Watering Down Human Rights? A Healthy Environment for the Rights to Water and Sanitation

Water is a scarce global resource and one that is particularly vulnerable to neoliberal capture by governments and companies. To ensure the rights to water and sanitation for all, increased cooperation between international agencies is essential, along with an approach that also allows for participation by representatives of the world’s most vulnerable groups.

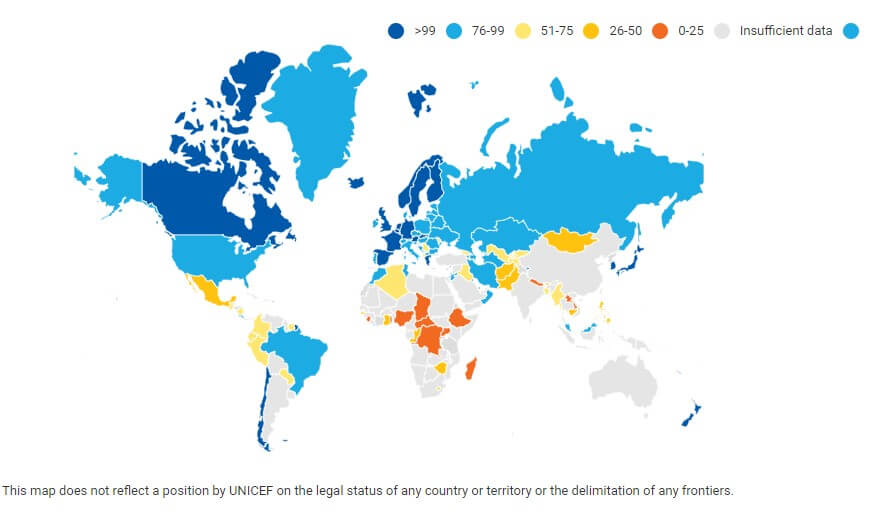

A healthy environment is key to the enjoyment of human rights.[1] Indigenous peoples are particularly vulnerable to climate change; for example, those living in the Arctic region or in mountain areas depend on water from glaciers. Many islanders and coastal inhabitants risk losing their place to live because of rising sea-levels, caused not only by climate change but also by increasing groundwater extraction prompting ground levels to sink. Worldwide, 1 in 5 children does not have enough water for personal use, in large parts due to growing water vulnerability, floods and droughts.

Climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution endanger the globe and undermine people’s rights to life, health, food and water. These aggravating conditions are leading to increased interaction between the human rights and the climate regime as expressed in the formation of issue-merging super-networks of human rights and climate activists such as the inter-constituency alliance for incorporating human rights in the 2015 Paris Agreement (Schapper 2021).

Another manifestation of this growing interdependence of the two regimes is the “greening” of the human rights regime through various policies and regulations (Lizarazo-Rodriguez 2021). One recent example is the Human Rights Council resolution 48/13, adopted on 8 October 2021, which recognises the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right that is key to the enjoyment of human rights more generally, both substantively (e.g. the right to life) or procedurally (e.g. access to justice). Among the rights the Council lists as especially affected by climate change are the rights to water and sanitation (RTWS), rights that were not included in the International Bill of Rights (consisting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its two Optional Protocols), but later interpreted from the right to an adequate standard of living and the right to health. The existence of these rights is a story of contestation and rights advocacy, as they were championed by environmental groups since the 1970s (Reiners 2021). Progress in this area was typically possible because advocates collaborated across sectors and repeatedly called attention to human rights-related impacts of water access and quality at multilateral conferences and meetings.

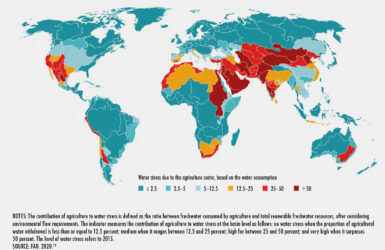

Today, the realisation of RTWS requires special measures and more collaboration in relation to environmental challenges.[2] RTWS are especially vulnerable to neoliberal capture by governments and companies (Baer 2017) who set the prices for the provision of water infrastructure and therefore risk compromising standards in global policy initiatives (Langford and Winkler 2014) or aggravating inequalities (Truelove 2011). The scarcity of water as a global resource highlights the necessity for a universal human rights approach to RTWS. The scarcity of water as a global resource highlights the necessity for a universal human rights approach to RTWS. Such a universal approach, however, is contested by anthropologists who point to the unique reality of indigenous peoples living at rivers – suggesting that water as a human right and a natural resource is not conceptually exhaustive (Viaene 2021). As a result, the question arises how the international human rights regime may guarantee the enjoyment of RTWS for the future while doing a better job in accounting for the pluralities of water and environment relationships across the globe. Here are some answers to that question.

