Planetary Conflict: Exploring the Urban Geography of Boko Haram

Boko Haram is often characterised as a largely rural insurgency based in forests with a tendency to displace villagers (Mordi 2022, p. 186). At its strongest point, in 2014, it controlled a territory of over 20 local governments and 1.7 million people in Northeastern Nigeria (Mahmoud 2018, p. 106). Yet, scholars of urban conflict appear to have ignored the movement entirely, despite its urban roots, mobilisation, and targets.

Planetary Conflict

Conflict researchers often define insurgencies as either rural or urban based on where rebellion is concentrated (Staniland 2010, p. 1624). Given a propensity of rebels to camp in the hinterlands, where the state is less present and powerful (Kalyvas 2006, pp. 132–33), insurgencies are typically categorised as rural (Staniland 2010, pp. 1627-28). It follows that urban insurgencies, being too limited in number to enable generalisation, have not featured prominently in comparative research (Staniland 2010, pp. 1627–28).

In a related but somewhat different vein, recent work by urban scholars has introduced the notion of planetary urbanisation—effectively blurring the distinction between urban and rural (Roy 2009; Brenner & Schmidt 2011; Merrifield 2013; Katsikis 2014). According to Brenner (2013) “the geographies of (capitalist) urbanisation are necessarily global insofar as (a) cities are connected to one another across the entire world economy, and (b) they consume the resources of widely dispersed territories, which are in turn massively operationalised as their linkages to cities intensify.” Planetary urbanisation effectively moves away from the urban/rural divide by conceptualising urbanisation not as the concentration of population within a territorial space, but rather, as “processes both within and beyond those settlement spaces that are demarcated as cities” (Brenner & Schmid 2014, p. 749).“In 2014, Boko Haram overtook ISIL as the most deadly terrorist threat in the world with 6,644 deaths attributed to it.” — Global Terrorism Index 2015, p. 2

To import the notion of planetary urbanisation into the realm of conflict studies, I introduce the notion of planetary conflict. Planetary conflict considers how conflicts are linked across vast geographies of urbanisation, occurring through the “…relentless production and transformation of socio-spatial organisation across scales and territories” (Brenner & Schmidt 2011, p. 13), opening new imaginaries of where and how we might study urban conflict. Researchers are invited to step back and frame the urban not by the juridical limits of a city but by the spatiotemporal fluidity of actors across more traditionally demarcated urban and rural divides. Planetary conflict offers a theoretical lens to explore the urban geography of Boko Haram, despite its ostensibly rural base. It illuminates how the violence of Boko Haram has been produced in, across and between urban centres in Northeastern Nigeria. Whereas Boko Haram is a well-studied movement, its urban morphology has not received due attention.

