The Rise of Geoeconomics

An increasingly interconnected world brings opportunities for greater prosperity, but also for greater economic competition between countries. From China’s Belt and Road Initiative to the recently passed CHIPS and Science Act in the US, countries around the world have taken a range of new economic policy measures to protect key domestic industries and to ensure a reliable supply of critical raw materials.

From the Covid-19 pandemic to the Suez Canal blockage to the war in Ukraine, singular events can yield ripple effects throughout the global landscape, causing political and economic disruptions. Due to the unprecedented speed of technological innovation in information and communication capabilities alongside the opening of global markets since the latter half of the 20th century, globalisation’s latest iteration has made countries more interdependent and the world a much smaller, densely connected network. This “Great Convergence”, as the economist Richard Baldwin coined it, has afforded global actors several opportunities for prosperity and development, but concurrently intense competition, exceptional policy challenges, and clashes.

The end of the Cold War in the 1990s marked a turning point in the way global politics would be conducted. Geopolitics, the traditional driving force behind foreign policy and strategy, would be replaced by geoeconomics – a term accredited to the American strategist and military consultant Edward Luttwak. Although the term is loosely defined, geoeconomics dictates that states employ their economic and policy instruments – such as investment policies, commodity restrictions, and financial sanctions – to achieve geopolitical aims, thereby promoting and securing national interests.deep economic integration has led to the exponential weight of economic policy instruments for global powers and aspirants alike to achieve strategic objectives

While military strength remains a significant determinant of power and status, deep economic integration has led to the exponential weight of economic policy instruments for global powers and aspirants alike to achieve strategic objectives through carrot (e.g., aid) or stick (e.g., sanctions) policies. As spheres of influence and political interests overlap, rival powers have triggered a return to power politics and the rise of “weaponized interdependence” – the strategic use of political and economic power and authority to guide or shape international policymaking and political behaviour.

