Africa: Violent Pasts and Other Futures

https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-x4pv-6a94Violent pasts imperil the future. But they may also be the means of building one.

“Remembering with the future in mind,’ as the South African scholar Bernard Lategan has urged, is a difficult thing to do. Memories of violence seem only to weigh down, and never uplift; to divide, not to unite. Translating from memory to history is no less uncomfortable. Histories of violence in Africa risk flirting with that most destructive of caricatures, that all there is to life in Africa is death. What can histories of violence offer for the future, beyond reminding us of the worst of the past?

The thing that matters about violent pasts is that they are never truly past. They live in the present, entangled with the future. We do not ‘move on’ – not completely, not all at once, not at the same speed, some of us not at all. Pain, grief and fear shape lives that have known suffering. Both anxiety and anger can propel repetition, the past revolving in cycles, alternations and escalations. The damage caused by acts and regimes of violence forms the rubble from which a future must be built. Speaking about a violent past does not liberate us from it; neither does ignoring it.

On one level, histories of violence press the question of responsibility. This is more than simple blame: how can we talk of justice today, or of a more just tomorrow, if we do not ask ourselves who bears responsibility for the damages of yesterday? The presence of the past continues to be felt at least until justice can be done, in whatever form that may be. Exploring dimensions of historical responsibility structures debates about what such justice should look like.

But histories of violence are monstrous things in more than one respect. They swiftly become entangled and enwrapped with themselves. We can’t talk about who is to blame for genocidal acts, for example, without talking about the structural ruptures that lie behind them, that are entangled in them. Local crimes are suspended in global injustices. One history of violence leads to another.

It is also what Pan-Africanists must do today, building a future from the compounding damages and unsolved problems left both by colonial rule and the flawed nationalist projects that followed. As we follow such entanglements, a key question that emerges is how. The damage stays with us; asking how it came to be gives us clues as to what must be done with it. Understanding the violence of colonial rule, for example – whether conquest, control, dispossession or the inscription of new forms of structural discrimination – is an essential task for meeting postcolonial challenges. There is no return to what has been lost, but looking back may help reveal the paths towards building something new from what remains. This is what African nationalists attempted at independence, building new societies with the broken pieces of colonial territories. It is also what Pan-Africanists must do today, building a future from the compounding damages and unsolved problems left both by colonial rule and the flawed nationalist projects that followed.

But there is also another face to histories of violence, one that does more than show us what went wrong and why. Here history does not seek an explanation of how, or the framing of justice, but the witnessing of life. Emerging from the worst of human experience, some of those who do not move on also find means to live with. This must mean living with the loss and the damage, but also living with others – others who have lost, others who have harmed, others who have gained from that harm, others who will never understand.

In Rwanda and Burundi, two countries most beset by intimate violence over the past sixty years, the word is kubana: not to pursue justice, not to reconcile, but to live with another – ideally kubana neza, to live with another well. More modest a goal than achieving true justice or changing the nature of power, to live with another well buys a little time – time from which possible futures can emerge. As both countries have lamentably known, living-with is not in itself sufficient to prevent recurrence and escalation of violence over time; justice and transformation cannot be set aside. But in witnessing the practices of kubana neza we begin to find the truest value of violent histories for more hopeful futures: evidence that these futures have already been imagined – and, in part, lived.

Humility and utopianism together shape these possibilities. More hopeful futures are born from a confluence of historical paradoxes: a desire to ‘move on’ and a recognition that the past is always present; a desire to see a completely different world, and a modesty to act on the humblest of scales. The transformative power of forgiveness was the dream of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and this promise brought equal parts admiration and criticism. It asked the impossible, and attempted to build a collective future out of individual lives and gestures; it diluted or sacrificed justice – of many forms – for the sake of “moving on” towards its dream of the future, and left many behind in the process. But to the extent that such grand schemes have disappointed, they have also sketched something of the possible – a possibility that others, far from the spotlight, have lived.