The Urban Geography of Boko Haram

Urban Formations

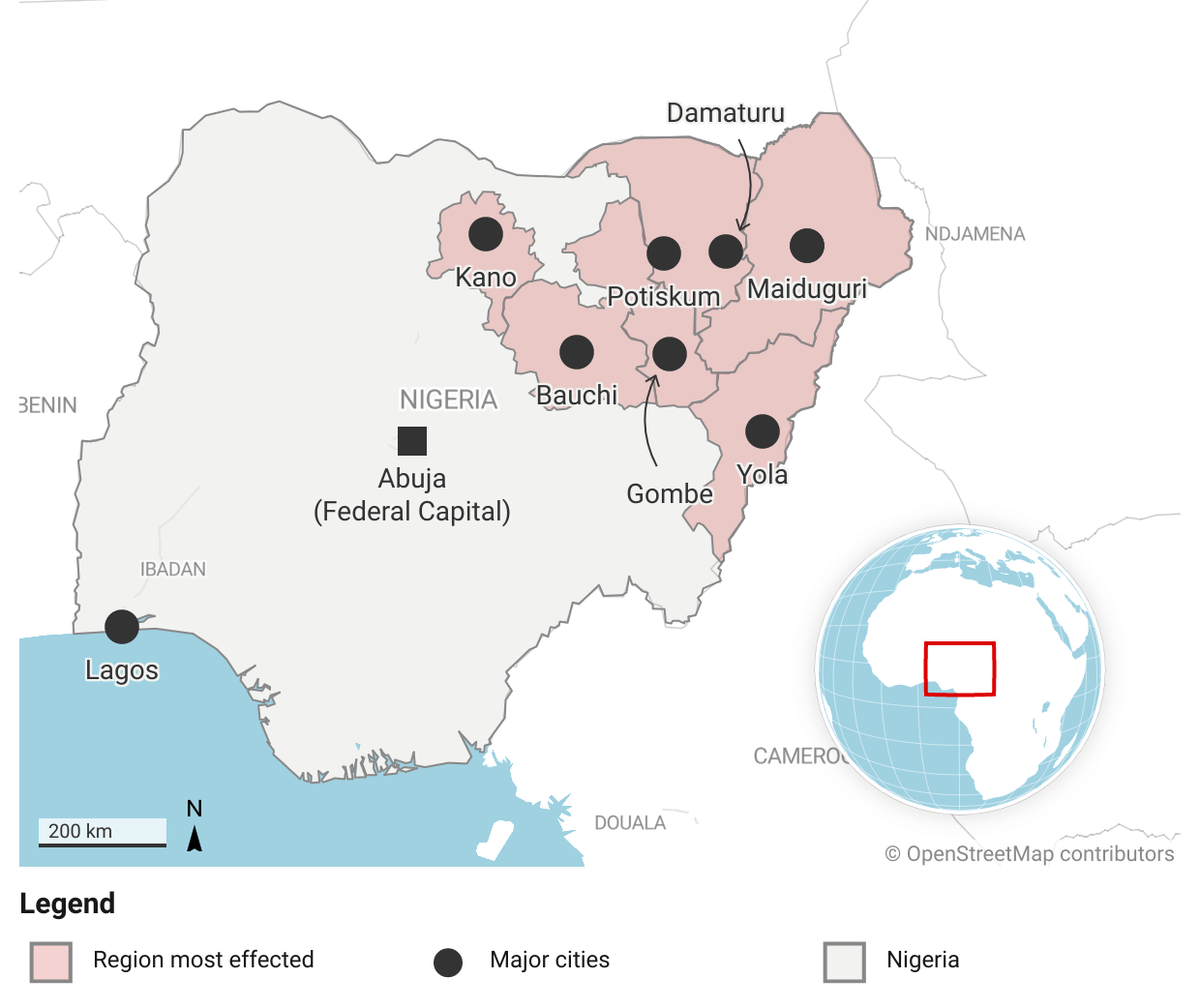

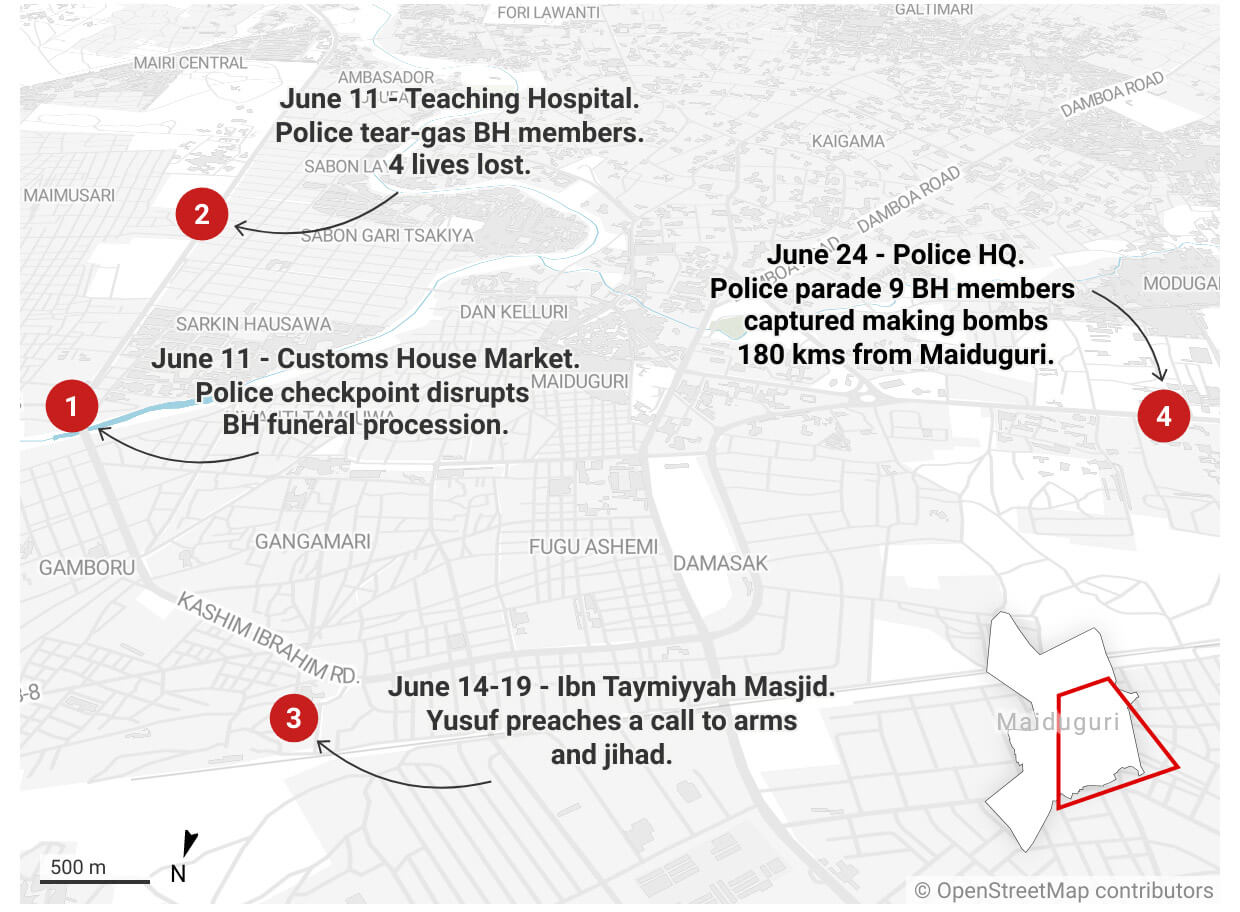

Boko Haram originated in Maiduguri, the largest city in Northeastern Nigeria. With a census population of nearly 750,000 in 2006, Maiduguri has long been a hub of West African commerce and Islamic scholarship. Maiduguri shaped the founder of Boko Haram, Muhammad Yusuf, as well as his closest followers who would go on to lead the movement. The contested urban religious environment in Maiduguri helped mold Yusuf’s ideology and identity in relation to more mainstream Islamic leaders (Umar 2012, p. 140) . In 2003, he was expelled from the Ndimi mosque due to his anti-boko positions. Yusuf then used his family’s wealth and networks to amass political currency and local support (Omeni 2020). He erected his own mosque on his father-in-law’s land with financing from a former State Commissioner for Religious Affairs, and initiated a massive recruitment drive from Maiduguri, attracting members across the Northeast (Omeni 2020, pp. 21-22; Adibe 2013, p. 11). The urban environment resulted in more violent and frequent interactions with state security forces. The violence that lit the match occurred in 2009 when members of the Nigerian military repeatedly targeted Yusuf’s followers at checkpoints in Maiduguri (Nwankpa 2018, pp. 47–48). Map 2 shows where this took place and how it triggered a series of events that led to the explosion of the first Boko Haram bomb.