Global Investment Projects, Economic Retaliation and Trade Wars

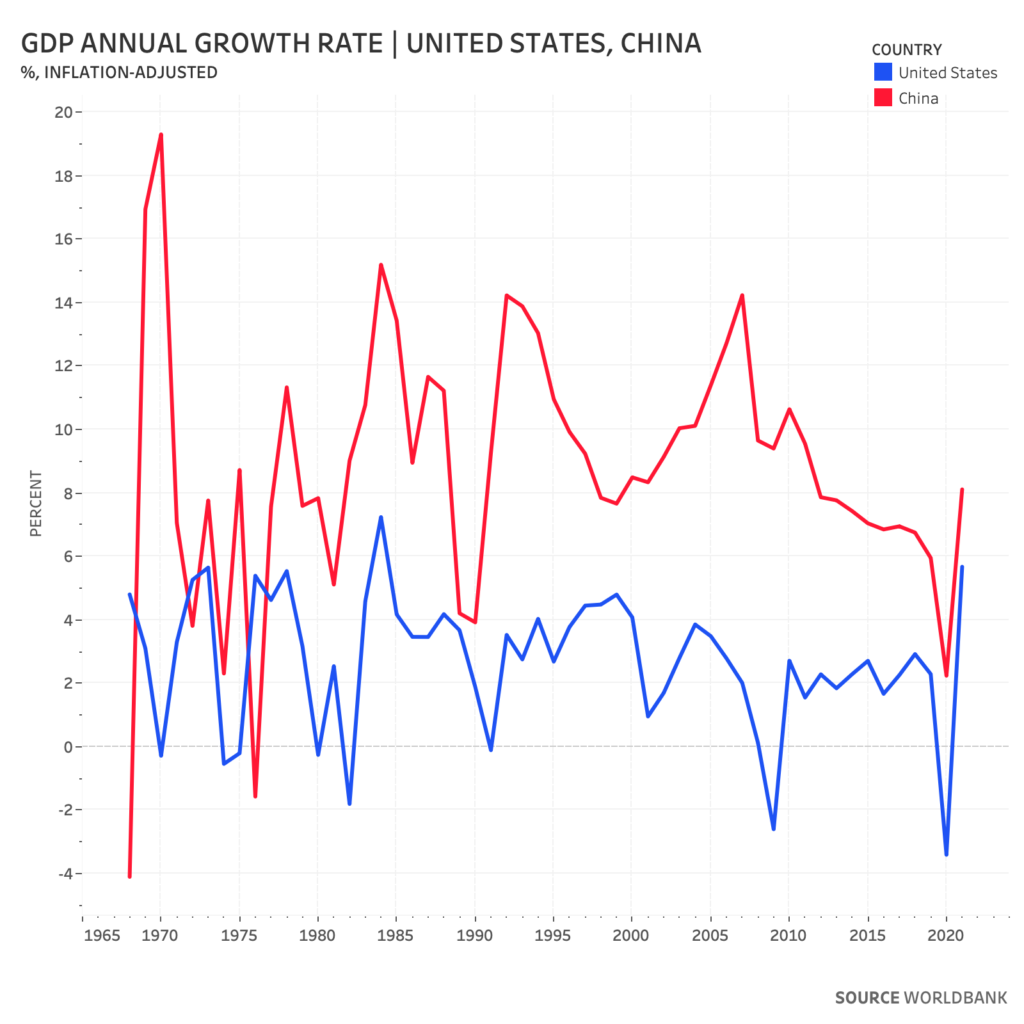

Geoeconomics has thus become the means through which contesting powers, strategically aligned or otherwise, engage in competition or cooperation. Foreign investment and official development assistance have become an integral part of geoeconomics as they grant donor countries immense political favour and diplomatic leverage in exchange for investments in development projects that address infrastructure gaps and build capacities for trade. Fifty years after Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 and subsequent economic reform or “opening-up,” China’s economy has achieved meteoric growth. This economic transformation has made it one of the most prominent and well-equipped geoeconomic actors – rivalling the economic power and influence of the United States.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s ambitious multi-trillion-dollar global infrastructure development project launched in 2013, has sought to revitalise and expand the Silk Road, connecting Asia with Europe and Africa through a network of ports and transnational railroads. The United States, together with its G7 partners, and the European Union have since launched analogous global investment programmes – Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment and Global Gateway, respectively – to engage in strategic competition with the rising power and counter its geopolitical ambitions.

Geoeconomics has thus become the means through which contesting powers, strategically aligned or otherwise, engage in competition or cooperation. Intense global competition at the firm level has further fragilised the relationship between the United States and China as each pursues policies that would provide its domestic industries with the ability to outcompete rival firms. China’s state capitalism model with its industrial policies favouring state-owned enterprises via subsidies has become the bane of many foreign competing firms pointing to market distortions and increasing operating costs across various service lines. The threat posed by China’s economic model has stimulated U.S. bipartisan support for a comprehensive manufacturing bill – the CHIPS and Science Act – designed to bolster America’s manufacturing industry and technological edge through subsidies and research and development funding as part of a long-term strategy to acquire strategic independence.

Along the commercial front, the series of tariffs levied by the Trump administration responsible for initiating a trade war with China in 2018 was ostensibly an attempt to reduce the United States’ trade deficit and address several grievances. While trade wars are often depicted as zero-sum games, “the truth is”, as the economist Paul Krugman put it, “trade wars are bad, and almost everyone ends up losing economically.” The Trump administration’s tariffs affected not only Chinese industries but also those of American allies like Japan and the European Union – straining relations, prompting retaliatory tariffs, and leading to a restructuring of global supply chains. Shortly after taking office, President Biden and his administration reversed tariffs adversely affecting its allies, but maintained or extended existing tariffs placed on Chinese imports in response to China’s failure to meet commitments that had been agreed upon in a deal signed in January 2020 – the Phase One Trade Agreement – and to threatening economic practices.

