Naypyidaw, Myanmar: A Capital Devoid of Protests

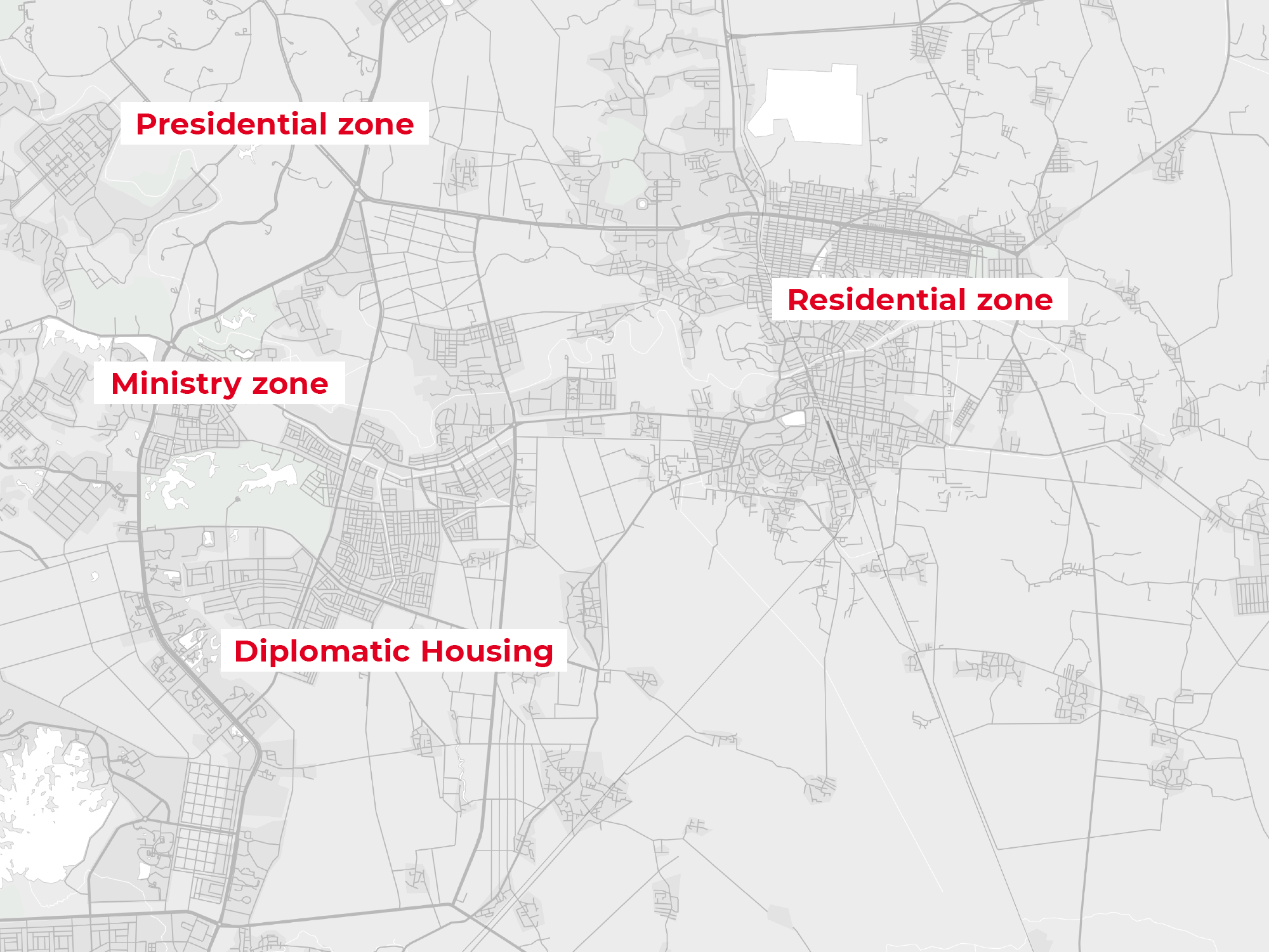

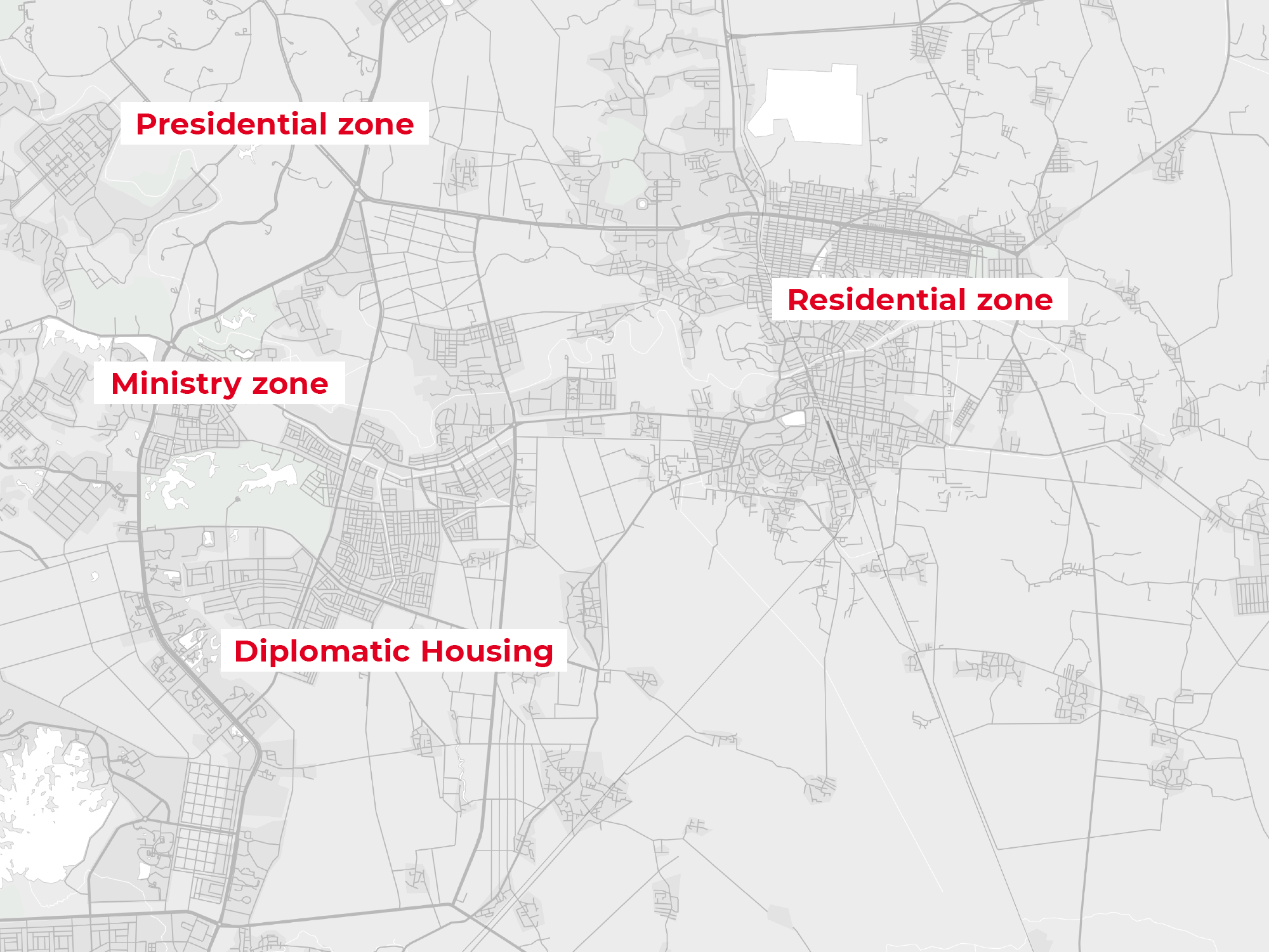

Figure 1 – Naypyidaw lacks a clearly defined ‘city centre

Today, we observe a renewed interest in the theme of decolonisation in three interrelated fields: in the academic world which opens new areas of research and teaching (e.g. decolonisation studies; decolonising the curriculum), in the practice of professionals and international actors who are revisiting their way of working, as well as in the vocabulary and activism of civil society targeting the remnants of colonial times such as street names, statues or museum objects. The renewed focus on decolonisation brings forth underlying issues such as the lingering of Eurocentrism, continued oppression of indigenous people, cultural relativism, the ongoing materiality of colonialism, the guilt of the West or, more generally, “the darker side of Western modernity”. While decolonisation has had a lasting impact on the political scene (with the decolonisation movements of the 1960s) and theoretically in the realm of academia, it lags behind in practice as processes, mentalities and epistemes are still permeated by “coloniality”. The present issue puts therefore decolonisation into historical perspective and provides fresh analytical perspectives on its epistemologies and methodologies as well as its practical application and consequences in various fields.

This issue has been coproduced by the Graduate Institute’s Department of International History and Politics and the Research Office. It also includes contributions from other research centres and departments of the Institute.

We currently face a baffling paradox. While since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 a seemingly inexorable process of globalisation has been foreshadowing a peaceful and frontierless world, the number of walls across the world has been rising at a steady pace. Liberal and open societies buttressed by trade, international law and technological progress were supposed to implacably contribute to the erosion of frontiers and walls between nations. However, in a context of surging populist discourses, securitarian anxieties and identitarian politics as well as concomitant flows of migration alimented by climate change, conflict and poverty, nations have recently started to barricade themselves behind new walls.

The present Dossier takes stock of the current state of the multilateral system and its future prospects. It aims to explore to what extent global governance is in crisis as the global geopolitical order is undergoing fundamental shifts and liberal universalism is losing traction. It assesses potential of reform in extant institutions as well as emerging trends, tools and forums that are reshaping multilateral practice on a daily basis.

Note – The dossier was drafted before the Covid-19 world crisis.