Naypyidaw, Myanmar: A Capital Devoid of Protests

Why Naypyidaw is so “special” in terms of social protests ? For the author, the reason can be found in its urban layout, designed precisely to counter potential forms of popular dissent.

Violence In the City

Existing literature suggests that conflict is becoming more and more urban. Höglund, Melander et al. (2016), for instance, show that “the occurrence of violence in urban areas is almost triple that of violence in a rural area” (p. 66). Even forms of political demonstration, according to Calluzzo (2009), are becoming increasingly urbanised.

In Myanmar, this phenomenon is both urban and rural: protest locations have ranged from its biggest city—the 1988 Uprising and the 2007 Saffron Revolution in Yangon—to the less populated settlements of the rural Kayin State. However, unlike the rest of the country, Myanmar’s recently built capital, Naypyidaw, has experienced relatively few episodes of protest. Even following the coup d’état in 2021, popular discontent was expressed mostly in the former capital of Yangon. In Naypyidaw, according to some residents interviewed by Frontier Myanmar, people “live their lives as if politics doesn’t matter . . . Naypyidaw is silent of fighting and protests” (“Nothing is Good” 2022). Why is it that Myanmar’s capital—a city of more than a million inhabitants—remains “quiet” in the midst of widespread political upheaval and transformation?

