Hybrid Political Orders in Urban Settings

Public goods and services provision has long been considered a mode to enhance state legitimacy and “central to the existence of the state” (OECD 2010, Mcloughlin 2019).

In contrast to state-centred notions of public goods provision, scholars have explored how armed non-state actors effectively occupy this role, engaging in governance-like activities ranging from basic service provision to the formation of elaborate bureaucratic structures (Arjona 2017). Between the two extremes, lie hybrid political orders where “diverse and competing authority structures—sets of rules, logics of order, and claims to power—co-exist, overlap, and intertwine, combining elements of introduced Western models of governance” and modes of “governance” by non-state actors (Boege et al. 2009, p. 17). This essay examines urban manifestations of hybrid governance through discussing Hezbollah’s ‘governance-like’ activities in Beirut’s al-Dahiyeh neighbourhood. I argue Hezbollah mobilises political legitimacy and resources within traditional political arenas to enhance the effectiveness of its non-state governance structures and demonstrate the utility of Hezbollah’s notion of resistance as a principle around which to organise society.

The Hybrid Political Order of Al-Dahiyeh

Rather than acting solely as a political party or armed actor, Hezbollah has used the organisation’s existence as a hybrid state and non-state actor to benefit both aspects of the organisation’s existence. Hezbollah uses political participation and access to state structures to support its non-state governance and promote Shia needs while also using the state’s weak presence to justify the existence of Hezbollah’s non-state institutions (Al Sayyad 2011). While Hezbollah maintains status as a Lebanese political actor, the group uses its resistance-centred identity and non-state roots to distance itself from state failures and mobilise disdain for the state amongst its electoral base. In this manner, Hezbollah’s hybrid status allows it to acquire standing as a state-legitimised authority without bearing responsibility for state failures.

State-Based Legitimacy

Hezbollah’s establishment of a hybrid political order in al-Dahiyeh is closely linked to the neighbourhood’s ‘marginalised identity.’ Hezbollah formed its al-Dahiyeh social organisations in response to a centralisation of Shia sentiments of marginalisation in al-Dahiyeh during the Lebanese Civil War. With roots in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, Hezbollah gained influence in the Baalbek area, Southern Lebanon, and al-Dahiyeh during the war. Underrepresented in the post-mandate confessional system, the Lebanese Shia community was politically marginalised before the war. In the 1960s, migration resulted in an influx of Shia migrants from southern Lebanon to al-Dahiyeh, which gained a reputation as poor and degraded (Harb 2010). During the war, government service provision in al-Dahiyeh deteriorated while Shia immigration increased. Thus, al-Dahiyeh gained a reputation as a Shia marginalised periphery (Sajan 2011). Acting on Shia sentiments of marginalisation, Hezbollah acted as a pillar for Shia political mobilisation and established a web of neighbourhood service organisations. While the Shia community was removed from pre-Taif Agreement patronage networks, Hezbollah’s al-Dahiyeh service provision provided the organisation with the political support to mobilise state resources for Shia interests.

Though Hezbollah initially spurned the Lebanese state project, instead advocating for Islamic governance, following the civil war, Hezbollah strayed from calls to replace the Lebanese state and participated in Lebanese politics. Hezbollah has legitimised its Dahiyeh influence through continued municipal election victories. First participating in municipal elections in 1998, Hezbollah won sizeable victories in the municipalities constituting al-Dahiyeh. Hezbollah built on subsequent municipal election victories in al-Dahiyeh by using its social influence in the area to push mayors to work with Hezbollah security and service institutions (Chatham House 2021). Municipal authority is a key link between state resources and Hezbollah organisations; Hezbollah formed the Union of Municipalities of Beirut Southern Suburbs which uses municipality-pooled assistance to support Hezbollah’s service organisations (Chatham House 2021; Marei 2020). Under the union, Hezbollah operates al-Dahiyeh’s police force and integrates Hezbollah’s Indibat force (Marei 2020).

Resistance Society

Hezbollah’s municipality-level electoral success in al-Dahiyeh municipalities has provided a state-legitimated territorialization of Hezbollah control. Yet, through Hezbollah’s insistence on producing a “resistance society” the organisation has aimed to produce an organisational alternative to the state. Building on Shia beliefs of the communal nature of resistance, Hezbollah’s production of a resistance society expands the concept of resistance beyond combat and into the social sphere by focusing on resistance to exclusion, social injustice, and occupation (Harb & Leenders 2005). Hezbollah uses political participation and access to state structures to support its non-state governance and promote Shia needs Hezbollah’s construction of a resistance society plays on perceptions of Lebanese Shia marginalisation and aims to instil a sense of Shia-centred solidarity in al-Dahiyeh (Abboud 2016). It’s Manifesto highlights the importance of resistance in its ideology stating, “first is the path of resistance and opposition, a growing movement that thrives on military victories, political successes, an established model both at the popular and political levels” (Alagha 2011, pp. 116-17). Building on the ideological importance of “resistance”, Hezbollah has aimed to form a web of institutions in al-Dahiyeh embedded in an intertwined religious and political framework and centred around forming Dahiyeh’s Shi’a residents into a “society of resistance” (Harb 2005, pp. 174-75). In keeping with this rationale, Hezbollah’s Deputy Secretary-General stated that “resistance is a societal vision in all its dimensions. It is military, cultural, political, and media resistance. It is the resistance of the people and the mujahideen, the resistance of the ruler and the nation” (Naim 2008). By inscribing the organisation’s social service provision with resistance-focused values, Hezbollah has sought to provide alternatives to unreliable state services and create a resistance-centred communal solidarity in al-Dahiyeh. Hezbollah’s social welfare provision in Dahiyeh began with support to militant families fighting Israel but evolved to include public social services, including educational, microcredit, and health services (Harb 2010).