Urban Structures

Boko Haram rapidly spread to other major urban centres around Maiduguri. Urban linkages across a vast geography helped Yusuf build a network of over 500,000 followers (Adibe 2013, p. 11). Over a span of a few short years, Yusuf managed to accumulate considerable ‘soft power’ through not only his religious activities but by providing services that increased his followers’ reliance on him, including schools, a hospital, microfinance and a newspaper (Omeni 2020). He also built up an entire social caste of ‘Okada drivers’ (motorcycle taxis) in Northeast Nigeria through his micro-financing activities. These activities contributed income and expensive jeeps that compounded Yusuf’s influence (Adibe 2013, p. 11; Omeni 2020, p. 22). The regional urban fabric therefore lent shape to Boko Haram’s ideology and enabled it to spread. Memories of the historical Kanem-Bornu empire, whose territory spread across Northeastern Nigeria, Cameroon and Chad (Barkindo 2016) with Maiduguri as its capital, were precisely what Yusuf had in mind (Zenn & Pieri 2018, p. 279).The regional urban fabric therefore lent shape to Boko Haram’s ideology and enabled it to spread

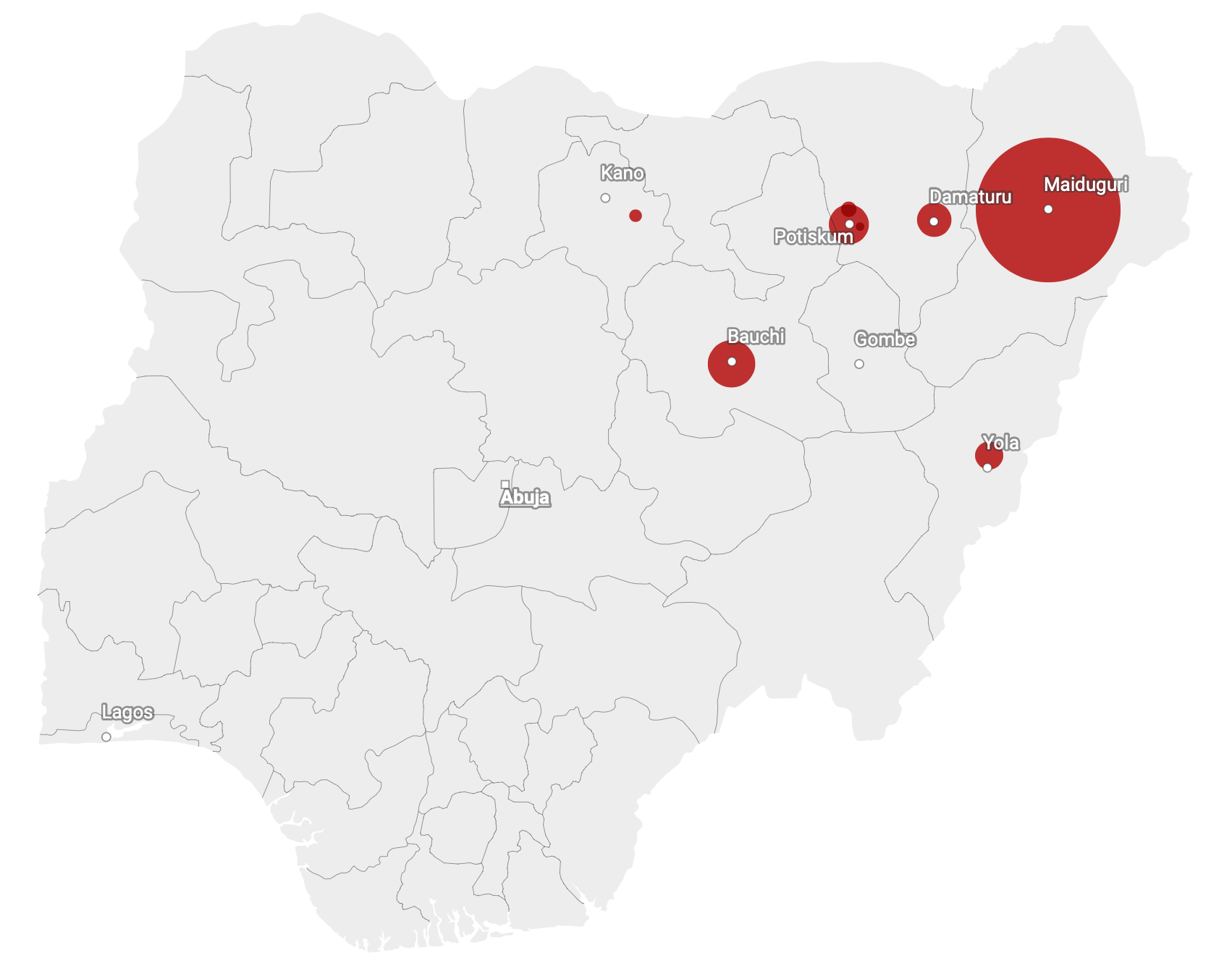

Boko Haram leveraged its power in Maiduguri to build an urban structure of networked cells across the Northeast (McQuaid & Asfura-Heim 2015, p. 8). This network enabled Boko Haram to launch a coordinated uprising across six states in the Northeast. In just four days, an estimated 800 lives were lost—virtually all in cities (see map 3). The deployment of security forces to urban centres in the region to counter Boko Haram, in turn, forced the movement to reconstitute its centre of gravity in the countryside (Matfess 2017).

Urban Extensions

Armed conflict is sustained by the flows of resources and people into, within and between cities. The infrastructure that transports resources into cities also extends into the hinterlands and has played a central role in the Boko Haram conflict. For example, Campbell (2020) writes: “Boko Haram has increased attacks on the road from Maiduguri to Kano, the only remaining safe highway of the six major roads that connect Maiduguri with the rest of the state and country.” A week prior to Campbell (2020)’s writing, insurgents had blown up electricity infrastructure around Maiduguri. Telecommunication infrastructure has also been a consistent target with 150 base stations reportedly damaged by Boko Haram in 2012 alone (Onuoha 2013).

