Sanctions against Russia and the Role of the United Nations

The three-month period between the build-up of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border and the invasion in February 2022 gave Western countries time to build an informal coalition to impose deterrent measures against Russia. Not only is this coalition unusual for its high level of coordination, it is extraordinary in that it has been accompanied by a broad disengagement from Russia by civil society actors from across the world.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) was designed to prevent major powers from abandoning the organisation, as they had its predecessor, the League of Nations. Giving the veto to five permanent (or non-elected) members effectively removes them from consequences when their actions, or those of their client states, come under review. This means that globally binding resolutions imposing restrictive measures cannot be applied to the permanent members by the Security Council, since they will invariably veto them.

This does not mean, however, that the Security Council has no role. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been taken up in a number of special sessions of the Council over the past seven months. A recent UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution requires that countries using the veto must come before the UNGA to explain their rationale for the veto, and Russia complied with the measure.

The primary way in which UN organs such as the General Assembly and the Human Rights Council have expressed their concerns about the invasion has been through resolutions condemning Russia. The UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly – 141 to 5, with 35 abstentions – that Russia “immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders” on 2 March 2022. Later in the year, on 7 April, following alleged human rights atrocities in Bucha, the General Assembly voted to suspend Russia’s membership on the Human Rights Council, with a vote of 93 to 24, with 58 abstentions.

