Risky Interdependence: The Impact of Geoeconomics on Trade Policy

In an attempt to level the economic playing field, and in response to urgent geopolitical threats like the Russian war in Ukraine, Western countries have begun to adopt a more unilateral approach to international economic relations. Even the EU – despite its propensity for multilateralism – has resorted to a number of unilateral measures, including both export controls and support for key domestic industries.

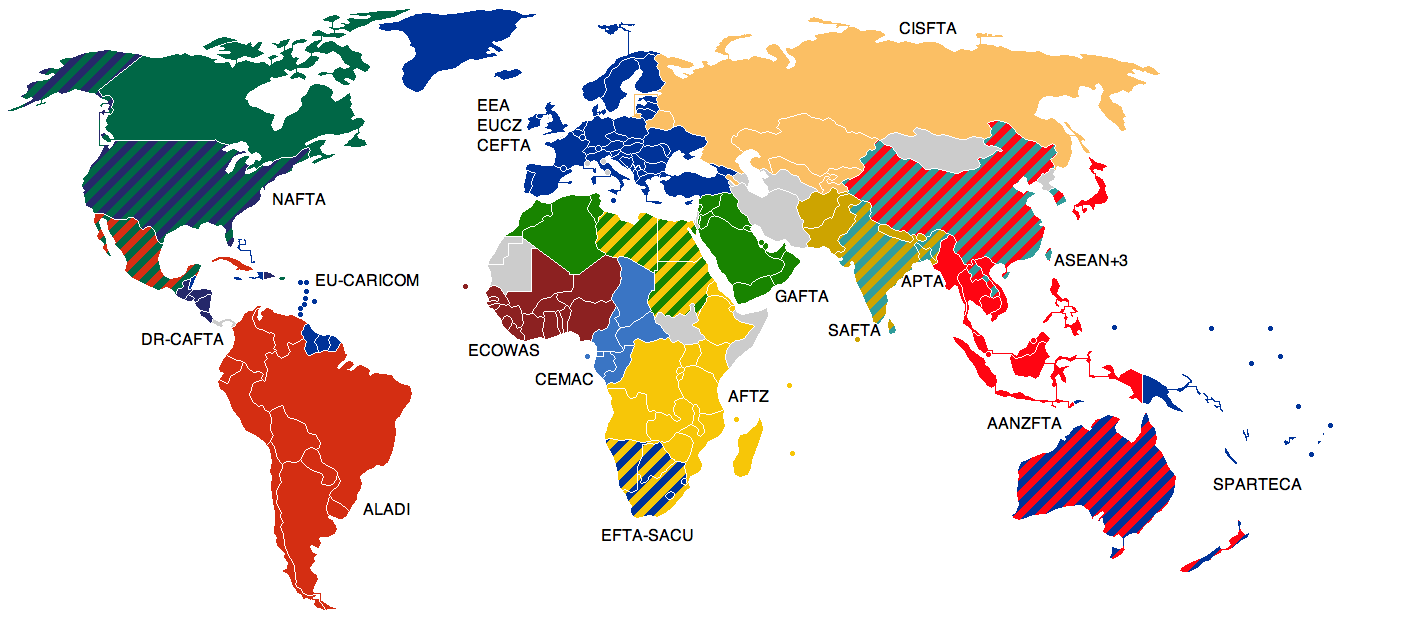

Until recently, cost efficiency was the main driver of international trade. Firms scoured the globe for cheap inputs and production sites. Driven by profit maximisation, they set up global value chains connecting friendly and not-so-friendly countries. Underlying fears of ideological differences, conventional thinking held, would be flattened over time, while “interdependence” would gradually make major frictions, let alone military conflict, impossible or too costly. Facilitated by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and free trade agreements, this latest phase of “globalisation” climaxed roughly between 1990 and 2015. It was characterised by unseen (though not always equally distributed) levels of prosperity, lifting millions of people out of poverty.

Four key factors, however, changed this propitious outlook. Two are structural: (1) competition with communist China’s “state capitalism”; (2) climate change and other sustainability imperatives, including worker rights. Two are, hopefully, more transient: (1) the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Together, these factors constituted a wake-up call signalling that “interdependence” also bears risks and that it may be “weaponised” in contexts of unfair competition (economic, environmental or social), supply shortages (be it of protective gear or natural gas), security threats or sanction regimes.

