Understanding Global Environmental and Health Risks in the 21st Century

There is some risk in characterising global environmental change and its consequences as “global risks”. A risk is a danger that has not yet materialised. When it is “global”, its effects may be perceived as someone else’s problem. Above all, “risks” may be demobilising. Those who are to blame for climate change, ozone depletion, ocean pollution or biodiversity loss know it well. After losing the public relations battle around the drivers of the problem, their next demobilising strategy is to pretend that “nothing can be done about it”.

For global environmental change, these difficulties are compounded by the genuine complexity of the causal and feedback processes involved. For example, there is a clear but complex relation between environmental degradation and the COVID-19 pandemic, embodied in processes such as (1) land use change that modifies the boundaries between wildlife and human populations, (2) illicit wildlife trade, which facilitates the smuggling of sometimes highly regulated wildlife specimens (e.g. pangolins), (3) global air and maritime transportation, which disseminate pathogens, and (4) basic air pollution, which may serve as a vector for contamination or of vulnerability in a population affected by a respiratory disease. Knowledge of complexity can be both empowering and demobilising. Thus, we know that there is a link between global environmental change and global health security, but at such an aggregate level, it is unclear what to do next. Knowledge of complexity can be both empowering and demobilising.

Zooming Out

Our inability to deal with global environmental change comes in part from the habit of thinking in small specialised boxes instead of adopting a more holistic approach. To understand why “zooming out”, rather than “zooming in”, may be important we can recall an observation made by Alfred Lotka, a prominent biophysicist of the early 20th century: “The physical laws governing evolution in all probability take on a simpler form when referred to the system as a whole than to any portion thereof. It is not so much the organism or the species that evolves, but the entire system, species and environment. The two are inseparable.”

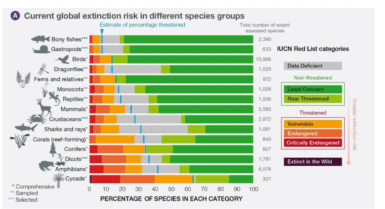

FIGURE 1 | CURRENT GLOBAL EXTINCTION RISK IN DIFFERENT SPECIES GROUPS

FIGURE 1 | CURRENT GLOBAL EXTINCTION RISK IN DIFFERENT SPECIES GROUPSThis broad view was at the time shared by many other thinkers. In his book The Biosphere (1926), Vladimir Vernadsky called attention to the “bio-geo-chemical” cycles that govern the Earth system. The idea of Gaia conceptualised by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis (1974), and more recently that of Paul Crutzen’s Anthropocene (2002) with its “planetary boundaries” (2009), have similarly conveyed the importance of adopting a macrolevel approach to geological integration. Considering bio-geo-chemical cycles highlights the role of life in sustaining, but also in undermining, the conditions in which life unfolds. These and other aggregate categories such as “climate change” or “biodiversity loss” involve considerable levels of ontological construction and therefore ambiguity. Yet, the realisation of their complexity must be a stepping-stone for action, not demobilisation.

Knowledge Integration and Multiscale Approach

What is then to be done? From an academic perspective, two basic suggestions seem apposite. First, to capture such intricate phenomena, broad conceptual aggregations are necessary, which depend upon the set-up of conducive institutional structures. Seeing the world in “disciplines”, institutionalised in faculties, departments, degrees, courses, textbooks, professions, etc., seems increasingly inadequate to tackle such challenges. What is needed is more problem- (not discipline-) driven thinking, encouraged by and institutionalised in problem-driven structures. “Environment” schools are currently leading this trend, as previously did public policy, public health, business schools and, even earlier, faculties of medicine.

Second, describing phenomena at different scales, highlighting their interconnections, is absolutely fundamental for knowledge to be mobilising.Describing phenomena at different scales, highlighting their interconnections, is absolutely fundamental for knowledge to be mobilising. Highly individualised occurrences, such as a person playing cards with friends in Northern Italy who gets sick and dies, may result from complex aggregate phenomena unfolding at the global scale. The vanguard in this scale integration effort lies, perhaps, in a new generation of (non-equilibrium) integrated assessment models, which connect the local and the global. One prominent example is the modelling of “tipping points” in the dynamics of global environmental change. To understand it, a detour is useful. Social scientists tend to assume that climate policy works like heating water into vapour and then cooling it back to water: putting more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere may change the dynamics of the climate system, but removing them is sufficient for the climate to go back to its prior “equilibrium”. Politically, this means “pollute now and clean up later”. Yet, this representation of the world is demobilising and inaccurate. Emitting greenhouse gases should be compared to burning a piece of paper. Once the paper turns into ashes – the tipping point – one cannot simply go back by cooling the ashes. There is no “pollute now, clean up later”, for either climate change or other examples of global environmental change.

The 21st century will be increasingly confronted with global environmental change felt not just at the aggregate human timescale, but also in our everyday experience as individuals. Knowledge integration and appropriate levels of description are key conditions for us not to be mere spectators of a “risk” we can indeed address.

PODCAST | The Unlikely Hierarchy of Health Risk – Ryan Whitacre

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | La globalisation des diversités – Fabrizio Sabelli

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | AI, Big Data, and Big Risk? Michael Kende

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | The Fabrication of Terrorism Risk – Andrea Bianchi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.