Making Peace with Urban Political Settlements

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-1ym6-5q93A GLOBAL PRACTICE OF URBANISING PEACEMAKING?

Peacemakers have traditionally favoured comprehensive peace agreements as the gold standard for resolving conflict—a state-centric practice, with nationwide peace agreements being the most common (Badanjak 2022). Yet, contemporary conflicts are increasingly enmeshed in a “diversity of causes, actors, and intensity of violence”, complicating both the dynamics of conflict and accompanying solutions for peace (Contemporary Conflict 2018). With cities featuring ever more prominently in conflict, the need to find creative solutions beyond the traditional comprehensive peace agreements is all the more pressing (Wennmann 2021; MacLeod et al. 2016, Chapter 2; Buchhold et al. 2018).

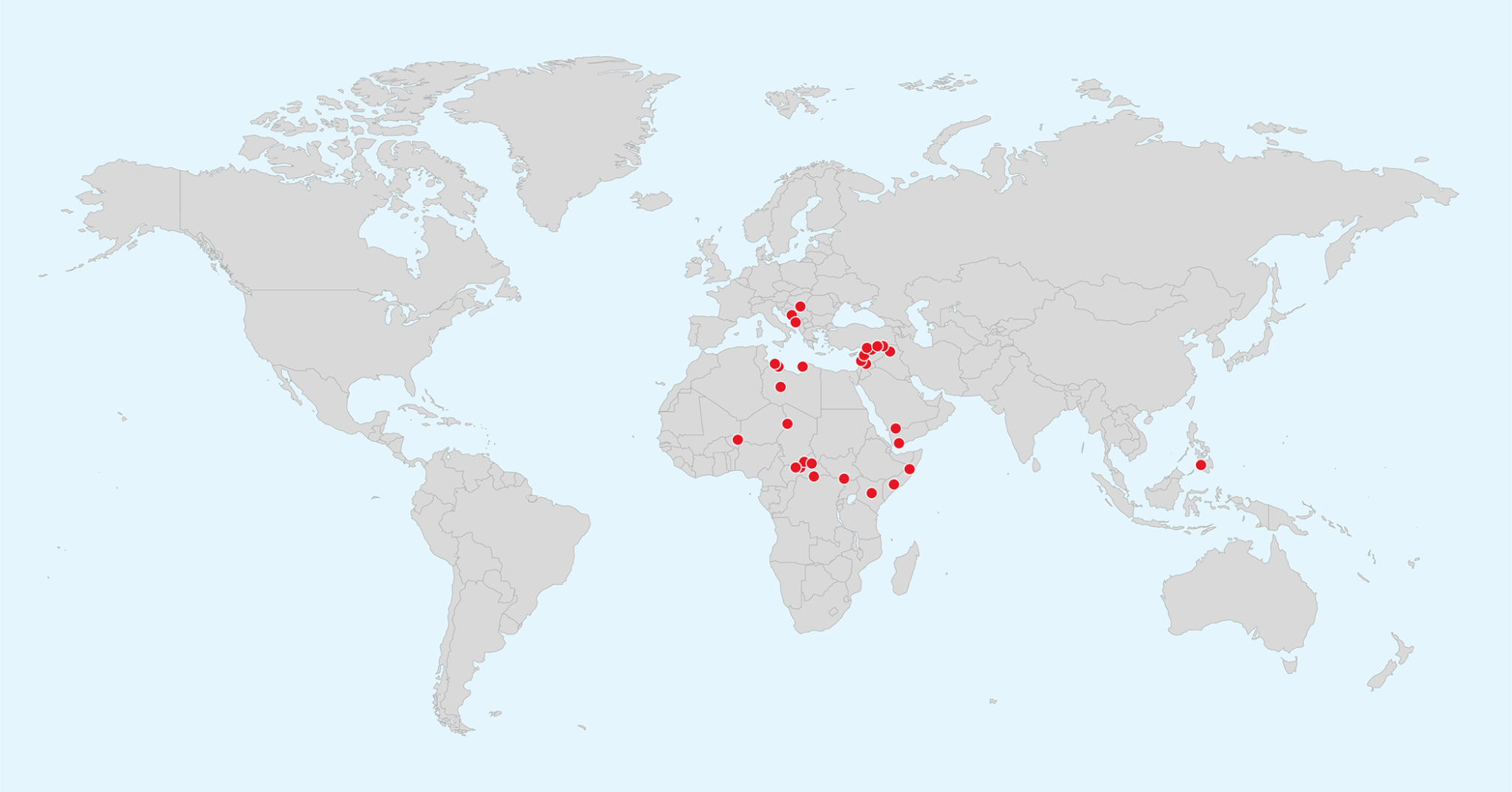

Conflict actors and urban populations must constantly adapt to the changing nature of conflict within cities. During “particular shifts or ruptures”, as for example, a change in the composition of the dominant coalition governing a city, urban populations face new outbursts of violence that require political settlements to be renegotiated (Goodfellow 2018, p. 219). In situations such as these, urban peace settlements are better positioned to adapt to changes in actor composition and restore order amid renewed violence. The result has been an expansion of urban peace agreements—some forty urban peace agreements signed since 1990, with a peak in 2018 (Figure 2)—ceasefires being the most prominent type of settlement (Figure 2).

THE LENS OF THE URBAN POLITICAL SETTLEMENT

Coined by Mushtaq Khan, urban political settlements establish political order and end conflict, albeit, contingent to political actors’ ability to “overthrow or seriously disrupt the settlement” (Kelsall 2018, p. 662). The heart of UPS concerns how actors distribute control and rents from governing institutions. Opportunities for rent-seeking vary, and in conflict economies, violence is an effective means to extract rent (Eaton et al. 2019).

As such, control over urban areas is key, and often reflective of one’s potential share of revenue (Ibrahim et al. 2022; Idler & Tkacova 2020; Voller 2022). Conflict economies de-escalate when peace dividends are realised, yet, this de-escalation is often precarious (Bell 2018) as power configurations can shift and result in divisions that are less amenable to agreement over the division of spoils. Much of the work of UPS, then, lies in institutionalising power and control in an effort to establish and maintain political order (Khan 2010, p. 20). In this regard, UPS may be constituted as dynamic, stakeholder-driven solutions to conflict that differ meaningfully from more static, top-down peace-making efforts.

URBAN POLITICAL SETTLEMENTS IN SYRIA