National self-sufficiency is rarely an adequate response to geopolitical risks

“Interdependence” bears risks and may be “weaponised” in contexts of unfair competition, supply shortages, security threats or sanction regimes How are nations responding to these new realities? One knee-jerk reaction is, not surprisingly, economic nationalism and calls for reshoring and self-sufficiency. Self-sufficiency, however, would be a very costly, if not impractical solution (especially for smaller countries). And even then, success in crisis would be far from guaranteed (what if the “national champion” producing masks has a supply problem?).

A more nuanced reaction focuses on diversification and resilience, and on making supply chains more secure and sustainable. How does this reflect on the WTO and trade agreements? At the WTO, multilateral agreement has become excruciatingly difficult. Positive outcomes at the WTO’s Ministerial Conference in June 2022 did, however, illustrate that it is not impossible. Yet, rather than further “liberalising” trade, the focus is on “managing” trade and its impacts: new rules on fisheries subsidies, incremental solutions on pandemic response and food security.

Cooperation agreements now often also cover factors such as the security of supply chains

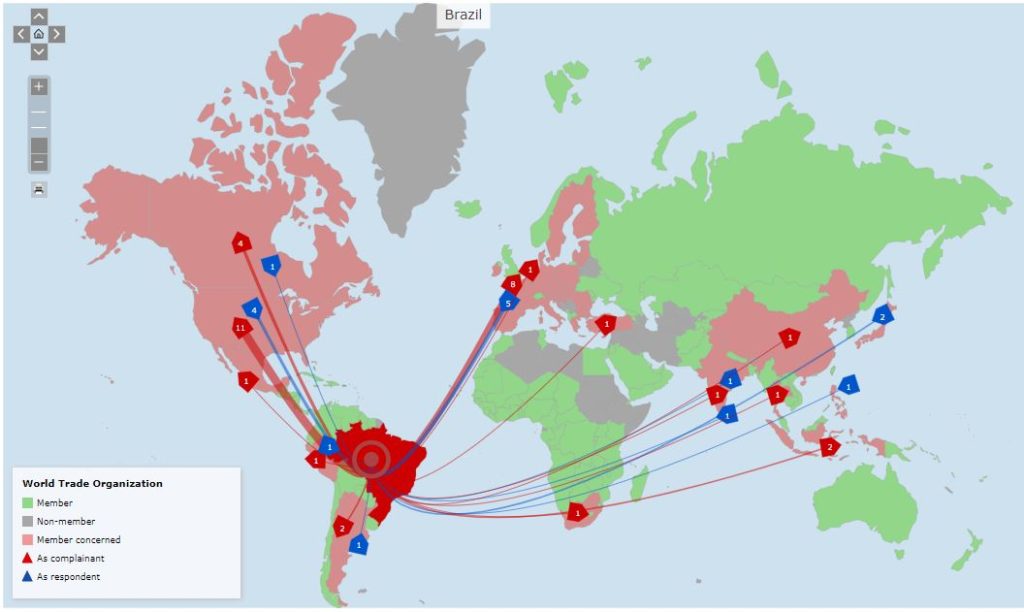

What about free trade agreements (FTAs)? The European Union (EU) interprets the need for “diversification” as a clarion call for more and deeper FTAs. In recent months, the EU concluded an FTA with New Zealand and started FTA negotiations with India. The United States (US), in contrast, is moving away from traditional FTAs with market access as the goal. It embarked instead on amorphous new frameworks of cooperation and exchange such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) or the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC). Here, the focus is on things like compatibility of standards, secure supply chains and clean energy. Instead of a binding treaty, output derives from ongoing working groups. Free trade and efficiency take a backseat. Top of mind are resilient supply chains and a cleaner, fairer economy, coordinated between countries that share similar values (“friend-shoring” rather than off-shoring to the cheapest bidder).

