackled and will have to be tackled if we wish to curb the most nefarious consequences of the Global Disinformation Order and instead enhance the other − positive and progressive − role of our Global Information Order.

Bolsonaro chanting “imbrochável” with the crowd

Stills from video recording available on www.youtube.com (accessed 3 April 2023).

PODCAST: The Right of Freedom in Armed Conflicts: A View from the United Nations, with Paige Morrow

RO Geneva Graduate Institute.

PODCAST: The link between political message and social context, with Michelle Weitzel

RO, Geneva Graduate Institute

DEFINITIONS | Some terms in the world of disinformation

An unfair practice of propaganda and manipulation used in the media and particularly on the internet, consisting of giving the impression of a mass phenomenon that emerges spontaneously when in reality it has been created from scratch to influence public opinion. (Source: Wiktionnaire, s.v. “astroturfing”.)

Computational propaganda involves the “use of algorithms, automation, and human curation to purposefully distribute misleading information over social media networks” (Woolley & Howard 2018). While propaganda has existed throughout human history, the rise of digital technologies and social media platforms have brought new dimensions to this practice (Source: Programme on Democracy & Technology of the Oxford Internet Institute, “What Is Computational Propaganda?”.)

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy by powerful and sinister groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable. The term generally has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice, emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence. A conspiracy theory is distinct from a conspiracy; it refers to a hypothesised conspiracy with specific characteristics, including, but not limited to, opposition to the mainstream consensus among those who are qualified to evaluate its accuracy, such as scientists or historians. (Source: Wikipedia, “Conspiracy Theory”.)

Black propaganda is intended to create the impression that it comes from those it is supposed to discredit. Black propaganda contrasts with grey propaganda, which does not identify its source, as well as white propaganda, which does not disguise its origins at all. It is typically used to vilify or embarrass the enemy through misrepresentation. The major characteristic of black propaganda is that the audience are not aware that someone is influencing them, and do not feel that they are being pushed in a certain direction. This type of propaganda is associated with covert psychological operations. Black propaganda is the “big lie”, including all types of creative deceit. Black propaganda relies on the willingness of the receiver to accept the credibility of the source. (Wikipedia, “Black Propaganda”.)

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but not deliberately so. Disinformation is presented in the form of fake news. Disinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix dis- to information, to create the meaning “reversal or removal of information”. Disinformation attacks involve the intentional dissemination of false information, with an end goal of misleading, confusing, or manipulating an audience. They may be executed by political, economic or individual actors to influence state or non-state entities and domestic or foreign populations. These attacks are commonly employed to reshape attitudes and beliefs, drive a particular agenda, or elicit certain actions from a target audience. Tactics include the presentation of incorrect or misleading information, the creation of uncertainty, and the undermining of both correct information and the credibility of information sources. (Sources: Wikipedia, “Disinformation” and “Disinformation Attack”.)

Fake news

Fake news is false or misleading information presented as news. Fake news often has the aim of damaging the reputation of a person or entity, or making money through advertising revenue. Although false news has always been spread throughout history, the term fake news was first used in the 1890s when sensational reports in newspapers were common. Nevertheless, the term does not have a fixed definition and has been applied broadly to any type of false information. It has is also been used by high-profile people to apply to any news unfavourable to them. In some definitions, fake news includes satirical articles misinterpreted as genuine, and articles that employ sensationalist or clickbait headlines that are not supported in the text. Because of this diversity of types of false news, researchers are beginning to favour information disorder as a more neutral and informative term. (Source: Wikipedia, “Fake News”.)

IMT is a theory of deceptive discourse production, arguing that, rather than communicators producing “truths” and “lies”, the vast majority of everyday deceptive discourse involves complicated combinations of elements that fall somewhere in between these polar opposites; with the most common form of deception being the editing-out of contextually problematic information (i.e., messages commonly known as “white lies”). More specifically, individuals have available to them four different ways of misleading others: playing with the amount of relevant information that is shared, including false information, presenting irrelevant information, and/or presenting information in an overly vague fashion. (Source: Wikipedia, “Information Manipulation Theory”.)

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. It differs from disinformation, which is deliberately deceptive. Misinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix mis- to information, to create the meaning “wrong of false information”. Rumours, by contrast, are information not attributed to any particular source, and so are unreliable and often unverified, but can turn out to be either true or false. Even if later retracted, misinformation can continue to influence actions and memory. People may be more prone to believe misinformation if they are emotionally connected to what they are listening to or are reading (Source: Wikipedia, “Misinformation”.)

Mute news is a pernicious form of information in which a key issue that often underlies the concerns of the public and the body politic is obscured from media attention. (Source: Lê Nguyên Hoang and Sacha Altay, “Disinformation: Emergency or False Problem?”, Polytechnique Insights, 6 September 2022.)

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is being presented. In the 20th century, propaganda was often associated with a manipulative approach, but historically, propaganda has been a neutral descriptive term of any material that promotes certain opinions or ideologies. (Source: Wikipedia, “Propaganda”.)

Typosquatting, also called URL hijacking, a sting site or a fake URL, is a form of cybersquatting, and possibly brandjacking, which relies on mistakes such as typos made by Internet users when inputting a website address into a web browser. Should a user accidentally enter an incorrect website address, they may be led to any URL (including an alternative website owned by a cybersquatter). (Source: Wikipedia, “Typosquatting”.)

PODCAST: The Difference between Russian and Ukrainian propaganda, Svitlana Ovcharenko

Research Office. Geneva Graduate Institute.

PODCAST: (Dis)Information as a tool of warfare, with Jean-Marc Rickli

Research office. Geneva Graduate Institute

PODCAST: Mobilization from below to face the control in authoritarian states, with G. O. and V. Neeraj

Research Office. Geneva Graduate Institute.