A New Page in Global Sanctions Practice: The Russian Case

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has wreaked havoc and devastation on Ukraine and its people, while posing one of the largest threats to European security and stability since the Second World War. Shockwaves from the war have reverberated around the world, impacting on financial markets, energy prices, supply chains and food security. This has served to exacerbate an already perilous situation for many countries struggling to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sanctions – an ever popular, yet polarising and contested, instrument of foreign and security policy – sit at the forefront of the West’s response to the Russian aggression in Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, sanctions have not been adopted through the United Nations (in light of Russia’s permanent membership of the UN Security Council [UNSC]) and are instead employed by a large coalition of countries, including those in the European Union and the G7.

Sanctions have long been an instrument of choice for addressing global security issues

Global sanctions practices are indeed changing at a fast pace, as policymakers seek to keep up with the changing face of international relations.[1] Sanctions frequently serve as a flexible and relatively low-cost counterpoint to diplomacy and war, to address a plethora of global security challenges including the outbreak of new conflicts and humanitarian crises, developments in the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, the activities of non-state armed groups (such as terrorist organisations) and hybrid threats. It is now difficult to imagine a geopolitical landscape without them. As technological developments accelerate around the world, so does the sophistication of sanctions, as well as due diligence tools to ensure compliance by private and not-for-profit sectors.Sanctions frequently serve as a flexible and relatively low-cost counterpoint to diplomacy and war

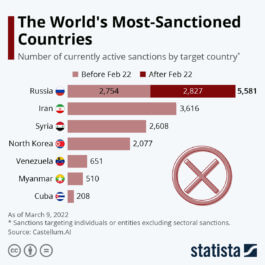

A range of governments, international organisations (IOs) and regional organisations make active use of sanctions, closely combining them with other policy instruments, such as diplomacy, trade, defence and referrals to legal tribunals. Sanctions are often imposed alongside a range of other related, yet distinct, regulations, such as counterterrorism measures, anti-money-laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism legislation (AML/CFT), anticorruption measures and export controls. Globally, the use of sanctions is expanding exponentially with an increased number of actors and targets involved. By some estimates, around a third of the world’s population now live under one or more sanctions regimes. The extent to which ordinary civilians are impacted, however, depends on various factors, among others the type of sanctions employed and their repercussions on financial inclusion, supply chains and humanitarian activities.

Historically, the US and the EU have been the most active sanctions users

When it comes to the use of sanctions, the United States takes first place – representing the world’s most active user of sanctions, as well as their most aggressive enforcer. Some estimates suggest that the US has adopted up to five times more sanctions than the UN in recent years, with over 150 different sanctions regimes in place since the end of the Cold War (Attia and Grauvogel 2019).

Second comes the EU – the only regional organisation to use restrictive measures (their term for sanctions) as an external tool of foreign and security policy. The EU has used around three times more sanctions than the UN, according to Attia and Grauvogel (2019). The EU’s sanctions, which are adopted via consensus among the bloc’s 27 member states, hold considerable weight in light of the EU’s leading role in global trade and finance and its prominence as a leading normative actor and humanitarian power. The EU tends to align its sanctions closely with those of the US, while typically acting as a more dovish counterpoint on some targets and topics (Cardwell and Moret 2022).

Third is the UK, adopting sanctions independently since its departure from the EU but retaining an important role given the City of London’s key role in financial sanctions. To date, its measures have remained closely aligned with those of the EU (Moret and Pothier 2018). Fourth is Canada, which amended its legislation in 2017 to allow its government to adopt autonomous sanctions, even in the absence of similar actions from major trade partners.

Autonomous sanctions practices are typically now led by this new “sanctions quartet” composed of the US, EU, UK and Canada, sometimes working with other countries (including Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and Switzerland). These type of ad-hoc coalitions of likeminded partners reflect similar types of informal governance arrangements in wider European and transatlantic security and defence cooperation.

