Italian Hospitality

Research has focused on the spatial dimensions of forced migration rather than the temporal ones (Dotsey & Lumley-Sapanski 2021). Space and time, however, are instrumentalized to govern transient subjects, creating spatio-temporal borders that can be defined as the product of urban apportionment, i.e., the discriminatory processes by which space and time are delineated and diminished when seeking urban asylum (Hall et al. 2022). Housing plays a crucial role in the journey of transient subjects. All the more so in urban spaces, where the location of housing dictates the capacity of transient subjects to claim their rights and live full lives. If misplaced within a city, these spatio-temporal borders riddle their lives with uncertainty and isolation. This essay examines how Italy’s reception system interacts with Milan’s urban morphology to create implicit spatio-temporal borders, and how these borders impact the day-to-day existence of transient subjects.

Italian hospitality: the “Milan Model”

Between the end of the 1990s and the early 2000s, the emergence of international ‘humanitarian crises’ led to a reframing of Italy’s refugee reception and integration legislation that progressively impacted Italy’s migration management policies (Furri 2018). These policies led to a double-track system, designed to facilitate the evaluation of asylum requests and promote the integration of those identified as refugees (Bini & Gambazza 2019). The ordinary track was first established in 2002 and rebranded as the Reception and Integration System (SAI) in 2017. The extraordinary track dates back to 2011, when, with the outbreak of the Arab Spring, the Italian government saw the need for emergency-focused facilities, the Centres of Extraordinary Reception (CAS), managed at the prefectural level. The municipality of Milan subsequently adopted and amended the national approach into what has come known as the ‘Milan Model’.

Milan is the main point of reference for transient subjects across Italy who either stay in Milan or stopover before heading to other European destinations. The ‘Milan Model’ for reception emerged in 2013 with the overwhelming arrival of Syrians escaping the civil war (De Riccardis 2013). To respond to this ‘crisis’, the national approach was amended in different ways. First, this function was moved from the national to the municipal level to facilitate the evaluation of asylum requests. Second, ‘Municipal CASs’ were produced, which received people through municipal rather than national channels, and began to provide basic integration services such as language classes or socio-economic support. Third, the non-profit sector began to play a major role in the management of these facilities. While this model aimed to streamline the reception system, it has led to what can be understood as spatio-temporal borders that transient subjects are left to overcome on their own. These borders are revealed through the process of counter-mapping.

Temporal segregation

The temporal borders transient subjects are faced with in Milan are created by design—by a reception system which leaves them in a constant state of uncertainty, characterized by imperfect knowledge and unpredictability of the future (Horst & Grabska 2015). The design is a product of the emergency scenarios, and as such, is intended to operate under a sense of urgency and immediacy. This is the antithesis of the progressive reception process envisioned by the double-track approach, which does not reflect the asylum-seeking process’s temporal reality. As of 2020, Milan had a total of 86 CASs, with an average capacity of 67 occupants, and a total of 66 SAIs, with an average capacity of 10 occupants. The numeric disproportion in the number and capacity of these facilities is a result of their envisioned purposes—CASs as temporary solutions for large-scale inflows of transient subjects, and SAIs as the longer-term projects for the few subjects who remain and receive protection. In contrast, CASs have become indefinite and longer-term housing solutions, with inhabitants often staying for over a year (ANCI et al. 2017). As a result, occupants are clueless when it comes to the length of their stay in CASs, and therefore unable to begin planning their future. Due to limited availability in SAI programmes, many are forced to leave their CAS without the necessary integration support, even after receiving a positive decision on their asylum applications. As Italy does not have any post-reception housing policies or solutions, transient subjects are forced into precarious housing solutions such as homeless shelters or squatting (MSF 2016).

While the protracted uncertainty transient subjects are faced with has been normalised by bureaucratic inertia and a security imperative (Biehl 2015), it nonetheless produces experiences of continuous waiting and limbo, differently impacted by ethnicity, gender, and class (Conlon 2011; Hyndman & Giles 2011; Mountz 2011). Transient subjects are consequently positioned for extended periods at the border (Darling 2011). These temporal borders are not visible on a map of Milan but rather revealed by the embodied experiences of transient subjects. In a similar vein, the spatial borders created by the physical location of reception facilities are exposed when lived experiences are mapped onto Milan’s urban morphology.

