A Renewed Neocolonial Scramble for Resources?

Commodity price volatility and supply disruptions resulting from the war in Ukraine have had severe consequences for food and energy security around the world. This uncertain environment also has also made it more difficult for commodity-exporting countries to implement sound fiscal and budgetary policies. In this context, many commodity-exporting developing countries are once again struggling to break out of a cycle of neocolonial exploitation.

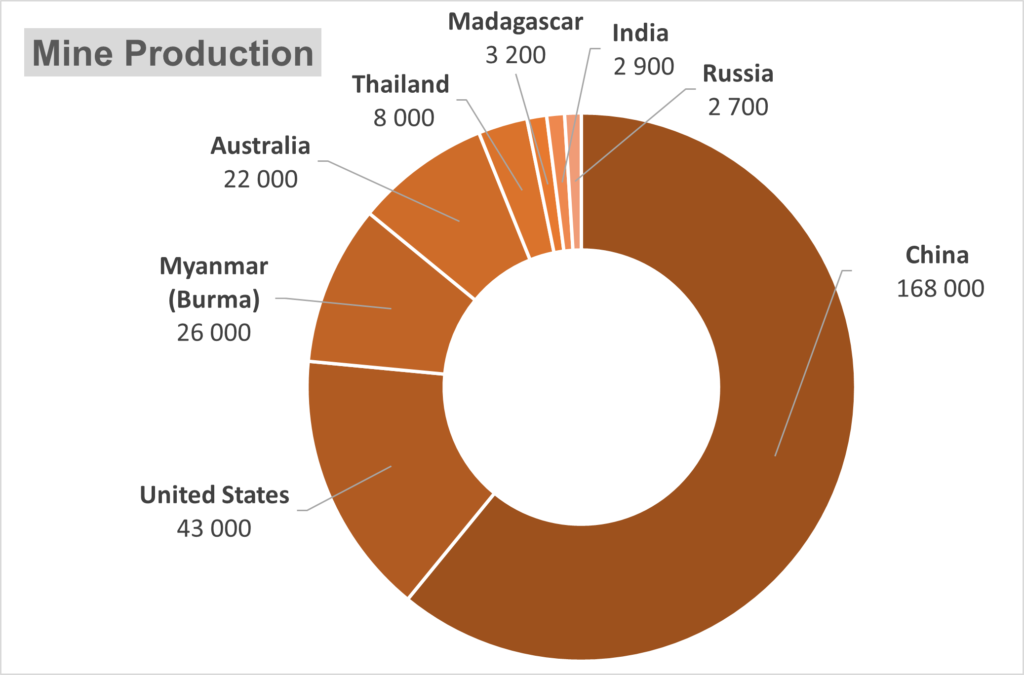

The third great scramble for natural resources is underway to power the green economy and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Investing in renewable energy and e-vehicles entails a rush on cobalt, lithium, rare-earth and other strategic minerals. With population growth and diet diversification in South Asia and Africa, we are also witnessing a steady growth in demand for agricultural products. Renewed great power competition, finally, has triggered a return of resource nationalism, pipeline politics and the securitisation of critical supplies.

The first global scramble for resources saw early industrial powers such as the Netherlands, Great-Britain and France carving up foreign territories for colonial exploitation. The Cold War gave rise to the second great scramble whereby the East and the West competed to secure political and trading allegiances with newly independent states whose economies have often been heavily reliant on commodity exports. As a result, many emerging economies are heavily skewed toward commodity exports and suffer from price and revenue volatility, a lack of economic diversification, rentier states and violent rent-seeking and environmental degradation, i.e., the resource curse syndrome.