Many autonomous sanctions regimes adopted by the likes of the US and EU target the export of dual-use goods (technologies and other items that could have both civilian and military applications). The aim of such export controls is to permit the trade of consumer goods to targeted countries while also cutting access to any technology that could support their militaries, including in relation to the use of weapons of mass destruction.

Sanctions are no longer an exclusively Western policy instrument

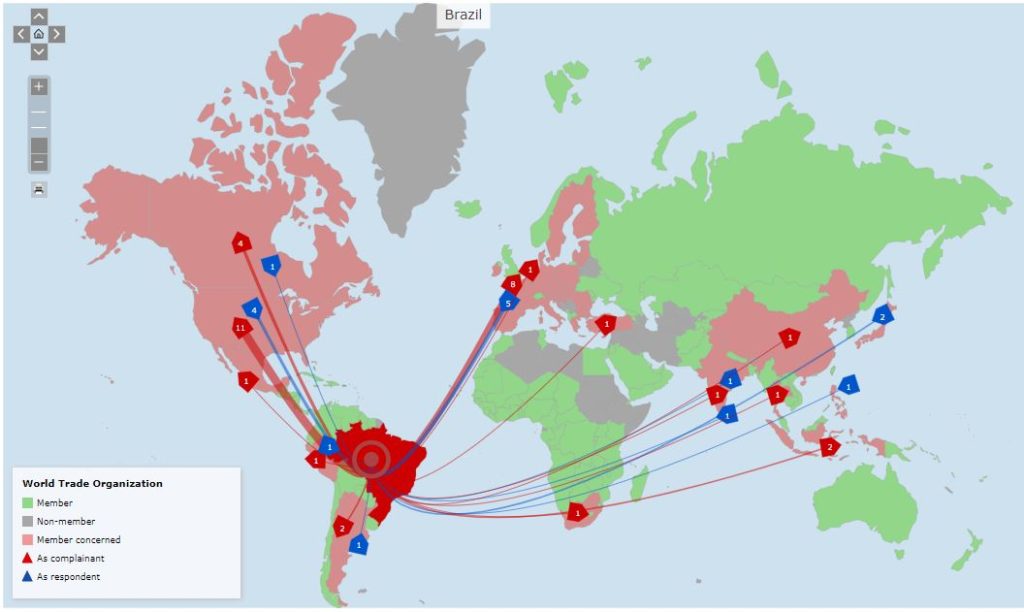

Sanctions remain an overwhelmingly Western tool, implying a major power imbalance given that the majority of targets are in the Global South. In spite of this, there are a number of other states across the Middle East, Asia, Africa and Latin America that have (sometimes quietly) started to use, or develop, their own sanctions regimes (Moret 2021). India, for example, has traditionally opposed the use of unilateral sanctions by the West, but has a long history of using the tool for its own domestic purposes (Chauhan 2013).Sanctions remain an overwhelmingly Western tool, implying a major power imbalance given that the majority of targets are in the Global South