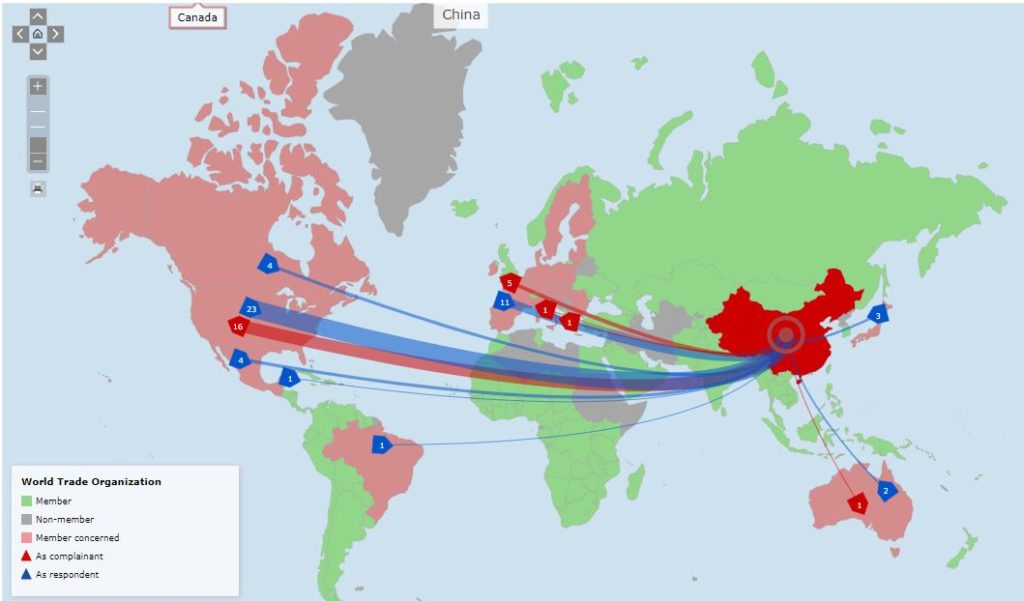

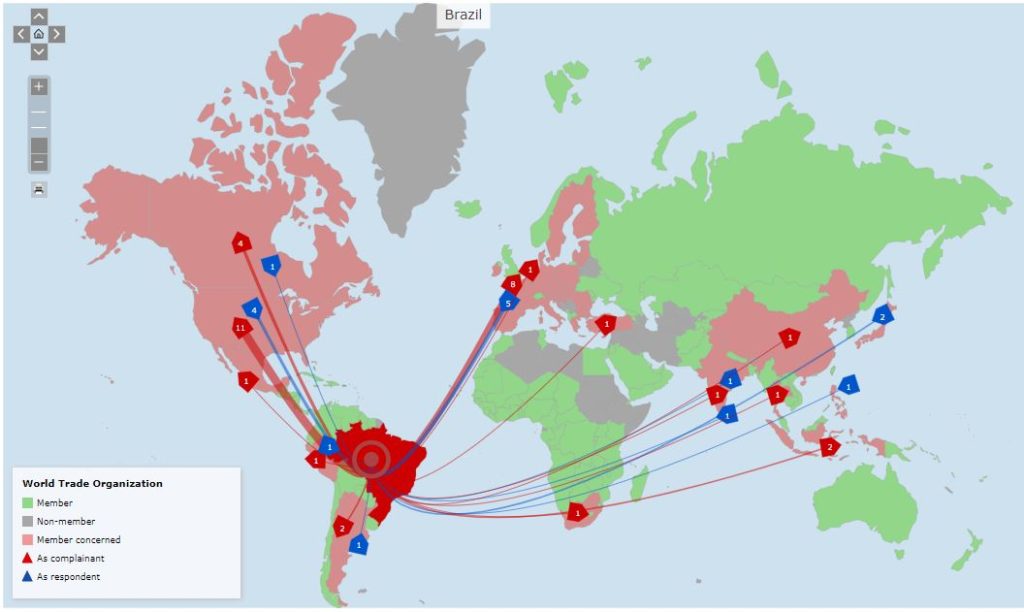

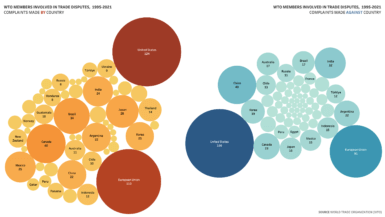

The rise of geoeconomics has posed challenges and limitations to the Bretton Woods Institutions, which have served as the bastions of the international rules-based system. For example, since 2019, the dispute settlement mechanism of the World Trade Organization (WTO) – arguably its most important function – has been crippled by the vetoing of proposed adjudicator appointments to the Appellate Body, thereby limiting its authority and increasing the chances of escalation.

WTO members involved in trade disputes, 1995-2021

WTO members involved in trade disputes, 1995-2021The growing popularity of preferential and regional trade agreements such as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement and Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement have been a response to increased interest in regionalisation, the WTO’s relative sluggishness to rally consensus around new rules, and multilateral deadlock. These bilateral and plurilateral agreements can address multiple provisions around commercial aspects such as regulations and investments while aligning policies around issues like climate and sustainability among signatories in a more expedient manner.

Towards a New Geoeconomic Order?

The multiple decades of growth and integration accelerated by globalisation’s latest iteration during the Pax Americana period opened up new venues for global players like China and the European Union to exert their economic power in a way that would facilitate the pursuit of national interests. As recent political developments have shown, confrontations between the United States and China have led to a rise in geoeconomic policies designed to either expand economic and political power or counter rival political influence. China’s prominence as a rising power and geoeconomic powerhouse has encouraged greater cooperation between the United States, the European Union, and other allies to limit their geopolitical dependency and halt its expansive growth.

Military strength remains a crucial component for security and deterrence; however, it has now become overlaid with economic policy instruments to effectively achieve multifaceted strategic objectives. The frequency of commercial clashes and disputes between large economies making headlines in recent years can be attributed to these policy choices; however, competition and coercion also express themselves in other ways. Economic sanctions remain the longstanding tool for countries seeking to shape political behaviour by applying pressure on key industries. This can be seen in Western powers’ sanctions against Russia after its annexation of Crimea and the recent invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s retaliatory cuts in energy supplies to Europe, or the Biden administration’s export controls on semiconductor technology moving into China to stymie its military and economic capabilities.We are now at a crossroads where conformations of major powers are aligning strategic policies and weaponising their capabilities to counter opposing forces

