Africas Rising: The 21st Century Promise?

Picking up on the ideas expressed by the oracles of the World Economic Forum, World Bank and OECD, António Guterres announced at the 2023 African Union Summit that “the 21st century has everything to be the century of Africa”. This idea marks a break in well-established narratives on the conflict between Western domination and China in the so-called “Asian century”. Could it be then that the coming decades will see a further reshuffling of the cards, with African countries establishing themselves as new powerful players on the international scene, boosted by sustained economic and demographic growth as well as new political leadership?

In 1998, Time magazine was one of the first to highlight the signs of African societies’ resurgence. Its title, “Africa Rising”, with the subtitle “A new spirit of self-reliance is taking root among many Africans as they seize control of their destiny”, quickly established itself as a concept for describing a period (2000–2015) of strong economic growth. At the end of 2011, The Economist caused a sensation by using the same title, with a focus on the commodities boom of the early 2000s. Accordingly, the notion of “Africa Rising” refers to a period of rapid economic growth across sub-Saharan Africa that started in the early 2000s and continues to today. The Financial Times defines “Africa Rising” as a “narrative that improved governance means the continent is almost predestined to enjoy a long period of mid-to-high single-digit economic growth, rising incomes and an emerging middle class”. It has thence become the epitome for associating African economies with economic prosperity, start-ups and growing financial investments.

Nevertheless, critics have questioned the notion of “Africa Rising” as a “stereotype”, Patrick Bond describing the notion as a neoliberal “chimera” spurred by international financial institutions (IFIs), which have not always abandoned their old mindset in which the future of African economies still essentially depends on the labour and resource attractiveness of the continent for foreign investors. Such an underlying vision no longer fits with the aspirations of African peoples themselves, as the latter do not wish to remain confined to managing internal affairs on their continent, especially if this means adopting new rounds of governance reform required by IFIs to attract foreign investors in order to service world markets with their natural resources. African states are now asserting their moral and political leadership in global affairs As Tim Cocks recently commented on the decision of the Pretoria government to take Israel to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) under the Genocide Convention, African states are now asserting their moral and political leadership in global affairs, and are ready to use all the international legal and political opportunities at their disposal to do so.

The term “Africa Rising” must then be used with caution. To capture a multifaceted reality, we propose to discuss the notion of “Africas Rising”: using the plural takes into account the fact that Africa is plural and complex (see Dêlidji Eric Degila’s article in this dossier), and that the visions of the world order within which different African states project themselves are also multiple and sometimes conflicting. Just like there are multiple Europes, there are many different possible Africas in a highly diverse continent: culturally, with over 3,000 ethnicities and more than 2,000 languages spoken, but also geographically and ecologically, economically, politically and religiously. Understanding this complex reality, analysing it as a whole, is a challenge, given the enormous disparities between the countries that comprise it, and the entangled transnational and international relations in which its past, present and future are embedded.

Why The Future Shall Be African

Exceptional Demographics

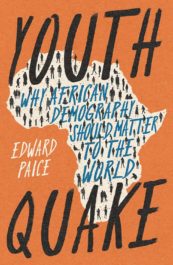

According to UN forecasts, around 566 million children will be born on the African continent in the 2030s. In the 2040s, the number of births is expected to overtake those in Asia, and the African working-age population will not only become the largest in the world but also the only one that is still growing. While some analysts see in this exponential demographic growth a unique opportunity for economic development, others, thinking in old-fashioned developmentalist terms, consider it as a “time bomb”, notably in the face of soaring youth unemployment.

The Key Role of Trade

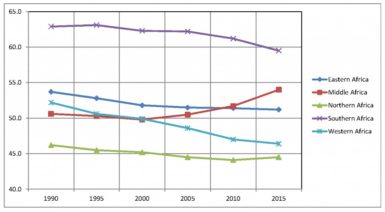

By 2024, Africa economies will comprise 11 of the 20 fastest-growing economies in the world. This success confirms the trend of sustained growth over the last 20 years. It is partly due to the transformation of trade policy on the African continent, with multilateral and regional trade agreements leading to increased liberalisation and trade flows. In 1998, Africa’s share of world merchandise trade was 1.9%, rising to 3.48% in 2008 before falling back to 2.49% in 2020.

Behind this favourable macroeconomic picture, however, lie major upheavals reflecting global geopolitical shifts. In 2009, China overtook the United States as Africa’s leading trading partner. In 2017, Sino-African trade stood at USD 170 billion, down from its peak in 2014, but still at levels 20 times higher than at the start of the millennium. Over the same period, trade between the United States and sub-Saharan African economies amounted to just USD 39 billion. Between 2006 and 2016, African imports from Russia and Turkey increased in value by 142% and 192% respectively. While African countries remain mainly suppliers of raw materials in the global trade order, when engaging in new trade partnerships they are stepping up initiatives to widen their manufacturing base and reconcile their need for investments with the preservation of national sovereignty.