Developing countries remain a vital source for imports of strategic commodities

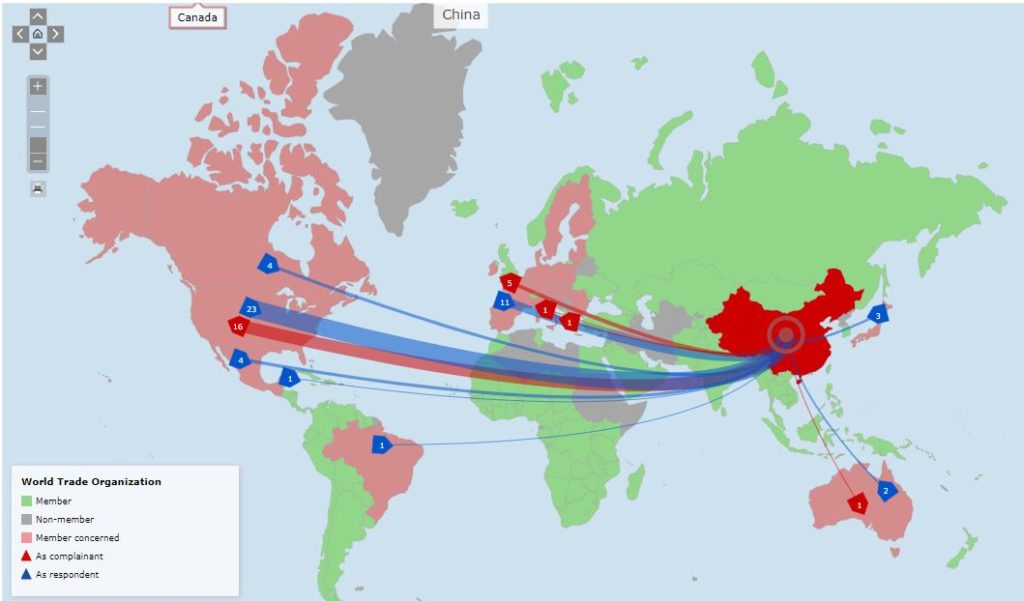

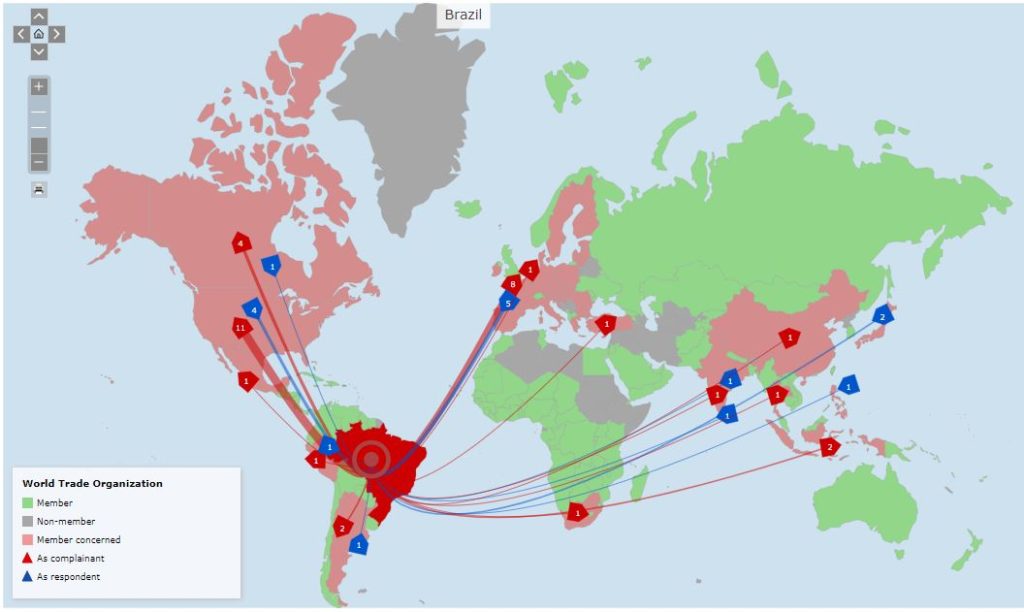

What is different today? While the global impetus towards greening the economy and sustained growth in large emerging economies are new, the ensuing scramble for strategic commodities sourced in poorer countries is not.Will commodity exporters again be forced to take side in the face of renewed great power competition and the fragmentation of global supply chains and financial markets? Are we therefore simply witnessing a form of veiled neocolonialism whereby stronger economic powers continue to exploit resource-rich developing countries? Will commodity exporters again be forced to take side in the face of renewed great power competition and the fragmentation of global supply chains and financial markets? To address such questions, we draw insights from a six-year research project on commodity-trade-related illicit financial flows. Our research investigates how resource-rich developing countries can reduce the erosion of their natural resource wealth accruing from undervalued commodity exports and enhance their capacities to mobilise the domestic revenues required to invest in sustainable development.