We are now at a crossroads where conformations of major powers are aligning strategic policies and weaponising their capabilities to counter opposing forces and achieve economic and political dominance, security, and influence. The ability to sway governments, set global agendas, and strengthen or establish new institutions upholding norms favourable to one’s national interests has become key to most major players. While it is too soon to say what the future of geoeconomics will look like, one can expect a continued rise in the importance of resources (e.g., energy commodities and raw materials), advanced technologies, economic tools, and policy instruments in driving competition, bargaining, coercion, and cooperation.

DEFINITIONS related to sanctions and economic warfare

Economic and financial sanctions are enforcement actions taken by a country or a group of countries against a targeted state, group, or individual that has been found in non-compliance with existing international law, treaty obligations and customary rules. They can take many forms, like restrictions on commercial or financial transactions, asset freezes, travel bans, or the withholding of economic and technical assistance. They pursue a variety of social, commercial and/or political objectives depending on the kind of violations committed by the target group or state. Usually, they are supposed to coerce targets of sanctions into compliant behaviour, but often, they serve to deter third countries from pursuing similar violations of international law commitments. As an enforcement action, sanctions are supposed to refer to a specific violation of existing law, rather than constitute a purely political measure.

An embargo is the partial or complete proscription of commerce with a particular country or a group of countries. It entails the ban of imports or exports of certain items, or whole sectors, or all products from or to a specified country. One of the most famous illustrations is the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 in retaliation to Western support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. As a barrier to trade, an embargo should not be confused with a military blockade, although enforcement of the embargo could escalate into a military intervention. In contrast to sanctions, which are conceived as enforcement actions, an alliance of states can decide to erect an embargo based on political reasons, for instance, to help allies involved in a conflict by weakening the economy of inimical states.