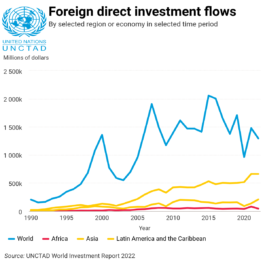

A Spike in Foreign Investment since 2000

African countries have witnessed a sharp rise in foreign investment over the last 20 years, reaching a record USD 83 billion in 2021 (compared with USD 2.8 billion in 1990). Economists, such as Vijay Mahajan in his 2008 book Africa Rising: How 900 Million African Consumers Offer More Than You Think, have waxed lyrical over the continent’s economic miracle. Charles Robertson’s The Fastest Billion: The Story Behind Africa’s Economic Revolution from 2012 likewise ensconces African economies’ fast-paced transformation. Written with a group of African economists and financial analysts from a leading emerging markets investment bank (Renaissance Capital), its aim is above all to counter the “Asian century” narrative. Africa’s GDP could indeed equal that of the European Union by 2050.

But while the economic data may suggest that African economies’ time has come, there are two problems with this vision of lasting growth coupled with high returns on investment. Firstly, foreign investment has fallen sharply and worryingly in the last few years.

Between 2020 and 2023, as China faced its own economic issues, it lent the continent just USD 1–2 billion, compared with USD 170 billion between 2000 and 2020. Secondly, even at its previous level, foreign investment in Africa remains insufficient. African economies need an estimated USD 2,800 billion between 2020 and 2030 to adapt to global warming and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Yet only USD 300 billion have been committed thus far. To close the gap, at least USD 250 billion would be needed annually, or around 10% of Africa’s total GDP.

A New Diplomatic Scramble for Africa?

African countries are now also playing a growing role on the world stage, increasingly demonstrating their desire for a new, more equitable international system. After centuries of colonial domination by European powers, and the failure to establish the New International Economic Order (NIEO), which aimed, among other goals, at abolishing the colonial-inherited sovereign debts that plagued the budgets of newly independent African states, governments and companies around the world are rushing to strengthen their diplomatic, strategic and commercial ties with African states. Their goal may not be altruistic, as commodity traders see record profits from the volatility of commodity prices. But the new scramble for African ties gives African states a stronger voice on the world stage. A good indicator of this growing interest in African states, and correlated growing agency gained by African states in global affairs, is the number of diplomatic missions opening on the continent: the scale of foreign diplomatic engagement is unprecedented, with more than 320 embassies opening across the African continent between 2010 and 2016. Turkey alone has increased the number of its embassies from 12 in 2002 to 44 as of 2022. In 2018, India announced that it would be opening 18 embassies.

The “Return” of African Intellectuals

While the African diaspora has long been primarily an economic force (according to the World Bank, USD 53 billion in remittances were transferred to sub-Saharan Africa in 2022), a new trend is emerging among expatriate African elites: returning home. Whether this return is driven by a sense of opportunity, a feeling of connection, or the desire to contribute to their country’s development, it bears witness to the strength of hope in its future. In September 2018 in Washington, Nana Akufo-Addo, the President of Ghana, officially launched the “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” for the African diaspora, to give new impetus to the quest for unity among Africans on the continent.

The economist Felwine Sarr is symptomatic of this trend with his decision to return to Senegal. Through initiatives such as the literary project Écrire l’Afrique-Monde, Felwine Sarr and Achille Mbembe challenge conventional discourses and promote a more inclusive and dynamic future for the continent, likening the world to a “pluriverse”. In their view, “Europe is no longer the centre of the world, even if it remains a relatively decisive player. Africa, for its part, and the South in general, are increasingly depicted as privileged theatres where the future of the planet is likely to be played out.”

Beyond the question of a physical “return”, and whether the latter needs to be temporary or permanent to bear fruit, new analytical tools are being developed by African intellectuals, artists, urbanists and architects to better decipher the present and act as a catalyst of change in the era of the Anthropocene. African thinkers have focused on climate change, decoloniality, new social utopias and the global nature of African issues, devising new forms of political, economic and social production, and new ways of articulating the universal and the singular. As a laboratory of new ideas, the imaginary constitution of new Africas have come to play a pivotal role on the world stage. In the words of Achille Mbembe: “In fact, the renewal of our cultural, political and linguistic imagination, and of our thinking about the human being in general, all this now passes through this mirror of the world that Africa has become.” In architecture, for instance, Mariam Issoufou has questioned the use of concrete in urban dwellings, promoting the use of less impactful materials like raw earth. Her work explores the paradoxes of such projected Africas: the production of concrete may be an environmental heresy, but it remains the source of some of the largest fortunes on the African continent and is still supported by IFIs who see in it a source of income for the African middle classes.

