Energy Transition and Global Tax Reform: Boosting Africa(s) on the Rise?

Countries in Africa are estimated to lose around USD 90 billion every year to illicit financial flows. Addressing this major outflow of wealth requires addressing both push factors in commodity-exporting states and pull factors in the world’s main financial and trading hubs, as part of the global tax governance reform.

“We don’t know the situation in your country. It’s you: you have to make regulations for your country. Not we in Switzerland.” This is what a Swiss parliamentarian replied to a Ghanaian filmmaker who was shooting a documentary film on illicit financial flows (IFFs) in commodity trading. Every state is indeed expected to enact legislation to protect and advance its own interests. But is this good enough? To what extent are stronger international cooperation and global governance necessary to help resource-rich African countries such as Ghana mobilise domestic resources for development? And, to start with, is Africa indeed on the rise?

Aggregating 54 very diverse states into one homogenous African entity does not allow for sweeping generalisations; in this article, we will focus on commodity-dependent countries. Besides, in the African context, macroeconomic data does not necessarily reflect reality, as most economic activities in Africa are informal and statistical offices under-resourced. That said, one thing is certain: Africa’s population is on the rise. It is estimated to have doubled since 1995 to reach 1,460 million in 2023, or 18% of the world’s population. Forecasts indicate that Africans may number 2,485 million by 2050, accounting for over one in every four humans. The continent will remain comparatively young, with a median age moving from 18 today to 25 by 2050.

Such a steady demographic growth raises challenges. For example, a high youth bulge tends to be associated with a higher risk of armed conflict, aggravated by ever greater climate risks. Additionally, the expansion of cities, accentuated by migratory pressures, requires massive investment in urban infrastructure. But demographic growth also offers unique opportunities: Africa’s comparative advantage is shifting from a relative abundance of land – which led many countries to specialise in raw commodity exports and extensive agriculture – to a relative abundance of labour. To stimulate job creation and sustainable development, experts and policymakers are looking at ways to “leapfrog development” toward a green economy, drawing on the digital and energy transitions while skipping polluting industrial stages.

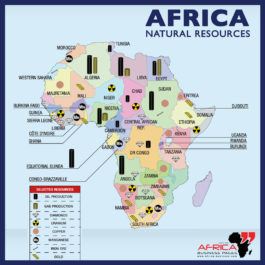

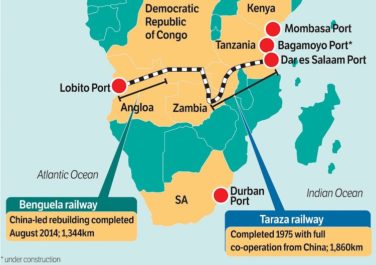

Africa is estimated to hold over a fifth of the world’s supply of the critical minerals needed for the energy transition, such as cobalt, copper, manganese and lithium. Countries with the largest reserves have long been courted by major powers vying for access to critical metals and minerals. The opening in 2023 of the Lobito railway corridor linking Congolese and Zambian mineral deposits to the Atlantic coast is seen as a major milestone, supplying American and European industry and reducing dependence on China. The United States and the European Union have backed this rail project and signed deals to develop extraction and processing capacities in Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

How can we prevent this commodity boom from turning into yet another resource curse for producer states? First, the governance of critical minerals requires effective checks and balances at domestic and global levels together with solid social and environmental safeguards. Second, economic diversification is key, all the more as industrial mining is capital-intensive but does not create many jobs (contrary to informal and small-scale mining). This calls for moving up the value chain, for example by building local refining capacity and producing battery parts for export, as well as e-motorcycles and other goods and services for booming domestic markets and the growing African middle classes. This, in turn, requires investing in education and infrastructure.

Funding needs are massive at a time when African countries face tight budgetary constraints and high debt levels. The African Development Bank estimates that the continent needs about USD 1,300 billion annually to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in addition to USD 2,700 billion to implement its climate commitments by 2030. Africa must thus mobilise huge resources while it is estimated to lose about USD 90 billion annually to IFFs. Tax evasion by mining firms has been estimated to deprive sub-Saharan Africa of up to USD 730 million a year. In a nutshell, African countries must be able to strengthen their tax base and raise their tax-to-GDP ratio that currently lies at 16% (compared with 33% in OECD countries).In the context of heightened North-South tensions and calls to do away with double standards and colonial legacies, the strengthening of a fair and transparent global tax system is a critical part of a broader agenda to restore trust in multilateralism.