Beyond war with the Nigerian state, Boko Haram is waging jihad on the urban infrastructures between cities, in other words, urban ‘extensions’ into the non-urban. Map four illustrates how Boko Haram’s attacks from 2010-2015 converged on major highways linking urban centres in the Northeast. 50 secular schools, which may be conceptualised as extensions of planetary urban values and knowledge into a traditionally agrarian and Islamic stronghold, were also attacked (Human Rights Watch n.d.).

Similar attacks on urban extensions underpin the diffusion of Boko Haram’s insurgency to other parts of Nigeria. The Ansaru faction, which split from Boko Haram, is suspected to have played a role in bombing the Kaduna airport and multiple bombings of train tracks on the newly constructed Abuja-Kaduna railroad (Zenn 2022).

Conclusion

A planetary conflict lens sheds light on aspects of the Boko Haram movement that other studies neglect. In particular, it highlights the urban roots of an ostensibly rural insurgency and maps its spread between cities and into the hinterlands, targeting infrastructure within the rural-urban divide. Conceptualising conflict through the lens of planetary urbanisation expands the reach and relevance of both urban and rural conflict. Many insurgencies categorised as rural move into urban centres, with the reverse also holding true. In fragile contexts characterised by high inequality and structural violence (Degila 2020), insurgents move fluidly within and between urban geographies as a strategy to increase their impact, challenge the state apparatus and sustain their movement. This fluidity and its implications have been overlooked in conflict studies, where the rural-urban divide more often takes precedence.

From 2010-2015, violence involving Boko Haram was concentrated along major highways that link urban centers.

Map 1 – Boko Haram in Northeastern Nigeria

Region where Boko Haram has been most active.

Boko Haram defined as including factions SWAP, JAS and Ansaru. They have been active in other parts of Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon.

Map: Adam Talsma • Created with Datawrapper

Map 2 – Violence Escalates in Maiduguri: June 11 – 24, 2009

On June 24 the first Boko Haram bomb inadvertently exploded in the home of a member in Maiduguri. Here are the key events leading up to this and where they occurred in the urban center of Maiduguri.

Map: Adam Talsma • Source: Collated from Murtada 2013, Zen 2020, Omen 2020 and media sources. • Created with Datawrapper

Map 3 – Violence Spreads Across Urban Centers: July 26-30, 2009

From July 26 – 30, 2009, violence involving Boo Haram spread across urban centers in the Northeast. The location of the red circles in this map show where this violence occurred and the size indicates the relative share of the estimated 800 fatalities that resulted.

Map: Adam Talsma • Source: Collated from ACLED, UCD and media reports. • Created with Datawrapper