Historical Foundations of Human Rights and Contemporary Crises

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-4sn4-zs17In recent decades, human rights have become omnipresent in our daily lives. This impressive amount of attention is even more stunning if we consider that the expression “human rights” was barely in use before the mid-1940s.

Origins

Where and when were human rights born? How have human rights become today’s powerful doctrine and language of legitimacy? Historians have spent the last 15 years discussing issues of genealogy, but have not found a consensual answer yet. Three historical moments enjoy pride of place in this discussion: the Enlightenment and the 18th century revolutions, notably the French Revolution; the second half of the 1940s, with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); and the 1970s, when, according to some, human rights spilled out of the UN and into the global consciousness of humanity.

For those who locate human rights’ birth in the 18th century, these are akin to natural rights and their appearance in constitutional texts (such as the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen) is enough to proclaim their existence, despite the fact that their reach was limited to the domestic jurisdictions of nation-states and that several groups of people (women, slaves, minorities, among others) remained excluded. Those who privilege the 1940s as the real beginning emphasise that human rights are international rights and the UDHR their founding document. They simultaneously tend to ignore the UDHR’s lack of legally binding nature, the absence of enforcement mechanisms and the virtual inexistence of contemporary grassroots transnational human rights movements. Finally, the adherents of the 1970s thesis understand human rights as rights that go beyond and against the nation-state, meaning that they are both advocated and enforced in the international sphere. Pointing to the strategic or instrumental use of human rights language by as diverse a set of actors as dissident movements in the Soviet space (notably those spearheaded by Valery Chalidze, Andrei Sakharov and Vaclav Havel) and Latin America (among others the Argentinian Permanent Assembly for Human Rights and the Chile Committee for Human Rights), Western NGOs like Amnesty International and Helsinki Watch (later Human Rights Watch), and US President Jimmy Carter, they conclude that it is only in the late 1970s that human rights became the global phenomenon that we know today. Yet, they forget that for most of the global community human rights were not a priority at that time, coming second to the attainment of state sovereignty, economic development and more equal North-South redistribution.

In conclusion, although the human rights historiography of the last 15 years cannot agree on an exact date of birth, it has improved exponentially our knowledge of the long and short history of human rights. This dialogue between different interpretations of the evolution of human rights yields a much richer, less celebratory, and more accurate history of the contested and evolving concept of human rights.

Crisis

The human rights movement, meaning the set of actors that actively promote and defend human rights as a doctrine and an international practice, used to be hegemonic in the 1990s and in the early 2000s. This is no longer the case today. Criticism has come from different corners and become louder. Among the many critiques, three – mostly coming from the Global South – are worth mentioning. According to the first, human rights are a Western Trojan horse used to infringe upon the sovereignty of non-Western people for geopolitical purposes.From such a perspective, human rights amount to a new “standard of civilization” used by powerful states pursuing imperial agendas by other means. The second critique casts human rights as a Western invention incompatible with non-Western cultures portrayed as being more communitarian and less individualistic.The formation of a transnational human rights movement in the 1970s transformed human rights into a global force First formulated in the 1990s by the Singaporean head of state Lee Kuan Yew, this reading of human rights history curiously represents a major break with the past. In 1950, Western politicians, including the French jurist and later Nobel Peace Prize René Cassin, openly opposed an extension of the application of the UDHR to colonial territories on grounds that their populations were not civilized enough. Sixty years later, the tables have turned: while Western actors more often than not defend the universality of human rights, a growing number of non-Western voices rejects it as an alien imposition. Third, the formation of a transnational human rights movement in the 1970s transformed human rights into a global force. But the understanding of human rights that has become dominant within this movement is a minimal doctrine focused more on saving bodies than promoting broader views of social transformation. In the process, social rights have been put on the backburner, eclipsed by the denunciation and prosecution of gross violations of civil and political rights. As Samuel Moyn has argued, in a world of growing inequalities, this minimal understanding of human rights is simply “not enough”.

The Individual and the Group

Several of these critiques tend to come from actors that reject the primacy of international universal norms over the autonomy of the sovereign state. This is not new. Since at least 1945, self-determination has served as the key bone of contention between universalist and particularistic approaches to human rights narratives.