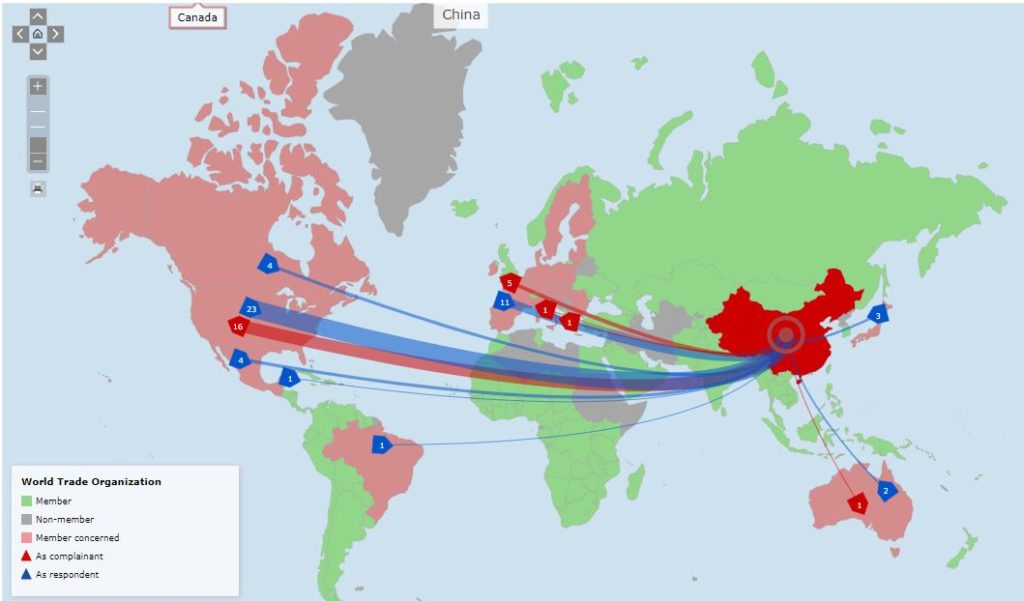

The most tangible response has, however, come from domestic trade policy. Not surprisingly, the US has utilised its economic power and interconnectedness to impose crippling sanctions and export controls on both China and Russia. It is also offering massive support to boost key domestic industries such as semiconductors (CHIPS Act) and electric vehicles (Inflation Reduction Act).

The response from the EU has been somewhat more surprising. Naturally inclined towards multilateral cooperation, the EU has instead intervened with a wide-ranging list of “unilateral” instruments. Besides sanctions on Russia, the EU has adopted or proposed new tools to (1) respond to geopolitical challenges, e.g. foreign investment screening, enhanced export controls and a new anti-coercion instrument, (2) level the economic playing field, e.g. a new foreign subsidy instrument and international procurement initiative, and (3) address “imported” sustainability problems via e.g. a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), deforestation and forced labour initiatives and a new directive imposing corporate sustainability due diligence. Here as well, the focus is not so much on free trade and market access, but on resilience, security, reciprocity and sustainability. Rather than global “value” chains, centred on efficiency, what may emerge are global “values” chains cemented between like-minded countries who feel they can trust each other.When interested in bold, new initiatives on trade, in response to the ongoing, multi-faceted crisis, turn to Washington DC and, especially, Brussels; not Geneva

This systemic gear-shifting by the EU from multilateral cooperation (where progress has stalled) to constructing a toolbox of unilateral interventions (a more “assertive” and “autonomous” trade policy) is no doubt of historical importance. The question remains how other countries will react, and especially whether it will be a stimulus for more international cooperation or rather a contribution to more economic and regulatory fragmentation. Another open question is whether these new EU instruments will actually be effective or remain “paper tigers” with high compliance costs for firms (especially EU firms) without tangible impact on the ground.

In any event, when interested in bold, new initiatives on trade in response to the ongoing, multifaceted crisis, turn to Washington DC and, especially, Brussels; not Geneva.

DEFINITIONS related to sanctions and economic warfare

Economic and financial sanctions are enforcement actions taken by a country or a group of countries against a targeted state, group, or individual that has been found in non-compliance with existing international law, treaty obligations and customary rules. They can take many forms, like restrictions on commercial or financial transactions, asset freezes, travel bans, or the withholding of economic and technical assistance. They pursue a variety of social, commercial and/or political objectives depending on the kind of violations committed by the target group or state. Usually, they are supposed to coerce targets of sanctions into compliant behaviour, but often, they serve to deter third countries from pursuing similar violations of international law commitments. As an enforcement action, sanctions are supposed to refer to a specific violation of existing law, rather than constitute a purely political measure.