Returning to the Swiss parliamentarian’s quote suggesting that African states such as Ghana must address these issues themselves: research suggests that this is only part of the solution. To curb IFFs, commodity-dependent African countries can indeed adopt a range of measures, and technological innovations can help. Yet, enduring pull factors must simultaneously be addressed in major financial and trading hubs. At the global level, tax governance reform must preserve the policy space for African countries to implement solutions adapted to institutional and contextual realities.

African leaders have thus called for a more inclusive process than that of the OECD tax reform framework. In November 2023, the UN General Assembly saw 125 states support a Nigeria-led proposal to place negotiations on a global tax convention under the auspices of the United Nations. This was hailed as a victory in a decades-long struggle by developing countries for fairer tax rules, allowing for more effective participation by the Global South than has been the case thus far under the aegis of the OECD. In the context of heightened North-South tensions and calls to do away with double standards and colonial legacies, the strengthening of a fair and transparent global tax system is a critical part of a broader agenda to restore trust in multilateralism.

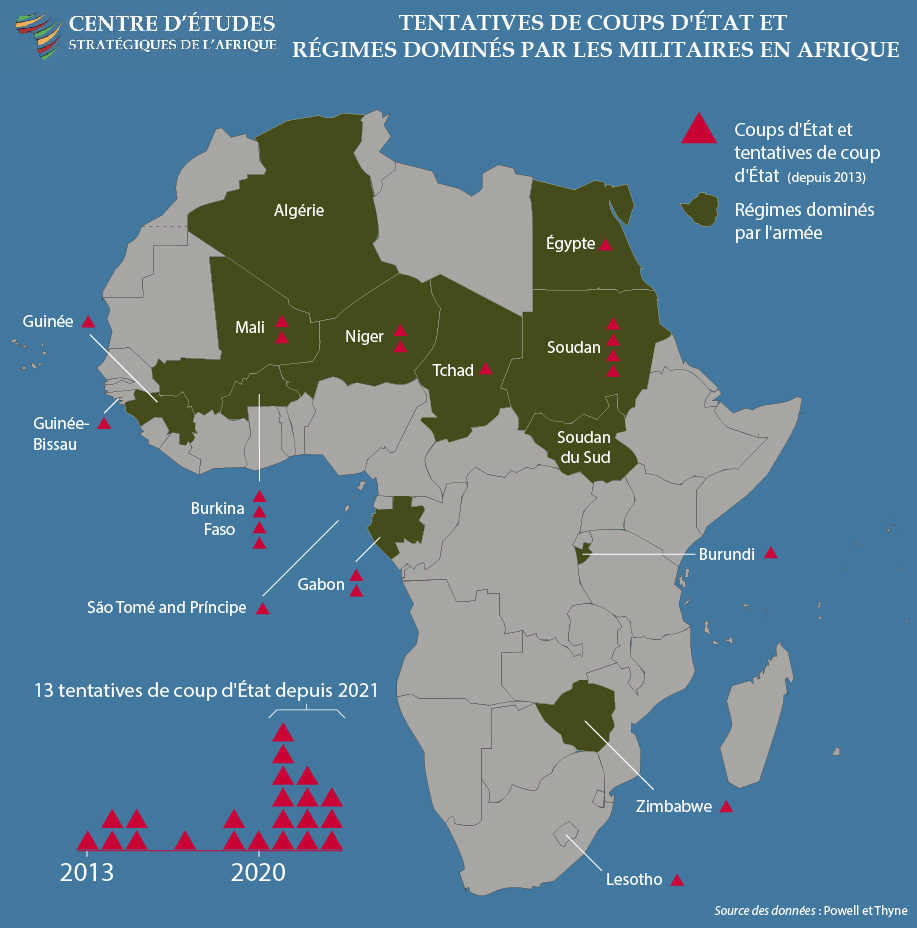

BOX | A Brief History of Coups in Africa

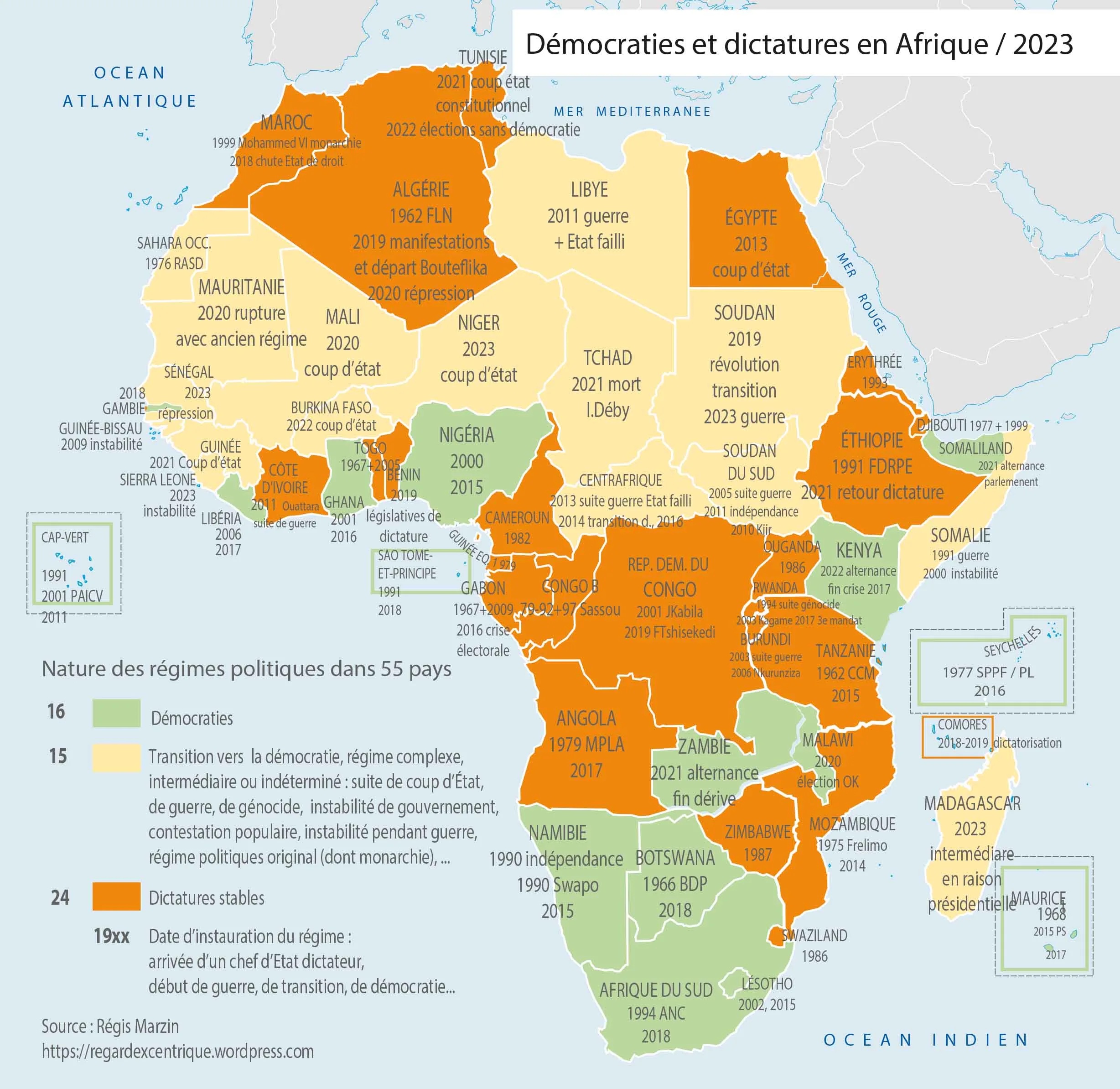

A coup d’état (literally a “strike against the state”) is an unconstitutional or enforced overthrow of a government through force of arms by the military or by armed rebel groups. There have been over 200 coups in Africa since the 1960s, with an average of 20 successful coups each decade between the 1960s and the 1990s. Indeed, by the 1980s, about 90% of African states had experienced a successful coup or an attempted putsch. Only a few countries, such as Botswana, Cape Verde, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Namibia or South Africa, have enjoyed unbroken democratic growth since independence.