The Symbolic Significance of Sites of Protest

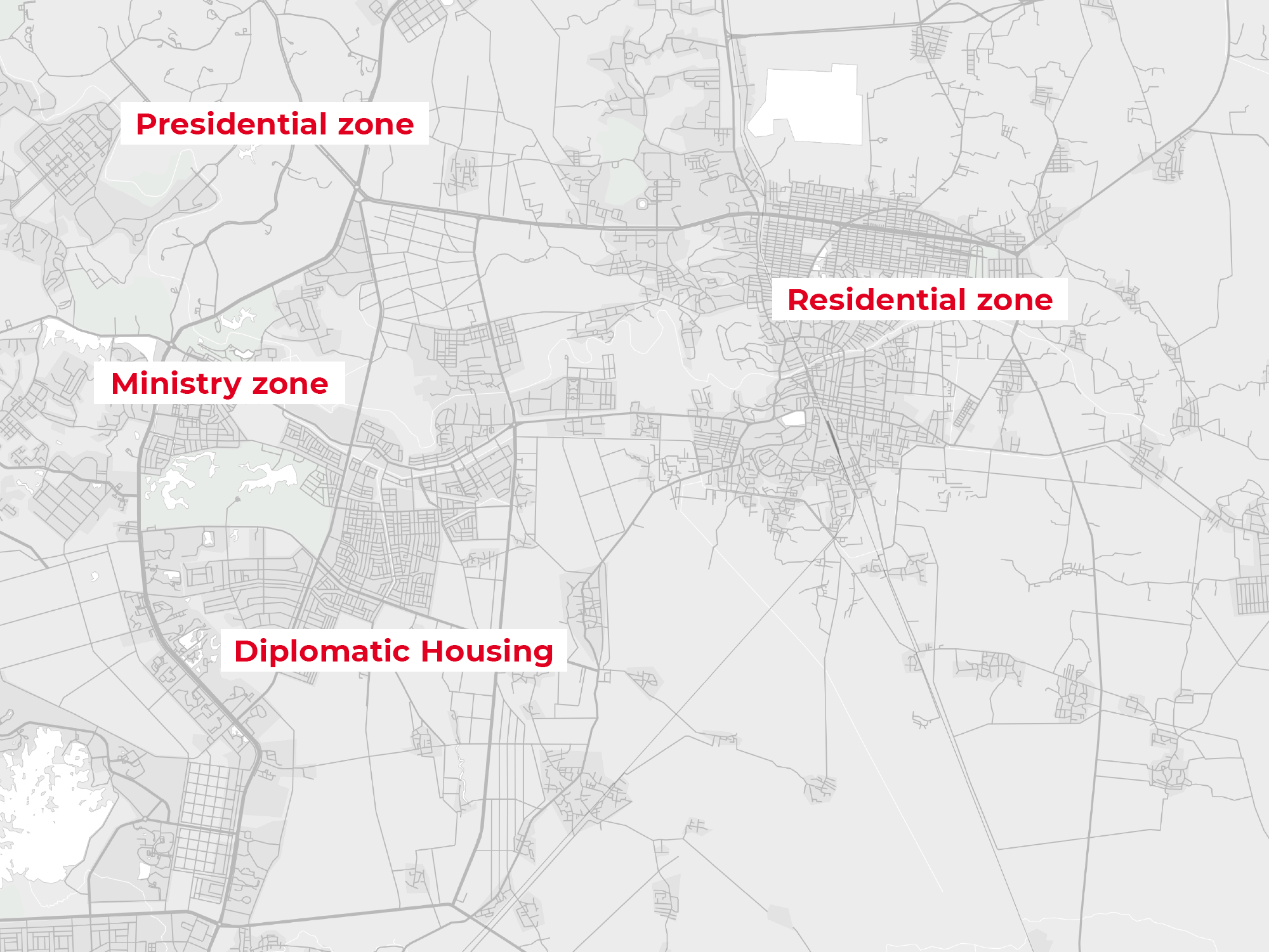

As shown in figure 1, Naypyidaw lacks a clearly defined “city centre”. Most of the population lives in dwellings that have been described as “slums” (Kusch 2011), which used to be part of the old town of Pyinmana, subsequently incorporated into the Naypyidaw Union Territory. Most new development occurred west of Pyinmana in meticulously delineated areas, such as the diplomatic, ministry and presidential zones.