An embargo is the partial or complete proscription of commerce with a particular country or a group of countries. It entails the ban of imports or exports of certain items, or whole sectors, or all products from or to a specified country. One of the most famous illustrations is the oil embargo imposed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 in retaliation to Western support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. As a barrier to trade, an embargo should not be confused with a military blockade, although enforcement of the embargo could escalate into a military intervention. In contrast to sanctions, which are conceived as enforcement actions, an alliance of states can decide to erect an embargo based on political reasons, for instance, to help allies involved in a conflict by weakening the economy of inimical states.

Sanctions have been used to advance a range of foreign policy goals, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, nonproliferation, democracy and human rights promotion, conflict resolution, and cybersecurity. Sanctions, while a form of intervention, are generally viewed as a lower-cost, lower-risk course of action between diplomacy and war. Still, the costs of sanctions are harder to measure, and human costs can be very high, especially when a whole economy is sanctioned, as in the case of “comprehensive sanctions” against Iraq in the 1990s, or when the whole financial system of a country is crippled, as in the case of “massified” targeted financial sanctions against Iran in the early 2010s.

As the UN’s principal crisis-management body, the Security Council (UNSC) may respond to global threats by imposing sanctions against states and nonstate groups who are found in non-compliance of international law. Sanctions resolutions must pass the fifteen-member council by a majority vote and without a veto from any of the five permanent members: the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The most common types of UN sanctions, which are binding for all member states, are asset freezes, travel bans, and arms embargoes. UN sanctions regimes are typically managed by a special committee and a monitoring group. The global police agency INTERPOL assists some sanctions committees, but the UN has no independent means of enforcement and relies on member states, many of which have limited resources and little political incentive to prosecute noncompliance. Still, the private sector, and especially banking institutions, have come to integrate the names of front companies found in the reports of UN monitoring groups that document evasion practices of specific UNSC sanction regimes, which demonstrates the centrality attained by the UNSC in the management of sanctions. Prior to 1990, the UNSC had imposed sanctions against just two states: Southern Rhodesia (1966) and South Africa (1977), but there has been a long history of sanctions by the League of Nations, of which the UN is the successor organisation.

The European Union imposes sanctions, known more commonly in the 28-member bloc as “restrictive measures”, as part of its Common Foreign and Security Policy. Because the EU lacks a joint military force, many European leaders consider sanctions the bloc’s most powerful foreign policy tool, based on the experience attained during the early 2010s in the nuclear negotiation with Iran that lead to the signature of the JCPOA in 2015. Sanctions policies must receive unanimous consent from member states in the Council of the European Union, the body that represents EU leaders. Since its inception in 1992, the EU has levied sanctions more than 30 times (in addition to those mandated by the UN). Analysts say the “massified” targeted sanctions the EU bloc imposed on Iran in 2012 – which it lifted in 2015 as part of the Iran nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) – marked a turning point for the EU, which had previously sought to limit sanctions to specific individuals or companies.

The United States uses economic and financial sanctions more than any other country. Sanctions policy may originate in either the executive or legislative branch. Presidents typically launch the process by issuing an executive order (EO) that declares a national emergency in response to an “unusual and extraordinary” foreign threat, for example, “the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons” (EO 12938) or “the actions and policies of the Government of the Russian Federation with respect to Ukraine” (EO 13661). Many US sanctions regimes are administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), located in the Department of the Treasury: OFAC is often considered an all-powerful organisation, as it is in charge of sanctions designations, sanctions exemptions and humanitarian licenses, and examination of delisting requests.

Economic nationalism is an ideology that advocates bolstering and protecting national economies in an effort to countenance or counteract the effects of trade liberalisation and globalisation. It aims to maximise national self-reliance by reverting to elements of protectionism and mercantilism. Economic nationalism privileges state control and interventionism over market mechanisms, profit maximisation and growth. It typically restricts flows of labour, capital, goods and services through protectionist measures such as tariffs, investment controls or export restrictions.

Reshoring is the opposite of offshoring. It refers to companies repatriating “back home” parts or all of their supply chains components, including back-office, manufacturing, or R&D processes. Nearshoring and friendshoring obey a logic similar to reshoring, but instead of production and manufacturing being repatriated back to the “home country”, they are relocated to neighbouring (nearshoring) or allied countries (friendshoring).

Research Office, Geneva Graduated Institute. Questions largely inspired by the Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org.