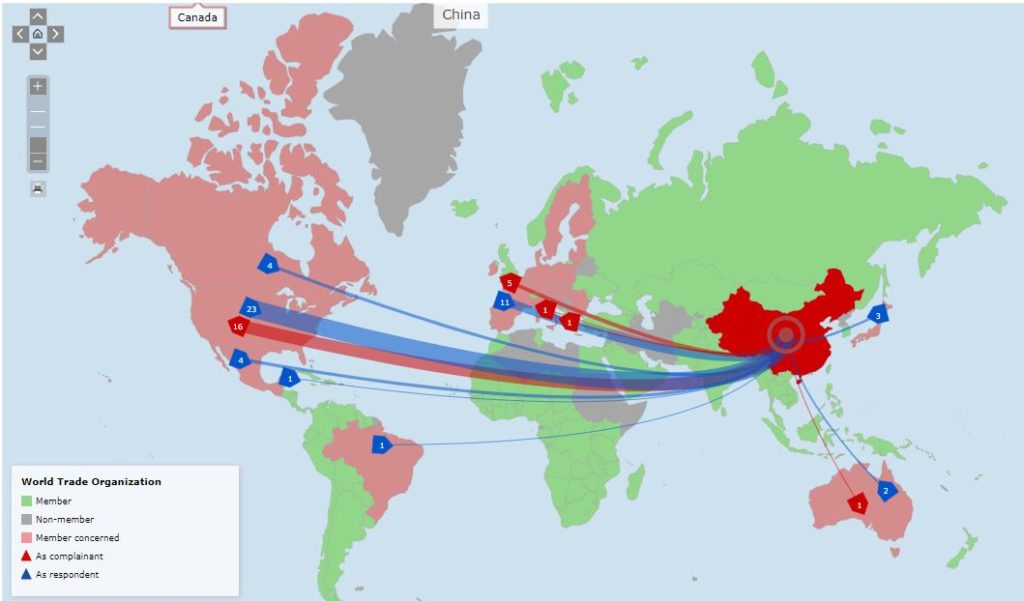

China has long used unilateral coercive measures for a range of purposes, often justified in terms of protection of national security interests. This has included quarantine measures, non-tariff barriers, cancellations of leadership visits and state-driven commercial boycotts (as well as selective purchases) (Reilly 2012). In addition to using its own autonomous sanctions that supplement UN measures against North Korea (Jiang 2019), China established a set of legislations in 2021 to use autonomous sanctions in a greater range of contexts, including export controls and other measures to protect Chinese commercial interests.

Russia, which has long-driven narratives arguing against the use of autonomous sanctions, has nevertheless made long use of what might be termed “sanctions by other names”. This has included controls on agricultural imports, diplomatic and travel restrictions, asset freezes, air traffic bans, alterations to export and import tariffs and halts to gas supplies (Moret et al. 2016).

The current sanctions regime against Russia is unusually broad in scope

In the current context of the war in Ukraine, international sanctions imposed against Russia are broad-ranging and among the strictest sanctions regimes in the world. Measures imposed by the US, the EU and others include asset freezes; travel and visa bans; diplomatic restrictions; prohibitions on the provision of funds and restrictions on access to capital markets – intended to erode Russia’s industrial base (including in relation to the financial sector and its ability to make use of the financial messaging system SWIFT). They also feature measures targeting Russia’s energy and transport sectors; export and import bans and restrictions such as on steel, cement, gold, advanced semiconductors, oil and coal. There is in addition a tightening and extension of sanctions on dual-use goods.

Together, these measures seek to target sensitive sectors in Russia’s military industrial complex, limit Russia’s access to crucial advanced technologies, degrade Russia’s ability to fund and orchestrate its war efforts in Ukraine, and place pressure on elites surrounding President Putin. In many ways, they resemble sanctions used elsewhere but they are unusual in other ways (Moret 2022).

First, they were agreed by an international coalition of countries and organisations with unrivalled speed. In a matter of weeks, a complex set of overlapping sanctions regimes and expanded measures relating to export controls were agreed and adopted by over 30 countries.

Second, this is the first time in recent history that a major G20 economy, a permanent member of the UNSC and a leading energy supplier has been targeted through such sweeping sanctions, including central bank restrictions.

This unique hub displays how sanctions can be critically studied across the full variety of academic disciplines, so as to increase awareness among multi-stakeholder communities of the historical, sociological, economic and legal complexities associated with the design and implementation of sanctions across a wide range of country and issue domains.

This unique hub displays how sanctions can be critically studied across the full variety of academic disciplines, so as to increase awareness among multi-stakeholder communities of the historical, sociological, economic and legal complexities associated with the design and implementation of sanctions across a wide range of country and issue domains.Third, is the mass voluntary boycott of Russia by over a thousand international firms, which formerly accounted – by some estimates – for some 40% of Russia’s GDP. Such moves amplify the impacts of the sanctions and deal a highly symbolic, as well as material, blow to the Russian government.