With Syrian cities most heavily targeted during the conflict, UPS served as an alternative to create order amid violence in non-government-controlled areas. For over a decade, parties to the conflict negotiated settlements (Hinnebusch & Imady 2017; Michiels & Kizilkaya 2022), some 17 in total, all but one involving the state and a non-state armed actor (NSAAs) (Bell et al. 2020).Urban political settlements establish political orders based on access to institutions and economic rents, creating peace dividends. In north-western Syria, 16 UPS were negotiated between non-state armed actors, twelve of these agreements being ceasefires, with only the Qamshilo Agreement of 2016 involving the Syrian government. The Idlib, Aleppo, and Al-Hasakah, the governorates that experienced the most violence, all signed UPS (Abdullah 2022).

In Dara’a, ceasefires provided opportunities for non-state actors to alter the governance system and influence “the trajectory of local institutions”. Since 2017, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) governed large parts of north-western Syria. Despite high levels of violence and economic deterioration, the SSG provided local populations with services and other public goods (iMMAP 2022; Prasad 2022) and opportunities for rent seeking (Mehchy et al. 2020, pp. 17–19). In Idlib, engagements between the SSG and competing NSAAs led to the consolidation of order (Drevon & Haenni 2020; Tsurkov 2022). As the political body of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the SSG’s engagement with local councils has effectively increased popular representation, resulting in greater stability. That said, these UPS were by no means uniform. For one, parties to UPS varied, with local civilian actors and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham being the most represented (see Table 1). In addition, the type or stage of agreement reached also varied, with ceasefires being the most prominent. De-escalation is a process whereby actors create economic power-sharing agreements. Finally, the outcomes of UPS also varied to include both an escalation and de-escalation of violence. Saraqib and Khan Sheikhoun saw more fatalities after the UPS than before, while in al-Bab the result was reversed. Whereas the first two cases saw violence instigated by actors not included into the UPS, there was no change in the composition of actors in al-Bab.

The dynamic nature of contemporary conflict calls for a more pragmatic approach towards peace-making initiatives. An exploration of urban political settlements in Syria suggest that UPS can create political order between coalitions, albeit contingent on peace dividends that more effectively distribute power and rents. As armed conflict increasingly takes place among multiple actors in urban spaces, UPS constitute a viable alternative to peace-making and conflict-resolution—one that is more adaptable to changes in group composition and resulting shifts in power; a bottom-up, problem-driven approach. In Syria, ceasefires were the most prominent outcome of UPS, albeit with different levels of success. What is clear is that multiple, non-state armed groups served as the key brokers of urban peace settlements, rather than traditional state actors such as the Syrian government. As such, UPS, though volatile and subject to disruption, have the potential to provide a creative entry point for peace-making in fragile, urban contexts.