Human rights have traditionally been conceived as individual rights, as the rights that we hold as individual human beings. Yet, humans do not exist in a vacuum. Human rights inevitably relate to a number of collective identities and webs of relations that make a uniquely individualist understanding of human rights highly problematic. As Hannah Arendt observed, “we are not born equal; we become equal as members of a group on the strength of our decision to guarantee ourselves mutually equal rights”. After the Second World War, and more decisively from the 1970s onwards, there has been an effort to turn humanity as a whole into the group that guarantees mutually equal rights.Human rights inevitably relate to a number of collective identities and webs of relations that make a uniquely individualist understanding of human rights highly problematic. Whether this attempt will ultimately succeed is impossible to know. However, today nation-states still provide the primary collective framework for the enforcement of rights. They are among the greatest human rights violators, but also among their first defenders. The imbrication between nation-states and human rights, between the individual and the collective, is still a neglected theme in the historiography of human rights; a frontier to explore, with far-reaching consequences for contemporary political debates on the tension between equality and difference in the application of minority rights, the inclusion of immigrants in social security systems, or the degree of precedence that universal human rights norms should have over the democratic decisions of particularistic communities

Electronic reference

Dalle Mulle, Emmanuel. “Historical Foundations of Human Rights and Contemporary Crises.” Global Challenges, no. 11, March 2022. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/11/historical-foundations-of-human-rights-and-contemporary-crises. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-4sn4-zs17.BOX: Human Rights across and beyond Cold War Divisions

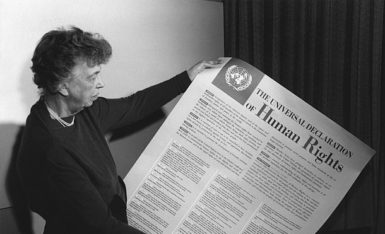

Eleanor Roosevelt holding poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in English), Lake Success, New York. November 1949.

Eleanor Roosevelt holding poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in English), Lake Success, New York. November 1949.In the post-1945 period, different understandings of human rights arose, were advocated, and often blatantly violated, across and beyond Cold War divisions in complex and unexpected ways. A standard version of human rights history portrays Western countries as strong supporters of civil and political rights and the Soviet bloc as staunchly defending social, economic and cultural rights. This dichotomy is correct only if we conceive of it as a matter of emphasis, rather than essence. True, in the late 1940s, many Western governments were sceptical of the justiciability of social and economic rights. By contrast, the Soviet Union branded social rights as an ideological weapon to denounce the inequalities inherent in capitalist societies. Yet, one should not forget that the years between 1945 and 1975 were the “golden age” of the welfare state. Hence, although, broadly speaking, in the West social and economic rights were seen as more aspirational than civil and political rights, there was strong consensus that they had to be included in key documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the two later human rights covenants (although doubts about justiciability resurfaced in the negotiations for the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, which eventually excluded them). A matter that divided much more strongly East and West in the late 1940s was the inclusion of collective rights, notably minority rights, in the UDHR. Most Western delegations defended an individualist (and assimilationist) understanding of human rights, arguing that non-discrimination clauses would be sufficient to protect minorities. Communist countries, by contrast, strongly advocated the inclusion of an article on the cultural and linguistic rights of minorities.

These disagreements notwithstanding, in the late 1940s, the US and the USSR did agree that any serious step towards implementation had to be put off for the foreseeable future. In the following two decades, they defended their respective emphasis on individual or collective rights, wielding their own understanding as an ideological weapon to denounce violations in the opposite bloc, but doing little to advance enforcement. Within this confrontation, in the 1960s, postcolonial countries emerged as a key human rights player. Shifting the focus over matters of racial discrimination and self-determination, they reenergised the human rights agenda at the UN, as witnessed by the adoption of the first legally binding human rights treaties: the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), in 1965, and the two International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), in 1966 – the 1948 Genocide Convention was not generally considered as a human rights treaty in the late 1940s as it is today. Postcolonial human rights advocacy at the UN in the 1960s challenges claims that human rights are simply a Western invention imposed on the Global South. Yet, by the early 1970s, the “honey moon” between human rights and postcolonial states was over. The spread of authoritarian regimes committing serious human rights violations and a heavier concern with North-South economic redistribution reduced Global South’s interest in advancing human rights at the UN. Hopes that the Global South could lead a human rights revolution were dashed.

