Risky Entanglements between States and Online Platforms

Every two years, the data generated in the world is doubling. The number of connected devices is projected to reach a staggering 29.3 billion by 2023. Although these numbers hide substantial variation between highly connected nations and others, the datafication of human life is a global phenomenon that imposes a high level of transparency on individuals, while allowing online platforms to develop and use sophisticated microtargeting techniques in complete opacity. In this context, new risks arise on a global scale, putting into question the role and ability of the state to protect its citizens and institutions.

Opaque filters and lack of data protection

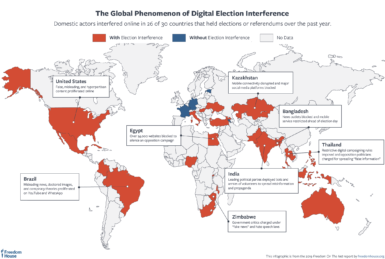

FIGURE 1 | THE GLOBAL PHENOMENON OF DIGITAL ELECTION INTERFERENCE

FIGURE 1 | THE GLOBAL PHENOMENON OF DIGITAL ELECTION INTERFERENCEIn the past two decades online platforms have accumulated vast amounts of personal data. Consumer data is collected from numerous sources (e.g. online behaviour) and across devices (e.g. smartphone) thanks to behavioural tracking (e.g. cookies). Citizens have agreed, most of the time unknowingly, to exchange their personal data and metadata (i.e. data about data such as device used or location) for “free” services (e.g. web referencing, instant messaging). By aggregating and correlating data from these numerous sources, online platforms have gained the capacity to identify and profile citizens with great precision across devices, time and space. This new psychographic profiling capacity has raised ethical and governance concerns among experts and populations. In this context, the European Commission asked online platforms to increase their efforts to moderate content more effectively. Moreover, the European Union (EU) adopted new legislation to ensure a better protection of privacy (i.e. the General Data Protection Regulation).

FIGURE 2 | THE CHINA MODEL OF INTERNET CONTROL

FIGURE 2 | THE CHINA MODEL OF INTERNET CONTROLHowever, protecting privacy and moderating content to prevent the spread of disinformation and fake news contradicts the business model of online platforms, which is based on unrestricted access to personal data and user attention.

The data collected feeds the machine-learning algorithms of online platforms designed to tailor relevant content to each online user. The gatekeeping role of online platforms is magnified by the sheer size of content available digitally. PageRank, for instance, is Google’s algorithm ranking websites according to specific user profiles and concurring keywords. However, by filtering only “relevant” content these algorithms fail to confront users to alternative views and risk confining them to sterile echo chambers. Moreover, how “relevance” is defined by online platforms remains opaque and the evolving nature of algorithms continues to elude regulators. In other words, the criteria used to select the information citizens access online are not transparent, challenging the capacity of the state to protect its citizens and institutions.

An Ambiguous Relationship between Governments and Platforms

Governments, on their part, have an ambiguous relationship with online platforms. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the necessity of collaborating with platforms to collect data and track citizens. However, such collaboration is not new. Political candidates have rapidly adopted online platforms to reach out to potential voters. Governments have mobilised online platforms to pursue economic goals, e.g. boosting foreign direct investment or tourism through digital campaigns, or for the sake of “security”, e.g. monitoring and watching their populations or interfering in the domestic affairs of foreign countries.

New techniques increase the precision, scope and scale of persuasion, while reducing their accountability. Psychometric profiling, for instance, makes ads more persuasive by adjusting them to specific psychological traits. Dark posts – disappearing after viewing – allow political actors to show transient messages to the most influenceable Facebook users. The Cambridge Analytica scandal shed light on the risks intrinsic to these new data-driven advertising techniques and their manipulative potential, notably with regards to voting behaviour.

Intelligence agencies have used online platforms to access personal information through backdoors. In cases such as the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in Donbass, online platforms have been misused or instrumentalised for military purposes, to weaken the adversary, instil chaos, and support kinetic military forces. In parallel, liberal democracies, including the EU, collaborate with online platforms to combat disinformation campaigns through the adoption of new policies, fact-checking tools, and awareness campaigns.The relationship between states and online platforms presents a major risk for the populations and the legitimacy of national and, indirectly, international public institutions.

The relationship between states and online platforms presents a major risk for the populations and the legitimacy of national and, indirectly, international public institutions. States are struggling to find adequate mechanisms to regulate and tax the tech multinationals. Their difficulty is representative of the crucial and yet ambiguous role that platforms play today. On the one hand, states must ensure the protection of their citizens, including their privacy and free access to plural sources of information. On the other hand, states depend more and more on these digital infrastructures to communicate with their citizens and perform certain sovereign tasks. By giving such an important role to the private interests running the online platforms, states are jeopardising not only the credibility of their efforts to ensure the protection of their citizens, but also their future legitimacy.

PODCAST | The Unlikely Hierarchy of Health Risk – Ryan Whitacre

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | La globalisation des diversités – Fabrizio Sabelli

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | AI, Big Data, and Big Risk? Michael Kende

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.

PODCAST | The Fabrication of Terrorism Risk – Andrea Bianchi

Research Office, The Graduate Institute, Geneva.