Electronic reference

Berutti, Emilian. “Making Peace with Urban Political Settlements.” Global Challenges, Special Issue no. 2, March 2023. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/special_2/making-peace-with-urban-political-settlements. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-1ym6-5q93.The editors of this issue are grateful to Gopalan Balachandran, Christiana Parreira, Michelle Weitzel, and the editorial team at the Geneva Graduate Institute for comments on the essays.

Table 1: Urban Peace Agreements in Syria, 2011-2022

Agreement between Tahrir al-Sham and the elders of the village of Hazano

Signatories: Local civilian actors and HTS

Agreement type: Partial substantial framework

Fatalities 1: 32

Fatalities 2: No data has been found

Agreement between Tahrir al-Sham and Sarmin Shura Council on the raid on the outskirts in the city

Signatories: Local civilian actors and HTS

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: NA

Fatalities 2: NA

Saraqib Agreement

Signatories: Local civilian actors and HTS

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: 5

Fatalities 2: 35

Agreement between the Local and Shura Coucils and Jabat Tahrir al-Suriyyah, Tahrir al-Sham and Faylaq al-Sham regarding the village of Kfar Darian, Idlib

Signatories: Local civilian actors, HTS, Failaq al-Sham, and Jabhat Tahrir Suria

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: NA

Fatalities 2: NA

Statement issued by the Sheikhoun Shura Council on the handover of Sheikhoun city

Signatories: Local civilian actor

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: 7

Fatalities 2: 14

Agreement between Ahrar al-Sham, Desert Sector (AAS), and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Northern Desert Sector (HTS), on Tel Touqan.

Signatories: Local civilian actors, HTS and AS

Agreement type: Pre-negotiation process

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: 11

al-Bab Security Agreement

Signatories: Local military and civilian actors, Sham Front, Al-Sultan Murat, Sham Legion, Ahrar al-Sharqiyyah, Al-Muntasir Bi-llah, Firqa al-Hamza, Al-Firqa al-Shumaliyyah, Suqur al-Shimal, Brigade 51, Northern Brigade, Al-Sultan Muhammad Fatih, AS

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: 272

Fatalities 2: 73

Agreement between Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and Free Idlib Army

Signatories: HTS and Free Idlib Army

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: 0

Agreement between Ahrar al-Sham (AAS) and Jabhat Fatah al-Sham (JFS) signed by al-Jawlani and al-Hamawi

Signatories: AS and JFS

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: 37

Cessation of Hostilities between Jund al-Aqsa and Ahrar al-Sham (AAS) in Kansafra

Signatories: Jund al-Aqsa, AS, The Mountain Hawks Brigade, JFS

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: 0

Statement by Jabhat Fatah al-Sham on Ceasefire in Kansafra

Signatories: Local civilian actor, JFS and Dawah Council

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: 0

Minutes of Agreement (between Ahrar al-Sham (AAS) and Jaysh al-Fatah, Idlib)

Signatories: Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya and Jund al-Aqsa

Agreement type: Pre-negotiation process

Fatalities 1: NA

Fatalities 2: NA

Agreement between Ahrar al-Sham (AAS) and Farqa 13

Signatories: Jabhat al-Nusra and Al-Farqa 13

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: NA

Fatalities 2:NA

Qamishlo Agreement

Signatories: Rojava administration and the Syrian government

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: 13

Untitled Agreement [between al-Nusra Front and Free Syrian Army, Mara al-Hurma, Idlib]

Signatories: Jabhat Al Nusrah and the Free Syrian Army

Agreement type: Partial substantial framework

Fatalities 1: NA

Fatalities 2: NA

Untitled Agreement [between Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant and Northern Storm Brigade]

Signatories: Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant and Northern Storm Front

Agreement type: Ceasefire

Fatalities 1: NA

Fatalities 2: NA

Field Agreement between the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and People’s Defence Units (YPG) in the city of Ras al-Ain (Serê Kaniyê)

Signatories: The Free Syrian Army (FSA) and People’s Defence Units (YPG)

Agreement type: Substantive comprehensive framework

Fatalities 1: No data has been found

Fatalities 2: No data has been found

Source: Bell et al., 2020; Raleigh et al., 2010

Figure 1. – Spatial Analysis of Global Urban Peace Agreements, 1990-2022

Source: Bell et al., 2020

Figure 2. – Urban Peace Agreements by Stage, 2011-2021.

Source: (Bell et al., 2020)