Finance and Risk over the Long Run

Risk is a consequence of almost all human activity, and societies developed a number of strategies to deal with it, falling in one of three categories: avoid, pool and share. Avoidance is frequently inefficient because of the opportunity costs of shunting risky activities. Early on, individuals and organisations devised forms of pooling risks together or of sharing risk among them. Finance provided many techniques for this.

Risk Pooling

Risk can be pooled by self-insurance. Medieval traders used to split their cargoes in different ships, the same way that investors today diversify their portfolios.Medieval traders used to split their cargoes in different ships, the same way that investors today diversify their portfolios. Pooling can also be done by insurers. While individual risks are idiosyncratic, aggregate risk is more manageable. Early forms of life insurance were tried in the Middle Ages, but the business only matured once actuarial life tables appeared in the late 18th century. Increasingly accurate estimates of death risk by age and the law of large numbers allowed life insurance companies to match a predictable stream of payments with the regular income from insurance premia and their investments.

North Commercial wharf of Charleston, S.C. with cotton bales for shipping to foreign and domestic ports via sailing ships. 1878

North Commercial wharf of Charleston, S.C. with cotton bales for shipping to foreign and domestic ports via sailing ships. 1878Insurers expanded their range of products over time by offering protection for less predictable risks, such as property damage, fire, natural disasters, or even financial losses. Because these risks were harder to forecast, insurers increasingly found themselves exposed to “tail risk”, whereby the concentration of simultaneous claims exceeded the insurer’s funds. Fire insurance companies, for instance, were first introduced after the 1666 Great Fire of London but faced high bankruptcy rates given the scale of the damage provoked by large city fires such as those started by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Consequently, re-insurance emerged in the 19th century to deal with the fallout of these rare events.

Risk Sharing

Risk-sharing techniques developed parallel to insurance. Their specificity lies in spreading risk among several investors, rather than concentrating it on a single insurer. Since Roman times, traders could insure their cargo and even the ship carrying it by selling bottomry bonds, which they only had to repay if the ship reached its destination. Sharing was also a solution to cover large risks that exceeded the capacity of a single insurer. Insurance brokers shopped around for potential investors, who added their names to the policy, thereby “underwriting” it. The rise of stock exchanges since the 17th century also created a liquid market for transferable securities (securitisation) that allowed issuers to sell and distribute risk. Pfandbriefe (covered bonds), collateralised by mortgages, were introduced in Germany in the late 18th century. Trading in government bonds also created a market for political risk, which investors can follow from the daily spreads of sovereign bonds.CAT bonds are mostly sold by re-insurers to protect themselves against the losses from natural disasters such as earthquakes or hurricanes. In return, investors are paid very high yields

Good ideas bear repeating, and many of these solutions were rediscovered in the financialisation wave since the 1970s. Mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) became infamous in the 2008 financial crisis, while today’s sovereign debt market is as active as its 19th century predecessor. Even bottomry bonds were revived with the introduction of “catastrophe bonds” (CAT) in 1997.

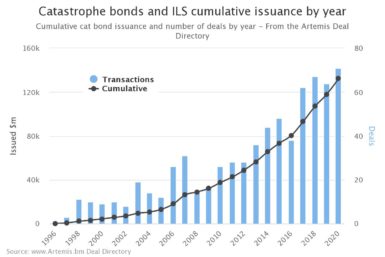

FIGURE 1 | CATASTROPHE BONDS AND ILS CUMULATIVE ISSUANCE BY YEAR, showing the quick growth of the CAT bond and insurance-linked securities (ILS) market since its inception.

FIGURE 1 | CATASTROPHE BONDS AND ILS CUMULATIVE ISSUANCE BY YEAR, showing the quick growth of the CAT bond and insurance-linked securities (ILS) market since its inception.Investors in these bonds stand to lose their capital if a given “act of God” is triggered. CAT bonds are mostly sold by re-insurers to protect themselves against the losses from natural disasters such as earthquakes or hurricanes. In return, investors are paid very high yields which are not correlated with other financial assets. An attractive proposition in any time (but especially in the world of rock-bottom yields since 2008), investment in these products increased from USD 22 billion in 2007 to over USD 100 billion today.

Pandemic Bonds

In 2003 Swiss Re introduced the first pandemic CAT bond insuring against spikes in mortality rates in five advanced nations. In 2017 the World Bank issued its own pandemic bond to pre-finance aid to developing nations in case of a pandemic. The bond’s interest varied between 7 and 11.5 percent above LIBOR (paid by Germany and Japan) and attracted a lot of interest. However, in April 2020 this was the first pandemic bond to be triggered by the COVID crisis. Though the amount lost by investors was but a fraction of the aid committed by the Bank since COVID (USD 200 million against USD 160 billion), the event chilled the market. COVID reminded investors that pandemic risk is in fact correlated with financial markets and the World Bank dropped the idea of issuing new pandemic bonds.

As insurers and markets extend their cover against increasingly hard-to-predict events, they face new obstacles. In their recent book Radical Uncertainty, John Kay and Mervyn King warn against the false precision we get from statistical models of risk, based on probabilistic assessments about all possible states of the world. Black swan events such as the 2008 crisis are very hard to predict, but in real life we are not even certain about all kinds of possible events. In other words, life is not a game of roulette with clear fixed rules and probabilities. Unlike risk, uncertainty is not easily quantifiable and cannot be insured or traded efficiently in markets.Unlike risk, uncertainty is not easily quantifiable and cannot be insured or traded efficiently in markets MBSs and CAT bonds exemplify the limits of the financialisation of risk. Rather than hoping that probabilistic models will fill our knowledge gap about “unknown unknowns”, the authors call for more resilient strategies to prepare for future uncertainty and more flexible and collaborative decision-making to deal with it. COVID exposed the fragile networks of trade and finance underlying our globalised world and the need for international cooperation to fight the pandemic. This is to date the strongest endorsement of resilience and cooperation.

PODCAST | The Unlikely Hierarchy of Health Risk – Ryan Whitacre

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | La globalisation des diversités – Fabrizio Sabelli

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | AI, Big Data, and Big Risk? Michael Kende

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | The Fabrication of Terrorism Risk – Andrea Bianchi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.