We study commodity trade between resource-rich countries in Africa and Asia and trading hubs like Geneva, Singapore or Dubai.

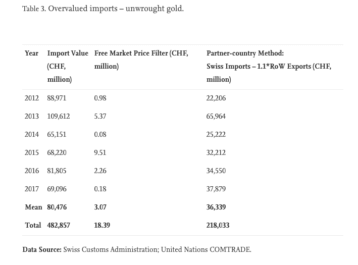

Overall, there remain significant weaknesses in trade governance and regulatory oversight. As an example, we find that a share of gold exports from Ghana to major trading hubs is under-priced, resulting in a significant loss of tax revenue for the African country. Similarly, in Laos, foreign mining interests have exploited most remaining metal and mineral deposits for economic powerhouses in the region with little transparency over export valuation and royalties paid. Commodity exporters too often lack the capacity to effectively deal with complex transfer pricing issues and properly value trade transactions between affiliates of the same multinational group.

Tax base erosion is a major issue for commodity-exporting countries

In major trading and financial hubs, importers are often exempt from detailed reporting on transfer prices and benefit from tax incentives that may encourage illicit financial flows. Typically, corporate tax ranges between 10% and 15% in trading and financial hubs compared to 25–35% in resource-rich developing countries.Weak reporting requirements and monitoring capacities aggravate tax-base erosion in commodity-exporting countries Weak reporting requirements and monitoring capacities aggravate tax-base erosion in commodity-exporting countries, replicating a form of neocolonial exploitation whereby citizens do not draw benefit from their natural wealth. Global tax reforms envisaged under the OECD/G20 to levy fair taxes in consumer countries may be appropriate to deal with tech companies and the e-economy but not with the commodity sector, where the issue is taxing where extraction rather than consumption takes place. Based on our research findings, we propose to introduce simplified taxation methods that are suited for countries with weaker administrative capabilities. For instance, relevant global reference prices that are readily available for many commodities could be used to value trade in natural resources.

At the global level, value chain disruptions and high price volatility hinder the capacity of poorer commodity-dependent states to implement sound fiscal and budgetary policies. As illustrated by the knock-on effects of the conflict in Ukraine, commodity price volatility and supply disruptions have dire consequences in terms of global food and energy security. In addition, these states have a weaker ability to navigate an increasing number of sanction regimes that, at times, bar the use of the usual services offered by a Western-dominated financial system. They may also have a weaker ability to resort to alternative financial networks, such as China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payments System. Competing financial systems may in turn spur increased trade frictions by increasing compliance requirements and operational costs that disproportionately penalise traders in poor countries. In this context, competing grand schemes like China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the G7-led Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment may offer additional development finance and trade opportunities to resource-rich developing countries but also come with renewed risks of economic and political dependency.

Poorer countries need multilateral fiscal arrangements if they are to benefit fully from their natural resources

To conclude, the scramble for resources will not benefit people in poorer resource-rich countries without multilateral arrangements that strengthen global tax governance and effectively curb illicit financial flows. For now, trends point towards a hardening of competing spheres of influence vying to control strategic resources and trading routes. To paraphrase an apocryphal quote, “We live in interesting times.” Yet those who are least equipped to enjoy them will once again be the ones worst affected, unless we collectively chart a different course. Our research project has identified and promotes specific proposals to this end.

DEFINITIONS related to sanctions and economic warfare

Economic and financial sanctions are enforcement actions taken by a country or a group of countries against a targeted state, group, or individual that has been found in non-compliance with existing international law, treaty obligations and customary rules. They can take many forms, like restrictions on commercial or financial transactions, asset freezes, travel bans, or the withholding of economic and technical assistance. They pursue a variety of social, commercial and/or political objectives depending on the kind of violations committed by the target group or state. Usually, they are supposed to coerce targets of sanctions into compliant behaviour, but often, they serve to deter third countries from pursuing similar violations of international law commitments. As an enforcement action, sanctions are supposed to refer to a specific violation of existing law, rather than constitute a purely political measure.