Adopting a Different Relationship with Nature

Not only intellectuals but also African civil society organisations are working to propose a development paradigm for the African continent that emphasises sustainable resource management, conservation and respect for its rich biodiversity.

An emphasis on more sustainable agro-ecological practices, as advocated, for example, by Calestous Juma, could significantly contribute to solving African countries’ food security problems. But these ambitions face important hurdles. The risks of resource and soil degradation, natural disasters, desertification, deforestation, reduced biodiversity, increased urban pollution and increased drought remain considerable, as do their consequences in terms of conflicts and uncontrolled migration. The expected growth in population and urbanisation will place an additional strain on sustainable development in some African countries. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of eco-exiles or eco-refugees – 15 million worldwide in 2005 – is set to increase three or fivefold.

The very matrix of conservation policies in certain African countries, which has been the playground of conservation movements since colonial times (as Bill Adams’ article in this dossier illustrates), also deserves to be questioned. Guillaume Blanc shows that in the twentieth-century, more than a million people were expelled to make way for animals, forests or savannahs during the set-up of a network of some 350 national parks. This perspective invites us to question not the choices made by the local peasantry, but the Western model of life and its emphasis on global tourism, as well as the power of transnational coalitions of conservationists in the world to impact local populations.

Questioning Development Aid Paradigms in Africas

In parallel to this reconceptualisation of the role of nature in development, many African thinkers have radically questioned the effectiveness of development aid and its impact on long-term progress and self-sufficiency. Dambisa Moyo asks in Dead Aid why the USD 1 trillion in development assistance over the last fifty years has not enabled Africans to improve their situation. The Zambian economist proposes that development aid, which accounts for almost 15% of Africa’s GDP, should be phased out. For her, as for many other economists today, the harmful effects of aid are numerous: aid distorts competition, corrupts the ruling classes, creates a bloated administration and exacerbates ethnic tensions over the sharing of the “spoils”. According to Rosa Whitaker, who set up The Whitaker Group in 2003 to mobilise multinational investment in African economies without “resorting to official aid”, it is clear that today “we need to replace paternalism with partnership”, which means co-constructing the solutions to alleviate poverty, sustain economic growth and protect environmental resources between local societies, national governments, and transnational groups of experts.

African (human and non-human) resources were exploited and depleted against the interests of the continent’s populations during the first three industrial revolutions. It is therefore crucial for African peoples to defend their interests during the fourth – upholding both the continent’s human and non-human potential. In Africa’s Fourth Industrial Revolution, Landry Signé imagines Africas capitalising on a rapidly evolving technological landscape, perhaps offering the opportunity to “leapfrog” certain stages of the investment- and industry-heavy European and Asian development models of the 19th and 20th centuries, eschewing their harmful environmental impact.

This idea is echoed by Dayo Olopade in The Bright Continent: Breaking Rules and Making Change in Modern Africa, which paints a nuanced portrait of African diverse societies and cultures, challenging stereotypes and highlighting the ingenuity and resilience of African communities in the era of climate change. According to such narratives, artificial intelligence, digital technologies and green industrialisation will gear Africa’s economic future to more environment-friendly services and initiatives, making African countries less dependent on IFI-led mega-infrastructure projects that they have struggled to implement in the past.

Persistent Stumbling Blocks

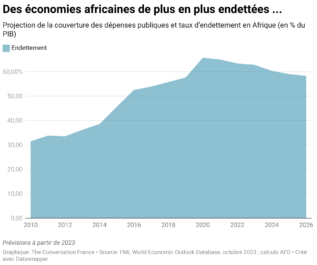

The optimistic and at times “Afro-euphoric” vision of a radiant future for the African continent must not blind us to the major challenges and limitations that need to be overcome if the continent’s full potential is to be realised: widespread poverty, inadequate infrastructure, political instability and deficiencies in governance, a heavy dependence on the extraction of natural resources, and high youth unemployment rates. In the face of these interconnected issues, as well as others such as soaring public debt, adverse climate change effects, bottlenecks in foreign investment, food insecurity, unmet health needs, widespread gender-based violence and lingering conflicts (as discussed by Aidan Russel’s article in this dossier), some analysts refer to an African “polycrisis”. Added to this are systemic problems such as corruption, weak institutions and limited access to education and healthcare, which also plague European, or South and North American politics, although differently and each time with specific historical idiosyncrasies. Even though it is premature to declare the end of “Africas Rising”, the challenges faced by the continent in the years ahead remain daunting.

Persistent Poverty

Although relative poverty is falling in most African countries, absolute poverty levels are still on the rise, with population growth rates offsetting falling poverty rates.