- Taking a comprehensive, global and intersectional approach: To reach this aim, policy proposals should reflect a participatory process in which experts from different backgrounds, vulnerable groups and affected individuals provide input. Strong human rights standards are also more likely to materialise when more than just legal expertise is considered in the decision-making process. Moreover, processes will have to take place globally, and not just in Geneva or New York. Special Rapporteurs and their country visits are a step in the right direction, as the human rights institutions should come to the people and to the sites of water and environmental conflicts. RTWS are linked to practical challenges like access to water that frequently require long travels to rural areas in need, for instance, of expert inputs from engineers on water infrastructure.

- Fostering inter-institutional cooperation: A comprehensive approach to realising RTWS in light of current environmental challenges requires the UN human rights bodies to reach out and collaborate with other institutions such as the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).A comprehensive approach to realising RTWS in light of current environmental challenges requires the UN human rights bodies to reach out and collaborate with other institutions such as the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) It should become the rule rather than the exception that international organisations and UN agencies take the opportunities offered by the UN human rights bodies to speak on days of general discussion or submit statements on topics relevant for the elaboration of general comments. More importantly, this cooperation should be facilitated through country offices rather than headquarters, as the inclusion of local actors and civil society is crucial in this process.

- Highlighting the indivisibility of human rights: Human rights are indivisible and interdependent, meaning one right cannot be fulfilled without the others. Environmental challenges have brought this principle to the forefront, and RTWS are no exceptions. All human rights treaty bodies should continue to include water- and sanitation-related aspects in their monitoring work. In their latest interpretation on the right to life in 2018, the Human Rights Committee for the first time connected RTWS to the right to a healthy environment.

- Strengthening mandates of the Independent Experts: The Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council are independent human rights experts with mandates to report and advise on human rights from a thematic or country-specific perspective. They need enough resources to fulfil their mandate and to collaborate on the future of RTWS and related environmental issues. Previous examples of thematic reports on human rights and the global water crisis include topics like water pollution, water scarcity, water-related disasters as well as the dependence of human rights on a healthy biosphere. Of particular importance are the Special Rapporteurs on human rights and the environment, on safe drinking water and sanitation, on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes, and the recently established mandate on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change.[3]

The recognition of a right to a healthy environment at the international level in 2021 was celebrated as a landmark for the protection of people and nature. Yet, its monitoring and implementation will put further pressure on an already overburdened and contested UN regime with the risk of watering down human rights as global norms. Within the UN regime, a chronically underfunded human rights system now also needs to provide the expertise on all environment-related aspects of human rights law and policies. With its central hub of knowledge exchange in Geneva, this system excludes many organisations and individuals from participating and presenting their claims to water and environment rights. Without the representation of all marginalised and vulnerable voices, human rights will further lose support.

[1] See “OHCHR and Climate Change”.

[2] See also the Special Thematic Report on Climate Change and the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation by the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation (January 2022) available on this page.

MAP: Proportion of Population Using Safely Managed Drinking Water Services, 2020 (%)

Source: WHO/UNICEF JMP, Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2020: Five years into the SDGs, 2021

TIMELINE: Major International Human Rights Treaties

The Universal Declaration was the first detailed expression of the basic rights and fundamental freedoms to which all human beings are entitled.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the UN in an effort to prevent atrocities, such as the Holocaust, from happening again. The Convention defines the crime of genocide.

The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees protects the rights of people who are forced to flee their home country for fear of persecution on specific grounds.

The Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention (No. 111) of the International Labour Organization prohibits discrimination at work on many grounds, including race, sex, religion, political opinion and social origin.

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) obliges states to take steps to prohibit racial discrimination and promote understanding among all races.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) protects rights like the right to an adequate standard of living, education, work, healthcare, and social security. The ICESCR and the ICCPR (below) build on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by creating binding obligations for state parties.

Human rights protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) include the right to vote, the right to freedom of association, the right to a fair trial, the right to privacy, and the right to freedom of religion. The First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR creates a mechanism for individuals to make complaints about breaches of their rights. The Second Optional Protocol concerns abolition of the death penalty.

Under the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), states must take steps to eliminate discrimination against women and to ensure that women enjoy human rights to the same degree as men in a range of areas, including education, employment, healthcare and family life. The Optional Protocol establishes a mechanism for making complaints.

The Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169) of the International Labour Organization aims to protect the rights of Indigenous and tribal peoples around the world. It is based on respect for the right of Indigenous peoples to maintain their own identities and to decide their own path for development in all areas including land rights, customary law, health and employment.

The International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families aims to ensure that migrant workers enjoy full protection of their human rights, regardless of their legal status.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities aims to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights by persons with disability. It includes the right to health, education, employment, accessibility, and non-discrimination. The Optional Protocol establishes an individual complaints mechanism.

This Declaration establishes minimum standards for the enjoyment of individual and collective rights by Indigenous peoples. These include the right to effectively participate in decision-making on matters which affect them, and the right to pursue their own priorities for economic, social and cultural development.

This Declaration asserts that everyone has the right to know, seek and receive information about all human rights and fundamental freedoms and should have access to human rights education and training.

Based on the information produced by the Australian Human Rights Commission