Informal Multilateralism

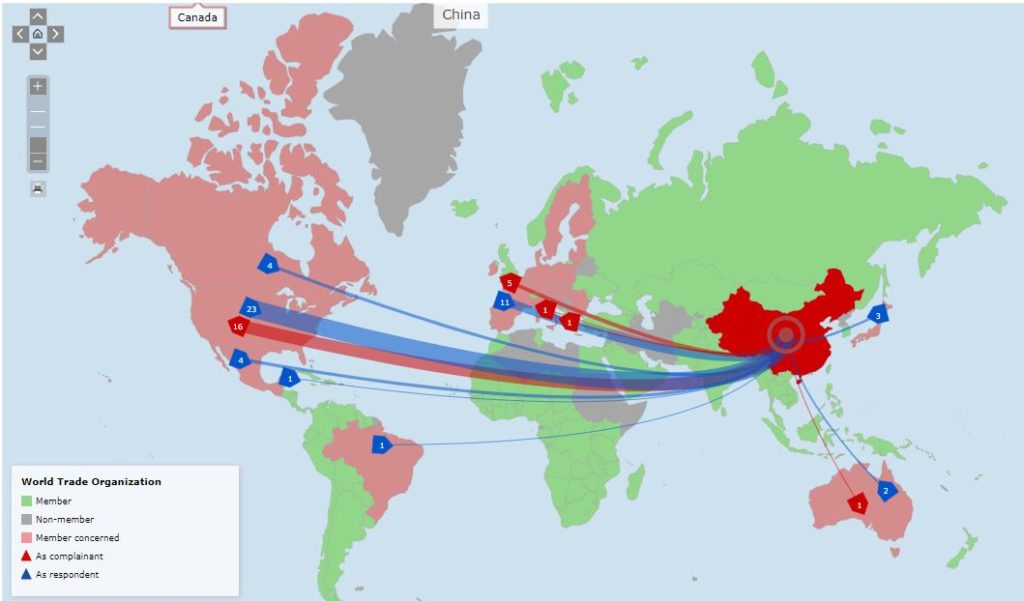

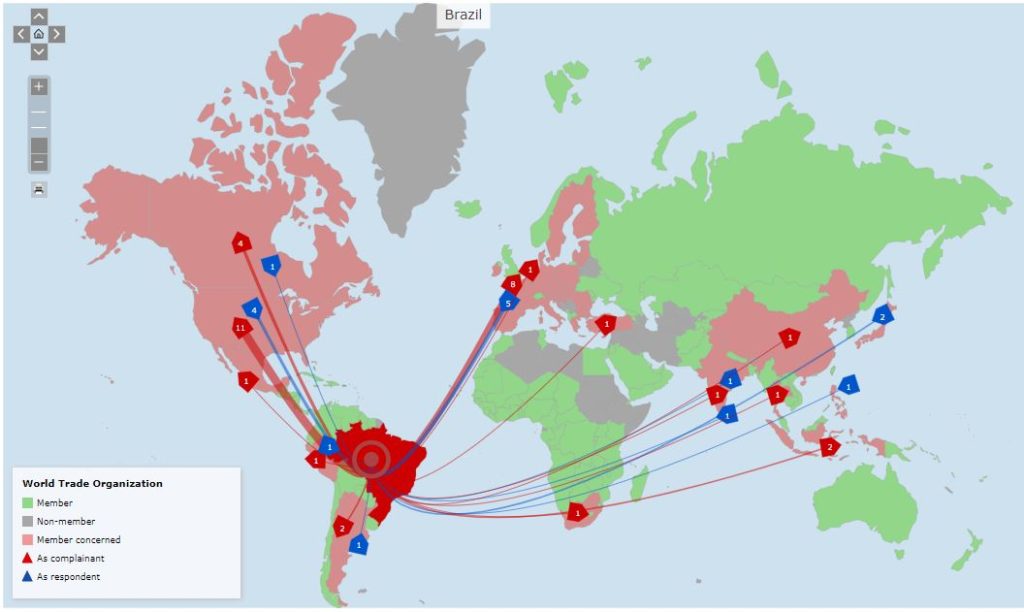

As a result of the UN’s inability to apply sanctions on permanent members of the Security Council, countries have for decades designed and imposed sanctions of their own, with varying degrees of coordination. The United States (US) has been the most active when it comes to imposing sanctions, adopting a large number of country and thematic sanctions regimes and making the largest number of individual designations (of individual persons and entities).

The European Union (EU) has developed its autonomous sanctions regimes significantly over the past three decades and currently has more sanctions regimes in place (but fewer individual designations) than the US. Other countries have joined in with their own sanctions regimes, including the United Kingdom (UK) – since Brexit –, Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea and others (including Switzerland), depending on the conflict. Imposing sanctions is not just a “Western” practice, however. Not only have Japan, South Korea and Singapore participated in applying sanctions on Russia, but Russia, China and India, not to mention regional organisations like the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), have a long history of using sanctions as an instrument of foreign policy or regional peace-making. They may declare their opposition to sanctions in general terms, but virtually everyone uses them.Imposing sanctions is not just a “Western” practice, however

The most robust informal coordination of sanctions to date preceded, and immediately followed, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Russia began amassing significant numbers of troops on the Ukrainian border in November 2021. That gave the US and Europe three months before the invasion to discuss and plan for coordinated intervention, should Russia proceed to attack Ukraine. Multilateral sanctions were explicitly threatened for months in an effort to deter Russia. They were not the only policy instruments being employed to deter Russia, however. An unusual amount of intelligence information was released to the public, and there were active efforts of diplomacy, particularly by France and Germany. The precise details of the threatened sanctions were kept ambiguous, in an effort to enhance their potential deterrent effect, but the multitrack effort to deter Russia did not prevent it from miscalculating and attacking Ukraine in the end.

UN SanctionsApp is an interactive analytical tool that can be used in real time by both scholars and policy practitioners who have an interest in examining, or who are working on designing and implementing, UN sanctions. UN SanctionsApp is managed and updated at the Global Governance Centre at the Graduate Institute in Geneva, Switzerland.