One explanation commonly put forward for this situation is the lack of investment in the fight against poverty. It is argued that USD 1,000 billion would be needed across Africa to eradicate poverty by 2030. To achieve this aim, sub-Saharan African societies would need to replicate China’s record of poverty reduction over the last three to four decades. Yet most African economies are struggling with low GDP and rising debt levels.

Economic Inequality

Despite significant improvements in life expectancy, per capita income and access to education, inequalities remain excessively high on the continent. With an average Gini index of 41.5, sub-Saharan Africa, taken as a whole, remains, according to the World Bank, the second most unequal region in the world after Latin American and the Caribbean. The much-debated emergence of an African middle class contrasts with the reality of a distribution of the benefits of economic growth that is often concentrated among the elite, leading to widening disparities between rich and poor. This growing gap is exacerbating social tensions, fuelling discontent, and undermining social cohesion. The fight against economic inequalities requires global policies aimed at redistributing wealth, and an important element of this fight is to control the illicit capital flows referred to by Gilles Carbonnier in his article in this dossier.

An Anarchic Exploitation of Resources

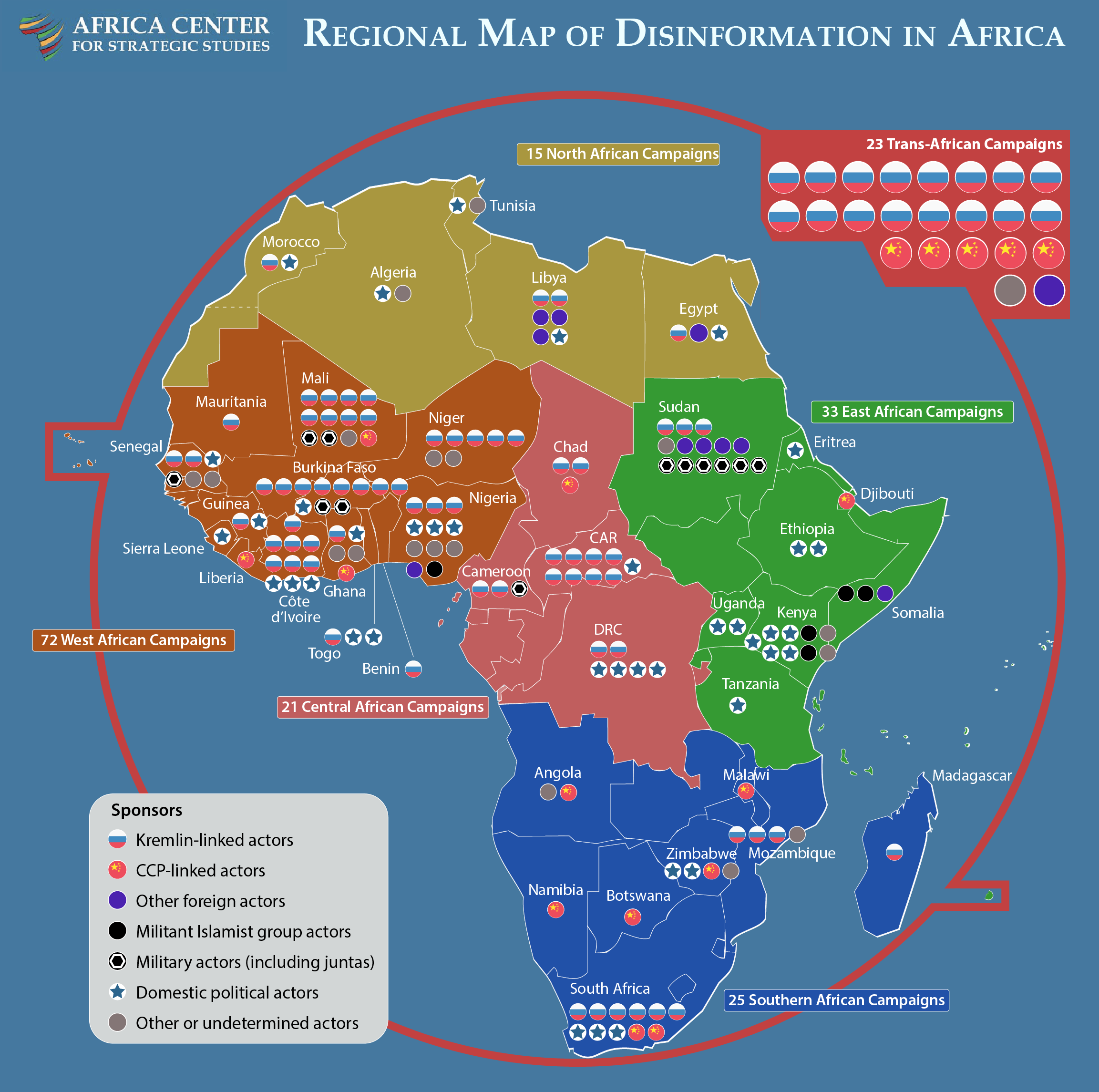

African lands are endowed with abundant natural resources, from minerals to oil, timber and agricultural land. On a global scale, it is estimated that the continent accounts for 40% of gold reserves, 30% of mineral reserves and 12% of oil reserves. However, the exploitation of these resources generally brings few benefits for local communities or African citizens. There are two main reasons for this situation, often described by economists as the “curse of raw materials in Africa”. Firstly, the volatility of commodity prices adversely impacts the GDP of exporting countries, leaving commodity traders – most often located in Europe, in Switzerland in particular – to make the largest profits. Moreover, these natural resources and the financial windfalls they generate give rise to major problems of governance and corruption, involving local governments as well as multinationals and foreign powers, not only from Europe, the United States, and “the West” in general, but also Russia or China. In this context, the role of the Russian-based Wagner Group should not be forgotten in spurring violence against African political opposition leaders, as this group is not just a security contractor but has become a key stakeholder in the resource extraction business of the African mines.

