The Islamic State’s Virtual Caliphate

By the peak of its territorial caliphate in Iraq and Syria in 2015, the Islamic State had developed an unprecedented virtual caliphate that used social media and messaging platforms to disseminate its sophisticated video, written and audio propaganda content that sold the virtues of the Islamic State. This article focuses on the relationship between the physical and virtual caliphates and the adaptions made in the virtual caliphate in response to the fall of the Islamic State’s territory in Iraq and Syria.

The success of the Islamic State’s virtual caliphate is intertwined with the territorial success of the group. At the peak of its territorial control in Iraq and Syria in 2015, the Islamic State devoted much of its online content and communication strategy to selling the vision of its utopian state:At the peak of its territorial control in Iraq and Syria in 2015, the Islamic State devoted much of its online content and communication strategy to selling the vision of its utopian state. a religiously correct Islamic caliphate with the structures, services and efficacy that rivalled those of nation-states. Over half of its media output in 2015 focused on life under the caliphate, with specific series dedicated to its healthcare, social support and education provision.

As the Islamic State’s territory in Iraq and Syria diminished from 2017 onwards and the group moved from a modus operandi of state building to one of insurgency, the quantity and tone of its content and messaging changed correspondingly. By November 2017, over 90% of the Islamic State’s content revolved around its new form of insurgency warfare, with key narratives framing the Islamic State’s territorial defeat as immaterial, an inconsequential temporary blip in the longer conquest by jihad. As the now deceased spokesperson Abu Muhammad al-Adnani made clear in May 2016, “Do you, O America, consider defeat to be the loss of a city or the loss of land? Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq and were in the desert without any city or land? . . . Certainly not! True defeat is the loss of willpower and desire to fight.”

Aside from the shifts in narrative, the number of videos produced by the Islamic State is similarly linked to the territorial reality of the group. Analysis of the Islamic State’s video production shows that the group went from a peak of 81 videos published a month in April 2015 to a low of one video in June 2018.

A key factor behind this decline is the momentum-sapping defeats faced by the Islamic State and the loss of prestige around the Islamic State’s core in Iraq and Syria. The Islamic State’s video and print campaigns relied on the religiously symbolic narrative of establishing a caliphate that was given sustained momentum by the group’s military, territorial, recruitment and governance victories in Iraq and Syria. Over the past five years, however, the Islamic State in its Iraqi and Syrian territory has remained in a highly restricted insurgency phase. The current caliph, Abu al-Hussein al-Husseini al-Qurashi, remains widely unknown; he has never spoken or even appeared in any Islamic State messaging. With only a few notable operations, it has proved unable to regain its lost territory and had three caliphs killed. Indeed, the current caliph, Abu al-Hussein al-Husseini al-Qurashi, remains widely unknown; he has never spoken or even appeared in any Islamic State messaging. Put simply, there is not enough “positive” news or narrative for the Islamic State to maintain a fraction of the content it produced at its peak.

Undoubtedly the impact of the Islamic State’s digital caliphate today is significantly diminished. There are, however, two trends that have maintained the resiliency of the Islamic State online: the shift to the provinces and the decentralisation of media operations.

As the Islamic State lost its territory in Iraq and Syria, the group’s propaganda shifted to place greater attention on the group’s external provinces (wilayat), some of which have been operationally more successful in recent years. In 2022, the Islamic State claimed in al-Naba – its weekly newsletter – to have conducted 2,015 operations across all its provinces; most operations took place in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel (Islamic State’s West Africa Province and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara Province) region in Africa, followed by Iraq and then Afghanistan (Islamic State’ Khurasan Province). The successes in these provinces have dominated the centrally-produced Islamic State propaganda content and these provinces have begun to produce significant amounts of their own content.

One example is the Islamic State’s Khurasan Province, which created its own official media production office (al-Azaim Media Foundation), supported by at least six other propaganda units. It produces a regular magazine, Voice of Khurasan, which features increasingly transnational-orientated content in Pashto, Arabic, English and Dari, frequently translated into the Urdu, Hindi, Uighur, Uzbek and Tajik languages.

This is in addition to a regular stream of books and videos. This content produced by the external provinces is thereby a key pillar in replicating the propaganda strategy that made the Islamic State in its Iraqi and Syrian provinces so successful.

Finally, the Islamic State’s online supporters have been crucial to the maintenance of a “virtual caliphate” through the creation of decentralised communities outside of Iraq and Syria that maintain the online presence of the Islamic State. This shift to online decentralisation had to occur due to the loss of territory in Iraq and Syria, where the supporters who directed the online operations were previously located.

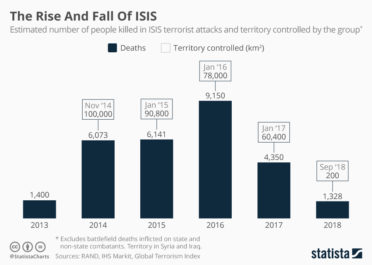

The rise and fall of ISIS. The figure shows the number of people killed in ISIS terrorist attacks and the amount of territory controlled by ISIS (in km2) from 2013 to 2018 (Statista, 10 December 2023)

The rise and fall of ISIS. The figure shows the number of people killed in ISIS terrorist attacks and the amount of territory controlled by ISIS (in km2) from 2013 to 2018 (Statista, 10 December 2023)These decentralised communities have developed significant network resilience, shown adaptability and have the ability to evade the content moderation of social media and messaging platforms. Decentralisation has thus been essential to ensuring the continuity of the Islamic State’s online presence, despite the group’s territorial losses and reduction in content.