It is within this general mood of disillusion that the “human rights breakthrough” of the second half of the 1970s occurred. The international human rights movement that arose then portrayed itself as apolitical, as appealing to a “higher morality” escaping the polarised logic of the Cold War. Not surprisingly, one of Amnesty International most successful campaigns consisted in choosing three political prisoners, one each from the First, Second, and Third World (in then language). As Andrei Sakharov made clear, “what we need is the systematic defence of human rights and ideals and not a political struggle” (Sakharov Speaks, Alfred A. Knopf, 1974, p. 44). Contemporary understandings of human rights have much to do with a commitment to protecting human lives from harm as with scepticism about grand ideological projects of political and social transformation. Whether human rights can legitimately claim to be a minimal ideology based purely on morality is however debatable, as recent criticism of its supposed universality suggests.

Emmanuel Dalle Mulle

Research Associate at the Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

Postdoctoral Researcher, Complutense University of Madrid

PODCAST: Human Rights and the International Criminal Court with Paola Gaeta

Global Challenges n° 11 – The Uncertain Future of Human Rights. With Dominic Eggel and Marc Galvin (Research Office – The Graduate Institute, Geneva)

PODCAST: The Universality of Human Rights with Huaru Kang

Global Challenges n° 11 (The Uncertain Future of Human Rights). With Dominic Eggel and Marc Galvin (Research Office – The Graduate Institute, Geneva)

PODCAST: Human Rights and Social Media with Stefania Di Stefano

Global Challenges n° 11 – The Uncertain Future of Human Rights. With Dominic Eggel and Marc Galvin (Research Office – The Graduate Institute, Geneva)

PODCAST: Human Rights versus Nature and Animals Rights? with Anna Ploeg

Global Challenges n° 11 – The Uncertain Future of Human Rights. With Dominic Eggel and Marc Galvin (Research Office – The Graduate Institute, Geneva)

PODCAST: Human Rights and Business, with Jérôme Bellion-Jourdan

Global Challenges n° 11 – The Uncertain Future of Human Rights. With Dominic Eggel and Marc Galvin (Research Office – The Graduate Institute, Geneva)

PODCAST: Human Rights Narratives with Tomas Morochovic

Research Office – Graduate Institute, Geneva.

VIDEO: Human Rights and Humanitarian Law in the 21st Century, with Gloria Gaggioli

Global Challenges n° 11 – The Uncertain Future of Human Rights – The Graduate Institute, Geneva

TIMELINE: Major International Human Rights Treaties

The Universal Declaration was the first detailed expression of the basic rights and fundamental freedoms to which all human beings are entitled.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the UN in an effort to prevent atrocities, such as the Holocaust, from happening again. The Convention defines the crime of genocide.

The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees protects the rights of people who are forced to flee their home country for fear of persecution on specific grounds.

The Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention (No. 111) of the International Labour Organization prohibits discrimination at work on many grounds, including race, sex, religion, political opinion and social origin.

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) obliges states to take steps to prohibit racial discrimination and promote understanding among all races.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) protects rights like the right to an adequate standard of living, education, work, healthcare, and social security. The ICESCR and the ICCPR (below) build on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by creating binding obligations for state parties.

Human rights protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) include the right to vote, the right to freedom of association, the right to a fair trial, the right to privacy, and the right to freedom of religion. The First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR creates a mechanism for individuals to make complaints about breaches of their rights. The Second Optional Protocol concerns abolition of the death penalty.

Under the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), states must take steps to eliminate discrimination against women and to ensure that women enjoy human rights to the same degree as men in a range of areas, including education, employment, healthcare and family life. The Optional Protocol establishes a mechanism for making complaints.

The Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169) of the International Labour Organization aims to protect the rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples around the world. It is based on respect for the right of Indigenous peoples to maintain their own identities and to decide their own path for development in all areas including land rights, customary law, health and employment.

The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families aims to ensure that migrant workers enjoy full protection of their human rights, regardless of their legal status.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities aims to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights by persons with disability. It includes the right to health, education, employment, accessibility, and non-discrimination. The Optional Protocol establishes an individual complaints mechanism.

This Declaration establishes minimum standards for the enjoyment of individual and collective rights by Indigenous peoples. These include the right to effectively participate in decision-making on matters which affect them, and the right to pursue their own priorities for economic, social and cultural development.

This Declaration asserts that everyone has the right to know, seek and receive information about all human rights and fundamental freedoms and should have access to human rights education and training.

Based on the information produced by the Australian Human Rights Commission