Fourth, the measures are also unusual in relation to a new, and more institutionalised, use of international coordination on their design and enforcement. An example is the joint Russian Elites, Proxies and Oligarchs (REPO) Task Force, composed of the G7, Australia and the EU, which serves to coordinate financial sanctions against kleptocrats’ assets.

Fifth, there are ongoing transatlantic discussions on the legality of whether seized oligarchs’ assets could be used to support Ukraine’s reconstruction or humanitarian response.

Sixth, this marks a rare instance where the target of the sanctions is capable of retaliating in a plethora of devastating ways. this marks a rare instance where the target of the sanctions is capable of retaliating in a plethora of devastating ways. Russia’s hybrid arsenal includes agricultural import and export controls, suspensions of energy supplies and the use of hybrid warfare such as cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, electoral interference and other destabilising actions. Russia has also made documented use of chemical weapons in Europe (against residents of a fellow member of the UNSC in the United Kingdom), not to mention the Kremlin’s ramping up of nuclear threats. That Western countries, and particularly those in close proximity to Russia in Europe, are still prepared to make use of such sweeping measures against a formidable adversary shows how seriously they view the threat and the immense strategic weight they afford sanctions as a policy instrument at the current time.

New applications for economic sanctions have emerged from the Russian case

With the return of war on European soil, sanctions have entrenched themselves as the foreign and security policy tool of choice for many. Their use is part of a wider trend which has seen sanctions proliferate around the world on many levels, raising a plethora of new considerations and challenges, including legal questions, debates on efficacy and ethics, and the need to mitigate unintended consequences. In the Russian context, the use of sanctions also extends way beyond current multilateral export control regimes and exemplifies new forms of cross-border collaboration, not seen since the end of the Cold War. While Ukraine’s future remains uncertain, one thing is sure: the international sanctions response against Russia marks a new page in global sanctions practice.

[1] Erica Moret, “More Civilian Pain than Political Gain (Again?): The Demise of Targeted Sanctions and Associated Humanitarian Impacts”, chap. 11 in Charron and Portela (2022).

VIDEO: A critical analysis of the weaponisation of economics, by Beatrice Weder di Mauro

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute.

VIDEO: Why integrated trade networks matter, with Richard Baldwin

VOXeu and CEPR (Geneva Graduate Institute)

PODCAST: Are we moving towards a new economic cold war? with Cédric Dupont

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute. Globalchallenges.ch

PODCAST: Economic nationalism in the light of the long-term history of capitalism, with Gopalan Balachandran

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute. Globalchallenges.ch

PODCAST: Overview of the WTO challenges in 2022, with Manuel Miranda

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute, 2022. Globalchallenges.org

PODCAST: China and the changing global economic landscape, with Sung Min Rho

Research Office, Geneva Graduate Institute. Globalchallenges.ch

PODCAST: The Economic Weapon in Global Governance, with Nicholas Mulder

Geneva Graduate Institute

DEFINITIONS related to sanctions and economic warfare

Economic and financial sanctions are enforcement actions taken by a country or a group of countries against a targeted state, group, or individual that has been found in non-compliance with existing international law, treaty obligations and customary rules. They can take many forms, like restrictions on commercial or financial transactions, asset freezes, travel bans, or the withholding of economic and technical assistance. They pursue a variety of social, commercial and/or political objectives depending on the kind of violations committed by the target group or state. Usually, they are supposed to coerce targets of sanctions into compliant behaviour, but often, they serve to deter third countries from pursuing similar violations of international law commitments. As an enforcement action, sanctions are supposed to refer to a specific violation of existing law, rather than constitute a purely political measure.

An embargo is the partial or complete proscription of commerce with a particular country or a group of countries. It entails the ban of imports or exports of certain items, or whole sectors, or all products from or to a specified country. One of the most famous illustrations is the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 in retaliation to Western support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. As a barrier to trade, an embargo should not be confused with a military blockade, although enforcement of the embargo could escalate into a military intervention. In contrast to sanctions, which are conceived as enforcement actions, an alliance of states can decide to erect an embargo based on political reasons, for instance, to help allies involved in a conflict by weakening the economy of inimical states.