UN SanctionsApp is an interactive analytical tool that can be used in real time by both scholars and policy practitioners who have an interest in examining, or who are working on designing and implementing, UN sanctions. UN SanctionsApp is managed and updated at the Global Governance Centre at the Graduate Institute in Geneva, Switzerland.With more than three months before the invasion to consider restrictive measures, there was an unusual degree of planning and pre-coordination by the US, EU and UK. They were joined by other states concerned about the precedent being created by Russia, cumulatively involving countries with economies accounting for more than half of the world’s economic activity. There is variation, of course, in the specific measures being applied, their timing and sequencing, as well as in the lists of specific individuals and firms being targeted in different jurisdictions. Despite this variation, the current sanctions are the most extensive ever applied on Russia or on a country previously integrated as extensively as Russia into the global economy. That being said, there has been a great deal of hyperbole and misleading commentary in discussions of the sanctions on Russia.

Three Myths about the Sanctions on Russia

The first and most misleading myth is that the sanctions are “unprecedented” in content, scale, and scope. This suits the discourse of political leaders in the US and Europe, but there is nothing that has been imposed on Russia that has not been applied to other countries under sanctions. There are still many areas where trade with Russia is allowed. Banking channels have remained open, and despite its considerable efforts to reduce its energy dependence, Europe continues to buy more oil and gas from Russia than China and India (at least as of this writing). The UN sanctions on North Korea are more extensive in scope than the Russia sanctions, and Iran has been under more sweeping sanctions from the US, including the application and enforcement of secondary sanctions. What is unprecedented in the case of Russia, however, is the amount of voluntary disengagement from Russia by civil society actors across the globe, but that is another subject.

The second myth is to describe the sanctions as “economic warfare”. The war metaphor is over-used, as scholars analysing the “war on drugs” and the “war on terror” can attest. These were metaphorical wars, and describing the current sanctions on Russia as “economic warfare” does not add much insight to the analysis.Describing the current sanctions on Russia as “economic warfare” does not add much insight to the analysis The sanctions literature has long distinguished between economic sanctions and economic warfare. The countries currently sanctioning Russia are not in a declared war with Russia; they are applying restrictive measures to achieve political goals. In a declared war, industrial production of military equipment could be targeted and all trade with the adversary embargoed; that would be economic warfare.

The third myth relates to Switzerland. A recent article published in The Wilson Quarterly’s Summer 2022 issue repeats a common trope in many news commentaries that “even Switzerland, typically neutral in international disputes, agreed to impose similar sanctions to those levied by the European Union”. There is nothing new or extraordinary about Bern’s application of restrictive measures or alignment with the EU, as the leaders of Belarus and Myanmar know well. Switzerland has been applying restrictive measures in pursuit of Swiss foreign policy goals and coordinating closely with the EU for decades.

Conclusion

The UN has been engaged in normative signalling about violations of international law following Russia’s invasion, including by Secretary-General Guterres at this year’s General Assembly meeting. Other agencies of the UN have been actively involved in inspections of Ukraine’s nuclear facilities and providing humanitarian relief to those affected by the war. But when it comes to sanctions, the UN has been constrained by its institutional design. This has enabled informal multilateral action by a coalition of like-minded states. The variation in their specific measures will create avenues for evasion, but their informal multilateralism is a response to design features of the UN Charter itself.

DEFINITIONS related to sanctions and economic warfare

Economic and financial sanctions are enforcement actions taken by a country or a group of countries against a targeted state, group, or individual that has been found in non-compliance with existing international law, treaty obligations and customary rules. They can take many forms, like restrictions on commercial or financial transactions, asset freezes, travel bans, or the withholding of economic and technical assistance. They pursue a variety of social, commercial and/or political objectives depending on the kind of violations committed by the target group or state. Usually, they are supposed to coerce targets of sanctions into compliant behaviour, but often, they serve to deter third countries from pursuing similar violations of international law commitments. As an enforcement action, sanctions are supposed to refer to a specific violation of existing law, rather than constitute a purely political measure.

An embargo is the partial or complete proscription of commerce with a particular country or a group of countries. It entails the ban of imports or exports of certain items, or whole sectors, or all products from or to a specified country. One of the most famous illustrations is the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 in retaliation to Western support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. As a barrier to trade, an embargo should not be confused with a military blockade, although enforcement of the embargo could escalate into a military intervention. In contrast to sanctions, which are conceived as enforcement actions, an alliance of states can decide to erect an embargo based on political reasons, for instance, to help allies involved in a conflict by weakening the economy of inimical states.