Spatial segregation

Borders have been variously defined as the spaces where law and order are both suspended and enforced (Doty 2011), the processes by which the precarity of migration is structurally created and maintained (Walia 2013), and the instruments of segregation wielded to enforce hierarchies (Gahman & Hjalmarson 2019). The spatial borders transient subjects are faced with in Milan are not limited to the physical barrier between nation-states but are also created by the geospatial distribution of reception centres and the relationship between their geographic position and the location of key public services. These borders are represented through a geospatial analysis of Milan, focusing on the positionality of CASs.

Figure 1 shows the network distance of CASs by occupant type, demonstrating the concentration of facilities in the North and Southeast region of Milan and the predominance of CASs hosting families or men. The geographic concentration of CASs in Milan produces a striking juxtaposition between areas of high, low, or no density of centres. Even within areas of concentration, the distribution is not homogeneous—more CASs are found the farther away from the city centre.

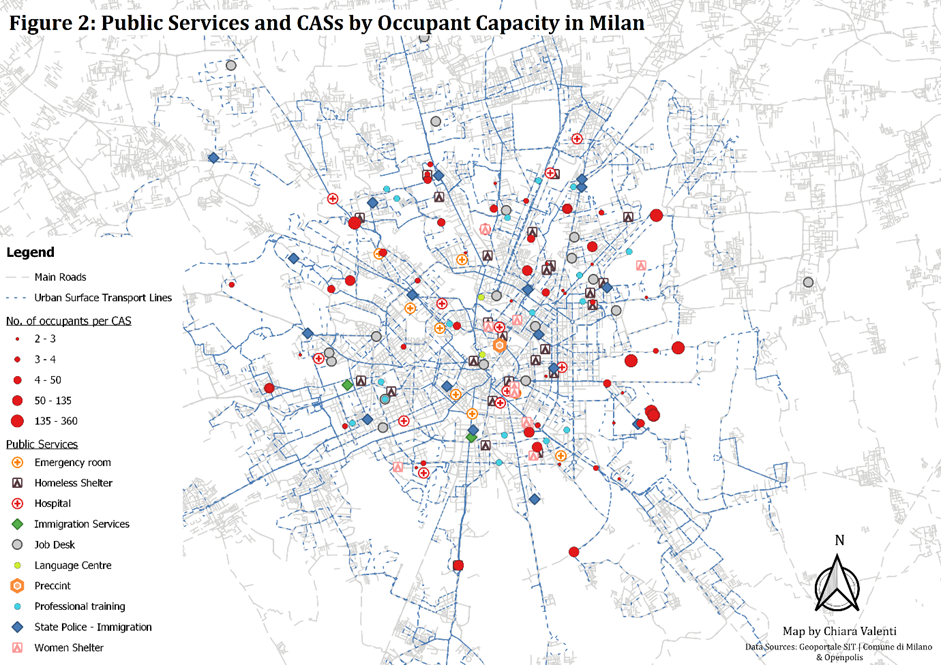

Figure 2 shows the distribution of relevant public services in comparison to CAS capacity. This figure shows how larger CASs are found further from the city centre. Coupled with the geographic concentration of CASs, what this implies is that certain public service facilities are prone to overcrowding, lengthening processing times.

Figure 3 shows the shortest paths to reach the nearest public service facilities via urban surface transport lines from a random selection of different CASs, demonstrating the accumulation of paths from CASs to specific public services. This further demonstrates how certain public service facilities will be prone to overcrowding.

This geospatial analysis depicts how the spatial borders created by the positionality of CASs in Milan constitute a threshold of exclusion (De Genova 2002) that push transient subjects to the city’s periphery as externalities to be managed with little or no effort to integrate them into the city’s social fabric.

Conclusion

This mapping of the ‘Milan Model’ of reception provides a novel cartographical representation of politically marginalised groups (Craig et al. 2002). In refuting the visibilities and temporalities performed by the statist gaze (Tazzioli 2019), the spatio-temporal borders created by this model are revealed. The borders are both the cause and consequence of intrinsic uncertainty and externality through which Milan’s reception system governs transient subjects. Nevertheless, in taking the lived experiences of transient subjects as the starting point of this analysis, they begin to be recognised as spatial actors, continuously re-negotiating and re-signifying urban space and time in order to build a life of their own.