Sanctions have been used to advance a range of foreign policy goals, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, nonproliferation, democracy and human rights promotion, conflict resolution, and cybersecurity. Sanctions, while a form of intervention, are generally viewed as a lower-cost, lower-risk course of action between diplomacy and war. Still, the costs of sanctions are harder to measure, and human costs can be very high, especially when a whole economy is sanctioned, as in the case of “comprehensive sanctions” against Iraq in the 1990s, or when the whole financial system of a country is crippled, as in the case of “massified” targeted financial sanctions against Iran in the early 2010s.

As the UN’s principal crisis-management body, the Security Council (UNSC) may respond to global threats by imposing sanctions against states and nonstate groups who are found in non-compliance of international law. Sanctions resolutions must pass the fifteen-member council by a majority vote and without a veto from any of the five permanent members: the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The most common types of UN sanctions, which are binding for all member states, are asset freezes, travel bans, and arms embargoes. UN sanctions regimes are typically managed by a special committee and a monitoring group. The global police agency INTERPOL assists some sanctions committees, but the UN has no independent means of enforcement and relies on member states, many of which have limited resources and little political incentive to prosecute noncompliance. Still, the private sector, and especially banking institutions, have come to integrate the names of front companies found in the reports of UN monitoring groups that document evasion practices of specific UNSC sanction regimes, which demonstrates the centrality attained by the UNSC in the management of sanctions. Prior to 1990, the UNSC had imposed sanctions against just two states: Southern Rhodesia (1966) and South Africa (1977), but there has been a long history of sanctions by the League of Nations, of which the UN is the successor organisation.

The European Union imposes sanctions, known more commonly in the 28-member bloc as “restrictive measures”, as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. Because the EU lacks a joint military force, many European leaders consider sanctions the bloc’s most powerful foreign policy tool, based on the experience attained during the early 2010s in the nuclear negotiation with Iran that lead to the signature of the JCPOA in 2015. Sanctions policies must receive unanimous consent from member states in the Council of the European Union, the body that represents EU leaders. Since its inception in 1992, the EU has levied sanctions more than 30 times (in addition to those mandated by the UN). Analysts say the “massified” targeted sanctions the EU bloc imposed on Iran in 2012 – which it lifted in 2015 as part of the Iran nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) – marked a turning point for the EU, which had previously sought to limit sanctions to specific individuals or companies.

The United States uses economic and financial sanctions more than any other country. Sanctions policy may originate in either the executive or legislative branch. Presidents typically launch the process by issuing an executive order (EO) that declares a national emergency in response to an “unusual and extraordinary” foreign threat, for example, “the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons” (EO 12938) or “the actions and policies of the Government of the Russian Federation with respect to Ukraine” (EO 13661). Many US sanctions regimes are administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), located in the Department of the Treasury: OFAC is often considered an all-powerful organisation, as it is in charge of sanctions designations, sanctions exemptions and humanitarian licenses, and examination of delisting requests.

Economic nationalism is an ideology that advocates bolstering and protecting national economies in an effort to countenance or counteract the effects of trade liberalisation and globalisation. It aims to maximise national self-reliance by reverting to elements of protectionism and mercantilism. Economic nationalism privileges state control and interventionism over market mechanisms, profit maximisation and growth. It typically restricts flows of labour, capital, goods and services through protectionist measures such as tariffs, investment controls or export restrictions.

Reshoring is the opposite of offshoring. It refers to companies repatriating “back home” parts or all of their supply chains components, including back-office, manufacturing, or R&D processes. Nearshoring and friendshoring obey a logic similar to reshoring, but instead of production and manufacturing being repatriated back to the “home country”, they are relocated to neighbouring (nearshoring) or allied countries (friendshoring).

Research Office, Geneva Graduated Institute. Questions largely inspired by the Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org.