Sanctions have been used to advance a range of foreign policy goals, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, nonproliferation, democracy and human rights promotion, conflict resolution, and cybersecurity. Sanctions, while a form of intervention, are generally viewed as a lower-cost, lower-risk course of action between diplomacy and war. Still, the costs of sanctions are harder to measure, and human costs can be very high, especially when a whole economy is sanctioned, as in the case of “comprehensive sanctions” against Iraq in the 1990s, or when the whole financial system of a country is crippled, as in the case of “massified” targeted financial sanctions against Iran in the early 2010s.

As the UN’s principal crisis-management body, the Security Council (UNSC) may respond to global threats by imposing sanctions against states and nonstate groups who are found in non-compliance of international law. Sanctions resolutions must pass the fifteen-member council by a majority vote and without a veto from any of the five permanent members: the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The most common types of UN sanctions, which are binding for all member states, are asset freezes, travel bans, and arms embargoes. UN sanctions regimes are typically managed by a special committee and a monitoring group. The global police agency INTERPOL assists some sanctions committees, but the UN has no independent means of enforcement and relies on member states, many of which have limited resources and little political incentive to prosecute noncompliance. Still, the private sector, and especially banking institutions, have come to integrate the names of front companies found in the reports of UN monitoring groups that document evasion practices of specific UNSC sanction regimes, which demonstrates the centrality attained by the UNSC in the management of sanctions. Prior to 1990, the UNSC had imposed sanctions against just two states: Southern Rhodesia (1966) and South Africa (1977), but there has been a long history of sanctions by the League of Nations, of which the UN is the successor organisation.

The European Union imposes sanctions, known more commonly in the 28-member bloc as “restrictive measures”, as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. Because the EU lacks a joint military force, many European leaders consider sanctions the bloc’s most powerful foreign policy tool, based on the experience attained during the early 2010s in the nuclear negotiation with Iran that lead to the signature of the JCPOA in 2015. Sanctions policies must receive unanimous consent from member states in the Council of the European Union, the body that represents EU leaders. Since its inception in 1992, the EU has levied sanctions more than 30 times (in addition to those mandated by the UN). Analysts say the “massified” targeted sanctions the EU bloc imposed on Iran in 2012 – which it lifted in 2015 as part of the Iran nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) – marked a turning point for the EU, which had previously sought to limit sanctions to specific individuals or companies.

The United States uses economic and financial sanctions more than any other country. Sanctions policy may originate in either the executive or legislative branch. Presidents typically launch the process by issuing an executive order (EO) that declares a national emergency in response to an “unusual and extraordinary” foreign threat, for example, “the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons” (EO 12938) or “the actions and policies of the Government of the Russian Federation with respect to Ukraine” (EO 13661). Many US sanctions regimes are administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), located in the Department of the Treasury: OFAC is often considered an all-powerful organisation, as it is in charge of sanctions designations, sanctions exemptions and humanitarian licenses, and examination of delisting requests.

Economic nationalism is an ideology that advocates bolstering and protecting national economies in an effort to countenance or counteract the effects of trade liberalisation and globalisation. It aims to maximise national self-reliance by reverting to elements of protectionism and mercantilism. Economic nationalism privileges state control and interventionism over market mechanisms, profit maximisation and growth. It typically restricts flows of labour, capital, goods and services through protectionist measures such as tariffs, investment controls or export restrictions.

Reshoring is the opposite of offshoring. It refers to companies repatriating “back home” parts or all of their supply chains components, including back-office, manufacturing, or R&D processes. Nearshoring and friendshoring obey a logic similar to reshoring, but instead of production and manufacturing being repatriated back to the “home country”, they are relocated to neighbouring (nearshoring) or allied countries (friendshoring).

Research Office, Geneva Graduated Institute. Questions largely inspired by the Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org.