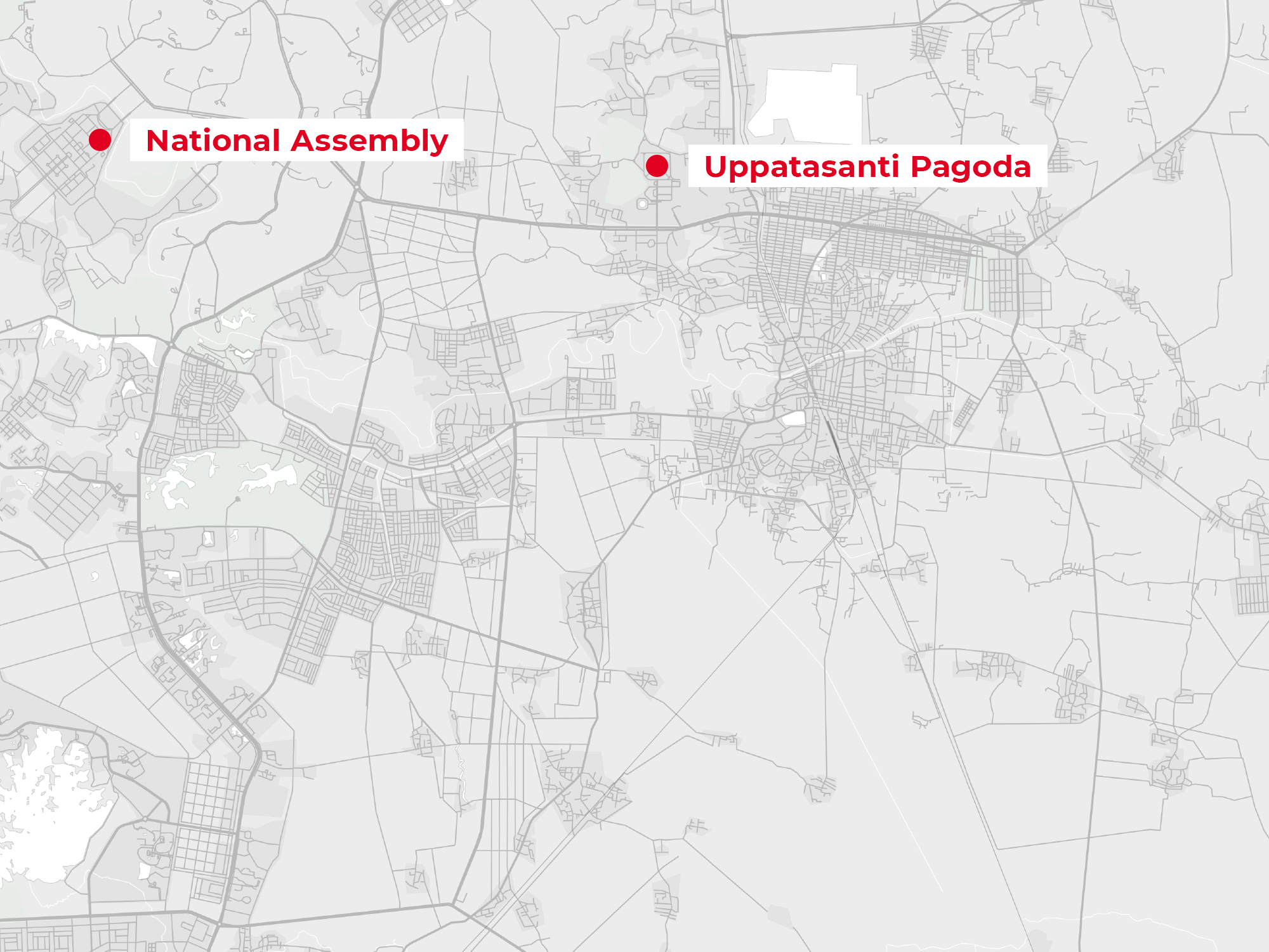

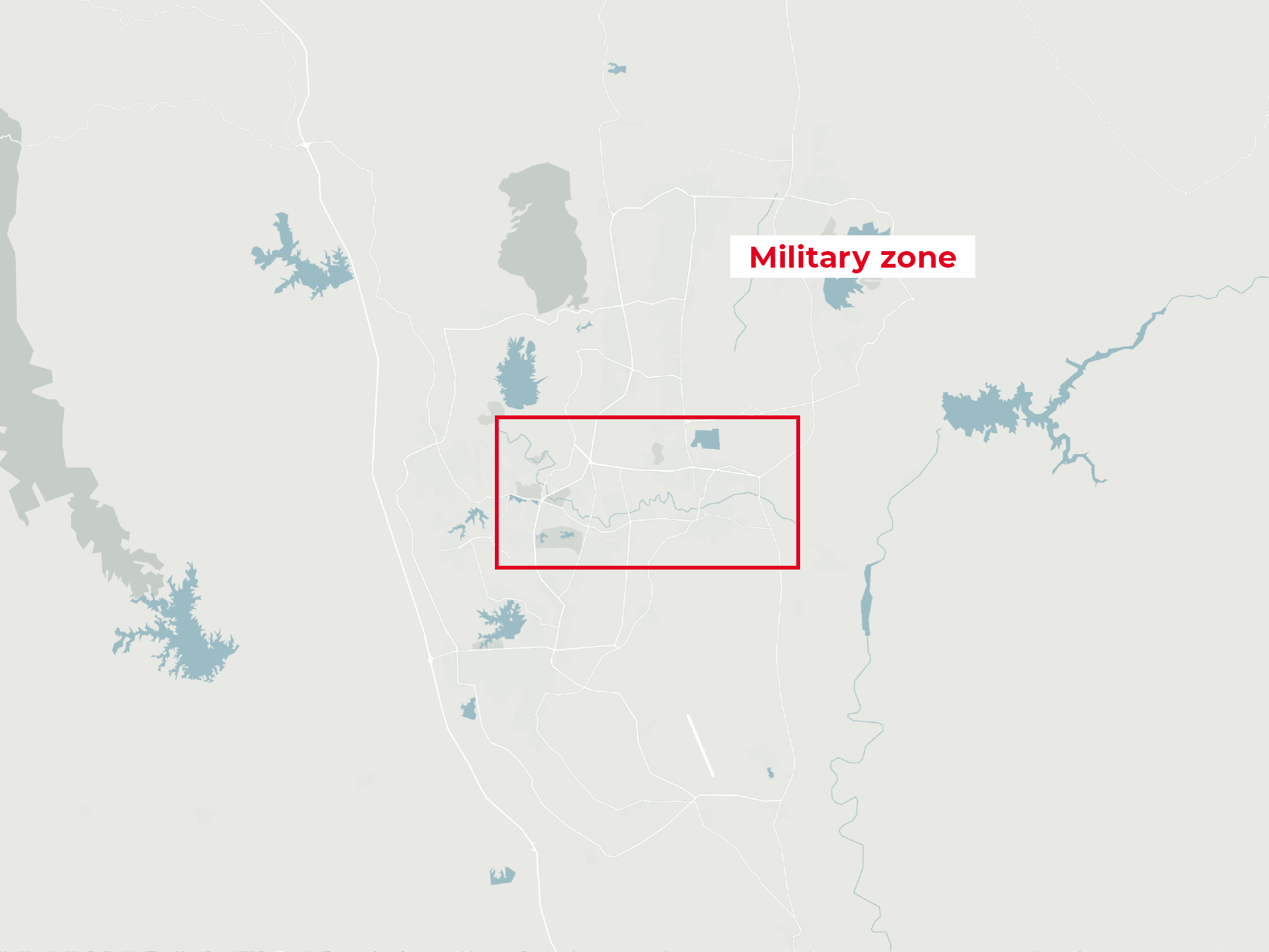

From satellite imagery of the city, I identified two places where popular discontent may be expressed: the Uppatasanti Pagoda and the National Assembly (cf. fig. 2). Both sites are located on the Yazahtarni Road, where isolated arrests of demonstrators were made as they tried to use the road to reach the rest of Naypyidaw from Pyinmana (‘Five Engineers Among Dozens’ 2021). Gül, Dee & Cünük (2014), in their analysis of Istanbul’s Taksim Square protests, argue a place’s symbolic value turns it into a gathering site for protesters. This can also be seen from Kazakhstan’s 2022 Qandy qañtar, which saw a large group of people overtake Almaty’s Republic Square and set fire to the key buildings representing the country’s political power. Both the Uppatasanti Pagoda and the National Assembly hold symbolic significance, as the former, a place of worship, is the city’s most recognisable monument and an exact replica of the Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon’s symbol, while the latter, situated in the presidential zone, is the physical embodiment of the nation’s government. Since Myanmar’s government is ruled by the military, one may reasonably assume that the military zone would serve as a target for civil disobedience. However, this area is particularly inaccessible as it is quite far from the centre of population—around 20 km (cf. figure 3).

Urban Morphology as a Form of Anti-Protest Measure

By examining the successful 2011 Friday of Anger in Tahrir Square, and the violently repressed 2013 pro-Morsi sit-ins in Rabaa Al-Adawiya Square, Mohamed, Van Nes & Salheen (2015) conclude that an elevated number of intersections and ‘short urban blocks’ (p. 14) can aid the quick retreat of a crowd, while at the same time hindering the movement of the police. A lack of accessibility, on the other hand, confines protesters, turning them into vulnerable targets. The outcome can be further shaped against their odds with increased road width and reduced street density.