The post-Cold War liberal turn reinstated a revival of interest in liberal democracy and an imposed dose of neoliberal structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). Many African countries – already plagued by what historian Paul Nugent has termed as a “fatigue” with the misrule of “men in uniform” – embraced liberal democracy for its promises of rule of law, good governance and constitutionalism. By the year 2000, almost every African country had held elections, and from the 2000s until recently, Africans enjoyed a relatively more stable experiment with democratisation despite sporadic episodes of violent reprisals.

BOX | A Brief History of Democracy in Africa

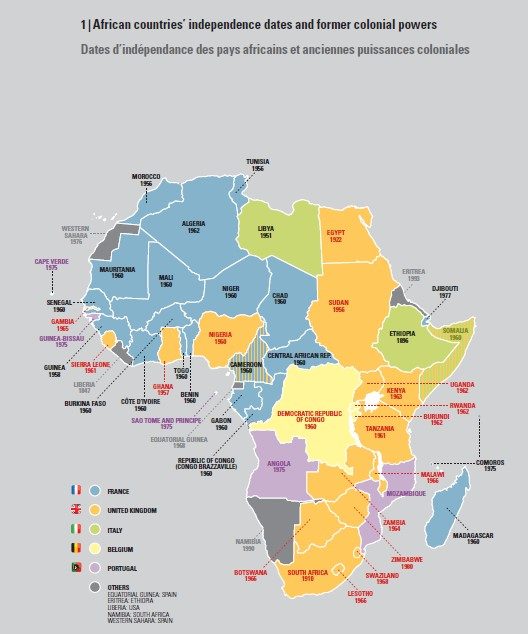

Africa’s first brush with liberal democracy came in the shape of what the late Africanist scholar and international relations expert Ian Taylor has described as “rudimentary facsimiles” of systems of government and legislatures, bequeathed by departing colonialists to the newly independent African countries.

In the early decades of Africa’s independence, most African leaders quickly imposed their iterations of democracy, using the force of unifying rhetoric to mobilise mass solidarity for statehood and nation-building. Some, like Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, Leopold Senghor, Julius K. Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, crusaded for an African-style democracy based on ideas about African unity, emphasising the “communitarian” character of African societies in contradistinction to the perceived “individualism” inherent in Western liberal thought. Some even modified or obliterated their inherited democratic institutions, frequently dismissing them as colonial burdens unsuited to African conditions. They touted their versions of African-style democracy as a bulwark against the supposedly harmful effects of multiparty democracy and frequently exploited them to legitimise oppressive regimes. The result was a string of one-party systems of government, authoritarian regimes, personalist rule and dictatorships, all of which throttled the seedlings of nascent democratisation and gave rise to internal disaffection among their citizens.

BOX | African Politics during the Cold War

Africa’s independence (and, indeed, the entire decolonisation movement) occurred at the height of the Cold War, as the two rival superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, clashed over the continent for control of its resources and its political allegiance.

The newly independent African nation-states had two key goals: establishing united and stable nation-states and encouraging economic growth and diversity to satisfy the high aspirations of their newly enfranchised populaces. Development was an ardent goal that included access to education, adequate healthcare, jobs, infrastructure, security and decent housing. Yet African leaders were also constrained in the political and economic choices that they had to make, being pressured to avow political allegiance to either the Eastern or the Western Bloc, the vanguards of communism and capitalism, respectively.

Faced with the pressure not to profess allegiance to either side so as to avoid antagonising the other, some leaders of these newly independent African countries – Nkrumah, Nyerere and Touré, for example – saw the overtures of the two blocs as a form of neocolonial reconquest and insisted on the right to have amicable relations with both in what they termed “positive neutrality”. Despite their ambivalence, many African countries drifted towards one or other side of the divide – a choice that came at a significant cost. The story of America’s withdrawal of financial support to Ghana as a punishment for the latter’s pro-socialist and pro-Eastern stance has been well-documented. Indeed, Ghana’s drift towards the Soviet bloc and China subsequently provoked the CIA’s complicity in overthrowing the Nkrumah administration by coup, attesting to the palpable threat and impact of Cold War politics on the stability of Africa’s early years.