An embargo is the partial or complete proscription of commerce with a particular country or a group of countries. It entails the ban of imports or exports of certain items, or whole sectors, or all products from or to a specified country. One of the most famous illustrations is the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 in retaliation to Western support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. As a barrier to trade, an embargo should not be confused with a military blockade, although enforcement of the embargo could escalate into a military intervention. In contrast to sanctions, which are conceived as enforcement actions, an alliance of states can decide to erect an embargo based on political reasons, for instance, to help allies involved in a conflict by weakening the economy of inimical states.

Sanctions have been used to advance a range of foreign policy goals, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, nonproliferation, democracy and human rights promotion, conflict resolution, and cybersecurity. Sanctions, while a form of intervention, are generally viewed as a lower-cost, lower-risk course of action between diplomacy and war. Still, the costs of sanctions are harder to measure, and human costs can be very high, especially when a whole economy is sanctioned, as in the case of “comprehensive sanctions” against Iraq in the 1990s, or when the whole financial system of a country is crippled, as in the case of “massified” targeted financial sanctions against Iran in the early 2010s.

As the UN’s principal crisis-management body, the Security Council (UNSC) may respond to global threats by imposing sanctions against states and nonstate groups who are found in non-compliance of international law. Sanctions resolutions must pass the fifteen-member council by a majority vote and without a veto from any of the five permanent members: the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The most common types of UN sanctions, which are binding for all member states, are asset freezes, travel bans, and arms embargoes. UN sanctions regimes are typically managed by a special committee and a monitoring group. The global police agency INTERPOL assists some sanctions committees, but the UN has no independent means of enforcement and relies on member states, many of which have limited resources and little political incentive to prosecute noncompliance. Still, the private sector, and especially banking institutions, have come to integrate the names of front companies found in the reports of UN monitoring groups that document evasion practices of specific UNSC sanction regimes, which demonstrates the centrality attained by the UNSC in the management of sanctions. Prior to 1990, the UNSC had imposed sanctions against just two states: Southern Rhodesia (1966) and South Africa (1977), but there has been a long history of sanctions by the League of Nations, of which the UN is the successor organisation.

The European Union imposes sanctions, known more commonly in the 28-member bloc as “restrictive measures”, as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. Because the EU lacks a joint military force, many European leaders consider sanctions the bloc’s most powerful foreign policy tool, based on the experience attained during the early 2010s in the nuclear negotiation with Iran that lead to the signature of the JCPOA in 2015. Sanctions policies must receive unanimous consent from member states in the Council of the European Union, the body that represents EU leaders. Since its inception in 1992, the EU has levied sanctions more than 30 times (in addition to those mandated by the UN). Analysts say the “massified” targeted sanctions the EU bloc imposed on Iran in 2012 – which it lifted in 2015 as part of the Iran nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) – marked a turning point for the EU, which had previously sought to limit sanctions to specific individuals or companies.

The United States uses economic and financial sanctions more than any other country. Sanctions policy may originate in either the executive or legislative branch. Presidents typically launch the process by issuing an executive order (EO) that declares a national emergency in response to an “unusual and extraordinary” foreign threat, for example, “the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons” (EO 12938) or “the actions and policies of the Government of the Russian Federation with respect to Ukraine” (EO 13661). Many US sanctions regimes are administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), located in the Department of the Treasury: OFAC is often considered an all-powerful organisation, as it is in charge of sanctions designations, sanctions exemptions and humanitarian licenses, and examination of delisting requests.

Economic nationalism is an ideology that advocates bolstering and protecting national economies in an effort to countenance or counteract the effects of trade liberalisation and globalisation. It aims to maximise national self-reliance by reverting to elements of protectionism and mercantilism. Economic nationalism privileges state control and interventionism over market mechanisms, profit maximisation and growth. It typically restricts flows of labour, capital, goods and services through protectionist measures such as tariffs, investment controls or export restrictions.

Reshoring is the opposite of offshoring. It refers to companies repatriating “back home” parts or all of their supply chains components, including back-office, manufacturing, or R&D processes. Nearshoring and friendshoring obey a logic similar to reshoring, but instead of production and manufacturing being repatriated back to the “home country”, they are relocated to neighbouring (nearshoring) or allied countries (friendshoring).

Research Office, Geneva Graduated Institute. Questions largely inspired by the Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org.