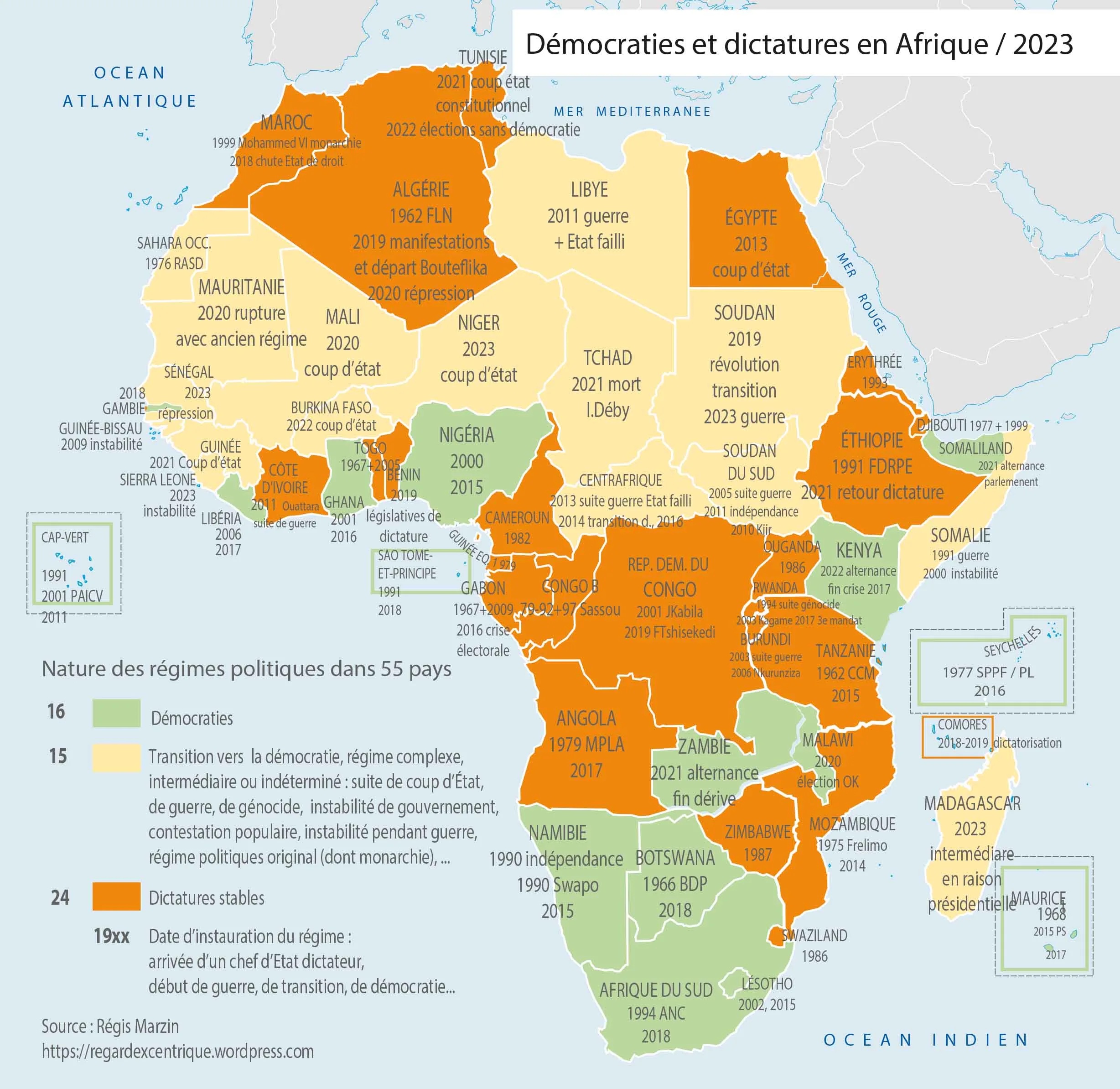

Governance Challenges

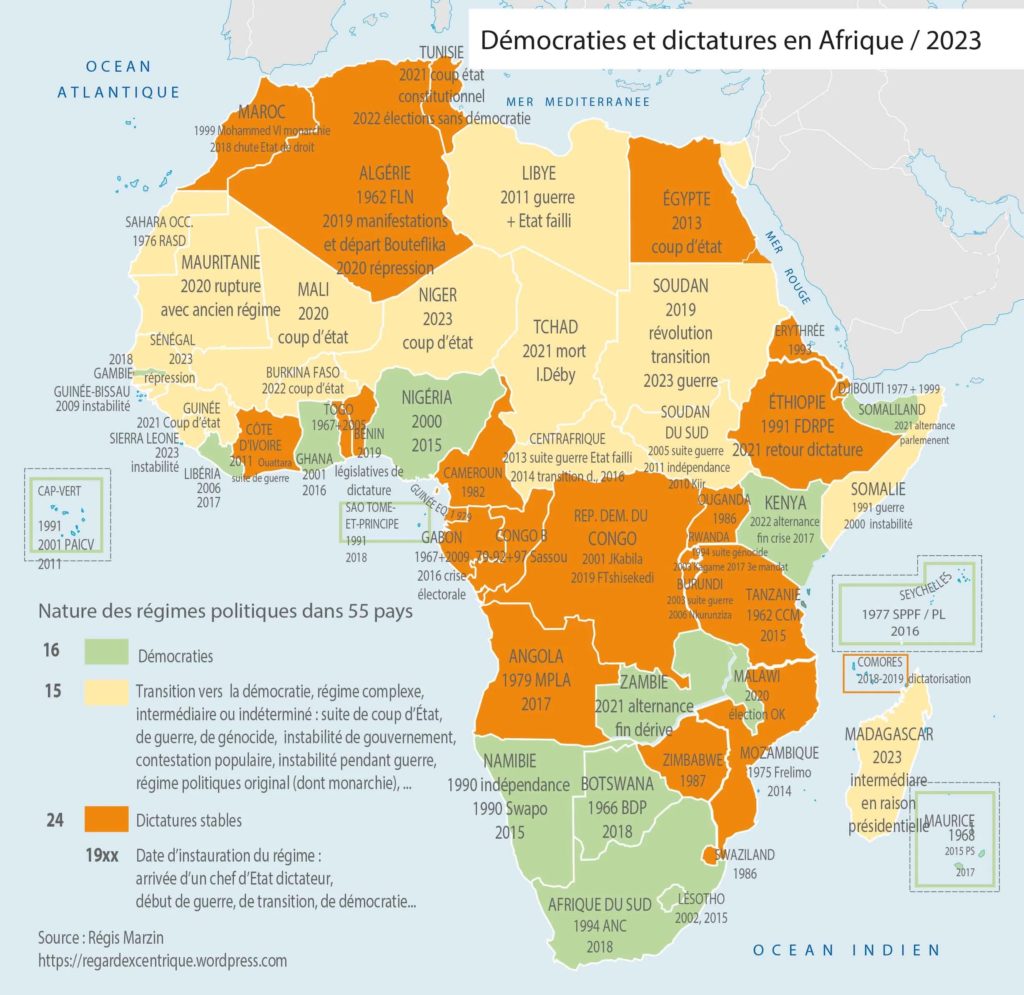

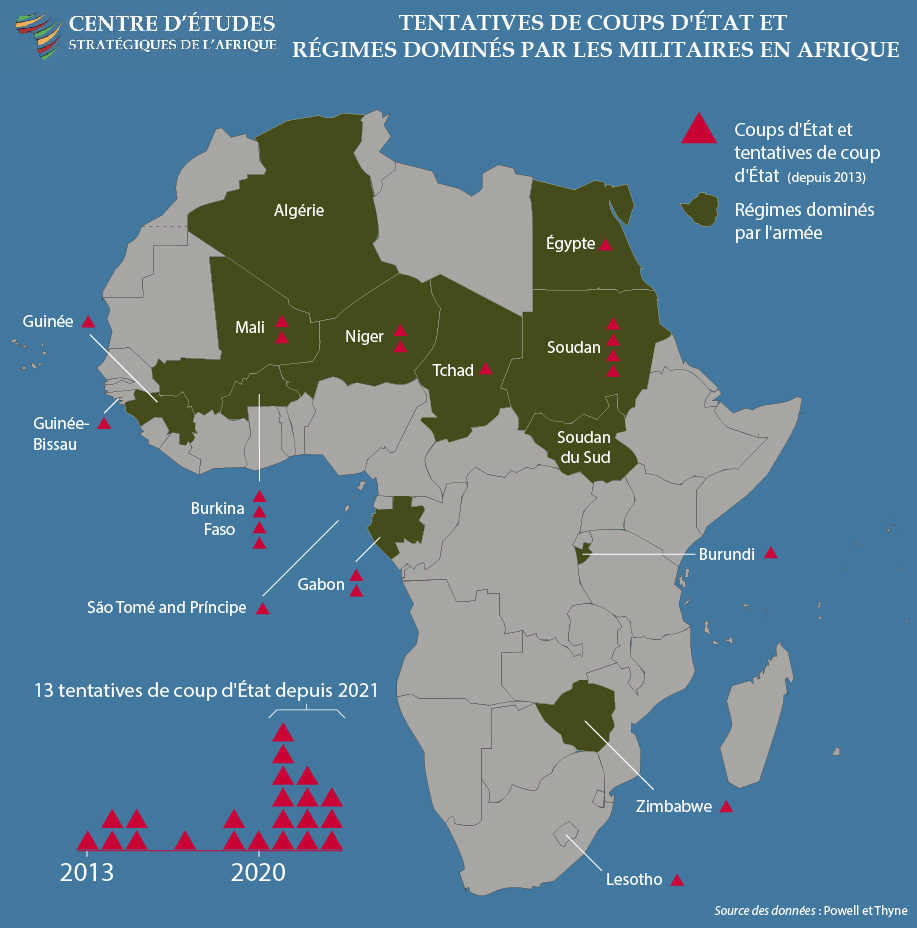

Against a backdrop of fragile or declining democracy (see Franck Afari’s article in this dossier), political instability, ethnic tensions, religious developments (see Anna-Riikka Kauppinen’s article in this dossier) and opaque government practices, African economies are at risk of losing the benefits of two decades of economic growth. In particular, the circumvention of term limits by political leaders is at the heart of many governance dysfunctions across the continent. It is also linked to higher levels of autocracy, corruption and conflict and a tendency towards coups d’état. Despite democratic progress in certain African countries (e.g. Senegal, Ghana, Zambia) and a new generation of women who have taken up leadership position in African politics (see Norita Mdege’s article in this dossier), in recent years leaders that have unconstitutionally stayed in power have shaped Africa’s political landscape: today, 14 African leaders have been in power for more than two terms. This autocratic drift is happening in an increasingly violent global context, with wars in Europe and the Middle East destabilising and reorganising alliances between state actors and non-state actors. For Thierry Vircoulon, diversifying partnerships is a logical adaptation to this multipolar world in the making, even if the breakaway strategy of African partners is justified by a quest for sovereignty that is not always associated with the expression of the will of the people.