Hezbollah officials stated, “The Resistance needs a rear support base, behind the front lines. … It is unreasonable to think that a Resistance formed of armed groups can succeed if cut off from its society. … It is the rear where all forms of support, cultural, social, educational, and political support combine” (Naim 2008). According to the organisation’s general director, Hezbollah’s urban improvement body “Jihad al-Binaa” has provided utility and reconstruction services in post-war al-Dahiyeh with the goal of building Dahiyeh into a resistance society able to endure conflict while also “keeping pace with people’s daily and living needs” (Shreim 2022). While Hezbollah’s cooptation of state resources supports its non-state institutions, Hezbollah’s focus on differentiating its service provision from the state through references to a “resistance society” offers al-Dahiyeh a communal alternative to a state-linked identity and allows Hezbollah to distance from state failures.

Conclusion

Rather than operating only in the state or non-state sphere, Hezbollah has utilised its political status and resistance-focused ideology to create a hybrid political order and build support in al-Dahiyeh. Capitalising on the marginalisation of Lebanon’s Shia population and Lebanese political sectarianism, Hezbollah has leveraged state resources to support non-state services while distancing from Lebanese state failures.

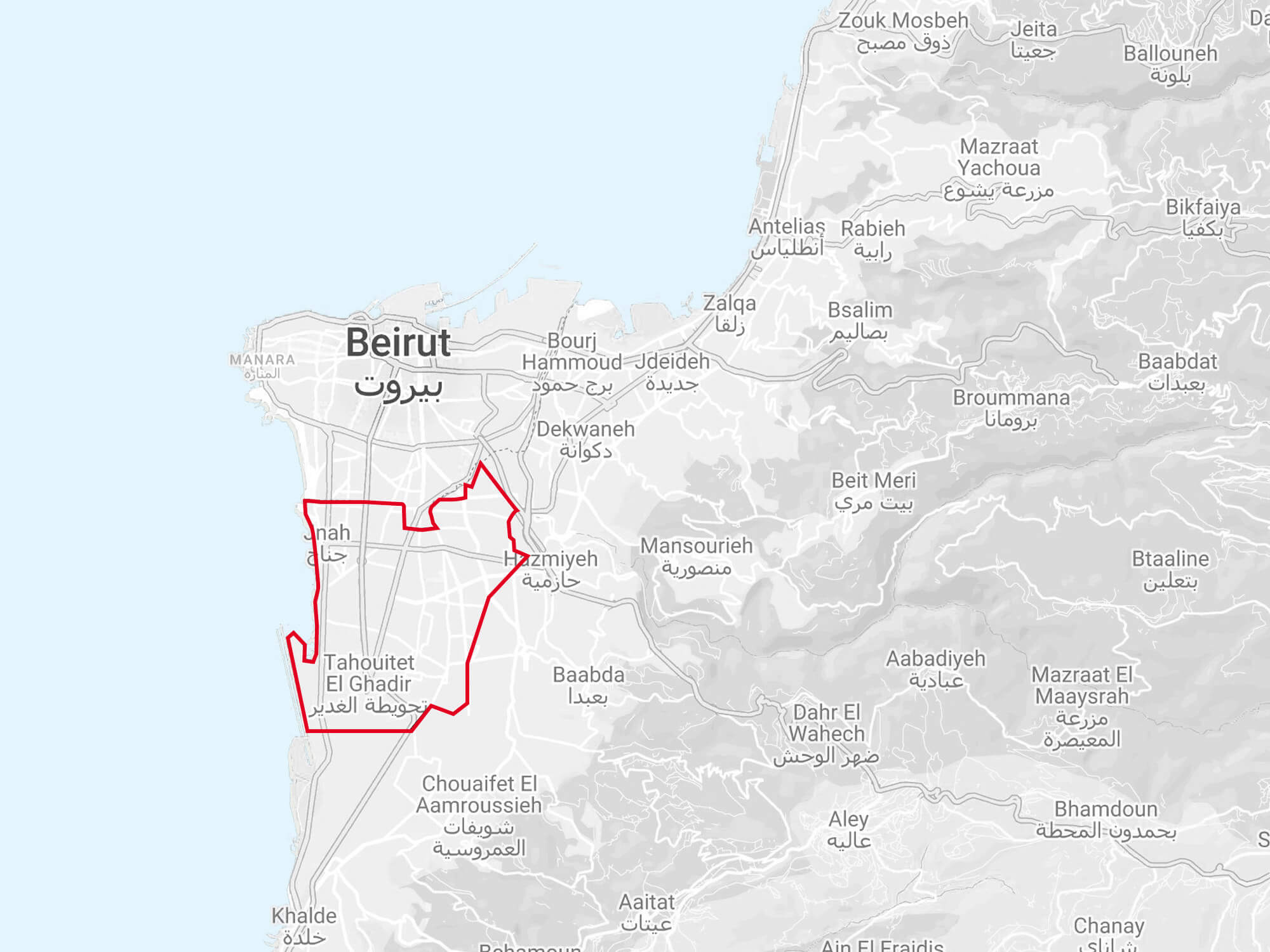

Map: Al-Dahiyeh in Relation to the Greater-Beirut Area

Based on Google map, by YPC.