Sanctions have been used to advance a range of foreign policy goals, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, nonproliferation, democracy and human rights promotion, conflict resolution, and cybersecurity. Sanctions, while a form of intervention, are generally viewed as a lower-cost, lower-risk course of action between diplomacy and war. Still, the costs of sanctions are harder to measure, and human costs can be very high, especially when a whole economy is sanctioned, as in the case of “comprehensive sanctions” against Iraq in the 1990s, or when the whole financial system of a country is crippled, as in the case of “massified” targeted financial sanctions against Iran in the early 2010s.

As the UN’s principal crisis-management body, the Security Council (UNSC) may respond to global threats by imposing sanctions against states and nonstate groups who are found in non-compliance of international law. Sanctions resolutions must pass the fifteen-member council by a majority vote and without a veto from any of the five permanent members: the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The most common types of UN sanctions, which are binding for all member states, are asset freezes, travel bans, and arms embargoes. UN sanctions regimes are typically managed by a special committee and a monitoring group. The global police agency INTERPOL assists some sanctions committees, but the UN has no independent means of enforcement and relies on member states, many of which have limited resources and little political incentive to prosecute noncompliance. Still, the private sector, and especially banking institutions, have come to integrate the names of front companies found in the reports of UN monitoring groups that document evasion practices of specific UNSC sanction regimes, which demonstrates the centrality attained by the UNSC in the management of sanctions. Prior to 1990, the UNSC had imposed sanctions against just two states: Southern Rhodesia (1966) and South Africa (1977), but there has been a long history of sanctions by the League of Nations, of which the UN is the successor organisation.

The European Union imposes sanctions, known more commonly in the 28-member bloc as “restrictive measures”, as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. Because the EU lacks a joint military force, many European leaders consider sanctions the bloc’s most powerful foreign policy tool, based on the experience attained during the early 2010s in the nuclear negotiation with Iran that lead to the signature of the JCPOA in 2015. Sanctions policies must receive unanimous consent from member states in the Council of the European Union, the body that represents EU leaders. Since its inception in 1992, the EU has levied sanctions more than 30 times (in addition to those mandated by the UN). Analysts say the “massified” targeted sanctions the EU bloc imposed on Iran in 2012 – which it lifted in 2015 as part of the Iran nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) – marked a turning point for the EU, which had previously sought to limit sanctions to specific individuals or companies.

The United States uses economic and financial sanctions more than any other country. Sanctions policy may originate in either the executive or legislative branch. Presidents typically launch the process by issuing an executive order (EO) that declares a national emergency in response to an “unusual and extraordinary” foreign threat, for example, “the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons” (EO 12938) or “the actions and policies of the Government of the Russian Federation with respect to Ukraine” (EO 13661). Many US sanctions regimes are administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), located in the Department of the Treasury: OFAC is often considered an all-powerful organisation, as it is in charge of sanctions designations, sanctions exemptions and humanitarian licenses, and examination of delisting requests.

Economic nationalism is an ideology that advocates bolstering and protecting national economies in an effort to countenance or counteract the effects of trade liberalisation and globalisation. It aims to maximise national self-reliance by reverting to elements of protectionism and mercantilism. Economic nationalism privileges state control and interventionism over market mechanisms, profit maximisation and growth. It typically restricts flows of labour, capital, goods and services through protectionist measures such as tariffs, investment controls or export restrictions.

Reshoring is the opposite of offshoring. It refers to companies repatriating “back home” parts or all of their supply chains components, including back-office, manufacturing, or R&D processes. Nearshoring and friendshoring obey a logic similar to reshoring, but instead of production and manufacturing being repatriated back to the “home country”, they are relocated to neighbouring (nearshoring) or allied countries (friendshoring).

Research Office, Geneva Graduated Institute. Questions largely inspired by the Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org.