Felwine Sarr argues for utopian ways of thinking as a means of liberating Africa from models and futures imposed from elsewhere. Daily acts of living-with give modest life to such utopias. Kubana neza is not a new idea. It is not in itself the product of violence. It can scarcely be boiled down to a simple set of policies to be implemented, nor does it displace the desire for justice. But it is the most valuable face of Africa’s histories of violence for the building of its futures. Looking at past violence – understanding how it is never truly past -– shows that living-with is possible, for some. And from that possibility, futures are made.

Electronic reference

Russell, Aidan. “Africa: Violent Pasts and Other Futures.” Global Challenges, no. 15, May 2024. URL: https://globalchallenges.ch/issue/15/africa-violent-pasts-and-other-futures. DOI: https://doi.org/10.71609/iheid-x4pv-6a94.BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

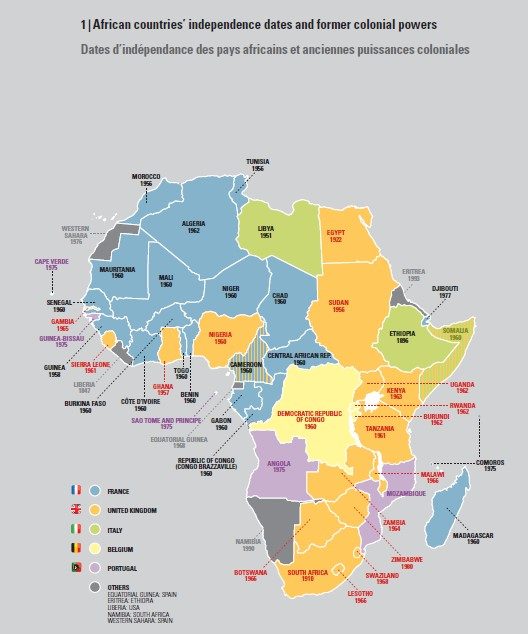

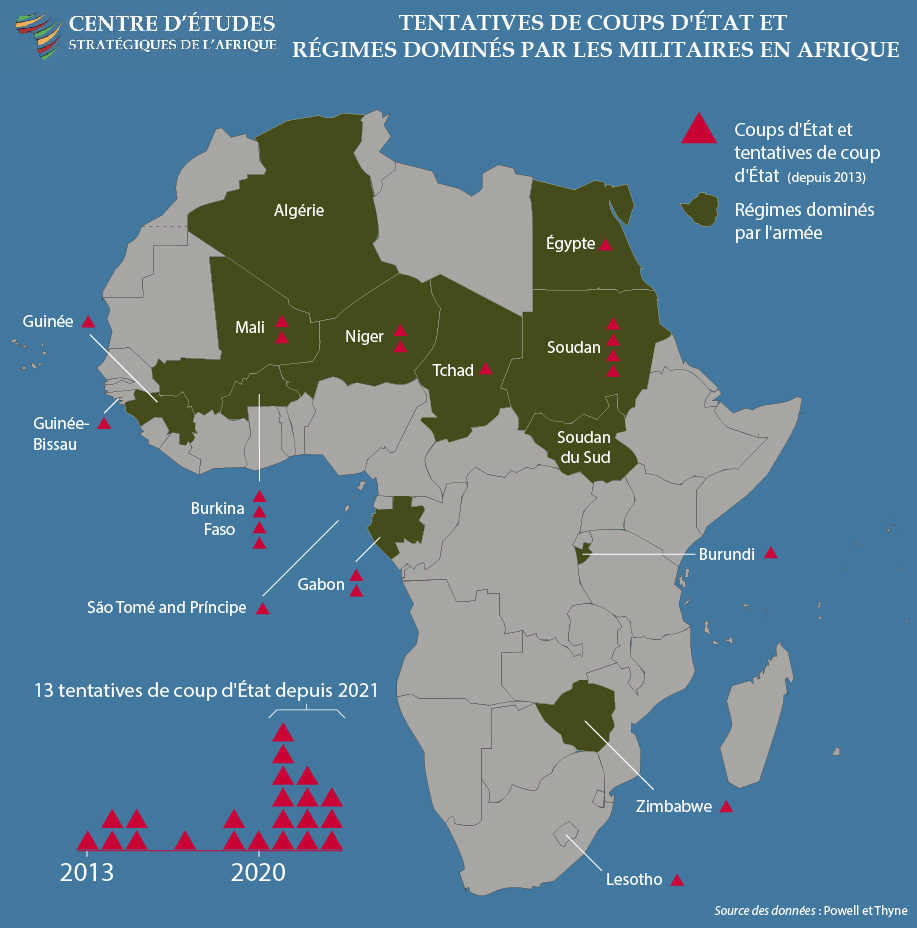

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

VIDEO | The Challenges of Demographic Trends in Africa, with Dêlidji Eric Degila

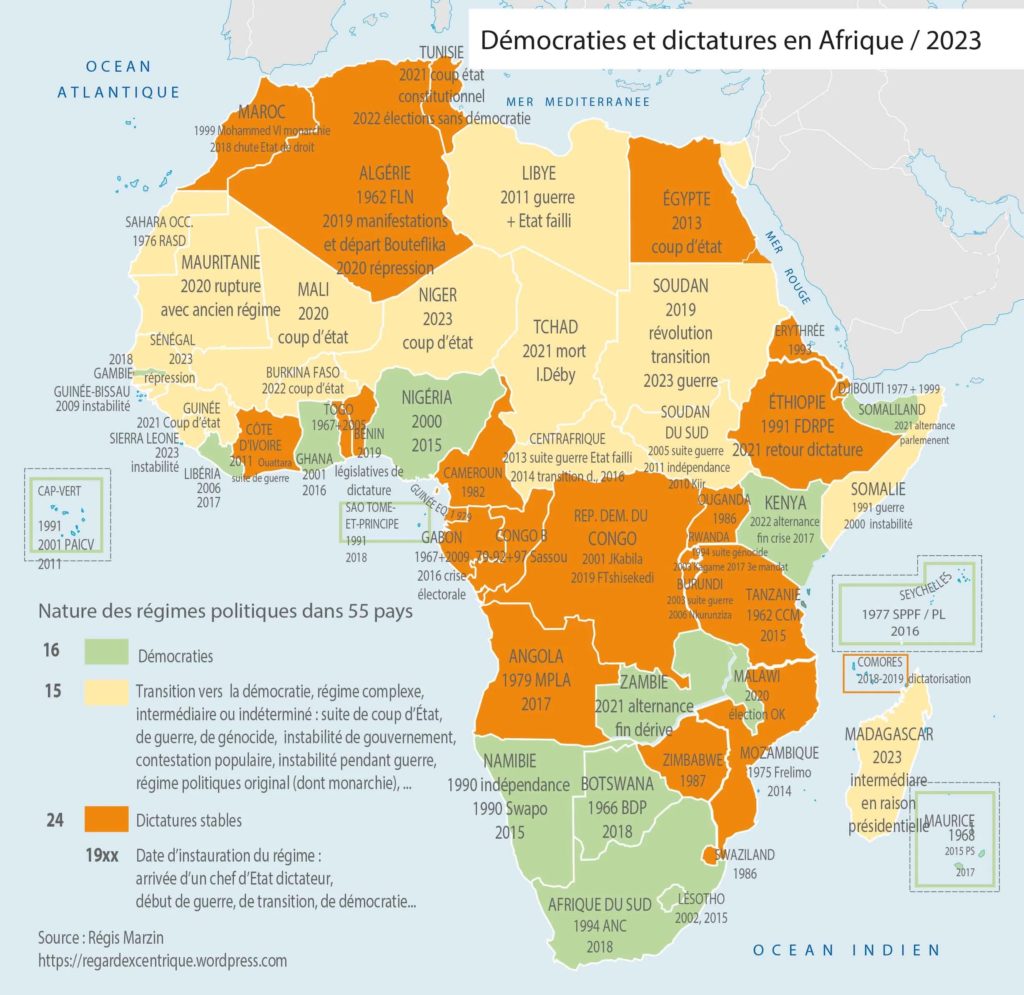