In conclusion, it can be observed that, unlike other cases discussed in this Dossier, it is conceptually difficult to use the term “disinformation” when speaking about the Islamic State’s virtual caliphate. Certainly, the Islamic State has to adapt its propaganda to different audiences and to the territorial evolution of the caliphate over time. However, the Islamic State’s content and narrative need to remain consistently grounded in its belief system and its spiritual aspiration to establish a rightly guided caliphate. The aim therefore is not so much to spread disinformation and thereby confusion but to sell key messages to its targeted followers.

DEFINITIONS | Some terms in the world of disinformation

An unfair practice of propaganda and manipulation used in the media and particularly on the internet, consisting of giving the impression of a mass phenomenon that emerges spontaneously when in reality it has been created from scratch to influence public opinion. (Source: Wiktionnaire, s.v. “astroturfing”.)

Computational propaganda involves the “use of algorithms, automation, and human curation to purposefully distribute misleading information over social media networks” (Woolley & Howard 2018). While propaganda has existed throughout human history, the rise of digital technologies and social media platforms have brought new dimensions to this practice (Source: Programme on Democracy & Technology of the Oxford Internet Institute, “What Is Computational Propaganda?”.)

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy by powerful and sinister groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable. The term generally has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice, emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence. A conspiracy theory is distinct from a conspiracy; it refers to a hypothesised conspiracy with specific characteristics, including, but not limited to, opposition to the mainstream consensus among those who are qualified to evaluate its accuracy, such as scientists or historians. (Source: Wikipedia, “Conspiracy Theory”.)

Black propaganda is intended to create the impression that it comes from those it is supposed to discredit. Black propaganda contrasts with grey propaganda, which does not identify its source, as well as white propaganda, which does not disguise its origins at all. It is typically used to vilify or embarrass the enemy through misrepresentation. The major characteristic of black propaganda is that the audience are not aware that someone is influencing them, and do not feel that they are being pushed in a certain direction. This type of propaganda is associated with covert psychological operations. Black propaganda is the “big lie”, including all types of creative deceit. Black propaganda relies on the willingness of the receiver to accept the credibility of the source. (Wikipedia, “Black Propaganda”.)

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but not deliberately so. Disinformation is presented in the form of fake news. Disinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix dis- to information, to create the meaning “reversal or removal of information”. Disinformation attacks involve the intentional dissemination of false information, with an end goal of misleading, confusing, or manipulating an audience. They may be executed by political, economic or individual actors to influence state or non-state entities and domestic or foreign populations. These attacks are commonly employed to reshape attitudes and beliefs, drive a particular agenda, or elicit certain actions from a target audience. Tactics include the presentation of incorrect or misleading information, the creation of uncertainty, and the undermining of both correct information and the credibility of information sources. (Sources: Wikipedia, “Disinformation” and “Disinformation Attack”.)

Fake news

Fake news is false or misleading information presented as news. Fake news often has the aim of damaging the reputation of a person or entity, or making money through advertising revenue. Although false news has always been spread throughout history, the term fake news was first used in the 1890s when sensational reports in newspapers were common. Nevertheless, the term does not have a fixed definition and has been applied broadly to any type of false information. It has is also been used by high-profile people to apply to any news unfavourable to them. In some definitions, fake news includes satirical articles misinterpreted as genuine, and articles that employ sensationalist or clickbait headlines that are not supported in the text. Because of this diversity of types of false news, researchers are beginning to favour information disorder as a more neutral and informative term. (Source: Wikipedia, “Fake News”.)

IMT is a theory of deceptive discourse production, arguing that, rather than communicators producing “truths” and “lies”, the vast majority of everyday deceptive discourse involves complicated combinations of elements that fall somewhere in between these polar opposites; with the most common form of deception being the editing-out of contextually problematic information (i.e., messages commonly known as “white lies”). More specifically, individuals have available to them four different ways of misleading others: playing with the amount of relevant information that is shared, including false information, presenting irrelevant information, and/or presenting information in an overly vague fashion. (Source: Wikipedia, “Information Manipulation Theory”.)

Misinformation is incorrect or misleading information. It differs from disinformation, which is deliberately deceptive. Misinformation comes from the application of the Latin prefix mis- to information, to create the meaning “wrong of false information”. Rumours, by contrast, are information not attributed to any particular source, and so are unreliable and often unverified, but can turn out to be either true or false. Even if later retracted, misinformation can continue to influence actions and memory. People may be more prone to believe misinformation if they are emotionally connected to what they are listening to or are reading (Source: Wikipedia, “Misinformation”.)

Mute news is a pernicious form of information in which a key issue that often underlies the concerns of the public and the body politic is obscured from media attention. (Source: Lê Nguyên Hoang and Sacha Altay, “Disinformation: Emergency or False Problem?”, Polytechnique Insights, 6 September 2022.)

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded language to produce an emotional rather than a rational response to the information that is being presented. In the 20th century, propaganda was often associated with a manipulative approach, but historically, propaganda has been a neutral descriptive term of any material that promotes certain opinions or ideologies. (Source: Wikipedia, “Propaganda”.)

Typosquatting, also called URL hijacking, a sting site or a fake URL, is a form of cybersquatting, and possibly brandjacking, which relies on mistakes such as typos made by Internet users when inputting a website address into a web browser. Should a user accidentally enter an incorrect website address, they may be led to any URL (including an alternative website owned by a cybersquatter). (Source: Wikipedia, “Typosquatting”.)