Conflict and Increased Military Engagement

While no African state yet has a permanent seat (and associated veto) on the UN Security Council, three states currently have non-permanent representation (Algeria, Sierra Leone and Mozambique); all the while, the African continent has witnessed a fierce competition of foreign military forces for the last two decades. The fight against terrorism and the defence of commercial and economic interests have been the main drivers for emergency interventions and, more structurally, for the establishment of new military bases. Political developments in certain countries (Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso) have contributed to the reorganisation of military partnerships. The French presence in particular has diminished, leaving the field open to Russia, which since 2014 has signed 19 military agreements with African states. Although the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM) plays a relatively discreet role, the US continues to invest in its bases in Africa. Is this because China, which is now the largest arms dealer in sub-Saharan Africa and has defence technology links with 45 countries, is planning to open a second military base in West Africa (after the one in Djibouti)? Undoubtedly. The oil-rich Arab states are also building bases in the Horn of Africa. Between hidden Russian military influence, destabilisation and electoral interference, and the affirmation of Chinese interests in securing access to natural resources and supporting friendly governments, the African continent is the object of much covetousness, with Europe – and America – losing their historical advantage.

The Limits of Neo-Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism, a powerful ideology promoted by many leading African and Afro-American leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois, who encouraged solidarity between Africans and people of African descent in view of achieving total independence of the African continent, has been a structuring force in the long twentieth century. In 2015, the African Union produced Agenda 2063, entitled The Africa We Want, a blueprint for imagining Africa and transforming it into a global power of the future. However, its application at a continental level has been much criticised and there is no shortage of alternative ideological models for a diversity of Africas. The aim is to make Africas at the start of the third millennium a subject (actor) and not an object (spectator and victim) of globalisation These include modernised versions of “Neo-Pan-Africanism”, a strategy that is part of “open Afrocentrism”, aiming to reconcile African and imported values and taking inspiration from domestic knowledge and practices as well as foreign experiences. Here, too, the aim is to make Africas at the start of the third millennium a subject (actor) and not an object (spectator and victim) of globalisation. But, then, these alternative models, widely discussed in African universities today, have yet to materialise in practice.