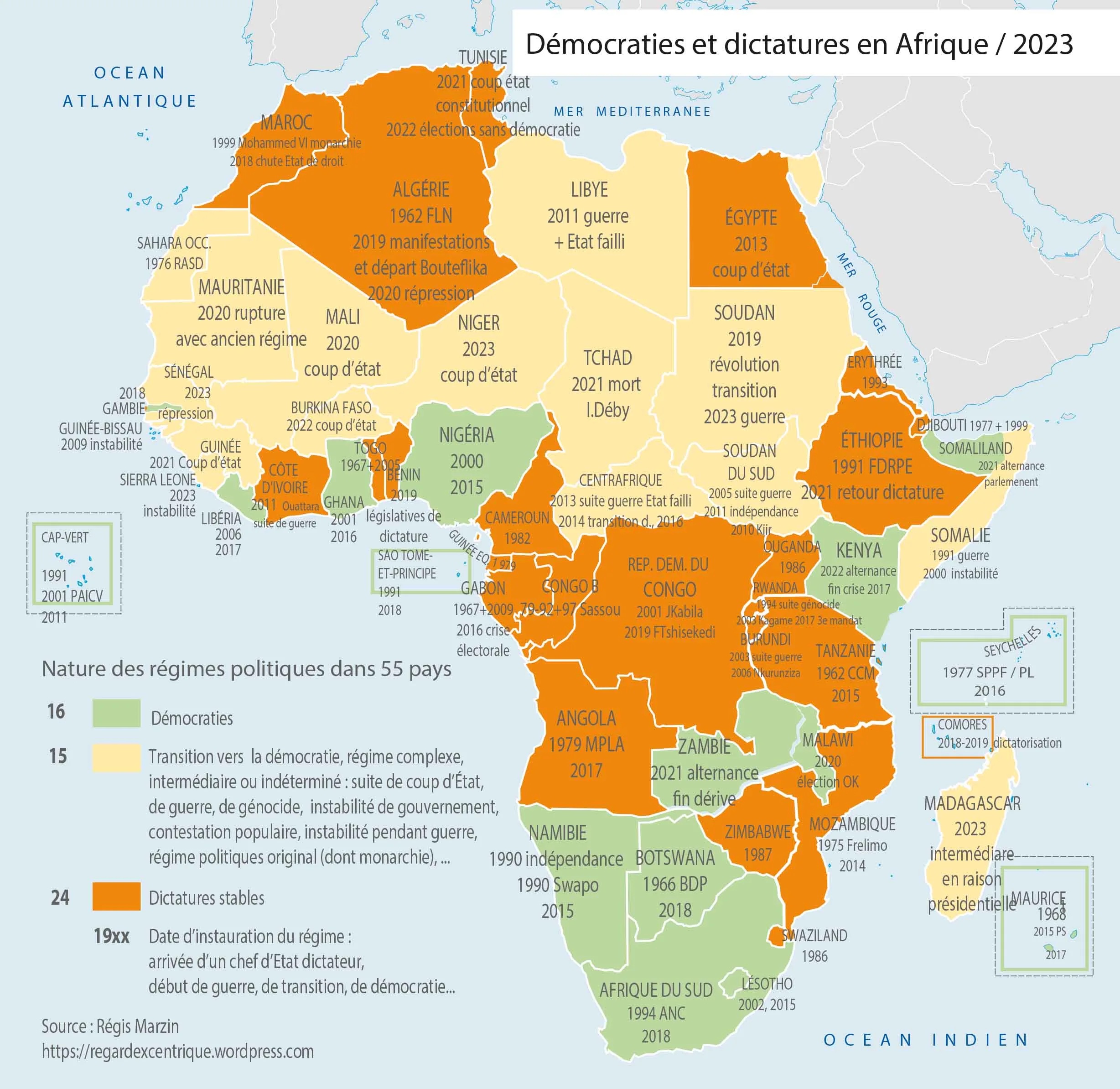

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

PODCAST | Ken Opalo on the Prospects of Democracy in Africa

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.

VIDEO | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa, by Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou

Geneva Graduate Institute

VIDEO | Africa in a 2030 Perspective, with Lord Mark Malloch-Brown, former Deputy Secretary-General of the UNDP

Geneva Graduate Institute

DOCUMENTARY | Missing Dollars: How Illicit Financial Flows Affect Developing Countries

Geneva Graduate Institute