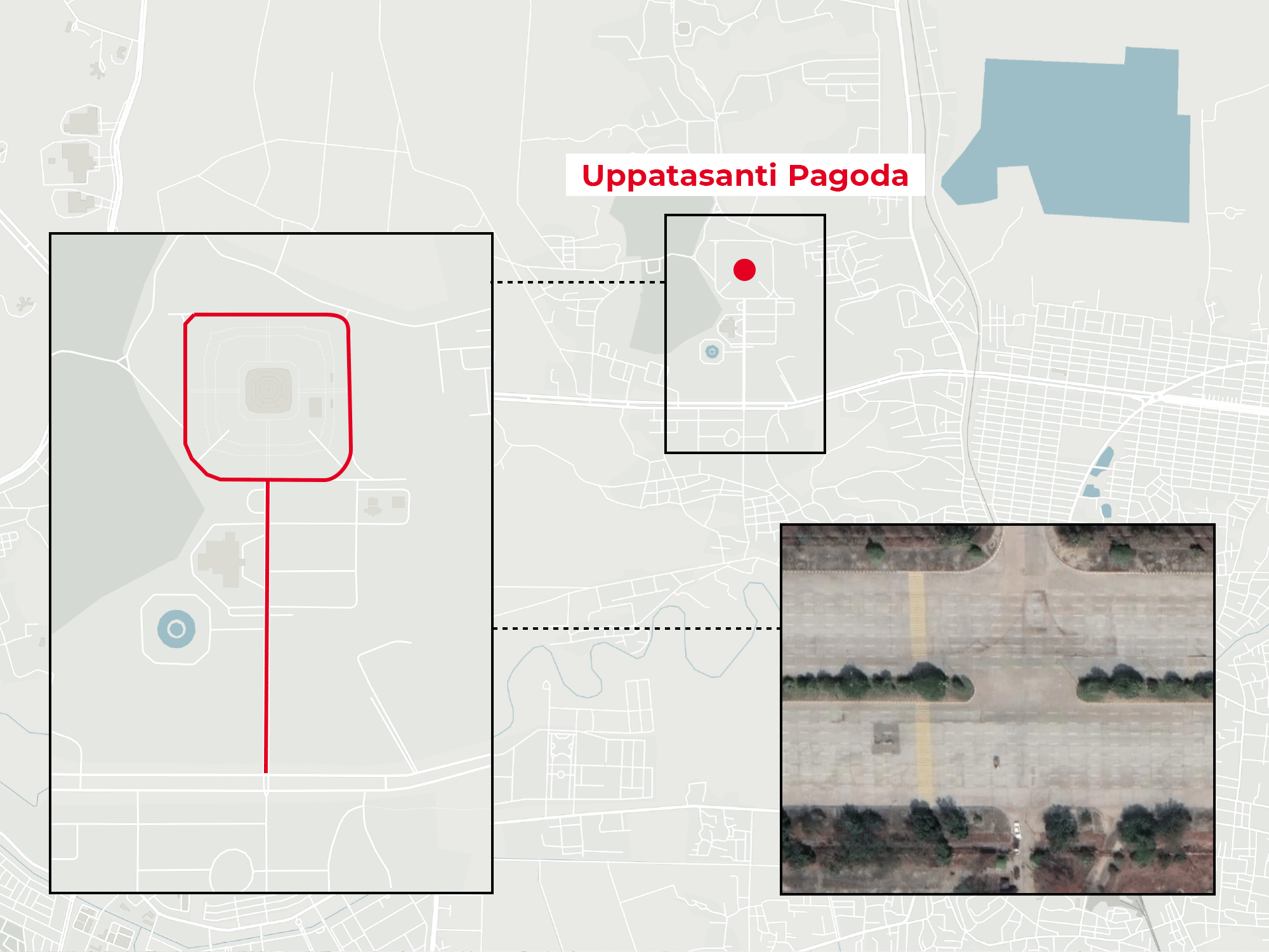

As figure 4 shows, the lack of accessibility of the Uppatasanti Pagoda makes it especially difficult for protesters to flee from the police or military. The monument can only be reached via one straight road: the nodes and narrow alleyways that guaranteed the success of the Tahrir Square protest are nowhere to be seen. Even Rabaa Al-Adawiya, where an extremely brutal crackdown on civilian protests took place, has more intersections than the area surrounding the Uppatasanti Pagoda. A potential flow of people can only be forced into one direction along a linear path. The street then opens into a the wide Yazahtarni Road, which, with its 10 lanes on each side, is 80 m across. Such a large space would make a sizeable group of protesters appear insignificant, turning it into an easy target for the police.

As depicted in figure 5, the National Assembly has two entrances, both protected by gates. The three roads on the southern side lead into the government officials’ housing zone, which is similar to a gated community. Thus, the entrance on the northern side is the only one close enough to the government’s buildings for a potential protest to take place. Other than the sheer distance from the centre of the population (11 km), the 10-lane boulevard leading to it ends abruptly shortly after the National Assembly, with barriers and police posts on the north-western side. As with Uppatasanti Pagoda, there is only one way in which the flow of protesters can be redirected, and here, for even longer distances. For this reason, the National Assembly presents more obstacles as a potential assembly point for Burmese protesters.

Segregation to Control the Population

When looking at Cape Town, Madaleno (1997) argues that “city management and planning are political acts” (p. 178). The segregation of Cape Town followed the logic of the Roman divide et impera rule, which enabled the white minority to maintain distance from and, at the same time, to rule over the other ethnic groups of South Africa. The author also mentions that this separation can be enacted along racial and/or status lines (p. 178). Naypyidaw evidences its own approach to segregation in an effort to better control its inhabitants and to prevent them from gathering and expressing dissent. According to Staniland (2010), urban insurgencies are a type of “high-risk collective action”, made possible by “robust community structures that generate identification and mobilisation” (p. 1268). Relegating the city’s inhabitants to their own spaces hinders the formation and mobilisation of "robust community structures" across the city. As a result, "high-risk collective action" remains unlikely when concrete steps are taken to eliminate circulation and collective identification.

Added to this, Naypyidaw’s urban structure separates its inhabitants from government workers, who reside in gated communities, inaccessible to the rest of the city’s population. Their homes are separated from the rest of the city by both sheer distance and police-monitored gates. Security, order and ease of traceability are internal to the gated areas as well, with the roofs of the houses being colour-coded in a way that renders the workers’ ministries easily identifiable (see fig. 6)—blue roofs, for instance, are used to identify the homes of personnel from the Ministry of Health, as evidenced by Seekins (2011, p. 4).

Conclusion

A spatial analysis of Naypyidaw reveals how urban design was used to prevent and control any form of large-scale gathering aimed at expressing popular dissent. The two sites of protest, selected for their symbolic significance, showcase design choices made to deter the congregation of large crowds. Segregation serves as yet another method of control, making it impossible for city-wide collective action to happen. Together, these features suggest that Naypyidaw was purposively designed to minimise protest and maximise control. It follows that the spatiality of the urban environment, as in the case of Naypyidaw, effectively eliminates the need for authoritarian governments to resort to the use of force to counter protests.

Figure 1 – Naypyidaw lacks a clearly defined ‘city centre

Figure 2 – In Naypyidaw, the Uppatasanti Pagoda and the National Assembly are the two places where popular discontent may be expressed

Figure 3 – The military zone is far from the centre of Naypyidaw, and thus escapes the protests of the population

Figure 4 – The location of the Uppasanti Pagoda makes it difficult for protesters to escape from the police

Figure 5 – The National Assembly has two entrances protected by doors

Figure 6 – The roofs of the houses are colour coded for easy identification