Conclusion

The economic times in which the African societies find themselves are undeniably unique. In a more complex and multipolar world, African states and peoples have an important role to play. The quality of the education offered to their young populations, their respect for difference, their success in confronting complex eco-political challenges and the continued advancement of the continent’s economic and political integration will certainly be determining factors in their success. Still, as sketched in this quick panorama, Afro-optimists will continue to oppose Afro-pessimists. For some, the current economic growth contains the seeds of a “second independence” that could finally deliver on the promises of the NIEO. Others see it as a return to new dependencies: they fear that contemporary African sovereignty, instead of becoming autonomous, can replace dependence with multi-dependence. The debate will continue for some time, as the authors convened for this special issue illustrate.

-

1

In from the Periphery: How Africa Can Contribute to the Making of a Pluriversal World

In from the Periphery: How Africa Can Contribute to the Making of a Pluriversal WorldAfrica has often tended to be marginalized both in world politics and in the academic study of international relations. Challenging the traditional view of African nations as primarily local actors, Dêlidji Eric Degila makes the case for a uniquely African contribution towards the creation of a more inclusive, pluriversal world.

-

2

Energy Transition and Global Tax Reform: Boosting Africa(s) on the Rise?

Energy Transition and Global Tax Reform: Boosting Africa(s) on the Rise?Growing demand for the commodities required to drive the green transition has the potential to bring considerable wealth to a number of African nations. However, argues Gilles Carbonnier, if this boom is to bring lasting benefits, major investments in education and infrastructure will also be required, alongside fiscal measures implemented at a global level.

-

3

Africa: Violent Pasts and Other Futures

Africa: Violent Pasts and Other FuturesThere is no shortage of histories of violence in Africa. What can they offer us for the future, beyond reminding us of the worst events of the past? For Aidan Russell, beyond pursuing justice and explaining what went wrong and why, history must also witness life itself: how some of those who do not “move on” also find means to live well with others (kubana neza).

-

4

“An Epidemic of Coups d’État” in Africa

“An Epidemic of Coups d’État” in AfricaFrom Mali to Chad, from Guinea to Gabon, Africa has witnessed a resurgence of coup attempts in recent years. Reviewing the long history of the coup in Africa, Frank Afari examines the factors behind its continuing success across the continent and the tension between the coup as a tool of regime change and a widespread desire for democratic succession.

-

5

African Conservation Futures

African Conservation FuturesThe national park – despite its origins as a Euro-American construct from the colonial era – remains a cornerstone of conservation programmes across Africa. Probing the diversity of African experiences of conservation, Bill Adams explores the history of the national park in Africa, alongside other ongoing efforts to preserve the continent’s biodiversity for the future.

-

6

Who Is Rising? Popular Critiques of the Economic Power of Mega-Churches in Ghana

Who Is Rising? Popular Critiques of the Economic Power of Mega-Churches in GhanaRecent decades have seen substantial growth of Christian mega-churches in countries across sub-Saharan Africa. Analysing the rise of the mega-church in the Ghanaian context, Anna-Riikka Kauppinen examines how these churches have come to play a significant role in the economies of their host countries.

-

7

Towards Greater Visibility of African Women in Politics

Towards Greater Visibility of African Women in PoliticsHistorically, men have played a dominant role in setting the tone of political discourse in postcolonial Africa, not least because they have held most senior positions in politics and the media. In recent years, writes Norita Mdege, the political representation of African women has begun to increase, a trend that itself represents a contribution to the plurality of African democracy.

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

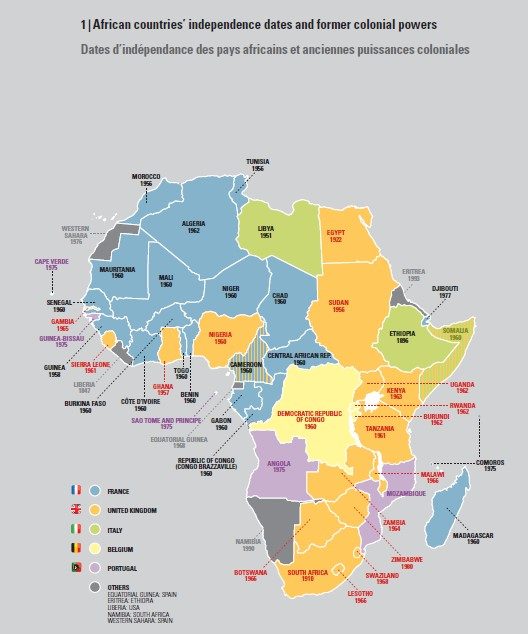

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.