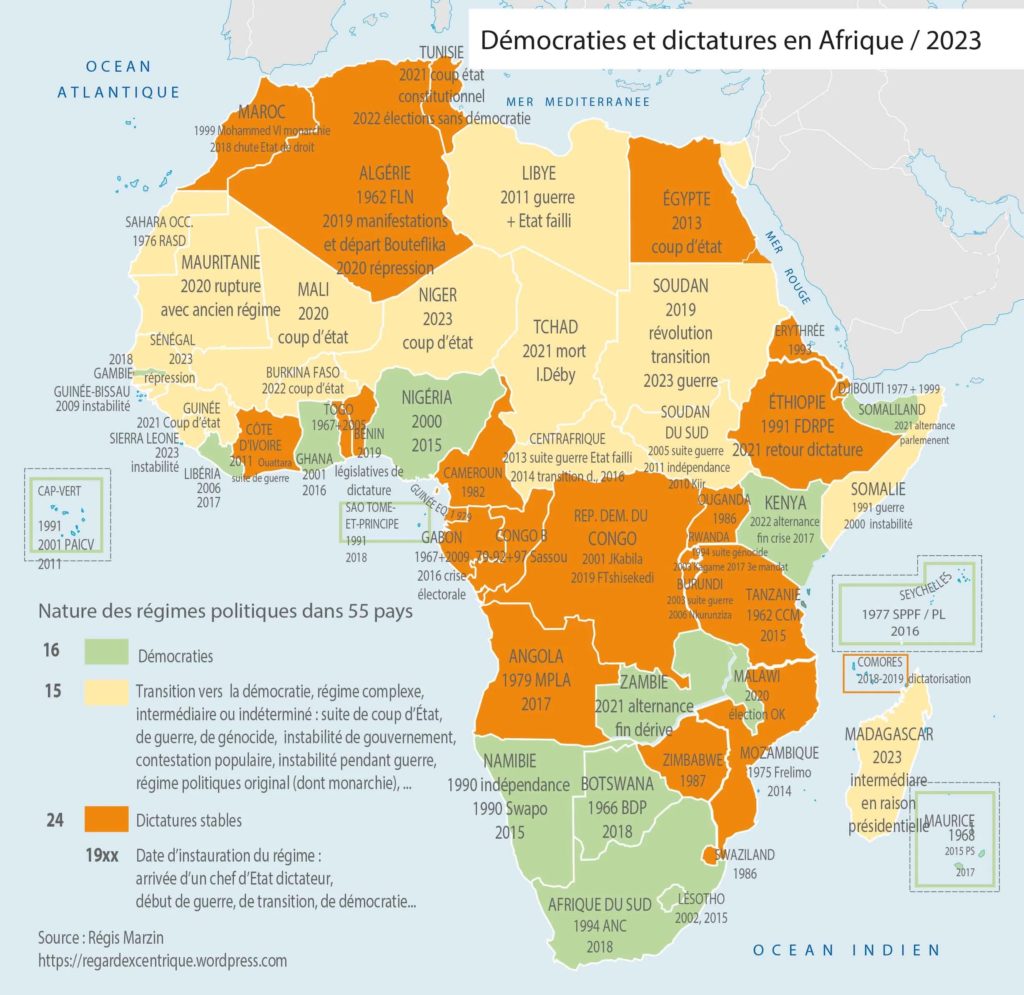

MAP | Democracies and Dictatures in Africa, 2023

Régis Marzin, “Démocraties, dictatures et élections en Afrique: bilan 2023 et perspectives 2024”, 31 janvier 2024, https://regardexcentrique.files.wordpress.com/.

FIGURE | Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa’s Share of Merchandise Trade in Global Trade

In: Regret Sunge, Nyasha B Kumbula and Biatrice S Makamba, “The Impact of Trade on Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Sources Matter?”, International Journal of Business, Economics and Management 8 (3):234-44. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.62.2021.83.234.244.

BOX | A Demographic Explosion in Figures

Around four centuries ago, African populations accounted for almost 17% of the world’s population. Between 1860, when it had approximately 200 million inhabitants, and 1930, sub-Saharan Africa lost a third of its population. In 1914, Africa’s population stood at 124 million, just over 7% of the world’s population, rising to 227 million by 1950. By 2015, Africa’s share of the world population had risen to 15%, with 1.2 billion inhabitants. Projections suggest that by 2050, Africa could account for 25% (2.5 billion) of the world’s population and by 2100 between 28% and 40% (Asia today represents 60%), totalling over 4 billion inhabitants.